My Father’s Commandments

In public, he was a lawyer to the stars. But after my father died, I discovered that he’d privately yearned to be a Bible scholar.

My father abandoned organized religion on the day of his bar mitzvah. He ascended the bimah ready to chant his Torah portion and join the generations of thirteen-year-old Jewish males who had successfully negotiated this ritual passage to manhood. Alas, he had memorized the wrong portion.

Talmudically speaking, reading out of order is not an option. So, he never became a bar mitzvah. As an adult, he never joined a synagogue. As a parent, he never sent me to Hebrew school. As a result, I didn’t get invited to a lot of bar mitzvah parties.

Apart from a semester abroad as an exchange student in a Belgian convent during my senior year in high school—they called me La Juive—I remained biblically challenged until I took a course in the Gnostic Gospels with Elaine Pagels in college. She was not yet the rock star of biblical studies she has since become. I was shocked to learn that my father had read her book and knew her work well. It was my first intimation that the failed bar mitzvah boy had morphed into something of a biblical scholar. We talked about the Old Testament, too. He said: “The Ten Commandments are the basis for all Western jurisprudence”—a statement I took as gospel.

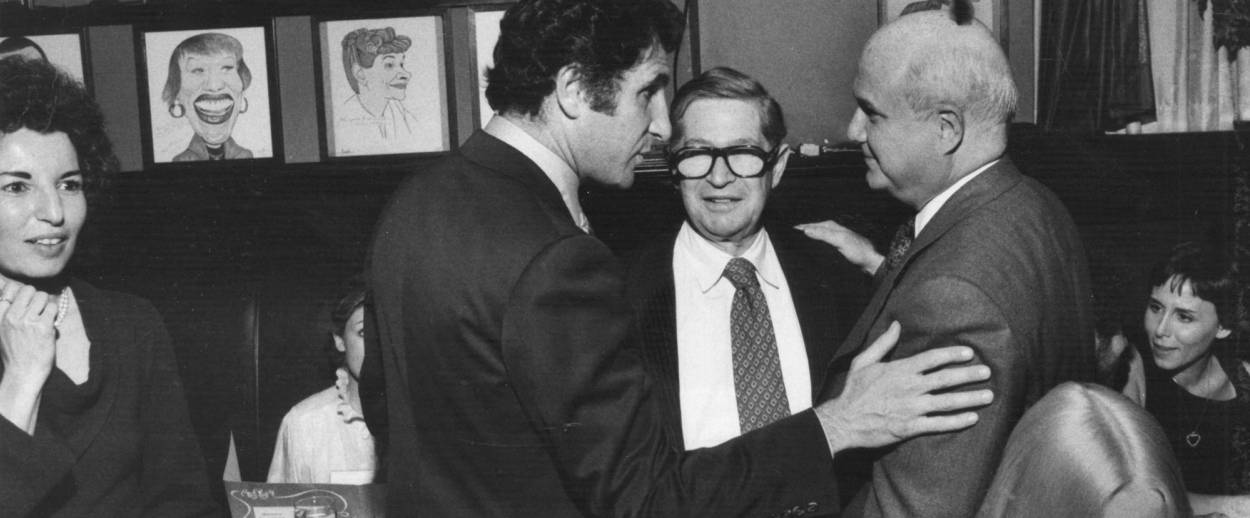

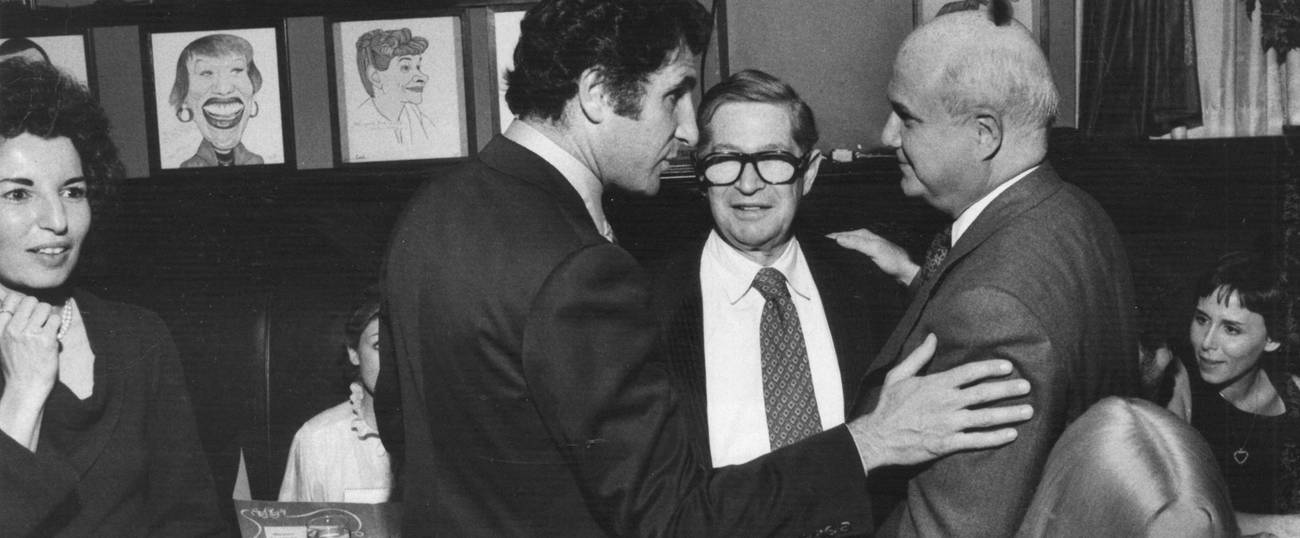

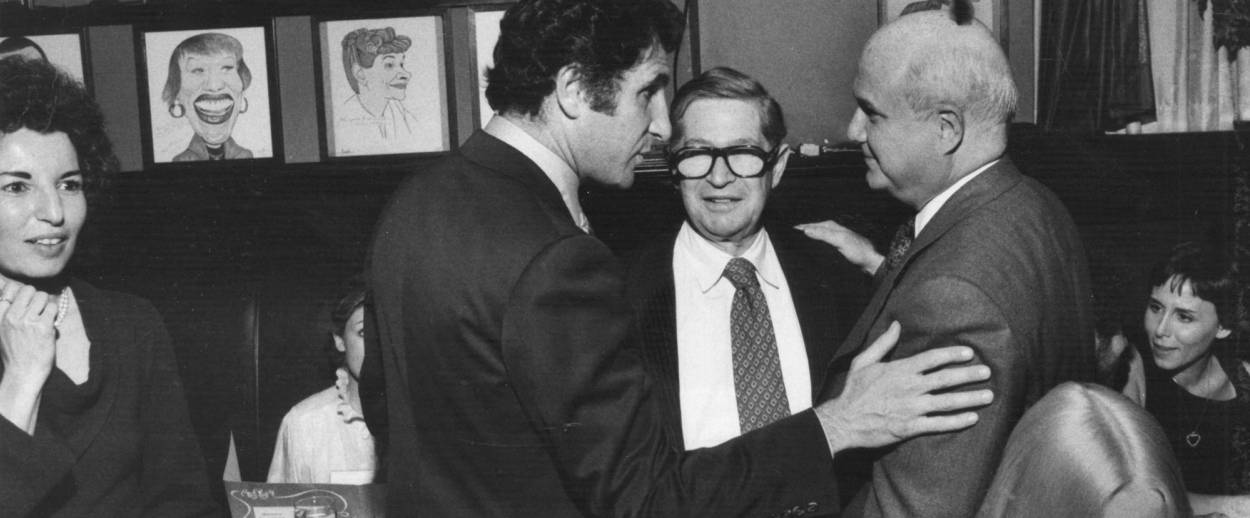

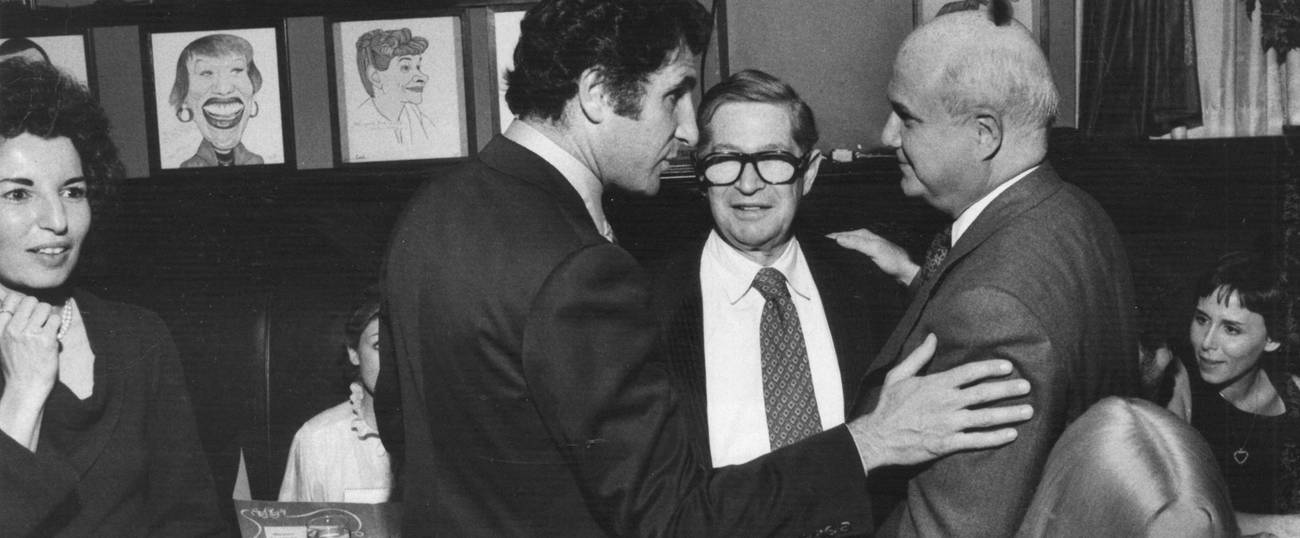

By day, he was Morton L. Leavy, Esquire, “Morty Baby” to his showbiz clientele—writers, directors, producers, lyricists, and actors who never wrote, directed, produced, limned, or appeared in a flop. His client list included everyone from Robert Graves to Meat Loaf to me. When you retained Mort Leavy, you got undivided attention and unequivocal, familial support. “You’ve done it again!” my mother declared more than once at opening night parties for shows that closed the next day.

The writers Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, whose representation meant most to my father, credited the longevity of their marriage in part to an inability to decide who would get Mort in a divorce.

Arthur P. Jacobs—ApJac Baby!—producer of the Planet of the Apes series and Doctor Dolittle, phoned every night just as we sat down to dinner even though we never ate at the same time twice and knew Morty Baby would always take his call.

My father was the son of a bookie and rumrunner named Abraham. As a towheaded toddler he served as his father’s decoy, stationed on the rumble seat of the Model T as the hooch-laden car sailed through customs at the Canadian border. He was the prettiest baby in an Asbury Park, New Jersey, parade and the youngest man to graduate in the class of 1934 from City College in New York. “At 18 He Heads CCNY Class Of 2,000 at Commencement,” a headline in a New York broadsheet declared. “He wants to be a lawyer and has intentions of entering Harvard in the fall.”

He went to Columbia Law instead and got a part-time job working as a magician’s assistant for a Broadway revue called Continental Varieties. His job was to translate audience requests for a Belgian Svengali who swore he could turn water into anything potable. One night someone demanded sauerkraut juice and my father couldn’t think of the word. The next day they made him stage manager. In that capacity he was tasked with presenting a bouquet of long-stemmed roses to the French chanteuse Lucienne Boyer, who closed the show every night with “Prenez Mes Roses.” First day on the job my father forgot to remove the thorns. She clutched the bouquet to her breast and screamed.

That was the end of life in the floodlights and the beginning of compassion. He would make his career in entertainment law, looking after the legal rights and fragile psyches of artists.

He practiced law parallel to the ground in a gray leather Herman Miller chair, whose springs had long since lost the battle with his girth. His round mound of renown rose above his Herman Miller desk like the Rockies emerging out of the plains. Entering his office, you heard a patriarchal rumble emanating from somewhere beneath the horizon of the cluttered desk. Phone ducked beneath his chin, hands gesticulating with either-ors, he perfected the art of the schmooze in the service of attaining the best possible deal. Done: he popped up, a beaming Jewish jack-in-the-box in a Turnbull & Asser shirt. “How ya doin’, baby?”

John Gregory Dunne testified to his bona fides in an August 1983 Esquire essay called “Big Deal,” detailing the particulars of a failed motion picture deal for John le Carré’s book The Little Drummer Girl, in which my father represented all the principals, including the author; the director, George Roy Hill; and the prospective screenwriters Didion and Dunne: “It is not all that unusual a situation. There are only a handful of good entertainment/literary lawyers, and they are constantly balancing the conflicting concerns of clients who work with each other, who wish to work with each other, who detest each other, sue each other, marry and divorce each other.”

Or, as my friend Dan Okrent, creator of the off-Broadway hit Old Jews Telling Jokes puts it: “No conflict, no interest.”

Dunne continued:

Morton Leavy is short, round, and benign; he looks, as I have often told him in the fifteen years he has been our attorney, like a Jewish Dr. Doolittle. He is so scrupulous that my wife and I once felt free to leave the country when he agreed to referee a negotiation she was having with her publisher and one I was having with my publisher. The twin negotiations—each for a new novel—needed a referee because my publisher is married to my wife’s publisher, a situation further complicated by the competitive strains between my literary agent and my wife’s literary agent, each of whom wished to negotiate a better deal than the other. I might add here that Morton Leavy was most aware of these strains as he is also the attorney for both my literary agent and my wife’s literary agent. We told him to keep the peace between the two of them, that we did not wish to be played off against each other, but that we also wanted the best deals possible.

Morton Leavy’s success as a referee was such that the only real difference between my contract and my wife’s contract was that she would receive fifty more free copies of her book when it was published than I would when mine was. Both my publisher and my wife’s publisher called Morton Leavy a son of a bitch, which he took as praise for a job well done.

I can’t remember which client gave him the pair of brass balls that sat proudly on his desk, but they now sit on mine.

Though largely deaf and mostly blind, he continued to practice law until his death at age eighty-seven in 2003, two weeks after breaking his hip while getting up from the table where Arthur P. Jacobs had interrupted so many dinners. When the paramedics arrived to take him to the hospital, he was lying on the brick floor dictating the particulars of a contract.

***

After his death, I inherited the contents of his library. The client collection, lovingly arranged in alphabetical order with unanimous inscriptions of praise, diverted me from grief. The big names and bright lights had always been more interesting than the hundreds and hundreds of volumes devoted to biblical law and archaeology, which had come to occupy more and more space in the den without my noticing. In the breadth of this collection, I first discovered the extent of his passion for the subject and how little I knew about that part of my father’s life.

I had never talked to him about the conferences he attended and addressed. I had never read the papers he wrote and delivered. I never learned what Torah portion he should have memorized. I never asked him to elaborate on the Ten Commandments.

I kept the most precious volumes, among them a 1902 edition of A Dictionary of the Bible, a set of four vellum-bound, gold-embossed books with hand-painted endpapers made to look like a peacock’s feathers—blue, green, and mauve. I donated the rest of his books to my synagogue and promised myself that one day I would delve into the legal files he had crammed full of notes and marginalia.

A decade passed. The vellum binding cracked and split. The books on the shelf in my living room that I dedicated to my father’s collection remained undisturbed.

With the invitation to contribute to this volume came an opportunity, finally, belatedly, to honor my father.

“Sure, I’ll do it,” I said.

I would dig through his notes and his papers and find in his blocky, angular masculine hand the part of him I had ignored. I would be my dad’s archaeologist.

Two months of digging through the attic, the basement, and the climate-controlled storage unit where I keep my children’s baby clothes produced only disappointment and the unhappy reminder that memory is unreliable. I had kept none of his papers.

I turned to the Internet. A month of online sleuthing produced only a citation for a 1985 paper he had delivered to the annual meeting of the Biblical Law section of the Society of Biblical Literature, added in 2013 to Brigham Young University’s database: “Customary Law in Biblical Narrative: Genesis.”

Neither BYU nor the Society for Biblical Literature could locate the paper. My dad preceded the digital age. The best they could do was provide an abstract, in which he argued that in biblical narratives, specifically the trials and tribulations of the patriarchs, you find the rudiments of common law: rules governing transactions between people as opposed to the covenant between God and his people.

I ransacked his books, looking for evidence of his exegesis. I found it scribbled in the margins of his edition of E. A. Speiser’s translation of Genesis. Specifically: Genesis 23. He had dissected the chapter, diagramming in the endpapers examples of common law he had found throughout the book. Among them: personal vengeance, human sacrifice, homicide, slavery, status of the sojourner, witnessing, covenant, sale of real property, divorce, adoption, inheritance, birthright, and polygamy, all of which except, I think, the last he dealt with in his practice.

The chapter concerns the death of Sarah and Abraham’s purchase of a burial site for Judaism’s matriarch. As Torah portions go, this is a major anticlimax, coming as it does immediately after the “Ordeal of Isaac,” a biblical showstopper in which God demands that Abraham sacrifice his only-born son. How many Yom Kippur sermons have been devoted to that harsh test of faith?

After the harrowing narrative of father and son, the boy carrying the wood for his own immolation to God’s appointed destination, the father tying up the son and laying him on the altar above the wood he had carried, the poised knife, the intervening angels, Chapter 23 is dry kindling. But, in it, my father found meaning not just in the evolution of jurisprudence but also in his own legal practice.

Sarah gets short shrift in Chapter 23. Her death at age 127 merits one paragraph. Mourning and bewailing are confined to two short sentences: the extent of it must be taken on faith. The rest is a negotiation between Abraham—“a stranger and sojourner”—and the children of Heth for a burial place for Sarah.

You have to consult commentaries and apocrypha, Louis Ginzberg’s Legends of the Jews, to get the whole story: how Satan tricked Sarah into thinking that Abraham went through with the sacrifice of Isaac and then acknowledged the falsehood, causing her to drop dead with joy. How Jewish.

In Ginzberg’s account, “a great and heavy mourning” ensued. Abraham had “great reason to mourn for even in her old age Sarah had retained the beauty of her youth and the innocence of her childhood.”

The biblical account also omits salient details about the burial plot Abraham sought for her in Hebron in the land of Canaan. The Cave of Machpelah was also the final resting place of Adam and Eve, chosen by Adam—no innocent—because he feared his body might be used for idolatrous purposes. God assuaged his fears by stationing angels at the entrance to deter trespassers.

This was not what interested my father. He focused on the polite give-and-take between the parties, strikingly modern in the niceties that camouflaged the bottom line. When Abraham, a resident alien lacking the right to purchase property, first asks for a place to bury his wife, the natives offer him any parcel he wishes. Abraham declines, asking to them to bring forth Ephron, “newly made the chief of the children of Heth,” who also happens to own the Cave of Machpelah and the field it lies in. No fool, Ephron offers to gift Abraham the cave but insists that he must take the field as well, which some commentators read as a shrewd move to avoid having to pay taxes on the whole tract.

Ephron makes the grand gesture, knowing full well that it is a deal Abraham cannot accept, thus freeing him to ask his full and exorbitant price—four hundred shekels of silver. “What is that between you and me?” he asks the patriarch.

Though God had already pledged the Promised Land to Abraham and his seed, it is not yet theirs. He needs clear title, and he needs witnesses to the deal, essential in a world where nothing was written on paper and codes of law had yet to be established. That, some scholars believe, explains the presence of legal transactions in biblical narratives such as Genesis 23. Locating the particulars in an oral tradition vouchsafed that precedents would be established, acknowledged, and accepted. Abraham counts out the silver at the current merchants’ rate.

It figures that my dad would focus on a passage that features the patriarch in the art of negotiation because that was his art, too. In the study of biblical law, he found a portion of the Torah that made sense to his logical, lawyerly mind, and assuaged a sense of intellectual inferiority he once confessed over dinner. To find the meaning of Chapter 23 was to find meaning in his career.

***

Yes, he went to the opening night of Hair in New York, Paris, London, and Budapest—or was it Prague? Yes, John Gielgud came to dinner and politely ate the My-T-Fine chocolate pudding I, at age five, prepared for dessert. Yes, John le Carré camped out on the trundle bed in our guest room between books and marriages.

But my father harbored a desire to be taken more seriously as an attorney or at least to be seen toiling in Serious Law, to engage in the rigors of legal debate as practiced at the highest levels and argued in the highest courts. That was not an option for a nice Jewish boy getting out of Columbia Law in 1937. He envied the practice of my former husband, who dealt with “matters,” not people.

I think I know how he felt. The desire to be deemed capable of more than the froth of sportswriting is one reason I welcomed this assignment.

But, absent my father’s guidance and scholarship, I floundered. I doubted. Seized by a crisis of faith, I called Elaine Pagels for counsel. She gently reminded me that the Old Testament is not her area of expertise.

Just as I resolved to abandon the task, I heard my father’s voice, as if from above, taut, not quite righteous, but brooking no nonsense. “Writers write.”

That was the advice he offered every whiny author, including me, who called to complain of writer’s block. My father’s commandment was an injunction as well as a statement of fact. After all: In the beginning was the word.

Excerpted from The Good Book: Writers Reflect on Favorite Bible Passages, edited by Andrew Blauner, © 2015 by Simon & Schuster.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jane Leavy, author of the New York Times best-sellers Sandy Koufax, A Lefty’s Legacy and The Last Boy, Mickey Mantle and the End of America’s Childhood, is currently working on The Big Fella: Babe Ruth and the Advent of Celebrity, to be published by HarperCollins.