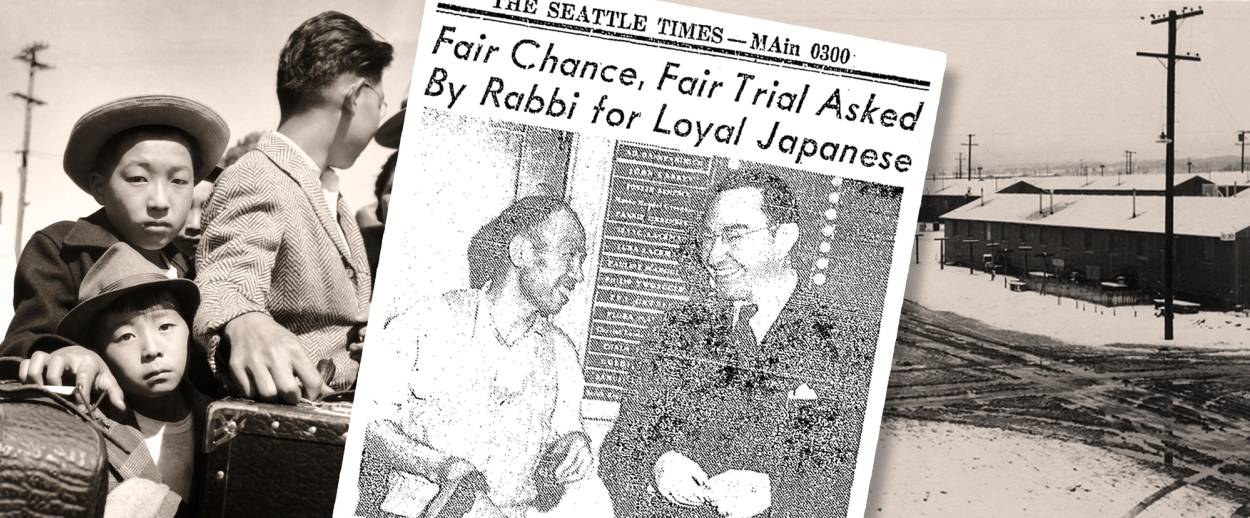

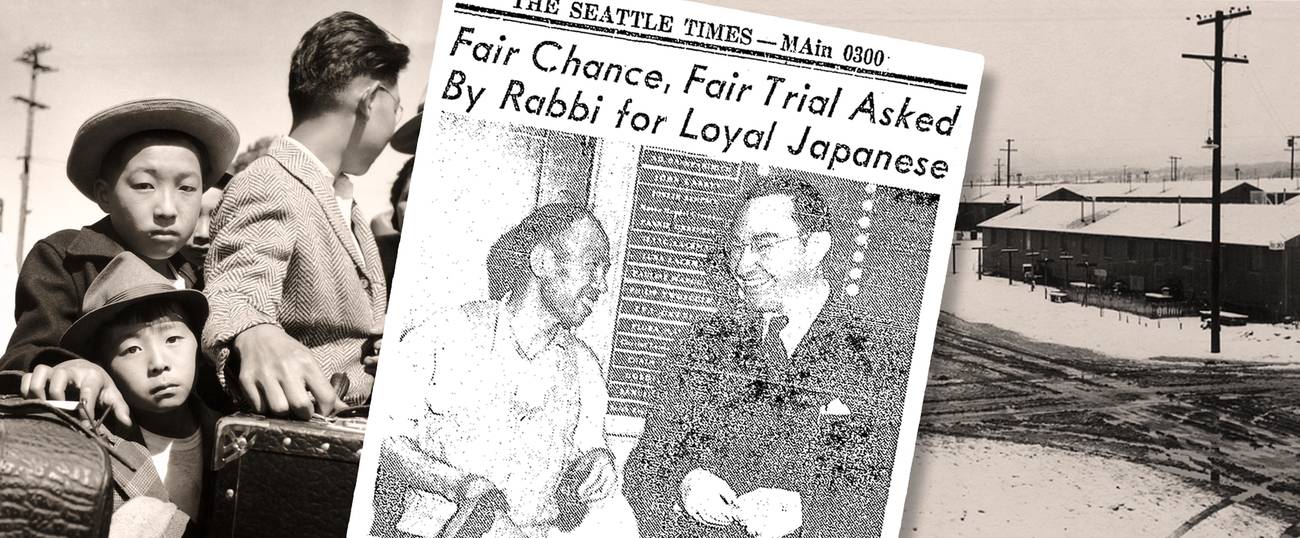

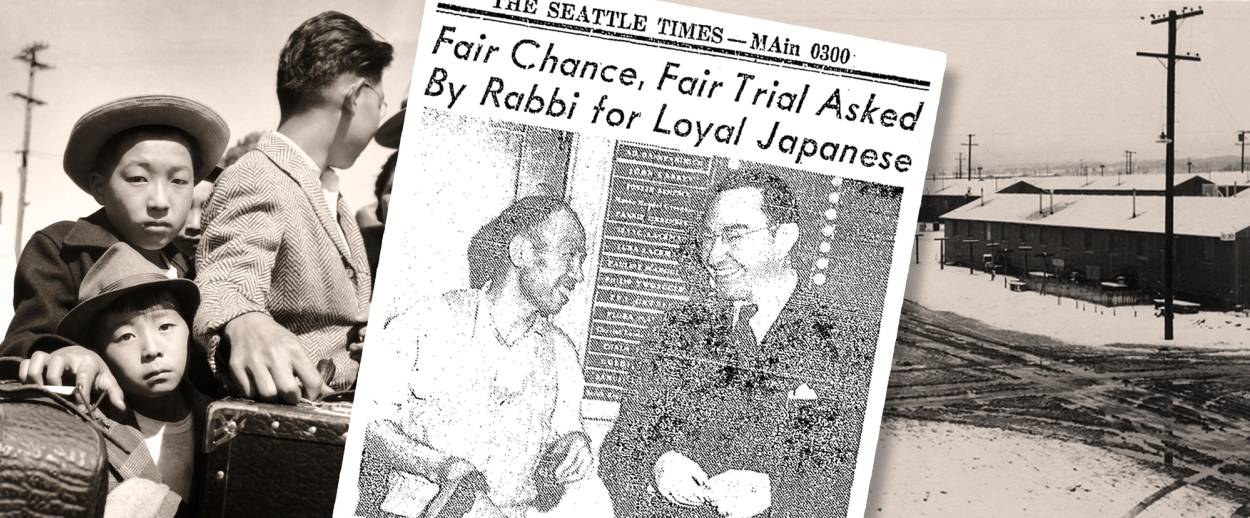

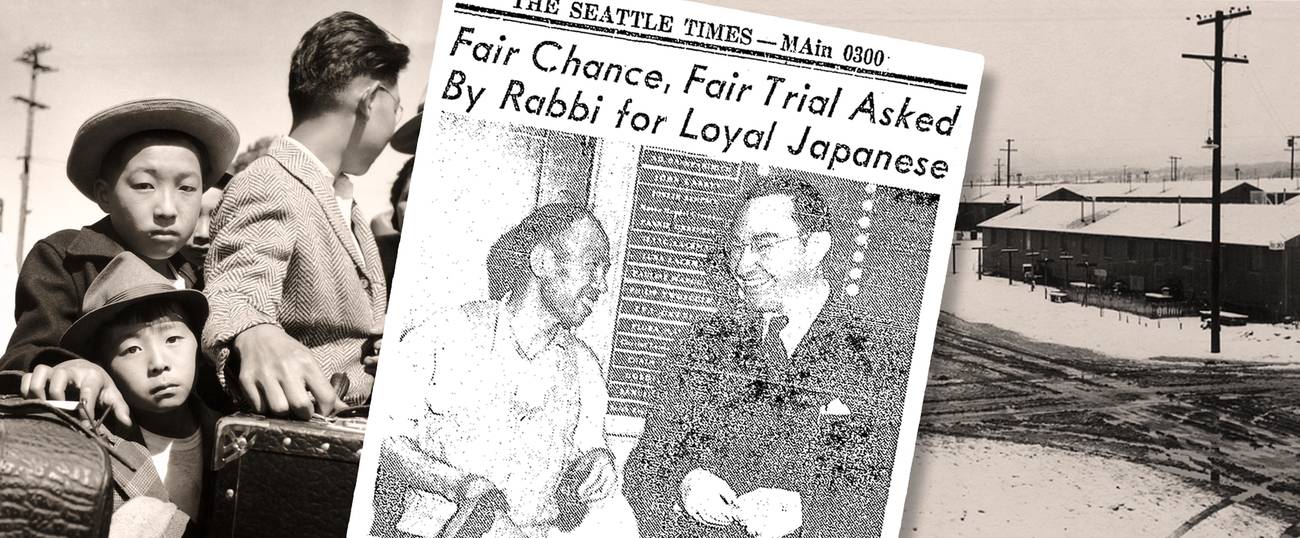

How a Seattle Synagogue Made News by Hiring a New Custodian

When Japanese immigrant Eddie Otsuka was released from an internment camp in 1945, nobody would hire him—except one rabbi who saw parallels in their personal plights

Seventy years ago this past spring, in March 1946—several months after Japan surrendered to the Allies on August 15, 1945—the U.S. government closed the Tule Lake Segregation Center. It was the last of the 10 internment camps where people of Japanese ancestry, including American citizens, living on the West Coast were forcibly relocated during WWII.

Some of the internees had been released and allowed to return to the West Coast before Tule Lake was finally closed for good, and before Japan had even surrendered. When one former Tule Lake internee returned to his hometown of Seattle to take a custodial job, it made the Seattle Times—on May 3, 1945—complete with a photograph.

Why would such an everyday event make the newspaper? Even today, when editors constantly scramble for content to fill a 24-hour news cycle, this little vignette about a custodian seems like a nonstory. The answer to this puzzle lies in the largely forgotten context of the anti-Japanese hostility along the West Coast at war’s end, and in the personal stories of the returning internee and the man who hired him.

In the newspaper photo, the former internee, Eddie Otsuka, clad in rumpled work clothes, shares a smile with Rabbi Franklin Cohn in the lobby of Seattle’s Herzl Congregation. It was Cohn who hired Otsuka to care for the synagogue’s building and grounds. Cohn had been the congregation’s spiritual leader for three years: He had arrived in Seattle to take the pulpit in 1942, around the time when the federal government was driving Otsuka, along with the rest of the West Coast’s Nikkei (ethnically Japanese) population, behind barbed wire fences.

Many Washingtonians, Oregonians, and Californians were nothing short of delighted when the federal government exiled Otsuka and the rest of the Nikkei on spurious claims of military necessity and locked them up in internment camps. Racial suspicions and economic envies had made the immigrant Japanese and their U.S. citizen children unwelcome along the coast for decades. War with Japan provided a rationale for forcing them from their farms and businesses and relieving them of much of their wealth and property.

Just as many whites celebrated when the Nikkei left in 1942, many were incensed at the thought of their return in 1945. In January of that year, a Japanese family returning to Placer County, California, was greeted with gunshots at their house from passing cars and an attempt to blow up and burn down one of their farm buildings. (The perpetrators were arrested and then acquitted.) February and March saw shotgun blasts at or into the homes of returning Japanese families in Fowler, Fresno, Vasalia, and Madera, California. Vandals set fire to houses in Selma and San Jose and a Buddhist temple and a Japanese school in Delano. In various communities, Japanese graves were defaced. In Hood River, Oregon, returning Nikkei were denied service in most local stores, and the American Legion chapter stripped from its war memorial the names of the community’s 16 native-son soldiers who were Japanese-American. The threats and violence sometimes extended not just to the Nikkei but also to white people who dared to help them: In one notorious incident, graffiti was scrawled on the Los Angeles home of the celebrated scientist Linus Pauling’s home when he and his wife hired a returning Japanese-American veteran to do some gardening.

The crisis drew attention at the highest levels of government. In a statement on May 13, 1945, that appeared in newspapers across the country, Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes denounced what he called the “planned terrorism” confronting Japanese-Americans returning to their homes on the coast from other internment camps that closed long before Tule Lake. He denounced the hooliganism as the work of “a lawless minority” that “seems determined to employ … Nazi-storm-trooper tactics against loyal Japanese Americans and law-abiding Japanese aliens.” This was a provocative analogy for a nation that had finally vanquished Nazism just five days earlier.

But it was an analogy that surely made sense to Rabbi Cohn, who had direct experience with the brutality of Nazism. Cohn was an immigrant himself—a refugee from Nazi Germany. Born in 1906, he trained at a seminary in Breslau and served the community there until 1937, when he moved with his family to Berlin to help German Jews relocate to Palestine as Nazi persecution mounted. He saw the dangers to himself and his family and planned to move to Palestine someday, after helping to secure safe passage for as many of his fellow Jews as possible. But he waited too long: During Kristallnacht in November 1938, he found himself kicked to the bottom of a Gestapo office stairwell while thousands of German Jewish men, including some of his own relatives, were marched off to concentration camps at Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen. Cohn knew that he could no longer delay emigrating. Early in 1939, at the age of 33, he fled to the United States with his wife and two children (and little else). Most of the rest of Cohn’s family could not secure visas or overseas sponsors and had to remain behind.

So when Cohn looked at the internal exile of the Nikkei of the West Coast, and the persecution they faced as they contemplated returning home, he saw a reflection of his own experience. Indeed, when he heard Otsuka’s story, he heard a version of his own: Otsuka was also an immigrant, born in Fukuoka, Japan, in 1903. He arrived in the U.S. in 1919. Cohn immigrated with the name of Fritz and became Franklin; Otsuka arrived as Eiichiro and became Eddie. On arrival, Otsuka supported himself by working in, and eventually managing, a Seattle hotel; Cohn spent his first six months in the United States selling ties on the streets of New York City. By fleeing Germany when he did, Cohn avoided imprisonment in the ghettos and concentration camps where his close relatives ended up. Otsuka had been forced with his wife from their Seattle home in June 1942, shipped to the barbed wire confines of Tule Lake in northwest California. Both men felt a deep commitment to their adoptive country; the United States had provided sanctuary for Cohn, and Ostuka told a loyalty board in 1943 that he “owed this country everything, my life.”

The two men shared one more melancholy point of connection when they met: Both were in suspense about the well-being of family members. It had been a long time since the rabbi had heard from the relatives he had left behind in Germany, and while he knew they must have suffered greatly, he would not learn for quite some time that seven of them had in fact been murdered. Otsuka’s nephew by marriage, Masao Ikeda, had volunteered for the U.S. Army in April 1943 and went off to fight in Europe with a segregated Japanese-American combat team. When Otsuka took the custodial job at the Herzl Congregation, he knew that his nephew was missing in action. Only much later would he learn that Ikeda had been killed in battle in France in November 1944.

What these two refugees from persecution shared was not lost on them. The Seattle Times story accompanying the photograph made clear that the rabbi offered to help Otsuka out of empathy rather than sympathy. “We have seen, during these last 20 years or so, how much prejudice can embitter life for individuals and as a group,” Cohn said to Otsuka. “You and I have been more or less in the same boat. I escaped from the Nazi[s] in Germany in 1939. Until November I was an alien … [and] had to prove myself … and I did.” The rabbi offered the custodian encouragement: “I know you will” prove yourself, he said, “because I have faith in you and in all Americans.” Otsuka, patting his chest, told Cohn that his heart was American and that all he wanted was “to be quiet … [and] see how things go.” Pointing to a rake he had just been using on the synagogue’s lawn, he allowed that custodial work was not what he knew, but “it was something, at least for now.” He wanted no trouble, Otsuka said; all he wanted was “to live in peace.” This seems such a modest aspiration, but in the context of the time, with hoodlums shooting up and burning down Japanese families’ houses, it was a lot to hope for.

It is tempting to imagine that what Cohn did was part of a broader American Jewish commitment to easing the plight of the Nikkei. But it was not. While a number of individual Jews, especially a handful of lawyers, advocated for the rights of Japanese Americans as the war went on, American Jews as a group were notably silent about the removal and imprisonment of the Nikkei of the West Coast in 1942. As Ellen Eisenberg documents in her book The First to Cry Down Injustice?, Jewish groups along the West Coast chose to keep their heads down rather than speak out against a program of exile and imprisonment that in some ways resembled the treatment of their fellow Jews in Europe. They were more concerned with firming up their own somewhat tenuous position as American insiders than with reaching out to a group that had long been a prototype of the outsider.

This evidently did not worry Cohn. He took a newsworthy risk in offering the job to Otsuka, and Otsuka took a newsworthy risk in accepting it. No harm ultimately came to either man from it, but that does not diminish the audacity of two immigrants connecting persecution abroad to persecution at home and modeling an American lesson in tolerance. “This is America,” Cohn said in the newspaper, “and loyal Japanese should be given a fair trial.” Future security for all nations lay, he noted, “in our willingness to accept now those loyal to our principles.”

Eric Muller is a law professor and writer living in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.