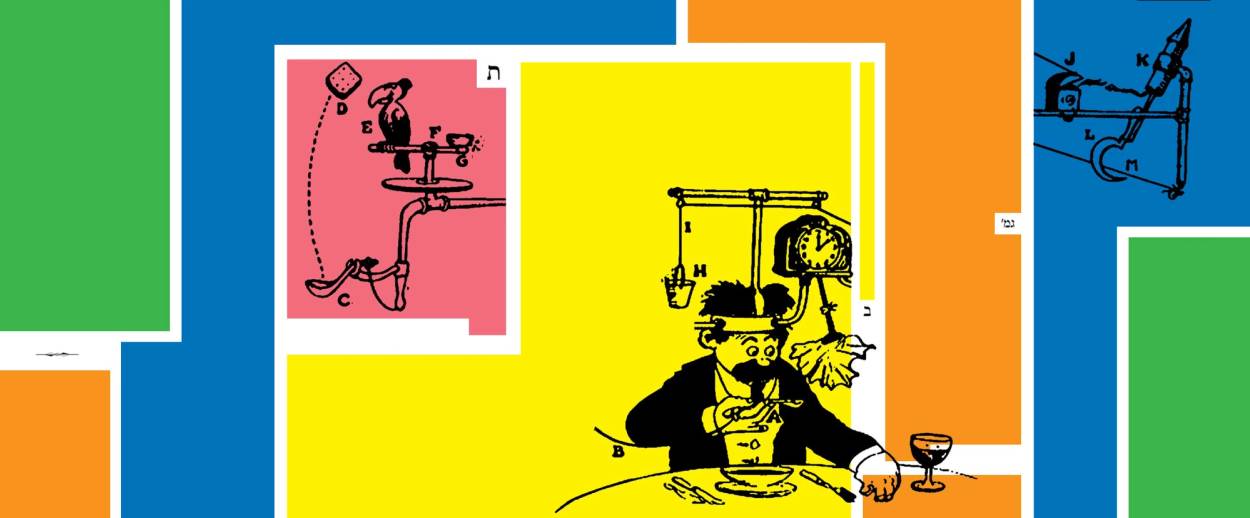

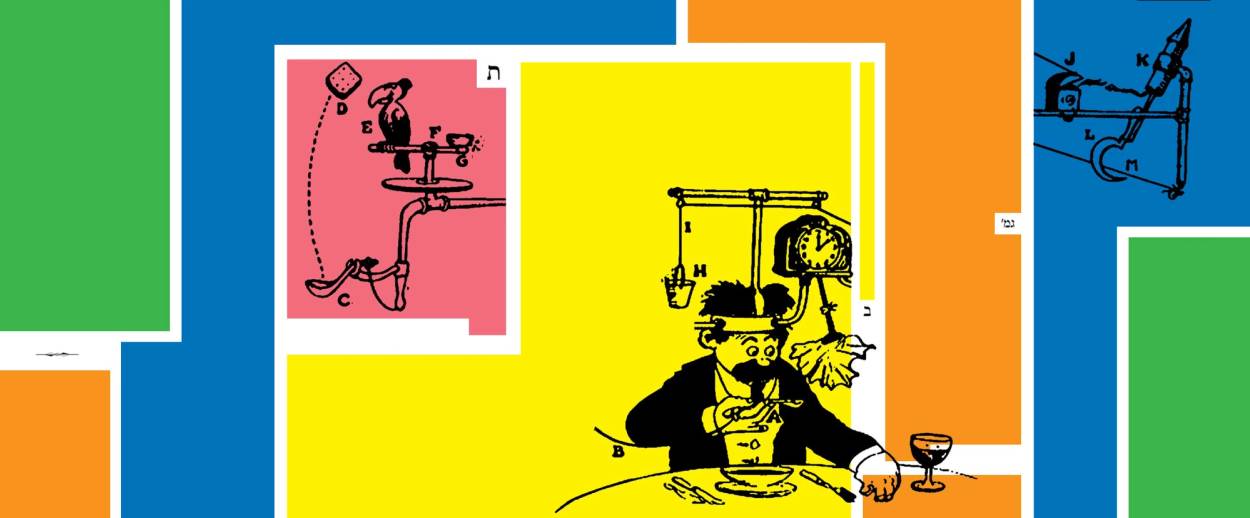

The Talmud as Rube Goldberg Machine of the Mind

In this week’s ‘Daf Yomi,’ one rabbi finds a way out of a complex problem with meal offerings other rabbis created

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

This week, Daf Yomi readers began a new tractate, Menachot, which continues the Talmud’s analysis of the Temple service. Where the previous tractate focused on slaughtered offerings, however—the sacrifice of animals, ranging from bulls to birds—Menachot deals with meal offerings—the offering of flour, which is often accompanied by oil and frankincense. The tractates are clearly parallel, since many of the same questions that arose with regard to slaughtered offerings are also pertinent to meal offerings. Thus Menachot begins, like Zevachim, by considering the problem of offerings sacrificed with improper intent—that is, when one type of offering is made for the sake of a different type.

The procedure for meal offerings is similar to that for animal offerings. An animal sacrifice entails slaughtering an animal, catching its blood in a bowl, conveying the blood to the altar, and then “presenting” it by sprinkling it on the corners of the altar. Depending on the type of sacrifice, some or all of the meat is burned, and whatever is left over is given to the priests to eat. With a meal offering, there is obviously no slaughter or blood involved; instead, the officiant scoops up a handful of meal and presents it on the altar, leaving the remainder for the priests to consume.

In the first mishna in Menachot 2a, we learn that, for meal offerings as for animal offerings, proper intention matters. “All the meal offerings from which a handful was removed not for their sake are fit for sacrifice, but these offerings do not satisfy the obligation of the owner.” That is, a miscategorized meal offering may be offered on the altar without offending God, but the person who offered it still has to go back to the beginning and do it again the right way.

In Zevachim, this basic principle went unchallenged. But in Menachot, we hear a disagreement from Rabbi Shimon, who holds that “All the meal offerings from which a handful was removed not for their sake are fit for sacrifice and they even satisfy the obligation of the owner.” For instance, there are two kinds of meal offerings that are supposed to be cooked with oil in a pan. One is a “pan offering,” which uses a regular shallow pan and produces a hard, flat pancake, and the other is a “deep pan offering,” which produces something more like a soft loaf. If a person is supposed to bring a pan offering and he actually brings a deep pan offering, then according to the mishna, he must start over again. But Shimon suggests that the deep pan offering will do on its own.

What is the reasoning behind Shimon’s claim? As the Gemara explains in Menachot 2b, he holds that “meal offerings are not similar to slaughtered offerings.” That is because the various kinds of slaughtered offerings all involve the same actions: “There is one manner of slaughter for all, and one manner of sprinkling the blood for all, and one manner of collection of blood for all.” A witness observing an animal sacrifice would not be able to tell whether it was, for example, a sin offering or a guilt offering. This means that intention alone is what differentiates them: A sin offering is a sin offering because the person bringing it intends it to be a sin offering. And that is why a wrong intention can be disqualifying for an animal sacrifice: Intention has the power to change the very nature of the sacrifice.

But with meal offerings, Shimon points out, things are different. A deep pan offering uses a different amount of flour than a pan offering; likewise, a dry offering consisting only of flour, which is offered by a penitent sinner, has different ingredients from a regular meal offering, which includes flour and oil together. You could tell just from seeing the offering what kind of offering it was meant to be. As Shimon puts it, “The Merciful One does not disqualify improper intent that is recognizably false,” because its recognizability means that it is not actually an incorrect version of the intended offering; it is simply a different offering altogether.

The Gemara immediately recognizes, however, that this principle, which Shimon restricts to meal offerings, could in fact be applied to some slaughtered offerings as well. For instance, a bird sin offering has its blood sprinkled below the red line that divides the altar into upper and lower halves, while a bird burnt offering has its blood sprinkled above that line. Thus, if one set out to offer a sin offering, but sprinkled the blood above the line, by Shimon’s reasoning one did not offer an improper sin offering, but a proper burnt offering. “The actions performed on it prove that it is a bird burnt offering, because if it is in fact a bird sin offering, he would perform the sprinkling below the red line,” the Gemara reasons. Therefore, there is no reason why such an offering should not affect acceptance. But this contradicts what we learned on the subject in Zevachim, where an incorrect intention was disqualifying. The Gemara engages in a long discussion trying to find ways to reconcile Shimon’s views, but in the end, he remains in the minority.

The next mishna, in Menachot 6a, gives a catalog of things that can disqualify a priest from performing a meal offering. Here, too, there is a parallel to Zevachim, where we heard a similar list. An offering is invalid if offered by a non-priest, or a priest who is an acute mourner, or one who is uncircumcised, or not wearing the correct priestly clothing. Among these imperatives is that the priest must use his right hand to scoop up the meal, never his left. But what happens if a priest accidentally uses his left hand?

According to Ben Beteira, the error can be remedied simply by returning the handful of meal to the original vessel and removing a new handful with the right hand. But the Gemara goes on to specify that this is only the case so long as the handful has not been put into a sacred service vessel. If it has, then it is ritually disqualified and cannot be returned to the original bowl. However, the rabbis come up with an ingenious workaround. The meal can be returned by placing it, not directly into the “furrow” created when it was taken out, but on the rim of the bowl, It will then fall into the furrow of its own accord, without technically being placed there. As the Gemara says, “it is as though a monkey returned it”: That is, no human being is responsible, and so the meal is not disqualified. In this way, the rabbis manage to find a physical escape route from the ritual obstacle course they have created.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.