We are leaving for Israel—for three months!—on May 5, for my husband’s sabbatical, and somehow I don’t think my Hebrew will be fluent by then. David’s Hebrew, after years of study and time in Israel, is pretty good. Me . . . well, I can definitely make my needs known, as long as my needs are to make it known that “the cat is under the table.”

Well, okay. It’s a little better than that. (I can also say, “The cat was under the table,” “The cat will be under the table,” and, “Blessed is the cat under the table, who created the fruit of the vine.”)

I learned to read Hebrew in religious school—the usual bat mitzvah stuff. I took a fun language class a few years ago at the JCC. And I had a wonderful modern Hebrew tutor, two hours a day, in Jerusalem the last two times David and I were there. I left the U.S. talking about cats and tables; I came back actually being able to chat.

And yet, even after a few months with a weekly tutor in Brooklyn, my Hebrew is still nowhere near where I’d like it to be. I envy David, and his friends and colleagues, the ease with which they make their way around scripture and menu alike.

Language means so much to me as—at very least—an entrée into a culture. Not a unique revelation, I realize, but for me, it runs deep. Without the fluent—if Valley Girl—Spanish I acquired on my first stay with my host family at age fourteen, I would not have such dear lifelong friends in Mexico. Without my crash course in Italian before a trip to Tuscany, my friend Judy and I would not have the same memories of long, Chianti-soaked nights with the locals. Without my passable Catalan, I would not feel so at home in Barcelona. And without Hebrew, in Israel I feel like a dork: I’m the lame American for whom everyone has to switch to English, the klutz in my husband’s crowd.

But my thing for language is about even more than having cultural currency to jingle in my pocket. I was born with it. My father, you see, is a famous linguist—specifically, a famous phonologist of Spanish, which means about seven people know who he is. (Still, as a professor emeritus at MIT, he is a heartbeat away from Noam Chomsky.) Much of his work is theoretical, unlike that of, say, ethnolinguists who head off into the bush with tape recorders, or people like Stephen Pinker whose books you can actually curl up with. My Dad’s definitive work offers a “systematic description of the stress contours of Spanish words that follows from morphological and markedness considerations” along with a formulation of “the Peripherality Condition,” which is not a Robert Ludlum novel. Still, his flawless Spanish is indistinguishable from that spoken by the natives, at least in Mexico, which is where it was acquired. (In Spain or Venezuela, everyone just assumes he’s Mexican.)

While his job does not sound glamorous, it does involve a lot of world travel. When I was a child we took extended trips to Catalonia and Venezuela, where he taught at summer institutes; we vacationed in Mexico with his colleagues there. And in my early thirties, I went with my parents to the Basque country. (As I said at the time, “I’d prefer to go with my husband, but I haven’t met him yet.”)

This trip went down as the most colossal linguistic failure in Harris family history. Never mind the fact that Basque has twelve grammatical cases (versus Latin’s cushy five); it’s linguistically unrelated to any other tongue. This means—as I learned when I cracked open the textbook Dad and I had each bought—that trying to learn it is like trying to stick Velcro to particle board. I’d do the exercises, biting my lip, and get them all wrong. The moment I’d finish, I’d forget everything. You don’t know how close I came to hurling the damn book off the subway. Me? Unable to learn a language? This was a soul-challenging, humbling, deeply frustrating first.

“Bet Dad can do this,” I thought. I emailed to find out. “How’s the Basque going?” His reply: “Fucking language from hell. This is a waste of my time.”

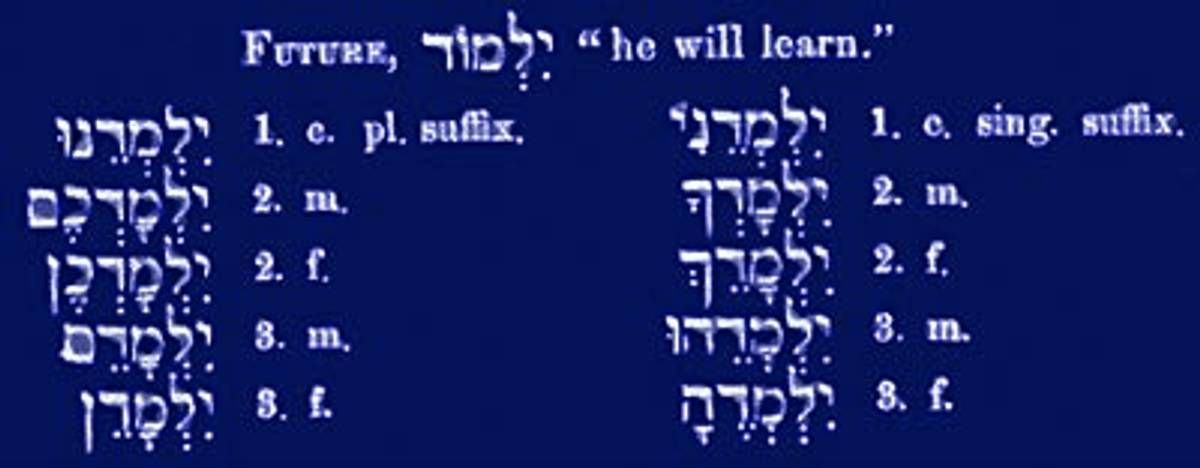

Hebrew, to be sure, is no Basque. But to be fair to myself, it’s not Spanish either. (Hence the song I made up when David took his crash course in Spanish: “Spanish Is So Much Easier Than Hebrew.”) What do the other languages I speak have in common? Shared Latin roots, for one—and, oh yeah, an alphabet. And to be able to say just about anything in Hebrew besides “chocolate” or “Golda Meir,” you have to make rote memorization a big part of your life. That, and this: If someone says, “Oh, Hebrew is so easy, it’s all so regular,” well, hu meshaker. (He is lying.) The other night I was practicing future tense with my tutor by discussing our trip to Israel. Our conversation went something like this:

Chantal: What will you be doing this summer?

Me: We [will travel] to Israel on May 5.

Chantal: [Correcting verb.] It’s irregular. What will you do there?

Me: I [will work] part-time.

Chantal: [Correcting verb.] It’s irregular. What will Bess do while you work?

Me: We [will find] a sitter.

Chantal: [Correcting verb.] It’s irregular. What will—

Me: I [will give up.]

There is much about Hebrew that is tidy and elegant, with great appeal for linguistic nerds and poets alike. You don’t need indefinite articles; you don’t have to learn the subjunctive. And, even when they’re tripping me up, I appreciate Hebrew’s complexities as well. You want a deliberately standardized language to have some messiness around the edges, like a homemade cookie. The standard, shrugging, in-joke reply to a student’s frustration: Kacha zeh b’ivrit. “That’s how it is in Hebrew.”

It makes me think of the old Yiddish song “Oyfn Pripitchik.” (I once took a Yiddish course too, by the way, at a local synagogue. Our textbook actually taught us to say things like, “It hurts everywhere.”) The first few verses of the song tell a sweet tale of students learning to read and write. Then the teacher speaks up: “When you get older, children, you will understand that this alphabet contains the tears and the weeping of our people.” I may shed tears over irregular verbs, but these are the irregular verbs of my people. Evkeh, aval lo evater. I will weep, but I will not give up.

Lynn Harris, a Tablet Magazine contributing editor, writes regularly for Salon, The New York Times, Glamour, and other publications. She is a co-founder of the website BreakupGirl.net.