Portraits of the Artists

At the height of the AIDS epidemic, photographer Robert Giard captured a generation of gay and lesbian writers, many of them Jewish

In the 1980s, I lived on the east end of Long Island with my first life partner, the American photographer Robert Giard. We were close to the epicenter of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York City, and the disease had a devastating impact on our lives. Both of us, with our different skill sets, immersed in the epidemic, our daily conversations about work alternating with the latest updates on friends and former lovers. After three years of fundraising and activism, I joined the full-time staff of a small community-based AIDS agency.

Bob immersed himself in a different way. In 1985, he was gripped by a particular sense of urgency after attending a performance of Larry Kramer’s play The Normal Heart, the walls of the black-box theater evocatively painted with the names of many people we knew who had succumbed to the disease. He soon began a photographic project to document the two-decade-long flowering of gay literature before much of its creative talent disappeared; it would eventually encompass over 500 lesbian and gay writers and activists. And naturally, people of the book that we are, many of those he photographed were Jewish.

From the outset Bob was inclusive rather than exclusive in his approach. He photographed those who were already well known—Allen Ginsberg and Adrienne Rich—as well as then-emerging authors like Bernard Cooper and David B. Feinberg. He was interested in novelists, poets, journalists, historians, scholars—anyone who wrote and identified as gay, lesbian, or otherwise queer. He began with those closest to home and soon found his way into lesbian communities that at the time were in one degree or another separatist and suspicious of the male gaze. From there he identified subjects in the African-American and Latino/a worlds and ultimately among Native Americans.

As the project grew, Bob traveled across the country, always at his own expense, always by public transportation. Because he never learned to drive, he spent the weeks before each trip poring over maps and bus-company timetables, the least expensive and grittiest way to travel the country. When he arrived in an area, like a medieval troubadour, he was often referred from one writer to another, to the little known poet down the road and to the aspiring novelist in a neighboring town.

Bob’s inclusiveness stemmed in part from never losing touch with his roots as a child of working-class parents who achieved no more than sixth-grade educations. Slotted for a factory job when he entered high school, he was singled out by a supportive teacher who moved him from a vocational to an academic track where he excelled, earning a full scholarship to Yale University. When we met in 1971, we were both teaching at small progressive schools in New York, although with his background in literature and interest in film, he was already imagining a turn toward photography. He made that decision in 1974 when we moved to Amagansett, where we lived until his death in 2002 at age 63.

Bob prepared carefully, his bedside table piled high with the books and unpublished manuscripts of authors he was planning to photograph. Traveling with him to the rural South and Northern California, I saw how he put people at their ease by quickly telegraphing that he knew and cared about their writing. Yet even as he talked, his eyes darted around looking for the best setting for the portrait. He asked questions about objects that might become part of the picture. James Saslow casually slings his ballet slippers over his shoulders, Esther Newton lovingly embraces her dog, and Joan Nestle clasps a plaster mask of two women for our admiration.

I knew some of the writers by reputation and learned about others from Bob as their images emerged in the brightly color-coded trays that were laid out on long boards across the tops of our kitchen counters to form a makeshift workspace in our tiny house. I met Irena Klepfisz when she came to read at the East Hampton Center for Contemporary Art, the walls lined with Bob’s portraits of woman poets. Yiddish had been part of my childhood and Irena spoke about its revival, read in both English and Yiddish, and gave me a copy of the book she had recently edited. Saslow, an art historian, became a good friend after Bob’s death and I am still moved when he tells how affirming it was as a younger gay scholar that Bob wanted to photograph him. Playwright Tony Kushner, photographed clutching a pillow of Karl Marx that he sewed himself, as was his wont during reflective moments, engagingly recounted that in the years of his yo-yoing weight he waited for just the right moment to be photographed.

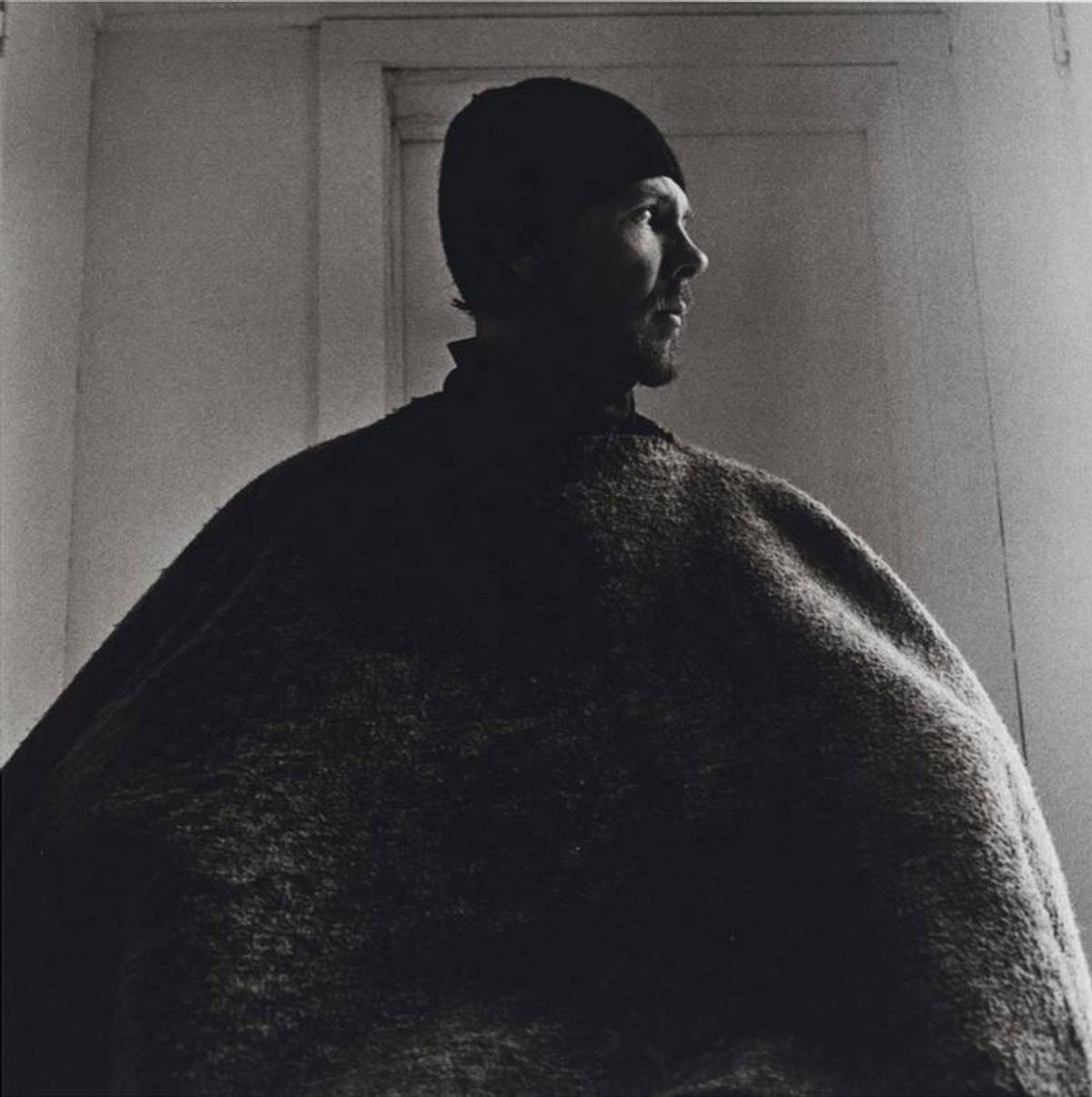

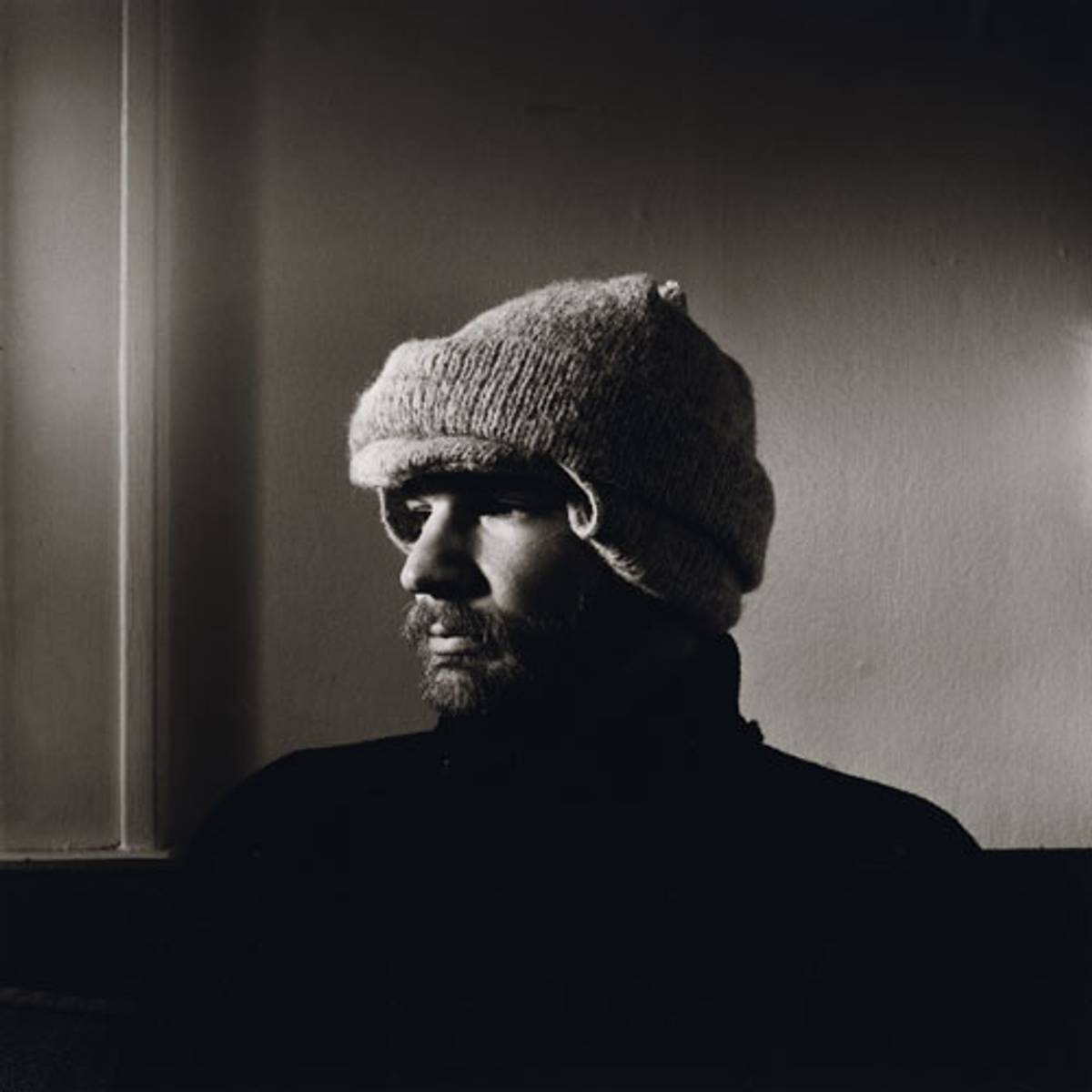

In the early years Bob photographed me often. An available and amenable model, I knew that he focused on what I was doing or wearing, like the winter hat pictured here. As time passed however, I became a more impatient sitter, too eager to get back to my desk, go out for a run, or finish dinner preparations. Even when I initiated the shoot, a formal portrait for a book jacket or speaking engagement, I was not a friend of the camera. Too self-conscious, too stiff, too reluctant to smile, I left an anxious, disinviting image on the photographic paper as if, in the end, I really didn’t want the reader to buy this book or attend that lecture: portraits of ambivalence.

At a time when writers of all genres were documenting the past and present of lesbian and gay culture and succumbing to AIDS in unimaginable numbers, Bob captured their lives for future generations. He wrote of his own work:

It is my wish that tomorrow, when a viewer looks into the eyes of the subjects of these pictures, he or she will say in a spirit of wonder, “These people were here; like me, they lived and breathed.” So too will the portraits respond, “We were here; we existed. This is how we were.”

And that is exactly what I think his portraits do, how they work. The difference is that now the “we” has taken on a new meaning and includes the photographer as well as the photographed. The portraits speak about his life, and my life with him, as much as the life of a given subject.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jonathan Silin is the author of four books including Early Childhood, Aging and the Life Cycle: Mapping Common Ground. He is a fellow at the Mark S. Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, University of Toronto and was the life partner of the American photographer Robert Giard. He lives in Toronto and Amagansett, New York, with his partner David Townsend.

Jonathan Silin is the author of four books including Early Childhood, Aging and the Life Cycle: Mapping Common Ground. He is a fellow at the Mark S. Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, University of Toronto, and was the life partner of the American photographer Robert Giard. He lives in Toronto and Amagansett, New York, with his partner, David Townsend.