Is Going off Seamless the 21st-Century Version of Keeping Kosher?

A buggy new redesign led one ardent fan of the food-delivery app to grow more mindful of his relationship with his meals

On June 18, I ordered an omelet, a small salad, a wedge of feta cheese, some toast, black coffee, and two rugelach cookies for breakfast. For lunch, it was General Tso’s chicken with a side of pork fried rice and a ginger ale. Dinner found me in the mood for a large Greek salad, grilled chicken and vegetable kebabs, and a side of garlicky tzatziki, extra pita on the side.

I’m telling you this for three reasons. First, to suggest that I love to eat. Second, to prove that, regrettably, I do not obey any dietary restrictions, religious or otherwise. And third, because all three meals were procured using the popular food-ordering application Seamless, a service that I once dearly loved but am now determined, in an odd 21st-century take on keeping kosher, never to use again.

Some people wait to be incarcerated before they decide to look deep within themselves and repent. For others, it takes the passing of a parent or the loss of a job or some other Orphic moment. I’m of the generation for which a dead cell-phone battery counts as tragedy; all it took for me to search my soul was the redesign of the Seamless app.

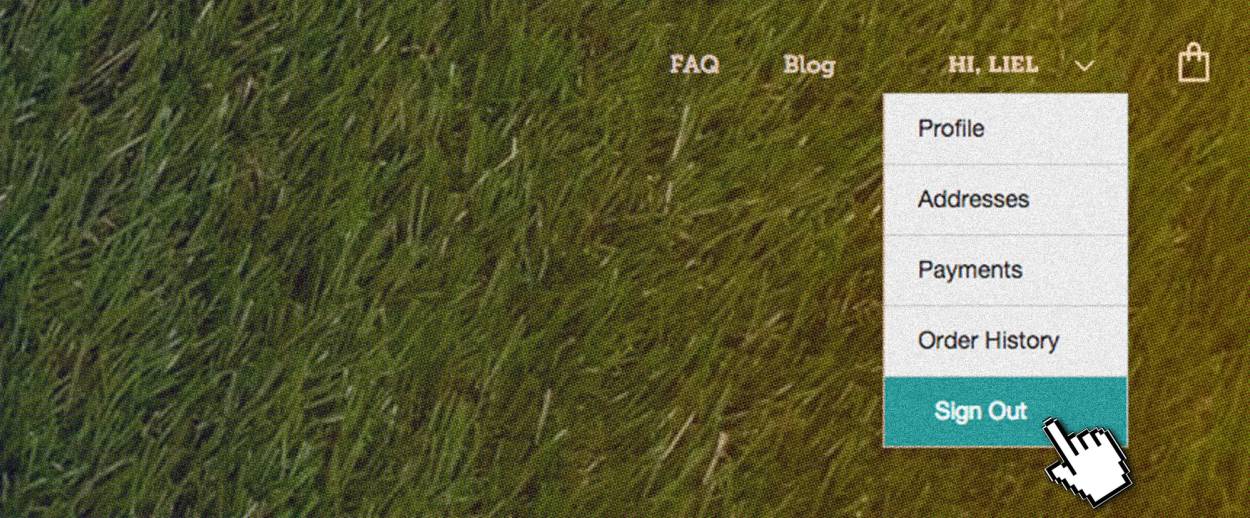

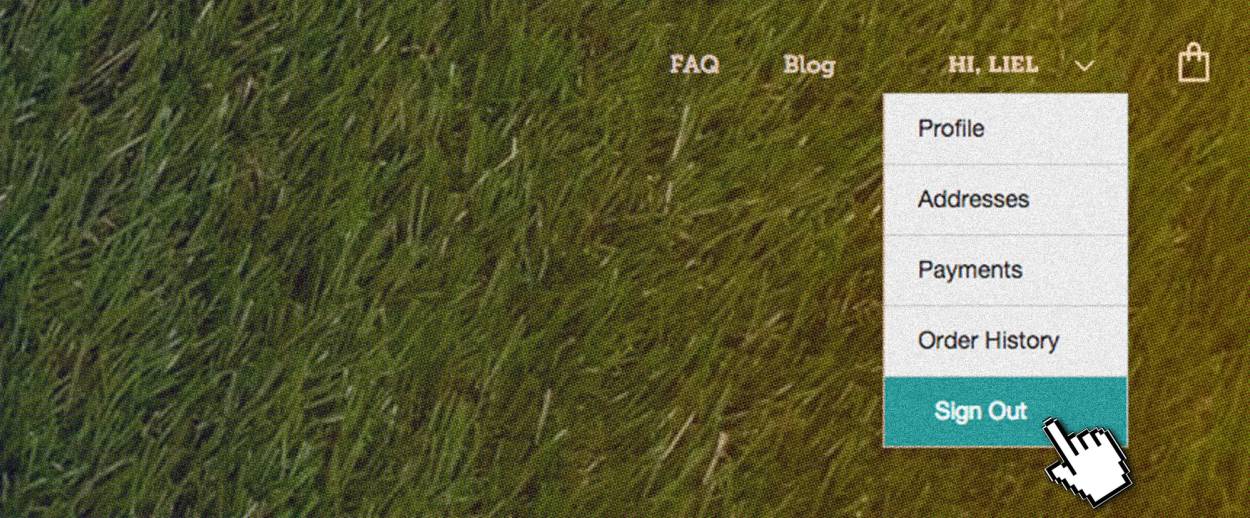

It crept up on me like a shark, agile and terrifying. I clicked the familiar red icon one morning and there it was, some sleek monstrosity, so different from the intuitive interface I had come to know and love. It felt like walking into your childhood home years after new tenants have made it their own and seeing that your most intimate landscapes had been painted over and stacked with strange new furniture. Instinctively, I rebooted the app. This, I murmured to no one in particular, had to be some kind of mistake.

It wasn’t. It was, the company promised me in a cheerful animated video, an effort to “refresh” the service, taking into account the comments and insights of users like me. Maybe users like me knew better, I thought. Maybe the new design will be good.

I made my food selection. The app crashed. I sighed. All this was normal. I know tech, realize that redesigns are necessary, understand that every tweak to the system is likely to generate a glitch or two. I breathed deeply. This, after all, was Seamless, the app I used more than any other, the magical portal that produced, with nothing more than a light tap, a torrent of tapas, a stream of sushi, iManna from the digital heavens. It deserved my patience. I launched the app again. Again, it crashed.

Thus began the long and dark night of my soul, not to mention my stomach. Attempts to get the app to work were futile. Attempts to get Seamless’ customer service representatives to deliver anything more than a few canned and insipid lines were more futile still. At first, I was polite, respectful, a deferential believer waiting for some authority to sweep in and dispel doubt. But the more the bugs persisted, the more I realized that I was losing my faith, not just in Seamless itself—the service, it is very likely, will respond to the catastrophic glitches and the public pillories they inspire by hiring some competent hands and fixing its array of disasters—but in what it represented.

Even when our union was strong, I harbored no illusions about Seamless’ appeal. The service was alluring because it was simple, because it eliminated the need to shuffle through crammed kitchen drawers looking for the right printed menu, because it did away with picking up the phone and shouting your order at some poor cashier working in a noisy room. It made the process of securing a speedily delivered meal mindlessly easy, and I loved it for this very reason.

I should’ve known better.

The scion of a long rabbinic dynasty, I am a few cheeseburgers removed from the faith of my fathers, but I have often pondered the laws of kashrut and their intricate beauty. You would think that the Torah, a book that does not hesitate to spend much time and energy on the precise course of action one ought to take should some irascible ox happen to go on a goring spree, would be more specific when it came to what its adherents could or couldn’t eat and why. Instead, in its wisdom, the Torah leaves us with nothing but complications to resolve.

One of the most elegant attempts at resolution to this particularly knotty question comes from Nehama Leibowitz. While many other faiths and traditions regulate their followers’ menus, she wrote, they frequently tend to explain their prohibitions by portraying the forbidden animal itself as inherently dirty. Judaism, Leibowitz argued, is different; Judaism holds no grudges against the pig or the mollusk itself. The beasts are not inherently evil. The responsibility for avoiding them is therefore placed squarely on us humans, a test of our ability to discipline ourselves and follow the will of the Divine even if we may not always understand its machinations.

The same demand for mindfulness and responsibility is everywhere present in the letter of the law. The animals slaughtered mustn’t suffer. They mustn’t have their limbs torn out while still alive, a common practice prior to the advent of refrigeration. The knife with which they are butchered must be so sharp as to ensure no pain would be felt. These are all sensible and earthly requirements, but the Torah goes further: In forbidding us to boil a kid in its mother’s milk, for example, or in insisting that we may consume an animal’s flesh but not its blood—the vessel, presumably, of the creature’s soul—the Torah makes sure we think before we bite, permitting us much but demanding that we exercise our dominion as carnivores with gentleness and care.

I’ve thought about all these considerations before. But it never occurred to me, amid the comfortably numbing ease of summoning my meals with a smartphone app, that the same spirit applied not only to what we eat but to how we obtained it as well. Kashrut was there to make me consider each step of the food production process, from pasture to plate; Seamless was there to help me forget about all but the chewing.

Would dropping Seamless make me a more mindful eater? A better person? I felt compelled to try. For the first time in four years, I picked up the phone and called the Chinese restaurant up the block.

The person on the other end of the line had trouble hearing me above the din of clanking forks and bussed plates. Her English was shaky. I had to speak loudly, slowly, and clearly. It was precisely the sort of experience I had once found to be such a nuisance and that drove me right into the ready arms of the app. But now I didn’t mind the conversation at all. The Chinese woman and I may not have been able to communicate like algorithms—quickly, efficiently, precisely—but we were capable of an even greater feat: We were communicating like human beings. Ours might’ve been flawed and drowned by noise, but it was a conversation nonetheless, an attempt at communion, no matter how brief, between two conscientious souls. My pork fried rice never tasted so good. It almost felt kosher.

It’s been a week now, and, barring a moment of weakness here and there, I’ve been good about my newfound resolution to go off Seamless. This has meant more conversations with men and women in restaurants, and more opportunities to contemplate their role in laboring to prepare my cheap and ready meals. It also meant more trips to the supermarket, an inconvenience I was previously happy to sacrifice to the gods of opportunity cost but that I now treated as a compelling ritual of my new faith. Like all those who’ve embarked on meaningful journeys of reinvention, I realize there’s much still to be done, and many thorny issues yet to address; if I bid farewell to Seamless, for example, why continue to use Uber, or TaskRabbit, or any of the other services I so dearly love but that rely on the same mindless convenience I’ve rejected when it comes to ordering my food?

I’ve no elegant answers. All I have is the convert’s joy of discovering a new way of being in the world, and the subtle but surprising pleasure of having to pick up the phone and speak to another living soul when ordering my lunch.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.