Oil Change

In this week’s ‘Daf Yomi’ Talmud study, discussion of proper meal offerings displays the circularity and uncertainty of rituals recreated from a destroyed culture

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

One of the things that makes studying Talmud difficult is that the text takes a lot of prior knowledge for granted. After all, the Talmud was not written as a manual of Judaism, designed to instruct people how to reconstitute it from scratch. Rather, it takes the form of questions and debates that arose from daily practice. In the case of Tractate Menachot, for example, priests in the Temple did not need to consult a text to learn how to bring meal offerings; they saw it happening every day and learned by doing. It follows that the tractate does not begin by explaining what a meal offering consists of, how it is prepared, or how it is sacrificed.

Rather, the first mishna in the tractate, which Daf Yomi readers read back in August, asks whether an offering that is brought for the wrong purpose is still valid. In other words, the Talmud focuses on specific problems that may arise during the carrying out of the ritual, rather than explaining the ritual itself. The result is that the Talmud student can be left in the dark on basic matters.

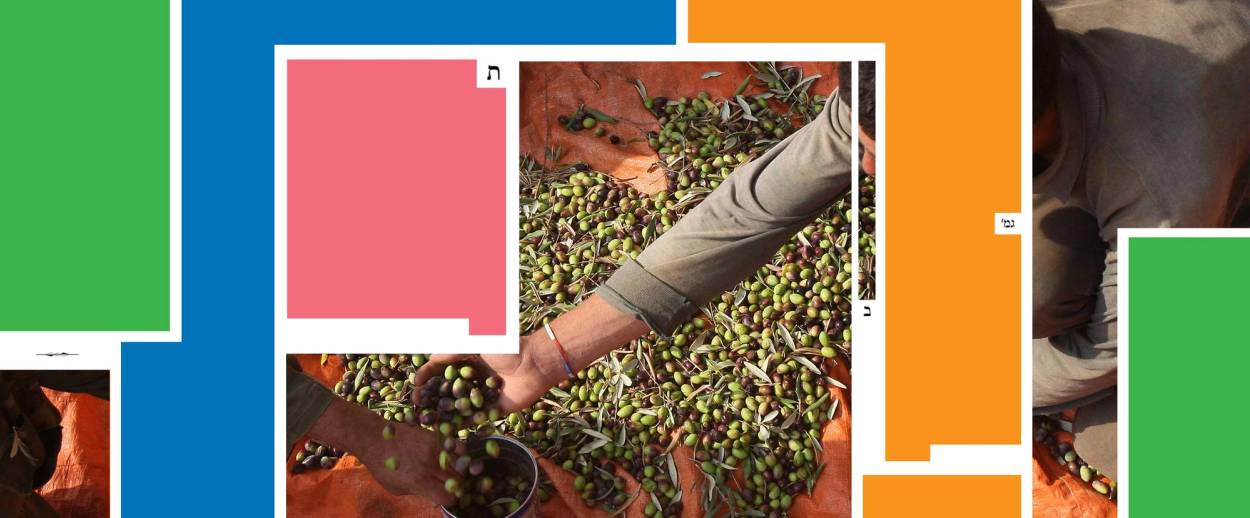

For instance, over the last few months, I have been wondering about how exactly oil is used in the preparation of meal offerings. The rabbis make clear that meal offerings usually involve an admixture of oil, but at what stage of the offering does this addition take place? At first I thought that the oil must be mixed directly into the flour, so that a handful of the mixture can be removed and burned on the altar. But in other places it’s suggested that the oil is not applied until after the meal is baked into loaves.

Not until last week, in Chapter Seven, did the answer become clear. As the mishna in Menachot 74b explains, “all the meal offerings that are prepared in a vessel require three placements of oil.” First oil is applied to the pan itself, as a coating; then oil is mixed into the flour before baking; and finally oil is applied to the surface of the baked bread. As usual, the rabbis prefer to cover all the ritual bases: This way, you never have to be uncertain whether you’ve added oil at the correct stage of the offering.

But this three-stage process only applies to offerings “prepared in a vessel”—that is, the particular meal offerings that the Torah says must be baked in a pan. Most meal offerings, however, are not prepared in pans; they are baked in an oven, producing loaves—which, as we learned earlier, are almost always matza, unleavened bread. How is the oil applied in this case?

This is a subject of disagreement among the rabbis. Yehuda HaNasi holds that the loaf is baked first without oil, and then it is broken into pieces that are mixed with oil. The rabbis, on the other hand, say that the flour is mixed with oil before baking, and then more oil is applied after the loaves are baked. The Gemara explains how this is done: The priest “places oil in a utensil and then places the flour into the utensil”—in this case, we can imagine the utensil as a bowl or baking sheet. “And he then places oil upon it and mixes it, and kneads it, and bakes it. And then he breaks it into pieces, and he again places oil upon the pieces, and he removes a handful for the altar.”

As far as I can tell, this means that handfuls are removed at two stages of the process—first from the flour and then again from the baked loaf. But this may not be correct—this is one of those areas where the rabbis’ indirect method allows confusion to flourish. What is clear is that there is a prescribed technique for breaking the loaves into pieces. Just what that technique is, however, depends on who you ask.

According to the rabbis, the sacrificial loaf is broken in half and then broken in half again, creating four large pieces. According to Rabbi Shimon, on the other hand, the loaf is entirely broken up into small bits no larger than the size of an olive-bulk. (This is a standard measure of volume in Jewish law.) Meanwhile, Rabbi Yishmael has yet another recipe: He says that the loaves should be “crushed until he restores them to flour,” that is, the baked loaf is pulverized into the consistency of meal.

All these ambiguities and disagreements suggest that, even to the rabbis themselves, the exact steps of the Temple ritual had become obscure. After all, the Talmud was compiled centuries after the Temple was destroyed and the meal offerings had ceased to be brought. What we have in the Talmud is the rabbis’ logical and imaginative reconstruction of a practice known to them only from texts. In other words, it is not just the modern student of the Talmud who is often groping in the dark when it comes to authentic ancient Judaism; the rabbis themselves shared this uncertainty.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.