Nancy Drew and the Case of the Politically Incorrect Children’s Books

The young sleuth’s early mysteries were racist and anti-Semitic. Can problematic vintage texts still be valuable for kids?

When I was 10, I loved the The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries on TV. My first seditious Jewish act was playing hooky from a Holocaust memorial service, pretending to be sick so I could stay home and watch a rerun (a rerun!) of an episode in which Shaun Cassidy’s shirt was unbuttoned.

But I turned up my nose at the Hardy Boys books. I was a Nancy Drew girl, all the way. In print, when not being played by the floppy-haired 1970s equivalent of One Direction, the Hardy Boys were boring as Weetabix. They were upright Boy Scouts, doing what boys were supposed to do. Nancy, on the other hand, was singular. If Harry Potter was The Boy Who Lived, Nancy was The Girl Who Dared. She was brave, rash, fierce. She had a snazzy car. She solved crimes that flummoxed the cops, snuck around in old abandoned houses, got locked in closets by bad guys … and she always kept her cool. Her mom had died when she was little, but her dad adored and trusted her and gave her free rein to save others. She was in charge, not her boyfriend, Ned Nickerson. She was beautiful, but she wasn’t an object. She was a doer.

Little did I know Nancy Drew had such a troubled past.

***

More than 200 million Nancy Drew books have been sold in the United States since their debut in 1930. Nancy has starred in numerous movies and updated reboots, graphic novels, and electronic games. Earlier this year, when Ruth Bader Ginsberg was asked who her heroes were, she said, “I suppose mine was Nancy Drew, because she was a girl who was out there doing her work and dominating her boyfriend.” (Back in 2010, she said more seriously, “I think that most girls who grew up when I did were very fond of the Nancy Drew series. Not because they were well-written—they weren’t—but because this was a girl who was an adventurer, who could think for herself, who was the dominant person in her relationship with her young boyfriend. So, the Nancy Drew series made girls feel good, that they could be achievers and they didn’t have to take a back seat or be wallflowers.”)

As author Melanie Rehak explains in her delightful history of Nancy, Girl Sleuth, Nancy was really the creation of two women: Harriet Adams and Mildred A. Wirt Benson. Adams was the daughter of Edward Stratemeyer, a publisher of dime novels who saw an opening in the market back in 1929 for a daring teenage girl detective. He wrote outlines for the first four books, which were farmed out to Benson, a journalist for the Toledo Blade. (Benson died in 2002, and her daughter and heir died earlier this year. Last week in Toledo there was an auction of Benson’s typewriters, awards, and the wooden desk upon which she wrote 23 of the first 30 Nancy Drew books. One of the typewriters went for $825, and the desk went for $525.)

Adams and her sister Edna took over running the syndicate after their father died, with Harriet increasingly doing the bulk of the editing. She was a proper wealthy lady, whose father wasn’t crazy about the idea of her employment, but Harriet loved Nancy and came to view her as her creation and even her daughter. Benson, on the other hand, was far less hoity-toity. She was a working girl from a grittier background, a former competitive diver, lifetime newspaper writer, and airplane pilot. (In 1970, when Benson was 65, she was still doing an aviation column for a Toledo paper called “Happy Landings.”) As Rehak puts it, “Nancy Drew was just a sideshow in Mildred’s life, unlike Harriet’s.”

Although they were mold-breakers in some ways, Adams and Benson, born in the 1890s, were also products of their time. And that meant the early books were rife with casual racism and prejudice. Nancy Drew criminals in the first books were almost invariably darker-complexioned and lower class. As independent Nancy Drew scholar Jennifer Fisher points out, facial features in the original Nancy Drew books were a surefire indicator of dastardliness: “A large or hooked nose,” “bushy or coarse stiff hair,” and “sallow skin” all indicated villainy.

Stereotypes abounded. In the 1930 version of The Secret of the Old Clock, there’s a lazy “Negro caretaker” with “a certain alcoholic glitter in his eyes” whose shirking of duty sets the stage for a robbery. When he realizes his employers’ house has been plundered on his watch, he asks Nancy, “Say, white, gu’l, you tell me wheah all dis heah fu’niture is at?” All his speech is in cringe-inducing dialect: “‘At’s right! Blame me! I ain’t s’posed to be no standin’ ahmy—I’s just a plain culled man with a wife and seven chillum a-dependin’ on me!”

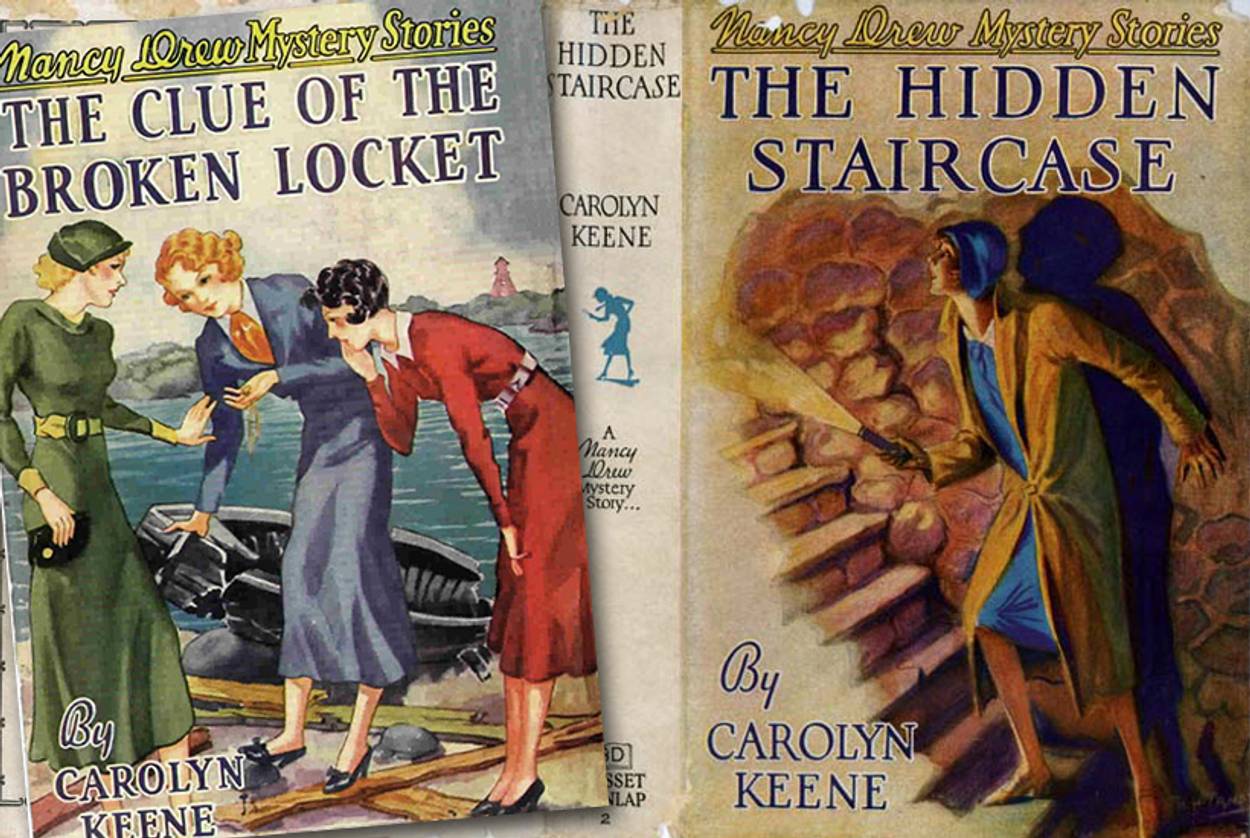

There were two early books with arguably negative depictions of Jews. One is The Hidden Staircase, whose villain, Nathan Gombet, is “miserly” and possessed of “shifty eyes” and a “hook nose.” Gombet (later changed to Gomber) was originally described in ways very much matching the stereotype of the Jew: “He was unusually tall and thin with spindling legs which gave the appearance of a towering scarecrow. The illusion was heightened by his clothing, which was ill-fitting and several seasons out of style. Nancy could not help but notice several grease spots on his coat. However, it was not the man’s clothing or miserly appearance which repulsed her, but rather his unpleasant face. He had sharp, piercing eyes which seemed to bore into her.” Gombet tries to swindle some nice old ladies out of their home (and kidnaps Nancy’s dad for good measure). Fortunately, Nancy foils his evil plans.

In The Clue of the Broken Locket, Nancy tangles with the Blairs, a tacky, self-absorbed, new-money couple who have changed their name from Sellerstein. They want to adopt two babies so they can make them go into showbiz and make a lot of money off them. According to one blogger’s entertaining synopsis, “Nancy does not like the Blairs because Kitty is overly rouged (read: whore) and Johnny is swarthy (read: criminal).” Also, the Blairs are slow to respond when the babies cry, because all they care about is ungapatchket clothing and going out and being fabulous. Nancy knows that the children will be better off with their real parents, so she figures out who they are and reunites them, and it’s all good. Which makes no sense, but Nancy knows best.

Starting in 1959, the books’ publisher put pressure on Adams to revise the books—not only to eliminate bias but also to modernize the language and streamline the plots. Adams was cranky about it, but she acceded. “Revising the books wasn’t just about removing stereotypes,” Fisher told me. “It was about shortening them to around 180 pages from around 210 pages. A lot of the descriptive elements got lost. Subplots were dropped. A lot of people feel that the spice was lost; the revising quickened everything and made the books choppier. The main reason they were revised was that they were cheaper to produce.” Some of the books were drastically rewritten—The Clue of the Broken Locket dumped the adoption plot entirely and became a story about a Civil War treasure hunt—and some were less drastically changed. The Negro caretaker in the first book became a white Southerner who says things like “I’m hornswaggled!”

Today you can buy both original and revised versions of the first 34 books. I grew up reading the revised versions, so to me, they’re canon. But I understand Rehak’s and Fisher’s love for the originals, with their quirkier plots, greater dangers, and more complex language. As Rehak said, “I grew up reading politically incorrect books, but I grew up to be a left-leaning, inclusive person.”

Lots of beloved classics are problematic. The Little House on the Prairie books contain multiple uses of the phrase “the only good Indian is a dead Indian.” (The original version also said, “There the wild animals wandered and fed as though they were in a pasture that stretched much farther than a man could see, and there were no people. Only Indians lived there.”) The original Oompa Loompas were black pygmies “from the very deepest, darkest part of African jungle” who were thrilled to be kidnapped into Wonka slavery. Dr. Dolittle, Oliver Twist, Babar … all have issues with racism, colonialism, or anti-Semitism. But as a parent, I think we can talk about troubling aspects of vintage books with our kids. I was horrified by an essay by a woman who took it upon herself to “childproof” Harry Potter as she read it aloud to her son, making it less scary and more respectful of authority, even changing the text so that Voldemort didn’t kill Harry’s parents. If you think your kid may be too young for a classic, wait. And consider discussing, rather than whitewashing, the aspects of the text that trouble you.

The original Nancy Drews came out of the Depression; they can be read as middle-class fantasy novels, fairy tales about fast cars and pretty outfits and a teenager who could make the world seem safe again. I read them not knowing that they’d once had such distressing portrayals of ethnic characters. But even knowing this now, I can’t turn against Nancy. She was dauntless and nervy, and those are qualities for today’s girls—of all backgrounds—to emulate.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Marjorie Ingall is a columnist for Tablet Magazine, and author of Mamaleh Knows Best: What Jewish Mothers Do to Raise Successful, Creative, Empathetic, Independent Children.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.