The Jews You’ve Never Heard Of

In the Bay Area, Karaite Jews struggle to build a future in America

On Oct. 3, as most synagogues around the world celebrate Rosh Hashanah, about 130 people will gather at a synagogue in Daly City, California, to celebrate Yom T’ruah, the biblical “Day of Shouting.” They will be just a few of the tens of thousands celebrating in congregations across Israel and Europe. The congregation will chant from a Torah scroll, recite their prayers in Hebrew, coddle bored children, and some might even—succumbing a bit to acculturation—dip apple slices in honey. But they will not blow the shofar, wish for each other to be inscribed in the Book of Life, or depart with a shanah tovah. In fact, they will not be celebrating the New Year at all. Rather, the Karaite Jews of America will be celebrating the first day of the seventh month of the Jewish calendar, a day of sacred assembly called for in Leviticus 23:24.

“The idea of the seventh month as Rosh Hashanah is a borrowed Babylonian concept,” Jonathan Haber explained to me over the phone one afternoon, while he took a break from a hiking trip in northern Israel. Haber, who grew up in a Reform Jewish home in Miami Beach, began practicing seriously as a Karaite while an undergraduate at the University of Florida. He recently moved to Israel, and in early August joined the Israel Defense Forces, complete with a letter from the Karaite Chief Rabbi that ensures he can celebrate the holidays by the Karaite calendar. “The four New Years in the Talmud are adopted from the Babylonian custom of having multiple new years, and that comes from the pagan idea of multiple gods. None of that is in the Tanakh,” he said, referring to the Hebrew Bible.

He’s right, of course. Rosh Hashanah as the start of a new year is a rabbinic interpretation of the verse. And since at least the eighth century CE, Karaite Jews across the world have kept to an interpretation of Judaism in which the Bible is taken as the ultimate authority on religious practice. Long centered in Egypt, Turkey, and Crimea, Karaites will consider the insights of the Oral Law, but they don’t accept their rulings as binding, and outright reject rabbinic traditions that contradict the plain meaning of scriptural verses. As Travis Wheeler, a convert to Karaism from Georgia who is the only formally trained Karaite shochet in the United States put it to me, “Any Karaite—any good Karaite—will read the Talmud” but the words of the Torah always take precedence—and that creed leads to a form of Judaism that is at once recognizable yet strange.

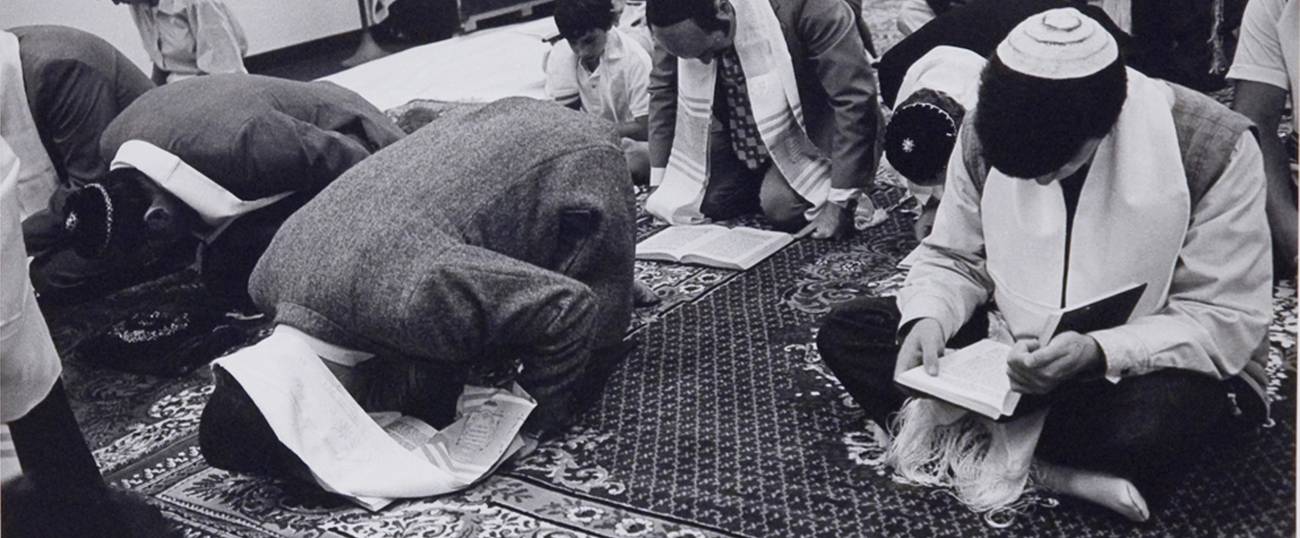

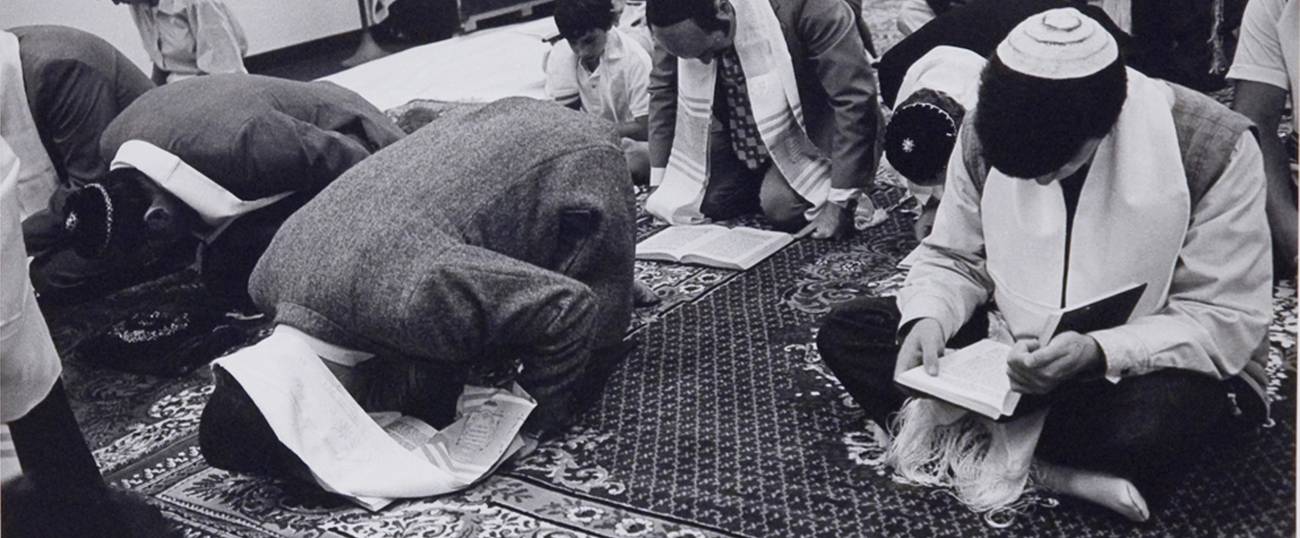

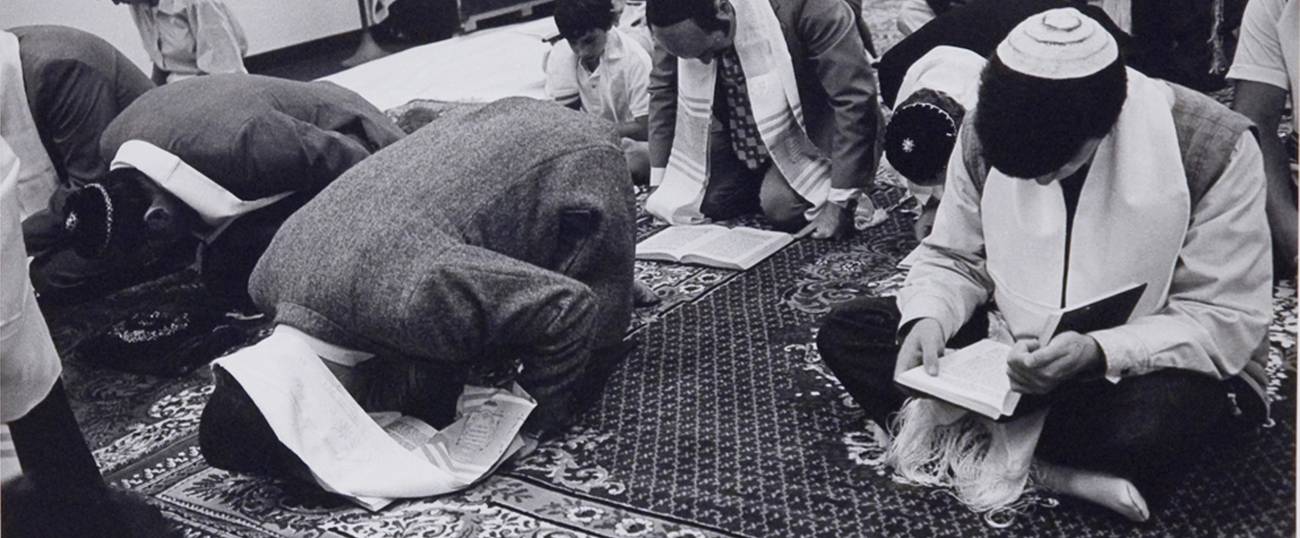

Karaite Jews observe kashrut, Shabbat, and the Jewish holidays (except Hanukkah), and they hold daily prayer services. But they will eat meat and milk together (provided the meat was not the child of the animal that produced the milk, in accordance with Exodus 23:19) and avoid shwarma, that classic Israeli street food, because the animal fat that flavors the meat from on top constitutes biblically forbidden chelev , a prohibition rabbinic law long ago overturned. Karaite tradition forbids women to enter the synagogue during their periods, yet allows women to divorce their husbands by right of the court, avoiding the problem of agunot. Karaites follow patrilineal descent. The Karaite siddur is mostly Psalms and prayers woven together from biblical verses. They remove their shoes in synagogue and pray prostrate on the ground. (To many, this looks like Muslim worship, but the practice is guided by Exodus 3:5, in which God tells Moses from within the burning bush to remove his shoes “because the place on which you stand is holy ground,” and by biblical depictions of Daniel and others praying on their knees.) They don’t require a minyan for communal prayer and they don’t lay tefillin, understanding the biblical commandment to bind the words onto one’s body to be intended symbolically. In some ways, the Karaites still live in the mind-set of the Talmud, where each scholar can consider and establish law according to his own understanding of the Bible. A Karaite motto, quoted in much of their literature, is: “Search scripture well, and don’t rely on my opinion.” This doesn’t make it a total free-for-all—like rabbinic Jews, Karaites derive law from scripture according to their own traditions, scholars, and standards of legal interpretation. They just don’t think man’s word can ever override the written word of God.

Few realize that there is an active Karaite community in the U.S.

For most Jews, “Karaite” evokes little more than a half-remembered comment in Hebrew school, perhaps something to do with the Sadducees of the Talmud, with biblical literalism, with heresy. Maybe, for the slightly more informed, something about Karaite status under Nazi Germany (more on that later). Misconceptions run deep. But while Karaites will often ring a historical bell, few realize that there is an active Karaite community in the U.S.

Comprising mostly Egyptian-Karaite Jews who fled or were expelled from Egypt in the 1950s and ’60s, after the creation of the State of Israel and then the Six-Day War, they found their way to the Bay Area, today the heart of the American Karaite presence. At first, the community would gather in each other’s homes to pray, and then in 1991, the Karaite Jews of America bought a house and established the Daly City synagogue, today the only independent Karaite synagogue in the country. A network held together by familial relations and connections from back in Egypt, they also held regular get-togethers and social events in addition to holiday and Shabbat celebrations. But for the most part, the community has existed outside the structure of the established American Jewish community.

This lack of awareness by the broader Jewish community is partly due to small numbers—there are about 250 Karaite families in the Bay Area, only several hundred more families in New York, Boston, and around the United States—and partly because the community itself has long kept a low profile. Most Karaites have a story or two about being rejected and mocked by other Jews, and the older generation especially felt no need to advertise their complicated status within the Jewish world, as immigrants being welcomed and aided by those very Jewish organizations.

But now, nearly half a century after their traumatic expulsion from their Egyptian homeland and already established in the United States, the Karaite Jews of America have seen a surge of interest from Jews and non-Jews alike. And as the historic generation of Egyptian Karaites grows older, there is new urgency to ensure the Karaite way of life continues here. The concern is not whether Karaite practice will die out all together: The stronghold of Karaism undoubtedly lies in Israel, where a community is said to be about 40,000 strong, comprising the bulk of practicing Karaites in the world, and on which the Daly City community relies for religious guidance and instruction. But in America, the future of the movement lies not with those who have cultural ties to Karaism, but those who, somewhere in life’s journey, become convinced of its truth.

“When I came to the United States, nobody knew what a Karaite was,” Remy Pessah told me one morning in the Daly City synagogue, which they call the KJA, for the Karaite Jews of America organization. “We did not even have a synagogue yet.” She was warm and friendly, like nearly all the Karaites I meet. I had been to services here only once before, and yet when I walked in a second time, I am greeted like family. By the time I left San Francisco, I had been invited to stay in over four different people’s homes. Remy’s husband, Joe Pessah, has been the acting rabbi for years, and Remy organizes many social gatherings, tapping into cultural Karaite interest for community. But outside the KJA, her Karaism isn’t something she discusses much.

“Coming from a minority within a minority within a minority, [as a Jew from the Middle East who was a Karaite] you know, it’s a lot,” Remy Pessah said. “So I said to all my friends that I am a Sephardic Jew. And I had a lot of friends who were Sephardic Jews, including one of my very best friends, who was from Spain. One of those days, after being very close friends for many years, Joe was being interviewed by the Jewish Bulletin. And his picture was on the cover, the front page, as the ‘Karaite acting rabbi: Joe Pessah.’” She laughs at the memory, taking my hand for emphasis. “And who read that paper but my friend Rebecca? And she comes to me: ‘Remy, you lied to me! You are a Karaite and you never told me! Why did you never tell me?’ And I said to her, ‘Rebecca, you don’t understand. It is nothing about being ashamed. It is just going through the whole process to explain who is a Karaite and what is a Karaite and the whole thing.’”

She sighed. She is invested in keeping the community strong for those who came from Egypt, but she feels little need to reach beyond it. Her husband’s cousin, Amin Pessah, agrees. He left Egypt in 1968, at 18, and like most of the Egyptian Jewish community, he first went to Italy, with the help of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. He, his mother, and several of his siblings got out on Spanish passports, which were good for one day only, before arriving in Italy. His father and older brother, like many Egyptian Jewish men, had been rounded up and taken by the government. In Italy, when people would ask, he would just say he was a Jew from Egypt, which in and of itself was taken as exotic.

“They would say, ‘Oh, we didn’t know there were Jews in Egypt,’” Amin Pessah told me. The cultural surprise cut both ways. “We never heard of the Hasidic in Egypt!” he recalled, of meeting European Jewish communities. “We never saw Hasidic Jews walking, with the beards. We never knew they existed.”

For many, fleeing Egypt and rebuilding a life in America brought so many changes that holding onto their little-known way of Jewish life seemed all but impossible. A lot of Karaites simply assimilated into the broader Jewish world. Many children of Karaites I spoke with grew up knowing they were this thing called Karaite, but didn’t know what it meant; few felt motivated to investigate. One woman recalled to me the experience of being married off, within weeks of her arrival, to a Sephardic man her brother had met, and being taken to the mikveh before their wedding night, terrified. Karaite Jews don’t have a mikveh, and she did not understand the ritual, but when her gruff mother-in-law-to-be told her to take off her clothes and step into a pool of water, she did.

“The thing is, most Jews today don’t understand that they themselves are operating as a subset of the larger Jewish paradigm,” Shawn Lichaa said to me one morning, as we chatted in the entrance to the KJA synagogue amid a crowd of about 50 local Karaites, who were there for a memorial service for Ben Pessah, Joe Pessah’s brother. Lichaa estimated that he was related to 80 percent of the room. “Jews laugh when I call them Rabbanites, because they’ve never heard the term,” he continued, using the word Karaites use for Jews who follow the rabbinic tradition. “They’ll say to me, ‘I am a Reform Jew or I am a Hasidic Jew,’ but they don’t realize that all of those movements are following rabbinic dictates to varying extents.”

Lichaa has made the future of Karaism in the United States his life’s purpose. A 37-year-old lawyer in San Francisco, he doubles as the unofficial spokesperson for all things Karaite in America, giving interviews on his morning commute and spending his weekends and evenings presenting on Karaite Judaism to high schools and synagogues. His blog, A Blue Thread, a title that plays off the unusual looking tzitzit, or ritual fringes, of Karaites, is one of the most widely read resources on Karaite Judaism in English online, along with Karaite Korner, run by his friend and mentor, Nehemia Gordon. Nearly all of the Karaites I interviewed for this article asked first if I had spoken with Lichaa. He learns weekly with an Orthodox rabbi and has built relationships with Chabad and across Jewish movements. The child of two Egyptian-Karaite parents, he has a historical connection to the tradition, but also believes that the time is ripe for greater outreach and education.

‘I cannot realistically create a significant revival of historical Karaism in the U.S. But I can create a revival of Karaite thinking.’

“One important thing is to dispel the notion that Karaites are strict literalists,” he said. “Karaites are not literalists, they are textualists.” This is a point I will hear many times: Karaites do not just follow the plain meaning of the text. In fact, it is giving the unique Karaite mode of hermeneutics more Jewish airtime that most excites Lichaa. “Realistically, the historical line of Karaites will die off,” he told me later in the day, as his 15-month old son Reuven crawled over the synagogue carpet. “That, I am honest with myself about.” The previous Shabbat, Reuven had been the only child in the building. “I cannot realistically create a significant revival of historical Karaism in the U.S.,” he said, pausing to pick up Reuven, who was now giggling and flipping the pages of a chumash. “But I can create a revival of Karaite thinking.”

When I asked why he wants a Karaite revival, he said it’s for the sake of all Judaism. “People are walking away from Judaism, daily,” he said. “There are Jews out there who are less observant because they don’t know that there is another option for them, they don’t know that a lot of the things they have learned about the Jewish belief system don’t have to be true. There are people with questions who haven’t even seen Karaite perspectives.” But it’s not just about offering an alternative. It’s also about truth. “We view ourselves as the original and the most historical way to do this,” Lichaa said.

For Haber, the soon-to-be soldier, finding Karaism made sense of Judaism. As he started learning Talmud and Bible in college, he was shocked by the incongruities between current Jewish practice and biblical text. He sought a tradition where he could practice as he believes God explicitly told him to. Today, he eschews warm food on Shabbat (because of the prohibition on fire, and also because you pay for heat when it’s on, so he considers it to be spending money on Shabbat), wine at his Passover Seder (because chometz yayin can be taken to mean a paschal prohibition on all fermented foods), and follows the Karaite holiday calendar determined by monthly moon sightings (and, for some still, the annual ripening of the barley season in Israel), often making his holidays a day or two off from mainstream Jewish calendars.

“The reason I’ve started doing this,” he said, “is that I truly, with all my heart and all my soul and with everything in me, think this is what God intended for me and the Jewish people and this is the way to do it, and this is it.” As to the recent interest in Karaism, he added, “I don’t think people should try out Karaism because it’s cool or different or ‘why not try,’ but because it is nachon, it is right, it is what God wants from us.”

For many Jews, this piety can be hard to grasp. Karaites like Haber and Lichaa are generally part of mainstream American life, and yet speak with the type of religious conviction usually the purview of the ultra-Orthodox.

“God gave us a Torah.” explained Hakham Meir Rekhavi, the chancellor of the Karaite Jewish University, an online institution established in 2005, from his London office. Hakham, meaning sage, is an honorific similar to Rabbi, used in Karaism and certain Sephardic circles. “He gave us the choice to go by it or not, but he said that if you don’t go by it, this will happen, and if you do go by it, that will happen,” he said, referencing the biblical blessings and curses. He is funny and insightful, but he speaks with an intensity I rarely hear in the Jewish world. “Once we understand the whole option of the Torah and the premises, there is no option. We are Jews. We have a mission on the earth to be a holy nation, and by fulfilling the Torah, we accomplish that.”

Does he think Rabbanite Jews—that is, the rest of us—are fulfilling their role in the Divine Mission?

“No, I honestly do not,” Rekhavi said. “A lot of them, when it comes to praying at graves and saint worship, have honestly gone so far astray as to be considered avodah zara,” or idol worshippers. “I look upon rabbinate Judaism, in a way, as during the time of the divided kingdom, when the north went astray; they are still our brothers, but they went astray. Doesn’t mean they are outside of the family.”

Since 2007, Rekhavi, himself a convert to Karaitism, has overseen the conversions of almost 100 non-Jews to Karaite Judaism, and has educated many more historical Karaites and Rabbanites into the faith. Until recently, Karaite Judaism didn’t event accept Rabbanite Jews, let alone non-Jews interested in conversion. But, in recognition today that the community needs new blood, Rehkhavi, along with several others, developed a conversion ceremony based on the undertaking of vows and using the text from the Book of Ruth. Through the KJU, many people convert as couples, and he tries to guide those living in countries with unique difficulties. He believes that in order for Karaism to survive, it must adapt, and that means accepting outsiders. Like Lichaa, he believes the world is on the cusp of a Karaite revival, and he sees this as part of the coming redemption.

“All those who come in are of the pioneer spirit,” Rekhavi said. “These are the people who in the 19th century would have been going off west to see what is on the other side of the mountain.” He predicts that, soon enough, less adventuresome souls may give Karaism a try. “Once communities start growing, then I imagine that part of the mindset will begin to change, and it will be less of just those not afraid to step into the water first, and more who are open to crossing the bridge, but only once others have tried it and they know that it is secure.”

“I guess I come from the furthest away from Judaism there is,” James Walker told me one afternoon. Soft-spoken but deliberate, he speaks like somebody who has given over his story many times. “My wife and I have parents who are fervent and active African-American evangelical members, and I mean active as in serving as clergy and as volunteer church members.”

The Karaite fidelity to scripture has become the source for an unlikely group of converts.

The Karaite fidelity to scripture has become the source for an unlikely group of converts, those like Walker who grew up in devout Christian faiths and are eager to follow the Bible as the word of God. In high school, Walker met his first Mormon, and soon began investigating all kinds of faith communities.

“I started to look into these other faiths, into Mormonism, Catholicism, and others which had a lot of adherents but I knew nothing about,” Walker said. “All these faiths claimed to be following the Bible, but most of them had some component of tradition or authority that overrode the authority of the Bible, whether it was Catholic tradition or the Book of Mormon or the Watchtower publications.” Inspecting his own tradition, he began to wonder about its fidelity to the original sources. “I realized there was a lot in my church I wasn’t getting. At this point, I started learning Hebrew, and comparing Bible translations, and I saw that in fact there was a lot in the Bible that we didn’t keep.”

Walker, who can now translate Hebrew, Koine Greek, Judeo-Arabic, Syriac, Amharic, and Ge’ez, took a journey through a number of movements, ultimately became dissatisfied with the divinity of the New Testament, and finally found the Karaites. A few years ago, he and his wife converted though the KJU, and when their son was born, he brought in a Karaite mohel to circumcise him in the Conservative Jewish synagogue he attends in North Carolina.

As an African American, Walker believes the Egyptian identity of the Karaite community actually made it easier for him to connect, and he loves that he gets to now be one of those faces of the community.

“I look at the Torah as literally God’s guidance,” he said. “And I know I can scrutinize the Torah, and I do, looking at every commentary on every line, and it will stand up to whatever questions I might have. I have a lot to learn from the Orthodox world, yes, but at the core of all Judaism, in every synagogue, is a Sefer Torah.”

Converts like Walker and others help the project of expanding Karaism beyond its specifically Egyptian identity, something seen as critical to keep it going.

“Once the older generation of Egyptians who came from Egypt to America have died, their children will have fewer ties to Egypt, less reminiscing or connection to Egypt,” Rekhavi said. “So basically, the Egyptian way in America is dying out. Once the last person who remembers Egypt is dead, the Egyptian way will be a thing of the past.” But Rekhavi is not concerned. “There is a different community that is growing stronger. You know, through death comes birth, and that has to be important, that Karaite Judaism in the U.S. isn’t wholly wrapped up in Egyptian-ness.”

Nearly all Karaites have been told at one point or another that they’re not Jews, or not “real” Jews, or have been questioned about their practices, sometimes ridiculed. Enough that many are reluctant to volunteer that they are Karaites. Rekhavi recalls how, when he began exploring Karaism as a yeshiva student in Jerusalem in the 1980s, he was both threatened with hell and bribed with cash to stay a Rabbanite. But scholars say this skepticism toward Karaites is a recent phenomenon, and misguided.

“The Karaites were always considered Jews, everyone considered them Jews, there was never any problem considering them Jews,” Marina Rustow, a professor at Princeton University, told me one afternoon in a cafe on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. “Until the czars.”

Rustow’s book, Heresy and the Politics of Community: The Jews of the Fatimid Caliphate, argues that relations between Karaites and Rabbanites in the early period were much more intimate than people imagine. One of her most intriguing pieces of evidence is the numerous marriage contracts we have for Karaite-Rabbanite couples, and while the contracts show careful negotiating—clauses insist that the Karaite partner be allowed to celebrate holidays according to his or her calendar, and not be forced to eat the meat of a pregnant animal or light candles before Shabbat—these marriages had the full consent of the communities. It’s true that both Saadiah Gaon and Maimonides, in the 10th and 12th centuries, declared the Karaites heretics, but with little practical effect on relations. And Maimonides, despite his charge of minim, which can mean either heresy or the milder fault of sectarianism, still allowed religious interactions like visiting the Karaite sick and circumcising their sons, and he doesn’t even seem to have forbidden intermarriages.

While the movement’s popularity has waxed and waned since their golden age in 11th and 12th-century Egypt, it has always persisted. The one place where Karaites may have been the majority community was in Crimea, which tended to be more widely learned than its Egyptian counterpart. According to Daniel Lasker, of Ben-Gurion University,, from the early modern period until the mid-20th century all the chief Egyptian Karaite rabbis were imported from Crimea, or from Turkey. The brides were as well. Oddly, there is scant female interest in Karaism. Outside of the older Egyptian community, I couldn’t find any women for this article, and the subject of marriage was a consuming concern for many of the men I spoke with. When I visited the Karaite synagogue in Jerusalem for Shavuot services, I was of course first asked if I was menstruating, and then, once allowed in, promptly proposed to. I’m pretty sure it was a joke, but the lack of single female Karaites is seen as a serious problem.

Astonishingly, just one generation later, the Karaite communities of Crimea have completely disavowed their Jewish heritage. While, the Crimean Karaites began distancing themselves from the rest of the Jewish community in the late 18th century, in an attempt to avoid the harsh, anti-Semitic policies of the czarist governments, it wasn’t until recently that the break became complete. Lasker recalled visiting a Karaite synagogue in Lithuania recently. “When we walked in, the head of the community put on a kippa and genuflected, but it was so strange because none of them know anything of Karaite tradition or Judaism; they don’t want to know Hebrew, and they’ve convinced themselves that they’re not Jews and never had anything to do with Jews, but rather are derived from a Turkish pagan group.” He noted that there are Karaite cemeteries all over Lithuania, and that in Trakai (also known as Troki) he saw a Karaite cemetery with rubbed-out Jewish stars on the graves, and that the community had removed the stars from the top of their synagogues, and replaced them with the Seraya Shapsal’s pagan coat of arms. Some of these Karaites came to Israel with the wave of Soviet Jews; there is one active Crimean Karaite in Ashdod, a cantor who remembers his grandparents’ Jewish practice, and is trying to reach out to other Crimean Karaites as Jews. But most Karaites from Crimea, whether in Israel or still at home, want nothing to do with Judaism.

When people today talk about the Karaites as non-Jews, it may be the Crimean community that’s to blame, and not the Egyptian one, though people often don’t realize there is a distinction. “Rabbanite Jews in Eastern Europe felt betrayed by the Karaites,” Rustow explained, adding that a central aspect of the Karaite argument was they could not have killed Christ because they were ethnically distinct from the broader Jewish community. “The Karaites had exculpated themselves from the charge of deicide without contesting it for the Rabbanites. They felt the Karaites had hung them out to dry.”

It was the Crimean Karaites who were deemed not Jewish by the Nazis in WWII. By the time the Nazis got to Warsaw, they realized there was a Karaite community, and sought out several rabbis, including Meir Balaban, to ask if the Karaites were Jewish. Balaban had just published a book arguing that the differences between Karaites and Rabbanites were mostly a 19th century construal, and how for most of Jewish history there hadn’t been much difference. But when asked by the Nazis, he completely disavowed their Judaism. Given the circumstances, his and other rabbis’ rulings obviously can’t be taken at face value, but it completed an internal move by the Crimean Karaite community to distance themselves from Judaism that had already been well underway.

Karaites count under the Law of Return, and their marriages, divorces, and conversions are recognized under their own religious court system in Israel.

By contrast, the Egyptian Karaite community has always identified strongly as Jewish, an identity that was accepted by the broader Egyptian Jewish world as well. In fact, in 1950, when the community was being evacuated from Egypt by Israel, the Israeli government initially refused to recognize Karaites under the Law of Return. Shocked, the rest of the Egyptian Jewish community refused to continue making aliyah for an entire month until their Karaite Jewish neighbors were also allowed. Today, Karaites count under the Law of Return, and while it’s complicated, their marriages, divorces, and conversions are recognized under their own religious court system in Israel.

A worldwide Karaite renaissance is unlikely. The Bible as the absolute word of God is not today’s fight, and the demanding nature of Karaite practice, as all-consuming as Orthodox Judaism, seems prohibitively high for those just casually interested. Karaism, while an intriguing testimony to the diversity of early Judaism, has a hard theological demand that seems almost quaint, if not medievalist, to the way most people consider their religious commitments. The Karaite project has ceased to be threatening. There may be 40,000 Karaites centered in Ramle and a few thousand in the Bay Area, but the Rabbanites have clearly won the fight of history. In fact, the rigor of their lifestyle might be the reason Karaites have never been that popular, or never sparked the type of solo scriptura reform that cleaved Christianity in two.

But there will always be a group of people, I would hazard, who, baffled and frustrated by rabbinic authority, find in Karaism an appealing refuge. For those sold on Karaism as God’s truth, rather than just an escape route from other practices, this is hardly comforting. For Rehkavi, the call to personally engage with and struggle with the meaning of the Bible is foundational to Jewish life, even if it’s hard. And he, Lichaa, and others, will continue to fight the good fight. “Every religious person should struggle with God,” said Rekhavi. “Isn’t that what Israel means? Didn’t Jacob have to struggle with God? And it left him damaged?”

But for the older generation of Egyptian Karaites, for whom the Karaite Jews of America is a way to connect to family and friends, the continuation of the specifics of practice is less concerning. “I’m basically committed to any form of spirituality that offer substance to somebody,” said Abraham Menashe, who was born into a Karaite family and left Egypt with his mother and siblings when he was 10, though his current religious identity is fluid. “So if the Karaite community passes away, it’s only because it has stopped giving life to its members. I would mourn, then, only for the memory of what it once was.”

Shira Telushkin is a writer living in Brooklyn, where she focuses on religion, beauty, and culture. She is currently writing a book on monastic intrigue in modern America.