Slaughterhouse Shrive

In this week’s ‘Daf Yomi,’ Talmudic rabbis debate who is free to butcher animals piously according to Jewish ritual. Plus: the one transgression that is unforgivable under the Torah.

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

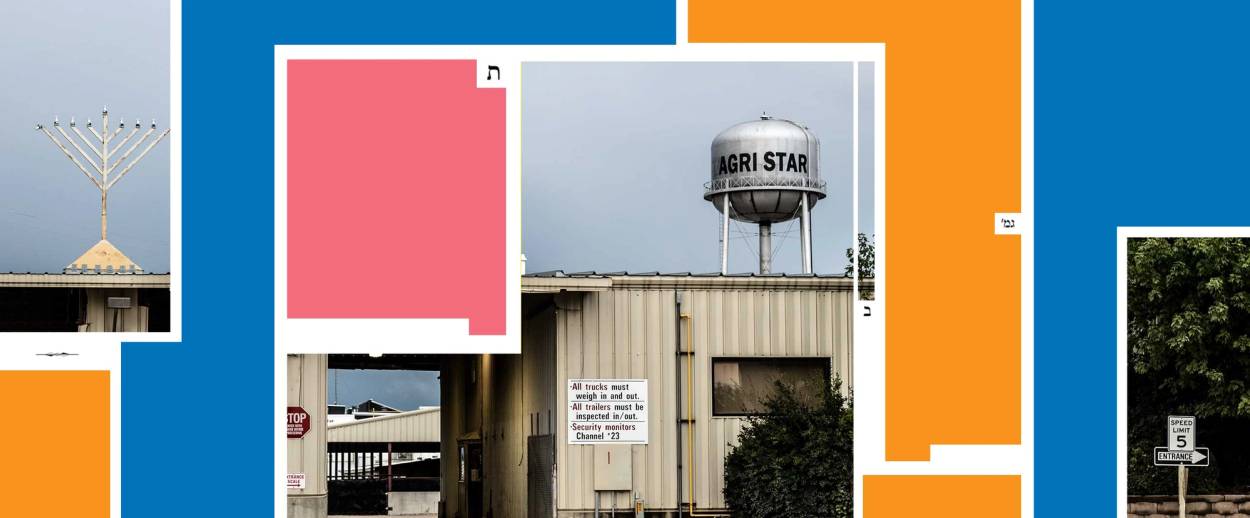

This week, Daf Yomi readers began Tractate Hullin, the third tractate in the division of the Talmud called Kodashim, or “sacred things.” Yet the word “hullin” means “profane,” and the subject of the tractate is the slaughter of non-sacred animals—that is, animals that are killed in order to be eaten, rather than to be sacrificed in Jerusalem. Why, then, does this tractate belong in Seder Kodashim, which is primarily concerned with Temple matters? The introduction to the Koren Talmud’s volume gives a twofold explanation. First, the rules for killing a nonsacred animal are parallel to those for killing a sacred animal. Second, and more interestingly, the placement of the tractate suggests that there is an element of holiness in all Jewish slaughter, whether the animal is destined for the altar or the butcher shop. By imposing specific rules on slaughter, Halacha weaves it into the fabric of Jewish law and life.

Kosher slaughter is such a fundamental part of Jewish practice that one might think it is taught in the Torah. But it isn’t: God often commands the Israelites to slaughter animals, but without specifying the tools or methods to be used. The rules elaborated in Hullin, then, are part of the Oral Law, based on traditional Jewish practice. In Hullin 4a, the Gemara explains that there are five basic actions that disqualify a slaughter: “interrupting, pressing, concealing, diverting, and ripping.” A kosher slaughterer must not interrupt the act of cutting the animal’s throat once it has begun, but use one continuous motion. He must not press the knife into the animal’s flesh, but cut with a back-and-forth, sawing movement. He must not “conceal” the knife by plunging it into the animal’s flesh, but sever the windpipe and gullet from the outside. He must not divert the knife from the place where the initial cut is made, but only deepen that first cut. And he must not rip the windpipe or gullet out of the animal’s neck, but cut them while they are still inside its body.

Typically, however, the Talmud does not set out these rules formally, in order to explain their logic or justification. Rather, the rabbis refer to them in passing, on the assumption that they will already be known to the student. The Talmud approaches the subject of slaughter by means of specific questions and problems—specifically, in these first pages, the question of who is permitted to slaughter an animal in the first place. We already learned, back in Tractate Zevachim, that while most of the Temple rituals connected to animal sacrifice have to be carried out by priests, the actual slaughter does not.

That principle is confirmed in the mishna in Hullin 2a, which states, “Everyone slaughters and their slaughter is valid.” This specifically includes women, although in practice Jewish women have been barred from acting as slaughterers. The only categories of people who cannot perform kosher slaughter are “a deaf-mute, an imbecile, and a minor”—in other words, people who are presumed to be physically incapable of carrying out the process correctly. But even then, the mishna concludes with a qualification: “And for all of them, when they slaughtered and others see and supervise them, their slaughter is valid.”

Read straightforwardly, it would seem that this proviso applies to the aforementioned categories of deaf-mute, imbecile and minor. In other words, even those people can perform a kosher slaughter so long as they are being supervised, so that they will do things the right way. But the Gemara makes an argument, on grammatical grounds, that the proviso is not actually meant to apply to deaf-mutes, imbeciles and minors. Instead, various rabbis try to apply it to other types of people whose slaughter might appear halachically suspect. First, it is suggested that the person who requires supervision is one who slaughters an animal for sacrifice while he is in a state of ritual impurity. The concern here is that if he touches the meat, he will transmit tumah and render it invalid for the altar. But no, the Gemara replies: In this case, supervision is unnecessary. As long as the slaughterer can testify that he did not touch the meat, his word is accepted and the slaughter is valid.

Abaye proposes that the person who requires supervision is a Samaritan, in Talmudic language a Kuti. The Talmud frequently worries about whether the Samaritans, who claimed to follow Jewish law, are in fact authentically Jewish and can be trusted to carry out mitzvot properly. According to the Talmud’s understanding, they are not Jewish, because they are descended from alien peoples who were imported to the territory of Samaria after it was conquered by the Assyrians in 722 BCE. The only reason they claim to follow Jewish law is because, as the Book of Kings relates, God sent lions to terrorize them into obedience. (This official hostility to the Samaritans is what gives force to the famous parable of the Good Samaritan from the New Testament.)

Can a Samaritan perform a valid slaughter under Jewish supervision? The rabbis debate the issue, with some saying that a Jew must be continually present during the whole slaughter, while other think it’s sufficient for a Jew to “enter and exit,” that is, look in on the process occasionally. If there’s some doubt as to whether a Samaritan has slaughtered properly, the test is to see whether he himself will eat an olive-bulk’s worth of the meat: If he will, a Jew can trust that the slaughter is valid. That is because, according to Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel, “with regard to any mitzva that the Samaritans embraced, they are more exacting in its observance than Jews.” This unexpected compliment suggests that while the Samaritans didn’t understand Jewish law in just the same way as the rabbis, they were zealous in following the law as they did understand it.

The Gemara goes on to ask whether a Jew who violates the law in other respects can be trusted to follow it when it comes to slaughter. “This transgressor, what are the circumstances?” ask the rabbis in Hullin 4b. In other words, it all depends on which laws he violates and why. Take someone who is so hungry that he eats meat from an unslaughtered animal carcass. This is a major dietary violation, but does it follow that such a man would violate the laws of slaughter even when he doesn’t have to? The Gemara says no: “A transgressor would not intentionally forsake the permitted manner and eat food in a prohibited manner,” at least not when he has the choice of slaughtering correctly.

When it comes to other types of transgressors, the question becomes trickier. What about a Jewish man who is uncircumcised? If he did not undergo circumcision for medical reasons—as the rabbis say, maybe other boys in his family died from the operation, so his parents refused to submit him to it—he is not culpable. But what if he simply refused to be circumcised out of sheer contrariness? Even in this case, the Gemara says, his slaughter can be trusted. That is because “a transgressor concerning one matter is not a transgressor concerning the entire Torah.”

There is only one exception to this lenient rule: “A transgressor with regard to idol worship is a transgressor with regard to the entire Torah.” An idol worshipper rejects Judaism so fundamentally that he can’t be trusted to carry out any of its laws, including the laws of slaughter. When we remember the violent language the rabbis used about idol worshipers back in Tractate Avodah Zarah, it comes as no surprise that they don’t want such people anywhere a Jewish ritual.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.