Jews on the Prairie

The rise and fall of Beersheba, a Jewish agricultural colony that brought immigrants to Kansas in the 1880s

Eight miles from Garden City, Kansas, in a remote landscape of corn fields without end, punctuated only by pheasants and blackbirds, lies an unexpected discovery: several gravestones, the only physical remains of Beersheba, a Jewish agricultural colony established in 1882.

Beersheba’s existence was an outgrowth of the surge in Russian Jewish migration to the United States in the 1880s. After Russia’s Czar Alexander II was assassinated in 1881, his son, Czar Alexander III, rescinded his father’s more lenient policies toward Jews. Overnight, Russian Jews were prohibited from owning or leasing land, and subjected to days-long pogroms that began in Kiev and quickly spread throughout the region.

Concerned about both the welfare and perceptions of their backward-seeming, Eastern European co-religionists, American Jewish leaders sought options for settling the newcomers without “burdening” the established Jewish community.

The civilization of those (Russian Jews) is in form entirely different from ours. Will they become good citizens of this country? They must become that or we have no use for them. Unless they do that they will disrupt our social status and may do considerable damage to the reputation of our co-religionists.

—Isaac Mayer Wise, American Israelite, May 1882

The Beersheba colony was conceived and funded by the Hebrew Union Agricultural Society, the brainchild of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, founder of the American Jewish Reform movement. While Wise’s idea of Jewish agricultural settlement was not original—Russia was the birthplace of Jewish back-to-the-land movements focused upon the Holy Land (Bilu) and the United States (Am Olam)—Wise financed the Beersheba project through appeals in his publication, American Israelite. Beersheba community members would homestead in Southwestern Kansas, capitalizing on the U.S. government’s promise of 160 acres to any citizen or would-be citizen who improved their acreage, built a dwelling, and resided there five years. In June 1882, Wise implored “all men who have pity on those maltreated and outraged Jews to send us at once as much money as they think proper to spend in this most charitable enterprise.”

By July 1882, the society selected 59 men and their families, “all sound and robust looking people,” to populate the settlement. Rabbi Wise’s own son, Leo Wise, accompanied the colonists to Kansas City to furnish them with supplies and guide them to their new home near the Pawnee River. In addition to a Sefer Torah and a shofar, the agricultural society provided tents, farming implements, and livestock.

Initially, Beersheba’s progress was promising. The colonists built a 60-foot sod schoolhouse that doubled as a synagogue. They dug wells, farmed sorghum and kitchen vegetables, cared for both farm and domestic livestock, and warmed their houses with cow chips collected from the nearby cattle trails. They celebrated at the synagogue, danced and prayed, and observed the Sabbath. The first of several weddings took place in 1883 between Abram Cohn (aged 21) and Minnie Schwartzman (aged 18), officiated by the community’s rabbi and shochet, Moses Edelhertz.

By most accounts, the newcomers were welcomed by their gentile neighbors, with cowboys even offering meals of antelope steak, coffee, onions, and bread out of their chuck wagons to the settlers. Rabbi Wise was optimistic, writing in October 1882 that “by next spring, we hope to see the colony augmented to 500 souls if our friends will continue to give us their kind support.”

The same year, several other farming settlements were established by and for Russian Jews in the Western United States. In Cotopaxi, Colorado, 63 immigrants were settled by the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, financed in part by Emmanuel H. Saltiel, a Jewish businessman who had purchased land in the area. Saltiel apparently overstated the land’s suitability for farming. Colonists who expected to find established wells and roads were instead welcomed by mountainside land nearly 7,000 feet above sea level. Another settlement, Weschler Colony, was established 20 miles from Bismark in the North Dakota Territory and funded by London’s Mansion House philanthropy. Still another group of colonists made the month-long steamer voyage to Portland, Oregon, from New York to found a community in the Pacific Northwest. Jews were not the only ones seeking independence, opportunity, and farmland in the Western United States: Five years earlier, former slaves known as Exodusters homesteaded the all-black settlement of Nicodemus, Kansas, 160 miles north of Beersheba.

After Beersheba’s initial success, disputes erupted between community members and administrator Joseph Baum, a Hungarian-born Jew appointed by Rabbi Wise and the agricultural society. The conflict came to a head in 1884 when settlers began to explore other enterprises, including leasing part of their properties to cattle herders. In retribution, Wise and the agricultural society abruptly recalled the livestock and farming implements that they had supplied to the offenders.

Received of (Rabbi) Moses Edelhertz … one pair of oxen, two cows, one calf, one wagon, one yoke, one chain, one well bucket and yoke, axe, shovel and churn, twelve milk pails, two milk buckets, hatchet, wheelbarrow, 1 pair boots, one straw hat, one bail of wire.

—T.J. Patterson, Constable, April 9, 1884

Shortly thereafter, Beersheba colonists began dispersing and seeking their fortunes elsewhere, operating meat markets and dry goods stores in nearby boomtowns of Eminence and Ravanna and further afield in Garden City, Dodge City, and Wichita.

At least half of the residents remained long enough to claim ownership of their 160-acre parcels and on May 24, 1887, nine colonists filed their intent for U.S. citizenship. Several of the new land owners quickly mortgaged their properties for $200 each to fund future enterprises.

As for the cornfield cemetery in present-day Sherlock Township, the oldest stone is engraved in both Hebrew and English and belongs to Prussian-born Sara Ochs Teitelbaum (1849-1884). In 1880, Sara was living with her Hungarian-born husband, Samuel, and their young sons Bennie and Milton in Indiana, where Samuel worked as a merchant. Samuel had sailed from Hamburg to the U.S. in 1864 and, unlike many of the other Beersheba colonists, was already a naturalized citizen by 1873. Perhaps motivated by land ownership, the young family relocated from Indiana to Beersheba where daughter Hattie joined the family. In 1884, 35-year-old Sarah died (perhaps in childbirth) and the cemetery was established. The following year’s census identifies her widower, Samuel, still living on the farm with their three children. Eventually, Samuel remarried and moved to the East Coast, leaving for Jerusalem in 1903.

Three years after Sarah’s passing, 42-year-old C. M. Sternberger (1845-1887) died, possibly of tuberculosis, and was buried near Teitelbaum, although his gravestone is now barely visible. Sternberger was apparently already homesteading in Montgomery County, Kansas, in 1870.

The other visible stone in the cemetery belongs to Lieb Toper (1829-1933) and his wife, Goldie (1851-1921). Toper (originally named Laza Dansky and born in Russia) and Goldie arrived in the Beersheba area in 1887, homesteading before moving to nearby Garden City to run a business. In 1921, at age 72, Goldie died and her husband conducted her funeral in Yiddish. Lieb continued to reside in Garden City until age 104, and is interred beside his wife.

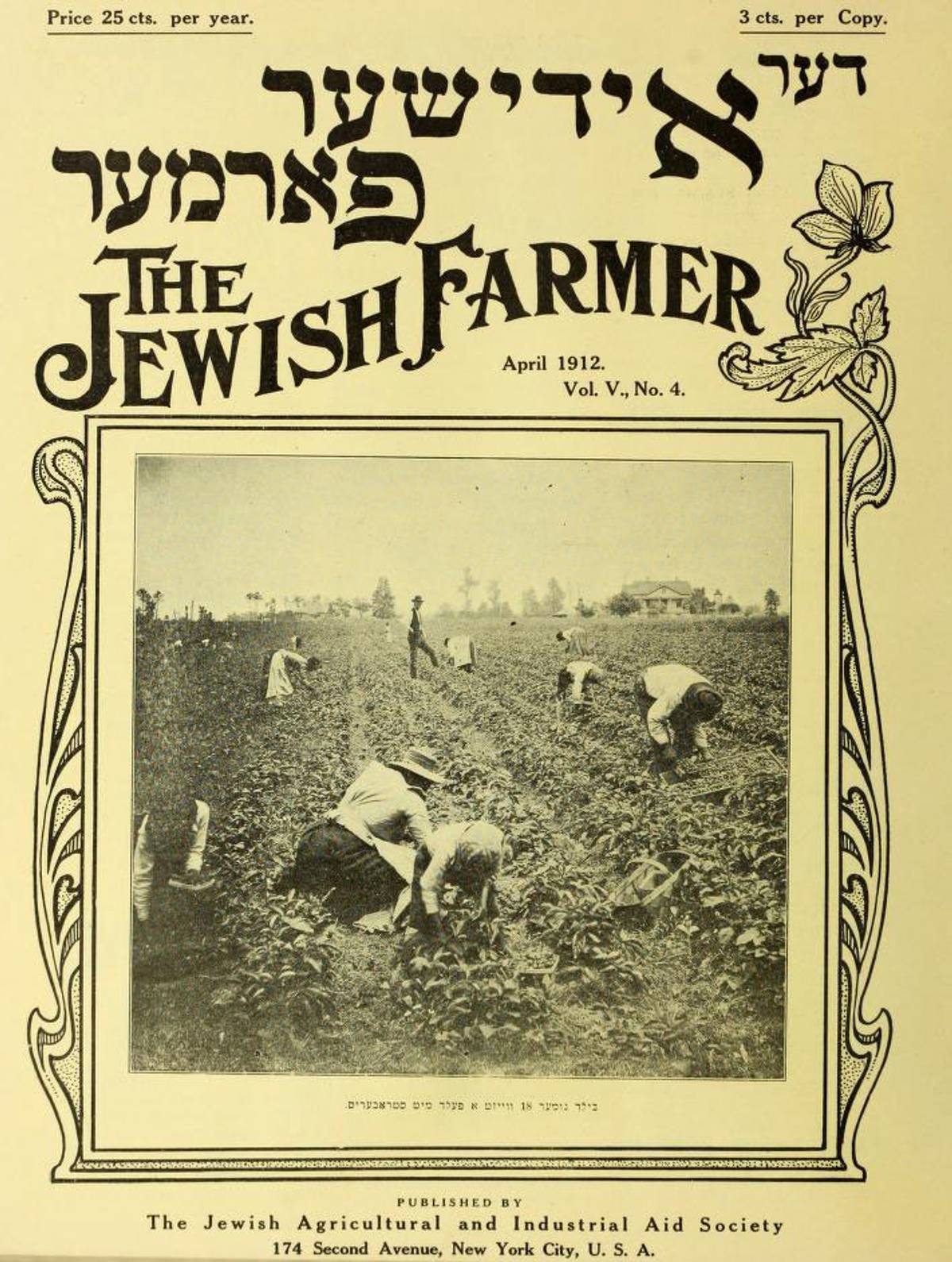

The Beersheba colony ended completely by 1887, five years after the experiment had begun. However, the demise of Beersheba was not the end of the Jewish agricultural experiment. Six additional Jewish farming communities were established in Kansas between 1883 and 1890 but were short-lived due to poorly selected locations or dreadful weather conditions. In 1900, the Baron de Hirsch Fund launched the Jewish Agricultural Society to train and finance would-be Jewish farmers in the Americas. The society published a Yiddish-English periodical, The Jewish Farmer, which provided technical advice, sponsored conventions and scholarships, and placed Jewish men as farmhands. By 1909, the society counted over 3,000 Jewish farm families—15,000 individuals—in 37 U.S. states. Both WWI and the development of other means of financing agricultural activities slowed the rate of the society’s activities.

As for the Beersheba colonists, the community was a springboard for other American dreams. After meeting in Beersheba, where their fathers were both homesteaders, Moses Cohn, 24, and Emma Ittelson, 18, were married by Rabbi Edelhertz in 1887. Their first daughter was born in nearby Ravanna the next year. By 1900, the Cohns, their five children, and Ittelson in-laws relocated to Carbondale and Denver, Colorado, where they homesteaded long enough to obtain an additional parcel of 160 acres. The family eventually settled in St. Louis, where Moses became a prominent curtain manufacturer and real estate investor, providing numerous jobs in the community. The couple’s children and grandchildren were well-supported and well-educated. When Moses Cohn died in 1949 at age 83, his estate was worth $376,000 and included bequests to the Jewish National Fund and other Jewish organizations. Isaac Mayer Wise’s essential question, “Will they become good citizens of this country?” appears to have been answered.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Naomi Sandweiss is the author of Jewish Albuquerque, and a past president of the New Mexico Jewish Historical Society.