The Wisdom of Peanuts

How Abraham J. Twerski—rabbi, psychiatrist, and author of more than 70 books—found inspiration in a popular comic strip

In 1999, when I was a freshman at YULA Boys High School, in Los Angeles, Abraham J. Twerski—rabbi, psychiatrist, scion of several rabbinic lines, author of dozens of books, authority on matters from Hasidism to drug addiction—came to speak to us and our parents about the dangers of substance abuse. I understood that he was a great scholar, and I remember being enamored of a person who dressed and looked like a Hasidic rebbe but spoke perfect English. But even more exciting, later that year I discovered that he was something of an authority on another subject: Charlie Brown.

In the school’s beit medrash, I stumbled across a small 1988 book titled When Do the Good Things Start? with a picture of Charlie Brown on the cover, and the author listed as “Abraham J. Twerski, M.D.” It was a remarkable moment: Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts comic strip had permeated the American scene to such an extent that it had even made its way into the beit medrash.

Now that Charlie Brown is back—with The Peanuts Movie scheduled for release on Nov. 6, a little more than 65 years after the strip first premiered in nine newspapers on Oct. 2, 1950—I called Twerski, who currently resides in Teaneck, New Jersey, to ask him about his connection with the comic strip and the surprising friendship he formed with Schulz.

***

On his father’s side, Twerski is a direct descendant of the famed Menachem Nachum of Chernobyl, author of the Meor Einayim and a prized disciple of the Maggid of Mezeritch; Twerski’s mother’s maiden name was Halberstam, another family of Hasidic royalty, and she was the daughter of the Bobover Rebbe, Rabbi Ben Zion Halberstam, who was martyred in the Holocaust. Twerski’s father, Rabbi Jacob Israel Twerski of Milwaukee, was the Hornsteipler Rebbe, a position currently held by Twerski’s younger brother Michel, who continues the family’s legacy in the West Side of Milwaukee. Twerski’s cousins are a who’s-who of Hasidism; he is related to the Rebbes of Bobov, Karlin, Klausenberg, Talner, and Skver. In short, Twerski has a priceless lineage. So, it’s no surprise that many of Twerski’s books—such as Rebbes and Chassidim , The Zeide Reb Motele, and Four Chassidic Masters —touch on matters relating to Hasidism.

In addition, Twerski wears another hat—literally and figuratively: that of a psychiatrist. While serving as assistant rabbi in his father’s congregation in Milwaukee in the 1950s, Twerski attended medical school at Marquette University. After finishing his residency, Twerski spent the next 20 years serving as the clinical director of the department of psychiatry at St. Francis Hospital, while also serving on the faculty at the University of Pittsburgh. He is a world-renowned drug and alcohol addiction expert, and in 1972 he founded the Gateway Rehabilitation Center in Pittsburgh. Twerski was also one of the first communal leaders to confront the issue of spousal abuse in the Jewish community, in his groundbreaking 1996 book The Shame Borne in Silence.

Twerski, who recently turned 85, is continuing to lecture and write at an aggressive pace. He has become a guru of sorts, writing books on matters of self-help and psychological well-being for Jews and non-Jews alike, such as Successful Relationships at Home, at Work and With Friends and Ten Steps To Being Your Best.

But where does Charlie Brown fit in?

Twerski explained to me that he was attracted to comic strips (or as he termed them, “the funnies”) as a child growing up in Milwaukee in the 1930s and ’40s, taking a particular interest in the Katzenjammer Kids, Popeye, and Henry. He said he found these strips to be “silly entertainment” and enjoyed reading them in the daily paper and in comic books. Years later, while working as a psychiatrist, he began to keep volumes of light literature, including books of the Peanuts strip, at his desk in order to reduce stress and to help him refrain from reading work-related materials during meals. At the time, he had a patient who constantly had relapses of alcoholism but was unable to admit that he was an alcoholic, as he always had an explanation by which he felt he could control his drinking. Twerski showed the patient a strip that showed Charlie Brown repeatedly trying to kick a football that Lucy held down; time and time again Charlie Brown failed to kick the football, yet he always rationalized why things would be different this time. The patient immediately connected with Charlie Brown’s failure to objectively understand the situation and admit his limitations. Twerski told me that he then realized that “Peanuts was more than just entertainment and that it could be used to convey messages much more effectively.” He began to collect Peanuts strips that had educational lessons in them, and in the late ’70s he began displaying them on a bulletin board titled “Post-Graduate Education” at St. Francis Hospital.

After years of collecting various educational strips, Twerski received permission from the United Feature Syndicate, Inc., the owner (at the time) of the rights to Peanuts, to use many of them in a book that contained Twerski’s analysis. When Do the Good Things Start? focuses on providing a guide to assist the reader with overcoming low self-esteem, building confidence, dealing with guilt, and dispelling loneliness. Twerski has written at length about the issue of self-esteem in his many books—even noting that almost everything he writes “relates in one way or another to the theme of self-esteem,” as he describes in a powerful 2008 essay, “My Own Struggle With Low Self-Esteem,” based on his longer video lecture of the same title. It thus comes as no surprise that many of his insights into the Peanuts comic strip touch on the issue of self-esteem.

Twerski then followed up with more books based on Peanuts: Waking Up Just in Time, which uses the twelve-step approach to treat life’s ups and downs; I Didn’t Ask To Be in This Family, on sibling relationships; and finally, That’s Not a Fault… It’s a Character Trait, which aims to provide the reader with a guide to a happy life and a manageable self-image. Interestingly, a fifth book, What’s the Big Deal?, was translated and published in Japanese, even though it has yet to be published in English.

When we met in person recently, I brought along my copy of When Do the Good Things Start? to be autographed. When I asked about his favorite Peanuts characters, Twerski began to flip through the book and point out the various personalities that Schulz had brilliantly created. “Lucy’s grandiosity is her defense for her low self-esteem,” Twerski said. “Charlie Brown feels terribly inadequate about himself,” he added. “Snoopy lives in the world of fantasy,” he noted. And he called the relationship between Schroeder and Lucy the “ultimate example of unrequited love.” Each time Twerski would find a comic strip, he would point to it and have me read it, and he would then proceed to explain the various deficiencies of the respective characters. Twerski also described the tremendous insights into addiction in particular in the countless number of strips that focus on Linus and his security blanket. Just as he had used Peanuts to teach messages to his countless numbers of patients, residents, and later his readers, Twerski was masterfully conveying to me the valuable lessons found in the comic strips.

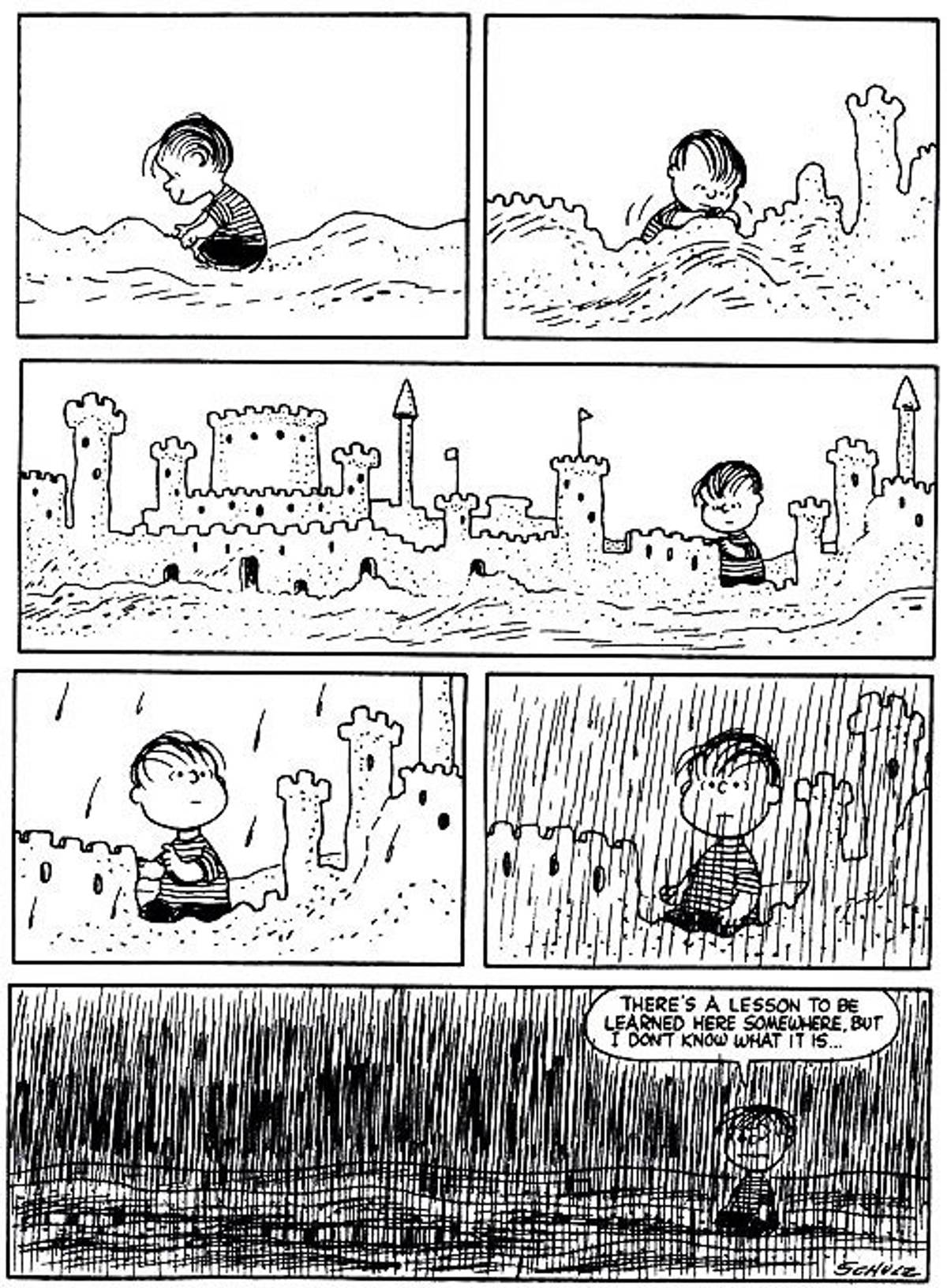

After the first book appeared, Twerski met Schulz for the first time and a lasting friendship between the artist and the rabbi began. The first meeting took place in a hotel lobby near Schulz’s home in Santa Rosa, California. “I was not starstruck at all,” Twerski told me. “Schulz was a very down to earth and humble person.” During the meeting, Schulz asked Twerski if he could pose a theological question, a proposal that Twerski, of course, acquiesced to. Schulz proceeded to ask Twerski for his thoughts on theodicy, the question of “why do good things happen to bad people?” Twerski responded by noting that this question has its roots in the Bible, and even Moses asked and failed to receive an answer to this question. Remarkably, Twerski told Schulz that one response he has to the question of theodicy is in fact found in a Peanuts strip. When Schulz asked which strip, Twerski responded by reminding Schulz of a Peanuts strip from 1959: In it, Linus is seen laboring to build a very intricate sand castle. Suddenly, it begins to drizzle and before long, the sand castle is wiped away by the torrential rain. Linus then says to himself: “There’s a lesson to be learned here somewhere, but I don’t know what it is … ” Twerski, despite being well-versed in matters of Jewish theology, admitted that he found Linus’ statement to be a profound response to the age-old question.

Over the course of the next few years, Twerski would occasionally reach out to Schulz through phone calls, and they met three additional times. Their fourth and final meeting together took place only two days before Schulz’s death in 2000. Twerski was in Northern California for another speaking engagement, and he visited Schulz at his home in Santa Rosa. Schulz had recently retired from the comic strip and had a stroke, and was suffering from colon cancer. Twerski remembers the meeting as being “incredibly difficult.” He told me: “Schulz was clearly in tremendous pain and due to the stroke, was having trouble searching for the right words to use.” As described in Twerski’s 2013 book about his years at St. Francis Hospital, The Rabbi and the Nuns, Schulz remarked to Twerski during the emotional meeting: “If I were to see in my cartoons what you see in them, it would paralyze me and I would not be able to draw.”

In his introduction to When Do the Good Things Start? Twerski questioned his own interpretation of Schulz’s strip: “Are my interpretations valid? Are they what Schulz had in mind when he created the strips? I don’t know, nor does it really matter. Reams of essays have been written about the characters in Hamlet. Did Shakespeare consciously intend all the meanings others have read into his characters? Again, the question is irrelevant. The characters speak in many different ways to different people. An artist creates with the intuition that inspires him.”

Schulz seemed to allude to this very point in his final meeting with Twerski. Schulz confided that of course, not every perspective that Twerski describes was initially contemplated by Schulz, yet he understood the value in allowing interpretations of his work to be published, and he very much appreciated their friendship. Twerski notes that when he departed from Schulz, Schulz remarked, “I want you to know that I value having you as a friend.”

To this day, Twerski says he has a tremendous amount of respect for Schulz and appreciates the countless lessons that he learned from Peanuts. In 2013, he was a featured speaker at Jewish Recovery Center Retreat & Shabbaton, an annual event for Jewish addicts in recovery and their families. After being asked why he was wearing a Snoopy tie, Twerski noted that he was not aware of any American psychologist who had the “intuitive psychological knowledge” that Schulz had. Indeed, Twerski often wears Peanuts ties as a tribute to Schulz and continues to draw upon the cartoonist’s wisdom in his lectures and books. As Rabbi Nosson Scherman, the general editor of ArtScroll—which has published dozens of Twerski’s books—told me: “I doubt that there is anything like his treatment of Peanuts. Charlie Brown is one of the greatest thinkers of modern times, and it took Rabbi Twerski to bring his profundity to public notice.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Aaron R. Katz is an associate in the corporate and securities practice at Greenberg Traurig. He lives with his wife and three children in Israel.