Out of Ghetto Streets

When Jewish immigrants came to Canada a century ago, they weren’t always welcomed with open arms

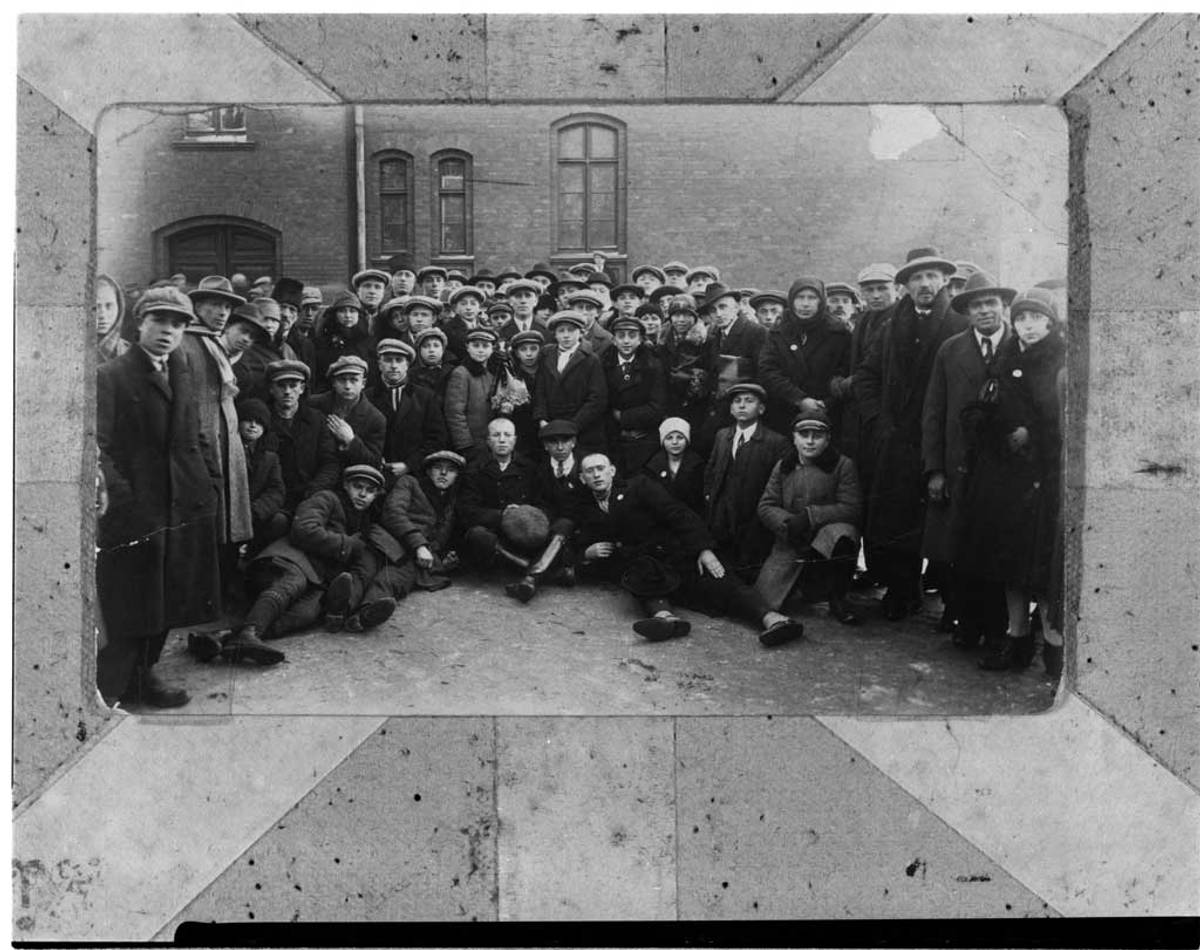

During the first two decades of the 20th century, Canada’s total Jewish population increased from 16,401 in 1901 to 125,197 in 1921, which represented 1.42 percent of the country’s total population. Much of this increase owed to the arrival of thousands of Russian and Eastern European immigrants, who were not especially welcomed with open arms.

Whether they lived in Montreal with a Jewish population of 45,803 in 1921, Ottawa with 3,041, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, with 599, or Brandon, Manitoba, (130 miles west of Winnipeg) with 222, Jews were all generically classified as “Hebrews” by the non-Jewish world, which did not appreciate or even understand the religious and ideological distinctions within the larger Jewish community, or its ancient disputes. Canada was and remained primarily white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant. In 1912 and 1913 the country received 776,626 immigrants, of which 39 percent were British. And by 1921, English, Scottish, and Irish (many Roman Catholic) Canadians accounted for approximately 53 percent of the country’s total population. Add in the French, Germans, and Scandinavians, and Canada was overwhelmingly Northern European. Nevertheless, Jews, Italians, Ukrainians, and other Eastern Europeans attracted a lot of attention—and little of it positive.

The ever-increasing number of Jews in Toronto, for example, was disturbing for the white Protestant majority. In 1921, the city’s Jewish population was 34,770, which was only 6.6 percent of the total; yet it was 30,000 more than there had been two decades earlier. They were a highly visible group, segregated as they were in the Spadina–Kensington Market area. The Toronto Globe’s editors raised an alarm about “a Jewish invasion of the public schools.” And the Toronto Telegram expressed grave concerns about the opening of the new and impressive Beth Jacob synagogue on Henry Street in 1922. Two years later, the same issue was addressed even more virulently by the Telegram. “An influx of Jews puts a worm next the kernel of every fair city where they get a hold,” an editorial stated. “These people have no national tradition. … They are not the material out of which to shape a people holding a national spirit. … Not on the frontiers among the pioneers of the plough and axe are they found, but in the cities where their low standards of life cheapen all about them.” In the minds of politicians, public health officials, church leaders, teachers, journalists, and members of the business community, the Jewish, Southern and Eastern European, and Asian newcomers were members of objectionable “races,” who dressed in peculiar garb, ate food with garlic and other Byzantine spices, and spoke strange languages. It was the conventional wisdom of the day that these immigrants contributed to the growing poverty and congestion in downtrodden urban neighbourhoods where drunkenness, crime, and prostitution flourished.

There was some truth to these charges. Around St. Lawrence Boulevard in Montreal, the Ward in (downtown) Toronto, and the North End of Winnipeg, many Jewish immigrants indeed lived in abject poverty in slum housing (often rented from Jewish landlords) where disease was rampant. In 1906, a group of ladies from the Winnipeg Ministerial Association visited a North End Jewish home and reported on the appalling living conditions they discovered. “Forty-five families inhabited a very small space, living in a manner that was to say the least disgraceful,” the ladies wrote. “Diseases of all kinds were common. … It was just the spot for a plague to begin and sweep over the city, and it was providence that such had not occurred.” In Montreal in 1908, Jewish cemeteries did not have room for the large number of Jewish paupers who required free burial.

There may not have been many Jewish brothel owners or pimps, but small-scale bootlegging was definitely popular among Jewish immigrants as a way to make a few dollars. The long list of Jewish bootleggers included Getel (Gertrude) Shumacher (the grandmother of Toronto civic politician Howard Moscoe) who followed in the footsteps of her brother Shmuel, who was also a bootlegger, and sold shots of whiskey out of the self-styled “grocery store” located in her house in Toronto’s Ward neighborhood to supplement the family income; the parents and grandmother of Toronto Jewish boxing champion Sammy Luftspring, who offered their clientele 25-cent glasses of rye; and Abraham Bellow in Montreal. By 1923, Abraham, then 42—and the father of 8-year-old Saul, destined to become one of the great American writers of the 20th century—was up to his neck in debt. He had already failed as a baker, dry goods salesman, junk dealer, marriage broker, and insurance agent, among other pursuits. Bootlegging was a last resort and a poor choice: He and his partner were beaten and robbed while driving to the Quebec-New York border with a truckload of whiskey.

Across the country, Jewish communities—large, medium, and small—quickly learned that no one was responsible for the welfare of their members except the communities themselves. The success of these various endeavors owed mainly to the philanthropic efforts of selfless individuals, among them two remarkable women, Ida (Lewis) Siegel and Lillian (Bilsky) Freiman, both born in 1885. Siegel was from Pittsburgh, but as a young girl came to Toronto with her mother to reunite with her father, who had found work in the city. She was (like her older brother Samuel Lewis) a committed Zionist, and in 1906, at the age of 21, she was instrumental in organizing a group to assist young Jewish immigrant women and mothers—only the first in a long list of her volunteer achievements. She actively promoted education for girls, sports for Jewish children, and was one of the founders of Hadassah, the most notable Zionist women’s group in Canada.

Lillian Freiman and her husband, Archie, were also committed Zionists. Thirty years old when the First World War broke out in 1914, Lillian spearheaded numerous charitable activities. She supported the Red Cross, raised money for orphanages and refugee efforts—in Ottawa, she was later known as the “Poppy Lady” for her pioneering work promoting the poppy campaign for veterans—and became president of the Dominion Hadassah women’s organization. Siegel and Freiman set the standard for others to follow. And, as a response to the many needs of the Eastern European immigrants, ladies’ Hebrew benevolent societies were organized in nearly every Canadian Jewish community across the country.

Still, there were grumblings about Jewish self-segregation and the impact of the newcomers from established Jews such as Montreal lawyer Maxwell Goldstein, who in 1917 became the first president of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies, which evolved into the Combined Jewish Appeal. In a 1909 interview with London’s Jewish Chronicle, he bemoaned that the cause of many of the community’s problems was “the vast influx of foreign Jews into the Dominion [of Canada].” These immigrants, he added, “form ghettos among themselves and create a great deal of prejudice.” The great irony of this classic Catch-22 situation would have been lost on Goldstein. Jews could not win, no matter what they did. If they remained poor and ghettoized, they were disdained as a cancer on Canadian society. On the other hand—at least until the 1960s—the more acculturated Jews became, the more they were resented by the Christian majority for being too pushy and for threatening the status quo.

Compassion and understanding for this deplorable situation only went so far among large segments of the WASP majority. There was, in fact, a backlash against undesirable minorities, the result of a deep-seated xenophobia that was to remain a part of un-multicultural Canadian society at least until the 1960s. Expressing a widely shared view, Frederick Barlow Cumberland, a British-born Ontario writer and sportsman, declared to the members of Toronto’s Empire Club in 1904 that “we are the trustees for the British race. … We hold this land in allegiance.” French-Canadian nationalists were of the same mind: In 1911, while addressing an Anglo-Canadian meeting, journalist Olivar Asselin complained about the “exotic babbling” Jews in Montreal, who in his view had degraded the city’s character. (Asselin later reconsidered his attitude toward Jews, and condemned French-Canadian anti-Semitism.)

In an age when the eugenics movement, with its theories about the alleged link between biology and morality, was popular, Canada—or so it seemed— was under siege from unwanted “foreigners” and “aliens” who could never assimilate to “Canadian” values and standards. In future Labour politician Reverend J.S. Woodsworth’s book Strangers Within Our Gates, published in 1909, the saintly and compassionate Social Gospel advocate—who in the face of the severe urban problems of the early 20th century preached an activist Christian charity to improve the lives of the poor and destitute—and politician outlined his belief (shared by many others) that British, Scandinavian, German, and French immigrants would make much better Canadians than “Hebrews,” Slavs, and “Orientals” (Chinese, Japanese, and Hindus). The prospects for “Negroes” and “Indians” (Indigenous Canadians) were even more dismal.

Public school teachers ultimately tasked with “Canadianizing” the immigrant children were likewise skeptical. Teachers encouraged their foreign students to learn English by any means possible—and, more significantly, imparted to their young charges the “correct” moral values. This meant teaching them respect for law and order and having them embrace “thrift, punctuality, and hygiene.” As one Toronto public school teacher put it, Canadians are “tidy, neat and sincere—foreigners are not.” The conservative Winnipeg Telegram summed up such fears even more concisely. “Better by far to keep our land for children, and children’s children of Canadians,” its editors argued in mid-May 1901, “than to fill up the country with the scum of Europe.” Such anti-immigrant sentiments would persist in Canada for the next several decades.

Excerpted from Seeking the Fabled City: The Canadian Jewish Experience. Allan Levine, © 2018. Published by McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House of Canada Limited. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Historian and writer Allan Levine’s most recent book is Details Are Unprintable: Wayne Lonergan and the Sensational Café Society Murder.