A Love Supreme

Today, the nation’s highest court affirmed same-sex marriage. For my family, and tens of thousands of others, it’s a cause for celebration.

Today, the Supreme Court affirmed same-sex marriage in this country. The word “dignity” appeared nine times in Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion, which concludes: “In a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death. It would misunderstand these men and women to say they disrespect the idea of marriage. Their plea is that they do respect it, respect it so deeply that they seek to find its fulfillment for themselves. Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions.”

Four Justices dissented vociferously. Scalia’s dissent was fiery (and quotable). He said of Kennedy’s writing, “the opinion’s showy profundities are often profoundly incoherent.” (Burn!) He sneered, “The Supreme Court of the United States has descended from the disciplined legal reasoning of John Marshall and Joseph Story to the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie.” He got snarky, asking, “Who ever thought that intimacy and spirituality [whatever that means] were freedoms? And if intimacy is, one would think Freedom of Intimacy is abridged rather than expanded by marriage. Ask the nearest hippie.” (On Twitter, NFL producer David Fucillo noted, in a nod to Tropic Thunder, “Scalia went full Internet commenter in his dissent. You never go full Internet commenter.” Twitter also reveled in celebratory GIFs of Neal Patrick Harris dancing joyfully with Elmo, doctored photos of the justices in glittering rainbow robes, and mockery of dimwitted young conservatives sighing that they were moving to Canada—where same-sex marriage has been legal since 2005.)

Thinking about today’s historic legal decision, I went back and looked at my dad’s breathless blog account of my brother Andy’s brit ahava (literally “covenant of love”) with his now-husband, Neal. Andy and Neal’s ceremony was on June 2, 2002 (22 Sivan 5762, for those playing along with the Hebrew calendar). It was another era. As Neal noted in their program booklet, “Although this brit ahava is meaningful to us spiritually, socially, and emotionally, it has no legal status. Except for Vermont, Hawaii, and California (and a few nations of the European Union), states do not legally recognize domestic partnership, let alone gay marriage.”

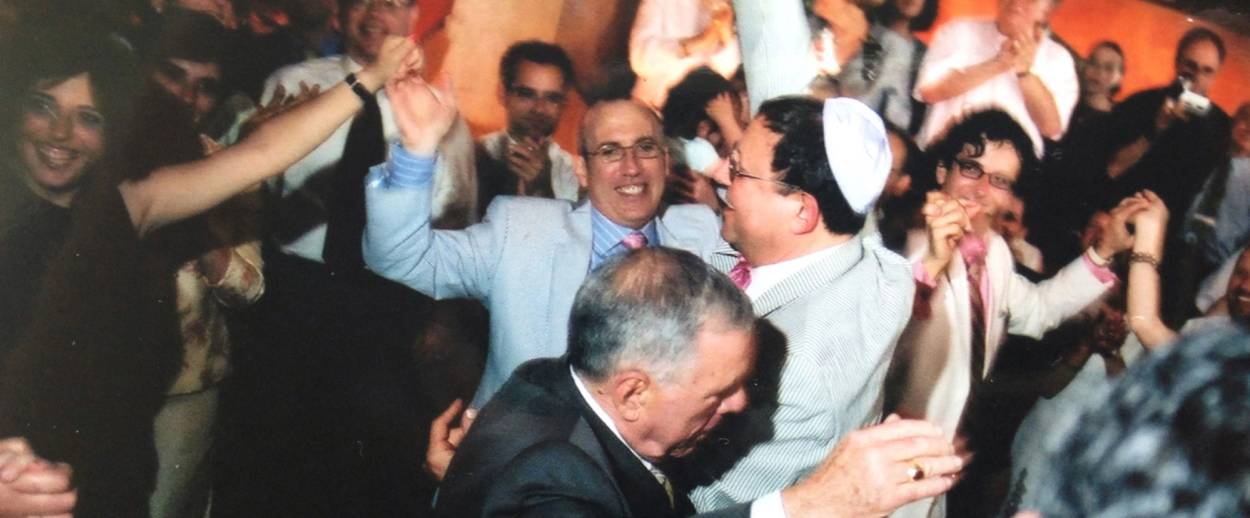

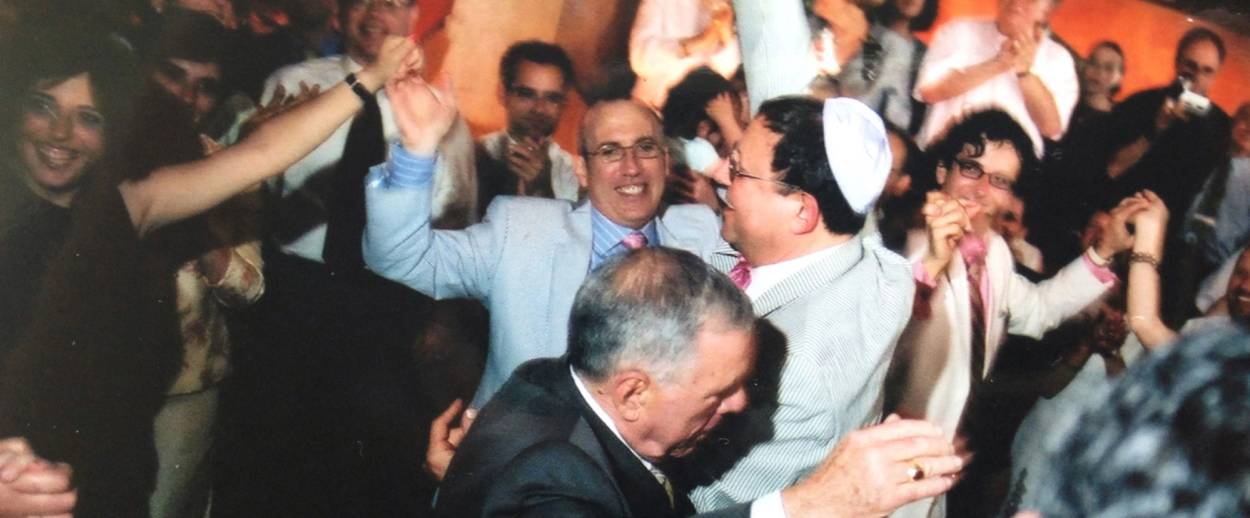

Even though Andy and Neal’s brit ahava had no legal standing, I revisit my dad’s exuberant account of the event and look at his pictures and remember what a beautiful day it was. The grooms wore seersucker suits. They glowed. There were lavender kippot stamped with “I had a gay old time at Andy & Neal’s brit ahava.” The chuppah was designed by Andy and Neal’s friend Ellen and sewn by my Aunt Gilda, with individual squares made by other family and friends, in the scarlet, purple, gold, and blue palette of the original aron ha’kodesh. Its corners were held up by four friends who’d helped Andy and Neal find their way to each other. (Which took a while. They met several times—at a benefit for Jews for Racial and Economic Justice, at a birthday party in Brooklyn, and at Kol Nidre services—before they began dating. To paraphrase John Green, they fell in love the way you fall asleep: gradually, then all at once.)

By the time they stood up before their families and community to commit to each other, they were all in. “Something changed in me when I fell in love with Neal,” Andy told me today. “I was over 30. I was ready. I was looking for someone to build a relationship and a family with.” I asked Neal if there was a single moment when he knew he was in love with Andy. “It was when we both realized we wanted to meet each other’s families,” he said thoughtfully (which is the way he says everything). “I realized I wanted Andy to meet my dad. I wanted to know his sister. It wasn’t a feeling of obligation—it was that I really, really wanted to know his family and have him know mine.” He laughed. “I told Andy, I don’t do divorce. I do death.”

They were grown-ups. They understood precisely what a lifetime commitment entailed. They’d written last wills and testaments, living wills, powers of attorney, health care proxies, rights to hospital visitation documents. (When one’s committed relationship has less legal standing than a Kardashian’s 72-day marriage, that’s only prudent.)

They thought hard about how to incorporate Jewish traditions into their ceremony at a time before the Conservative movement allowed its rabbis to officiate at LGBT weddings, before the Jewish Theological Seminary was willing to ordain LGBT Jews who wanted to become rabbis, before the New York Times published LGBT couples’ wedding announcements. They used the words “re’im ahuvim” (“beloved friends”) rather than “hatan v’kallah” (bride and groom). They each walked seven circles around the other. They both broke glasses—wrapped in a silk scarf that had belonged to Neal’s mother, Shirley, who was killed by a drunk driver when Neal was 22. Before Neal could finish becoming the wonderful man he became. Before he was fully out. Before he was a pediatrician. Before Andy.

Andy and Neal’s rabbi and friend Roderick Young officiated at The Brotherhood Synagogue, under the invitation of Brotherhood’s Rabbi Dan Alder. The fact that this rabbi was so welcoming of LGBT Jews who weren’t even members was one of the major factors that led to us joining this shul. When Josie became bat mitzvah at Brotherhood 13 years later, I thought back to my first time in the building, wearing chubby, snoozing baby Josie in a Bjorn on my chest. Decisions of all sorts—kindnesses, invitations, legal decisions—have far-reaching and unforeseen effects.

My dad’s joyful recollections are hard for me to read now. He died in 2004. I miss him. Though the pages are haphazardly organized (there was no blogging software then, no established information architecture for cumulative online narratives, and almost no one knew the word “blog”), Dad’s delight feels palpable, even in pixels, even today. “We met the Hoffmans in the dining room of the hotel for breakfast,” he wrote of his new in-laws. “Once again, it was like being with our own family. They were our own family. You know you’re with your own family when you can wipe your mouth with your hand if you dribble, and when you can burp at the table and not have to say, ‘Excuse me.’ ” At the pre-wedding party, he achieved his lifelong dream of singing “Sunrise, Sunset” at a family wedding. It was so hammy it broke every law of kashrut. Neal accompanied him on the piano.

***

Much has changed in the past 13 years. Dad is gone. My grandma, who proudly presided like the matriarch she was over the dinner for out-of-town guests, is gone, too. So is Neal’s beautiful niece Samantha, taken by cancer much, much too soon. But time brings gifts as well as losses. In the last 13 years, cousins have gotten married and had families. Jonathan and I had Maxine. And Andy and Neal have joined the estimated 40,000 gay male couples in America with children. (Demographer Gary Gates estimates that there are 120,000 lesbian couples raising kids.) Their daughter’s name is Shirley Michaela, and she is hilarious and exuberant, like my dad—a man she never met, a man she has no biological connection to, a man who would have adored her.

Since 2002, same-sex marriage has also become widely available. By this time yesterday, same-sex couples could marry in 36 states and the District of Columbia. And today, thanks to the Supreme Court ruling, gay marriage is legal everywhere.

Even though Andy and Neal had their brit ahava in 2002, they had a second ceremony in Massachusetts in 2008, where they were legally married. Why did they feel the need to get legally hitched after their gorgeous homemade ceremony? What difference does marriage make?

Andy told me today, “Both Neal and I grew up in traditional homes, with parents who loved and cared for each other. We wanted to replicate that. And it was important for Shirley to be able to tell others and hear from others that her parents were married.” My brother and brother-in-law expected the marriage to be pro forma, since they already considered themselves married in all but name. They were shocked at how moving they found their little private ceremony in Provincetown. “We got this Justice of the Peace who took her work very seriously, who said, ‘By the power vested in me by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and more importantly, by the power of your love for each other, I now pronounce you husband and husband.’ And the words just made us both tear up. And the fact that we had this baby flower girl with us singing the itsy-bitsy spider song … that made it so moving. It felt like we did this thing, and it was part of an incremental act of creating equality for everyone, and now we can move on to the rights of individuals, globally and locally, who lack civil rights and are hurting.”

George Eliot wrote, “What greater thing is there for two human souls, than to feel that they are joined for life—to strengthen each other in all labor, to rest on each other in all sorrow, to minister to each other in all pain, to be with each other in silent unspeakable memories at the moment of the last parting?” What greater thing, indeed? Scalia’s rage aside, why is this level of love and commitment less legitimate simply because the two human souls are of the same gender? Why do we not laugh out loud at the grasping-at-straws arguments by opponents of marriage equality that the ability to procreate should be a prerequisite for marriage? (If that were the case, my 74-year-old widowed mom’s recent remarriage to a 74-year-old widower should be null and void.) The belief in the rights of children to dignity and the knowledge that their parents’ relationships are legitimate may be what swayed Justice Kennedy toward gay rights. But birthing kids is not the be-all and end-all of marriage. Plenty of straight couples choose not to spawn. Plenty of straight couples who’d love to have kids can’t. (Put all the infertile women on an ice floe!) Kids are not the reason to make LGBT marriage legal, and kids are not a reason to make it illegal. (The “oh noes, think of the children!” rationale should be laid to rest by a huge study released Wednesday that looked at 19,000 studies and articles about same-sex parenting and found overwhelmingly that children raised by same-sex couples are no worse off than children raised by parents of the opposite sex.) And indeed, the majority opinion rejected the notion that marriage is all about having children: “This is not to say that the right to marry is less meaningful for those who do not or cannot have children,” Kennedy wrote. “An ability, desire, or promise to procreate is not and has not been a prerequisite for a valid marriage in any State.”

Like the Velveteen Rabbit, my brother’s and brother-in-law’s brit ahava was real to us. But their legal marriage is real to everyone. It is a huge thing for gay couples to be told they are no longer unequal citizens in this great country. There are still many battles to fight, many inequalities left to address, many losses we’ve faced and continue to face as a nation. But today feels like a celebration.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.