Rise of the Machines

A traveling museum show introduces new audiences to cartoonist and silly-machine inventor Rube Goldberg

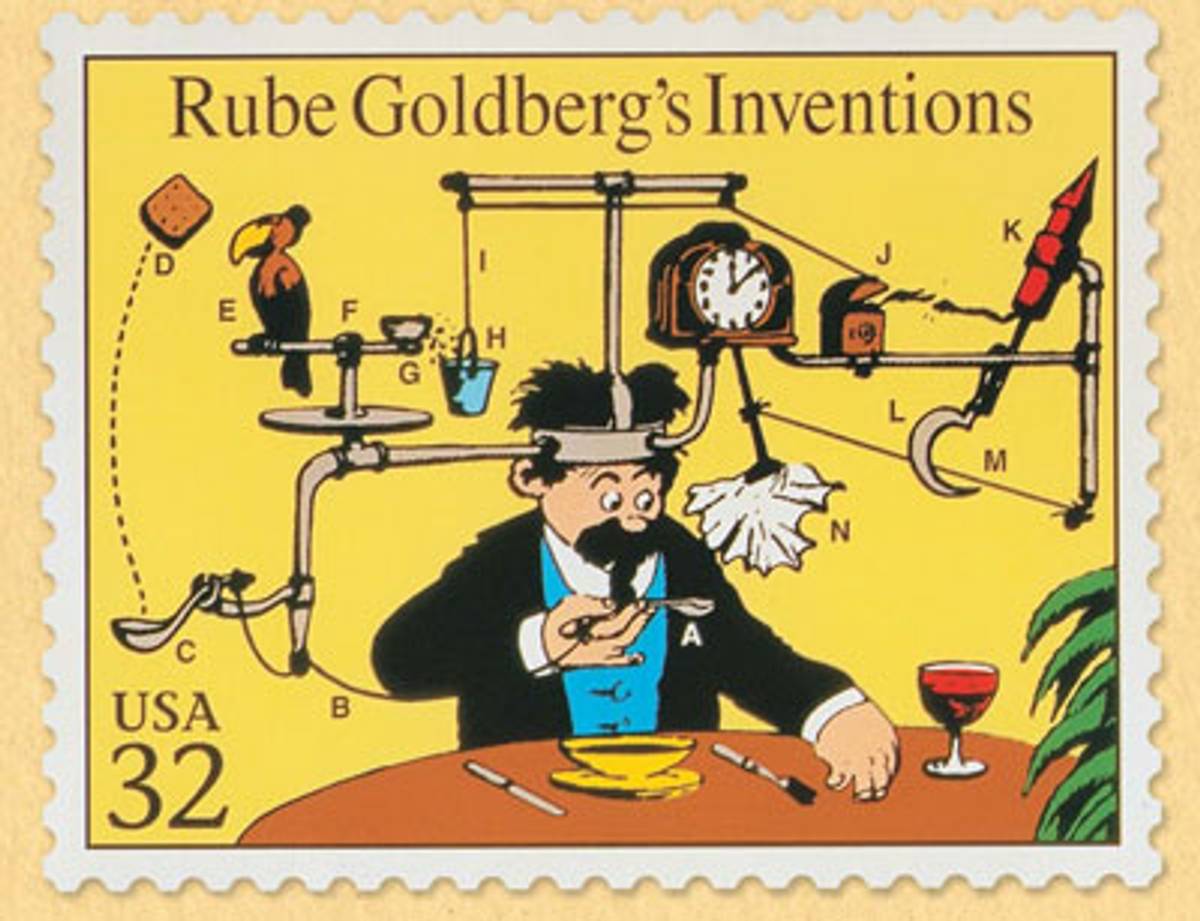

Rube Goldberg’s name is synonymous with silliness. This is not a metaphor. In 1931, “Rube Goldberg” was added to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary as an adjective, meaning “accomplishing by complex means what seemingly could be done simply.” On exhibit at the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia until Jan. 21, The Art of Rube Goldberg offers visitors a delightful look inside the world of the cartoonist and fantasy-machine inventor. (A more kid-centric and interactive version of the show is at the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh through May 5.)

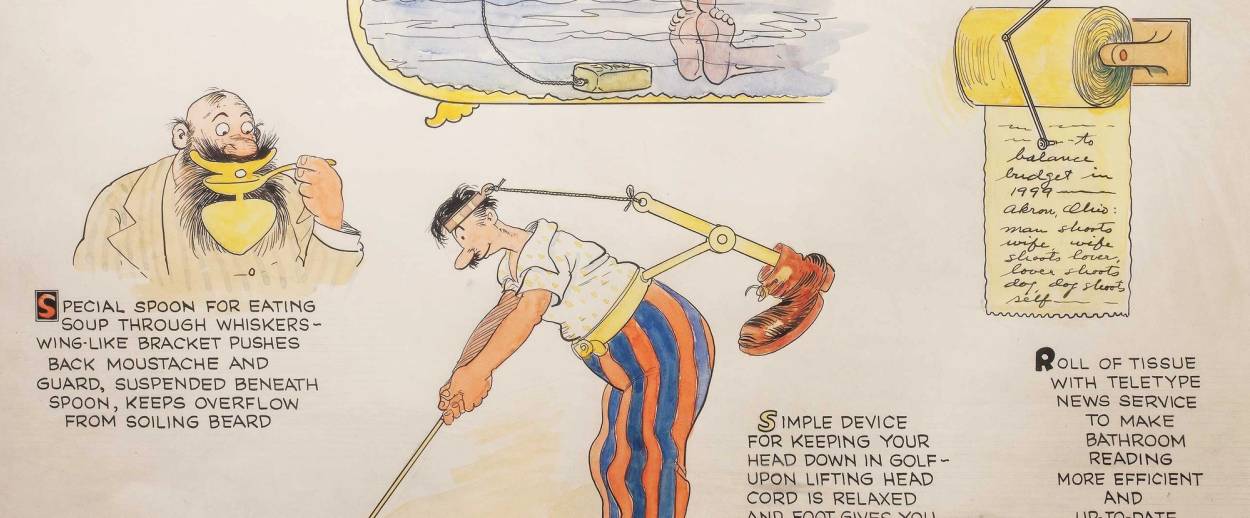

Goldberg, who died in 1970, is most famous for his “machine drawings” depicting a wacky and complicated chain of events designed to solve a minor problem. One of the cartoons in the NMAJH show, for example, depicts an Automatic Women’s Hat Remover for Use at the Movies. In the illustration, a seething man sits behind a woman whose fancy chapeau blocks his view of the screen. Clipped to the back of the man’s seat is a giant, elaborate contraption designed to solve such a problem. The text reads: “As you burn with indignation, fumes (a) melt wax (b) causing scissors (c) to cut string (d). Weight (e) falls and pulls out stick (f), allowing alligator (g) to bite off hat (h), clearing visibility.” An addendum notes, “P.S. Usher immediately removes apparatus so man in back of you can see, too.” Easy peasy!

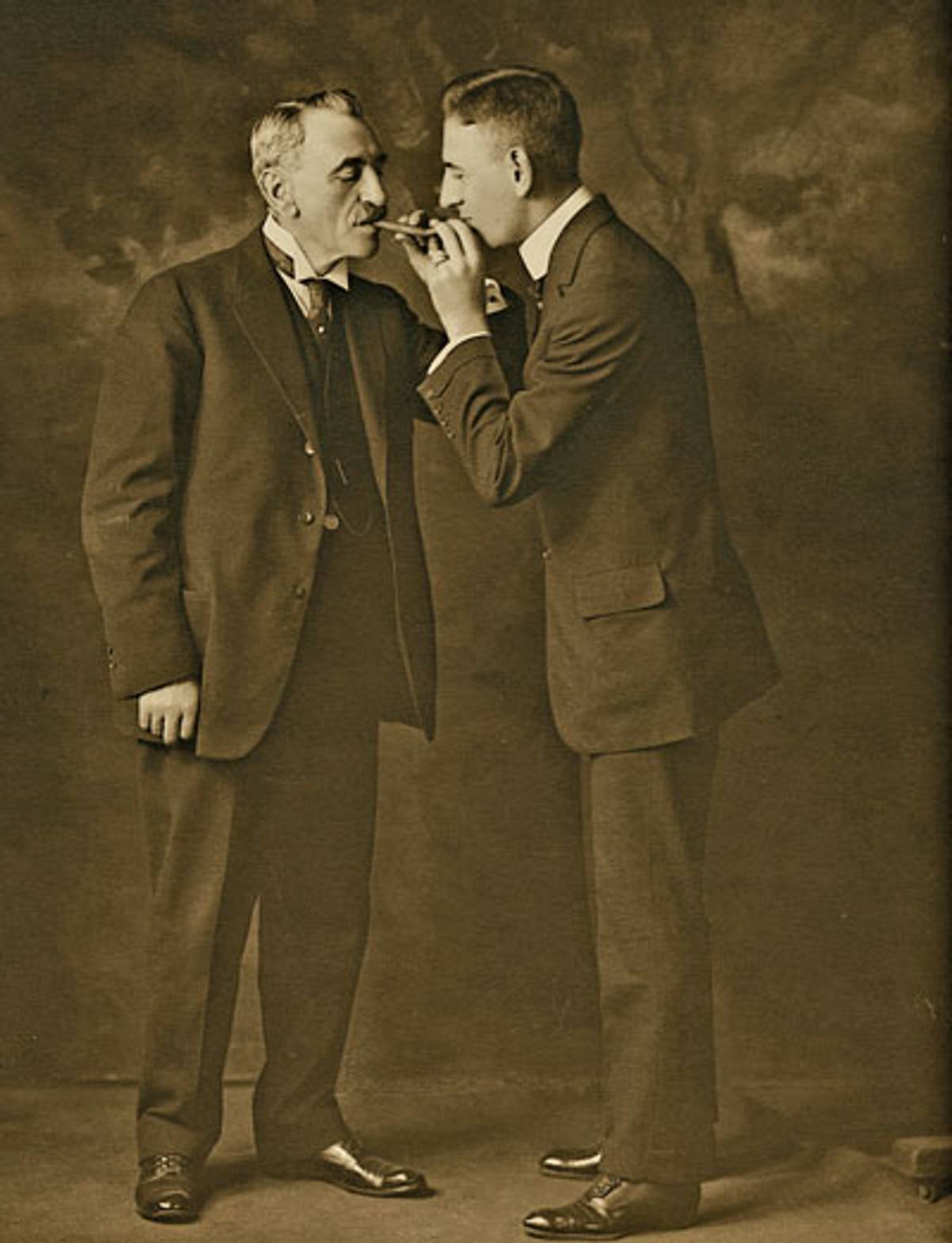

The show leads viewers through the cartoonist’s 72-year career, which encompassed not just machine drawings but also newspaper comics, humor books, games, building kits, print ads, and Pulitzer Prize-winning editorial cartoons. (Goldberg was a master of reinvention.) There’s a video of inventions Goldberg designed for Charlie Chaplin and the Marx Brothers, and an entertaining roundup of clips of Goldbergian machine inventions in pop culture: Pee-wee Herman gadgets, OK Go music videos, and the opening scene of Back to the Future. Viewers can admire photos of Goldberg and his beautiful wife, Irma, at glamorous soirees—they partied hard with New York City Mayor Jimmy Walker during Prohibition and rang in the New Year with George Gershwin, Groucho Marx, and a glam apartment full of men in tuxes and women in jewels, slinky satin, and furs. “The Roaring Twenties took place in my grandparents’ living room,” Goldberg’s granddaughter said.

This is the first large-scale retrospective of Goldberg’s work since 1970, and contains works that haven’t been shown before, as well as a STEM-flavored, candy-colored design studio that lets young visitors create their own Rube-esque inventions using pool noodles, marbles, pipe cleaners, binder clips, toy train tracks, plastic fruit, cups, spools, and string.

*

Reuben Garrett Lucius Goldberg was born in 1883 in San Francisco to immigrants Max and Hannah Goldberg. He was the third child of seven. His only formal art training was taking drawing lessons from a local sign painter when he was a kid. He always wanted to be an illustrator, but his father insisted he pursue something practical and economically dependable. (Just like the father of Leonard Bernstein, subject of the museum’s retrospective before Rube.) Goldberg studied engineering at UC Berkeley, where he drew for The Pelican, Berkeley’s humor magazine, and got a job with the San Francisco sewer system when he graduated in 1904.

He lasted a year. Taking a huge pay cut, he became a sports cartoonist for the San Francisco Chronicle. In 1907, he decamped for New York City—which he called “the front row,” the center of the cartooning world—in 1907.

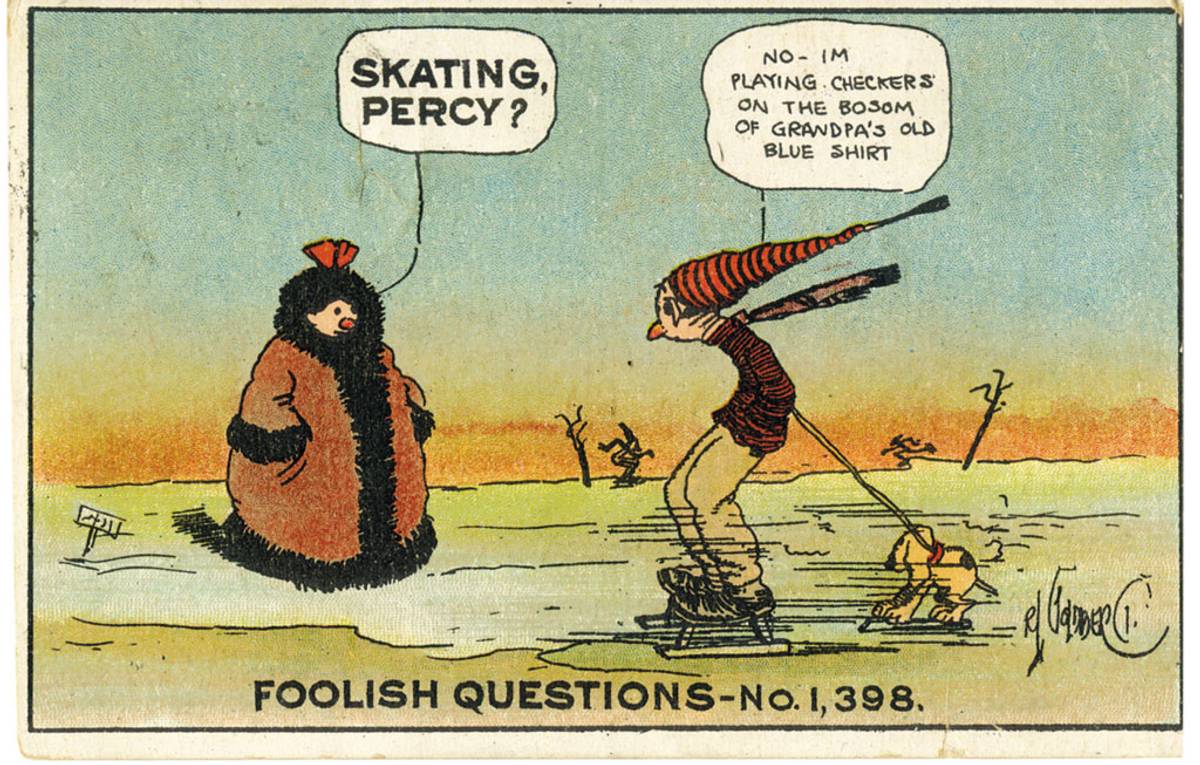

He soon created a series of popular comic strips: “Mike & Ike” (identical twins, but one was Irish and the other Jewish), the bearded and incompetent “Boob McNutt,” and “Foolish Questions,” a series of snarky, vaudeville-inflected jokes inspired by the saying, “Ask a foolish question, get a foolish answer.” (Goldberg briefly performed in vaudeville himself.) “Foolish Questions” debuted in 1908 in the New York Evening Mail and was an instant smash. People sent in their own suggestions based on actual encounters they’d had with idiots. Examples in the show: A wife asks her husband, who has just cut himself shaving, “O Dearie, did you cut yourself?” He replies, “No, my little hummingbird, I fell asleep on a buzz saw.” A boy asks a girl picking flowers in a field, “Pickin’ flowers, Lucy?” She answers, “No, you simple-minded piece of cream cheese—I’m filling our coal shutter with applesauce.” A father asks his pipe-smoking son, “Son, are you smoking that pipe again?” The son answers, “No, dad, this is a portable kitchenette and I’m frying a smelt for dinner.” An early master of merchandising, Goldberg parlayed the series into a book and a card game. He also created Boob McNutt-branded “Lucky Bucks Play Money,” turned other cartoons into ashtray designs, and wrote a series of 24 “Mike & Ike” short films released by Universal Studios.

In 1922, Goldberg signed a syndication contract that earned him a then-astronomical $200,000 a year, worth nearly $3 million today. He devoted a series of cartoons to Irma (the heiress to the White Rose grocery fortune!) and her ladies-who-lunch crowd. The women in Goldberg’s affectionate drawings wear spectacular plumed hats and curvy-heeled shoes (Goldberg was very observant about fashion) and engage in self-bettering pursuits such as hiring “one of those cake-eating poets” to read verse that “makes you feel very intellectual because you can’t understand it.” A skinny poet, in floppy bow tie and thick glasses, intones,

Awake, awake, the dawn is here,

the little apples are happy in the

thought that they will soon grow

up to be apple-sauce;

Yonder cheese lifts its head and

wafts its perfume towards the sunbeam:

O, herring, prince of fish, beware of

thine enemy, the delicatessen man –

How beautiful is love.

A slightly Goth-looking society babe with a tiny black hat, black shawl, black bob, and a lot of mascara gasps, “Gorgeous!” A more conventional looking matron observes, “It doesn’t rhyme and there’s no sense to it—it must be wonderful poetry!”

Some of Goldberg’s sexism and ableism (there’s a herky-jerky old cartoon in the show that mocks both husband-hungry ugly women and blind men) haven’t aged well. But hey, when you’re superprolific and your work spans multiple decades, you’re not gonna produce only gems.

Goldberg’s creativity seemed infinite; he drew over 50,000 cartoons. His invention drawings began in 1912 and continued for decades. “You can really see the engineer’s mind at play,” Dr. Josh Perelman, NMAJH’s chief curator, told Tablet of this part of the show. “The taxonomy of the chain of ideas, the cognizance of cause and effect.” Goldberg’s patent-style drawings reflect the growing role of technology and automation in Goldberg’s lifetime. “He watched the industrial revolution happen,” Perelman said. “He witnessed the rise of mass production and mass consumption, and he commented on it with these Dadaist inventions.”

Goldberg’s pundit, Deepdish Sachel (Yiddish for “wisdom”) The Third, informs the reader, “In the post-war world, everybody will have everything: Air-conditioning, refrigeration, vitamin-loaded meals, super-education, automatic necking, portable sunshine, and minimum exertion. This will make it practically impossible to find a President who worked his way up from a miserable log cabin with no heat, no light, no books, and no food. But that will be all right, because it will force the campaign orators to change that same speech they’ve been making for the last hundred years.” Plus ça change.

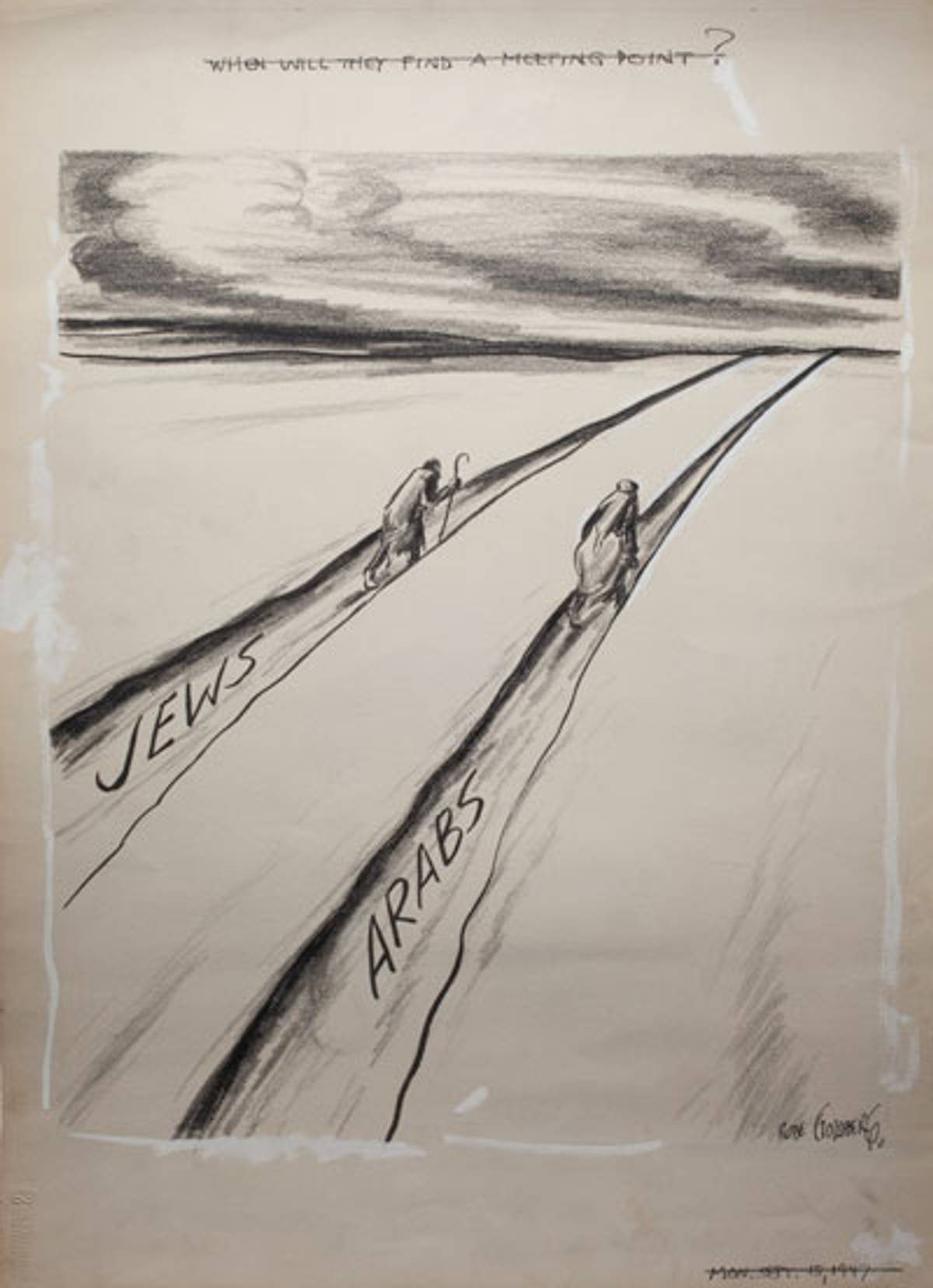

In 1938, at the age of 55, Goldberg pulled a 180 and became a serious political cartoonist. His style at The New York Sun, where he did three cartoons a week on subjects of his choosing, became simpler and bolder. In 1948, he won the Pulitzer for “Peace Today,” depicting a little house and yard, a grill, an outdoor umbrella, and a dog … all balanced atop an atomic bomb dangling over an abyss labeled “world destruction.” To Goldberg, technological advancements were marvelous and mockable, until they weren’t.

Another cartoon, published in 1947, depicted a Jew and an Arab walking in parallel wadis in the desert that lead all the way to the horizon. “When will they find a meeting point?” the text asks. We’re still asking.

Goldberg continued to do editorial cartoons until he was 80. One of the last works in the show is his 1967 cover for Forbes Magazine, illustrating a story called “After Color TV? The Future of Home Entertainment.” A family sits together but apart in the living room, each in their own world, watching their own device. Dad has a box on his lap that projects a horse race onto the living room ceiling; Mom watches skiing on a cube attached to a globe; a teenage daughter stares at a long-haired rock band projected on another wall; a little boy with an antenna on his head watches a puppet show. Even the cat watches another cat in a tiny box. “Rube even foreshadowed cat videos!” Perelman said.

Rube’s automated visions continue today, via the annual National Rube Goldberg Machine Contest, established in 1987. Teams compete to build elaborate devices to solve simple problems like putting a stamp on an envelope, making a cup of coffee, or putting a penny in a piggy bank. In 2005, a team won with a machine that required 125 steps to turn on a flashlight. Last year, at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, the Purdue Society of Professional Engineers won with a contraption that took 3,300 hours to build, consisting of three huge rotating medieval-themed dioramas, that culminated in the pouring of a box of Lucky Charms into a bowl.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.