Festival of Candles

Celebrating Hanukkah—and my grandfather’s birthday—whether behind drawn curtains in Latvia or openly in Canada

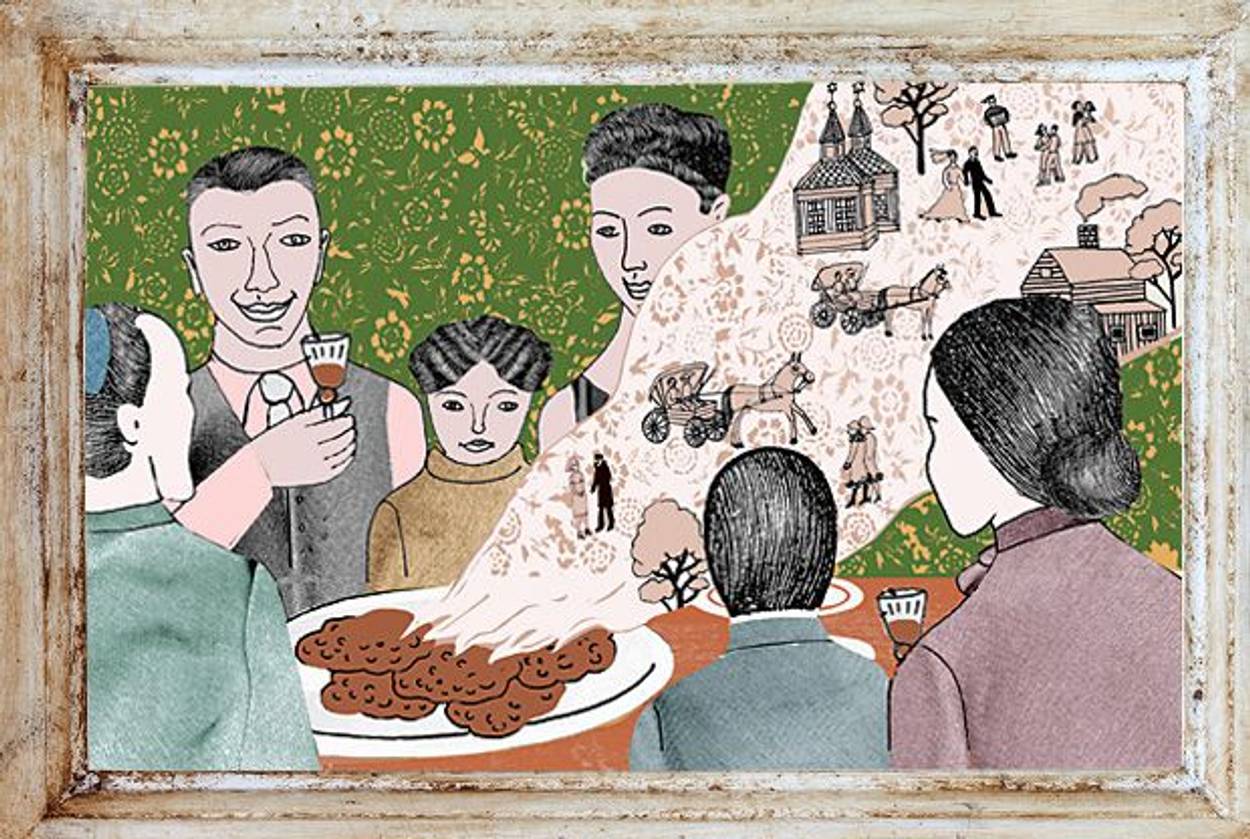

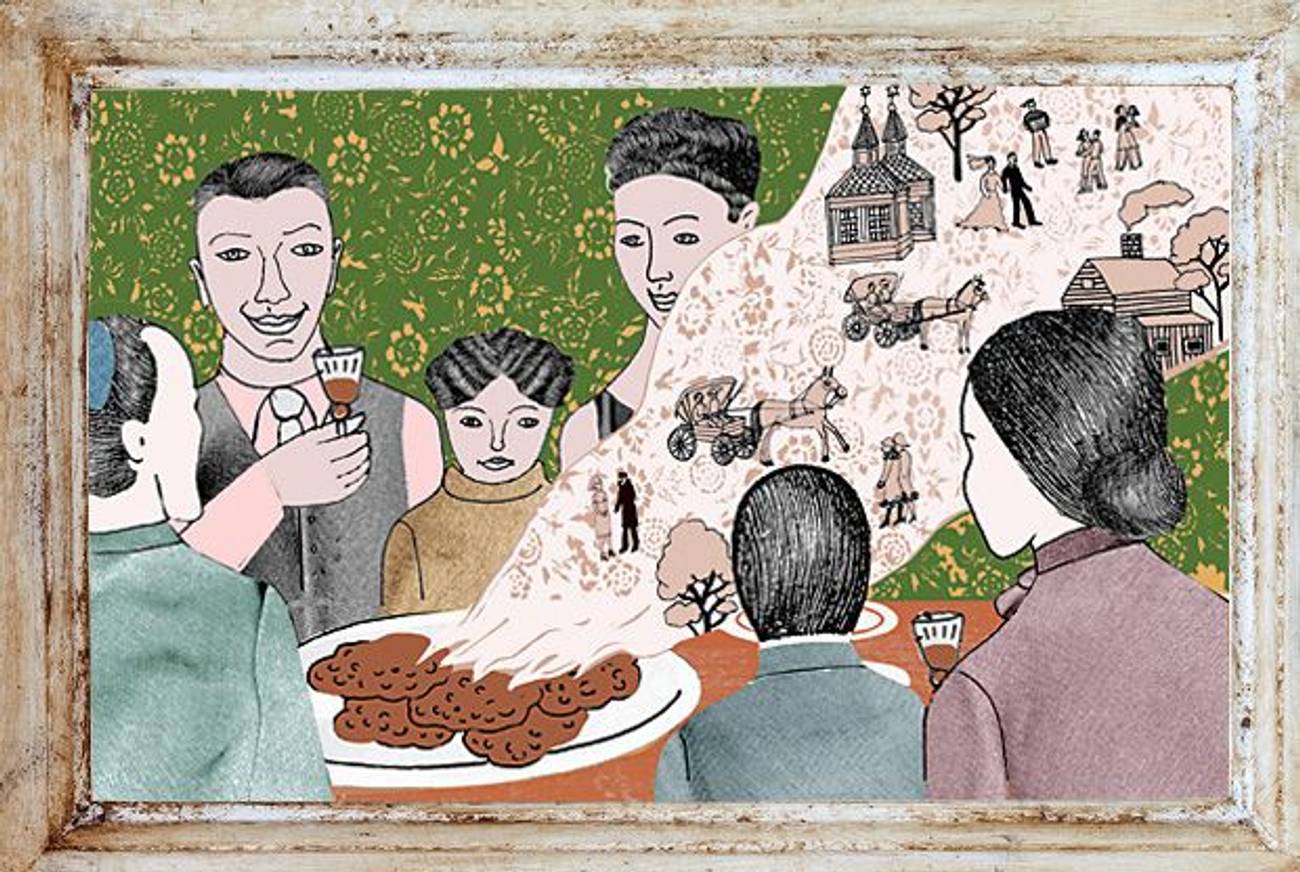

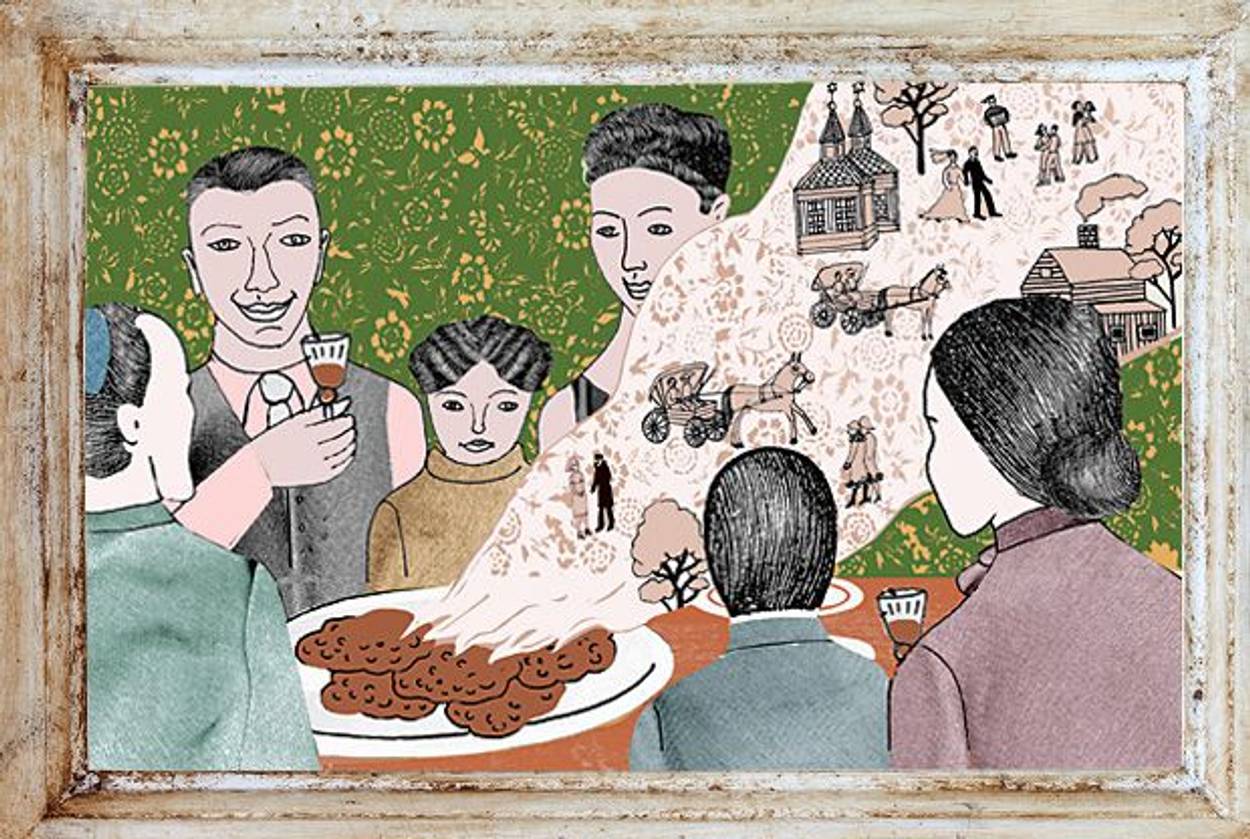

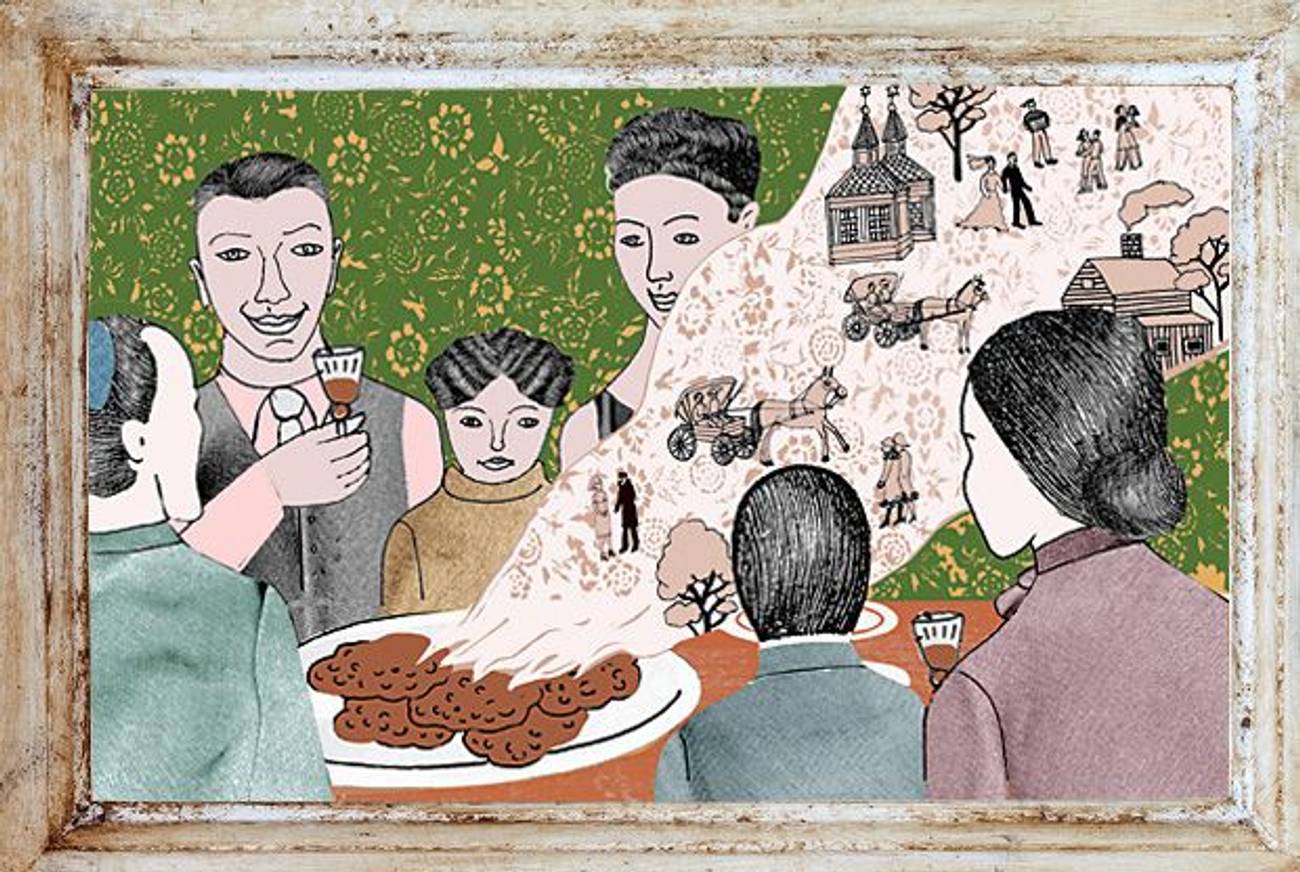

My grandfather, Yakov Milner, was born in November or December of 1915 in the Latvian town of Baltinava, at the edge of the Eastern Front. He claimed as his earliest memory the rumble and menace of artillery. The rest of his childhood memories were almost uniformly idyllic. Until the onset of the next war, he lived in a kind of a Yiddish fairy tale—a sweet, remarkably peaceful interlude between calamities. His father was a respected merchant who owned a general store and a boot-making workshop where Jews and Latvians cobbled amiably together. Family, community, and Jewish tradition ordered daily life. To the east and to the west the type was being set for a death sentence, but in Baltinava my grandfather went to synagogue, attended festive weddings, and observed the holidays. So deeply was he a product of this fading world that he, like others of his generation, only knew his birthday according to the Hebrew calendar. And although his passport arbitrarily gave as his birthday the 20th of August, we always celebrated the occasion on the proper date, varyingly in November or December, on the eighth day of Hanukkah.

I was born on June 2, 1973, in what had by then become the Soviet Socialist Republic of Latvia. If my birthday coincided with a Jewish holiday, I do not know it. The Communist revolution had obviated Jewish religion and replaced it with the teachings of Lenin and Marx. Any attempt to uphold Jewish tradition was considered subversive and so most Jews relinquished the traditions and aspired instead to be model Soviet citizens. Ostensibly, my family was also composed of model Soviet citizens—university graduates, esteemed professionals, even a few Party members—but during Jewish holidays we gathered at my grandparents’ house, drew the curtains, and engaged in subversive activities. The main provocateur was my grandfather, whose commitment to Judaism never wavered. For Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Purim, and Passover, the curtains were drawn and the family gathered. And, every year, on the eighth day of Hanukkah, my grandmother fried potato latkes, the curtains were drawn again, and we celebrated my grandfather’s birthday. I was a child at the time, kindergarten-aged, and for everyone’s protection—lest I disclose the dark family secret—the nature and significance of these gatherings were never explained to me. Instead I was told that we were marking my grandfather’s birthday. Thus, to my childhood mind, my grandfather was singularly blessed with four or five birthdays each year.

This episode is part of the family lore which, like lacquered wood paintings, feather pillows, and Russian translations of Sinclair Lewis, we brought with us to Canada. My memory of it is not very distinct. Memories of family life begin for me in the northern suburbs of Toronto, which became home. Here, liberated from Lenin and Marx, we made an effort at resuming the old ways. I was sent to Hebrew school. My father dutifully gave money to support the Jewish Russian Community. For the High Holidays, my parents dressed up and chatted with their friends outside the junior high school that served as a makeshift synagogue. And yet, fundamentally, we did not change. To experience a sense of solidarity with God, the Jewish people, and each other, we still gathered around my grandparents’ dining room table—albeit with the curtains open. We didn’t become more observant, only less anxious. Customs which we had neglected in Latvia—eating kosher, keeping the Sabbath—we mostly neglected in Canada. But the rituals which we had performed furtively there we now performed more elaborately here.

Hanukkah, for instance, saw us making a concerted attempt to light candles on each of the festival’s eight nights. After dinner, often with a hockey game on in the background, my father and I would obediently retrieve the yarmulkes from a cupboard, place them briefly on our heads, whereupon I would recite the prayers and validate my Hebrew school education. Inevitably, we would skip a night or two, but the general point would have been made: That which was forbidden in Riga could be done with Semitic impunity in Toronto.

Hanukkah mornings, particularly on the weekends, I would wake to the enticing aroma of potato latkes. I would descend and find my mother standing by the stove, continuing a tradition that no commissar had managed to disrupt. At my grandparents’ apartment I would find my grandmother in the identical stance: having peeled and grated dozens of potatoes by hand, she would be poised above a sizzling frying pan. “Yasha, cum essen,” she would call, and my grandfather would join me at the cramped kitchen table, where a container of sour cream would be set amidst chipped plates. If I had to isolate an enduring image of Hanukkah and Jewishness this would be it: sitting in their clean, modest kitchen, eating the rich, oily food, listening to their affectionate fussing, their Yiddish.

My grandmother died in January of 1999, bringing to a painful conclusion many things, but most acutely, the 53 years of my grandparents’ marriage. The division of responsibilities they had established—to him the spiritual; to her the practical—made us wonder how he would be able to manage by himself. His confusion and disarray reflected our own. Without my grandmother’s contribution, her presence, her cooking, it was difficult to envision our future. How could we continue with family gatherings, holidays, birthdays? In Russian, my mother, aunt, and uncle, repeated the mournful refrain: She will be forever lacking. My grandfather nodded sagely, intoned my grandmother’s name, and cried.

And yet gradually, over a period of months, as if recognizing that he must now embody everything, my grandfather started to assume some of my grandmother’s responsibilities. We would visit him and he would lead us into the kitchen and ask—with a mix of apprehension and pride—that we sample his cabbage, his farmer’s cheese, his jam. And nearly a year after my grandmother’s death, for Hanukkah and his birthday, we came to his apartment and smelled the familiar smell. In his slow, meticulous manner, he had worked for much of the day, and he beckoned us into the kitchen, apologizing that they were not hers, but inviting us to try, taste, take more.

This essay originally appeared in the November 2006 issue of Canadian House and Home and is reprinted by permission of the author.

David Bezmozgis is the author of The Betrayers and the collection Natasha and Other Stories.