Time Regained

In a Polish prisoner’s lectures on Proust and a Jewish Holocaust survivor’s defiant Hebrew calendar, lessons in resilience and survival

In 1924, Józef Czapski left Krakow and settled in a small apartment in Paris. His aristocratic family’s estates were all seized by the newly ascendant Soviets, which freed the young man to pursue his true passion, painting. With nothing to lose, he spent his days working and befriending the city’s sophisticates, who soon insisted he devote himself to the work of a recently deceased wonder boy, one Marcel Proust. Czapski picked up the first volume of Proust’s monumental novel, read a few pages, and put it down. The book, he felt, was much too stylized, intolerably French, its thicket of run-on sentences too dense for any sensible soul to find its way through. A year later, recovering from ailments both real and romantic, Czapski gave Proust another try. And Proust, as he always does if you only let him, changed the Polish painter’s life.

Just how deeply Proust had affected Czapski was evident decades later, when the Pole was arrested by the Russians and sent to the gulag. There, frozen but unbroken, the nobleman convinced his captors to permit the prisoners to lecture each other on subjects close to their hearts. Czapski, naturally, chose to speak about his favorite author, and his lectures, collected under the unimprovable title Lost Time, were published last month by The New York Review of Books.

They are, for many reasons, an astonishing read. Most viscerally and immediately, they deliver the pleasure of witnessing Czapski, standing in a bare barrack without a single printed volume at his disposal, delivering erudite talks that not only recall entire sections of Proust’s novel by heart but also provide valuable insights into what makes the 4,215-page work a territory so many of us continue to visit so frequently and with so much reverence. “Proust’s interconnections are immensely divergent,” Czapski informed his fellow prisoners, “drawn from all times, from all the arts, so that Proust’s pages became much more an account of his own thoughts awakened by a collision with a fact, rather than just the facts themselves.”

But Proust proved more than just a pleasurable distraction. He was the herald of one big idea, a radical concept the incarcerated men fashioned first into a banner and then into a weapon, an understanding so profound it all but guaranteed their survival. It was, quite literally, about time.

Following his relative, the philosopher Henri Bergson, Proust took issue with our notion of time as a linear progression of units that can be easily and exactly measured. What, really, is a day to us? A week? A year? Our experience of time refuses these arbitrary categories, forming instead something Bergson called “duration,” a qualitative alternative to the tyranny of the clock. In real life, he argued, a moment can be sped up or slowed down; a minute spent making love isn’t the same as a minute lost idling on the dental hygienist’s chair. Try to capture the now, and you realize it’s already gone, never to return, yours to revisit only through dreams and memories and other acts of the imagination.

Proust turned this insight into a masterpiece, and Czapski found in Proust precisely the wisdom he needed for life in the gulag. A captive, he realized, survives only if he succeeds in forging the jailer’s prison sentence—a set and harsh punishment—into a duration of his own, defiantly defined by tender and hopeful moments that no guard can take away. Outside, it might’ve been a subarctic hellscape, but as long as Czapski and his friends could stop Soviet time and replace it with a few minutes of talking and thinking about Proust, if only for a little while, they were free.

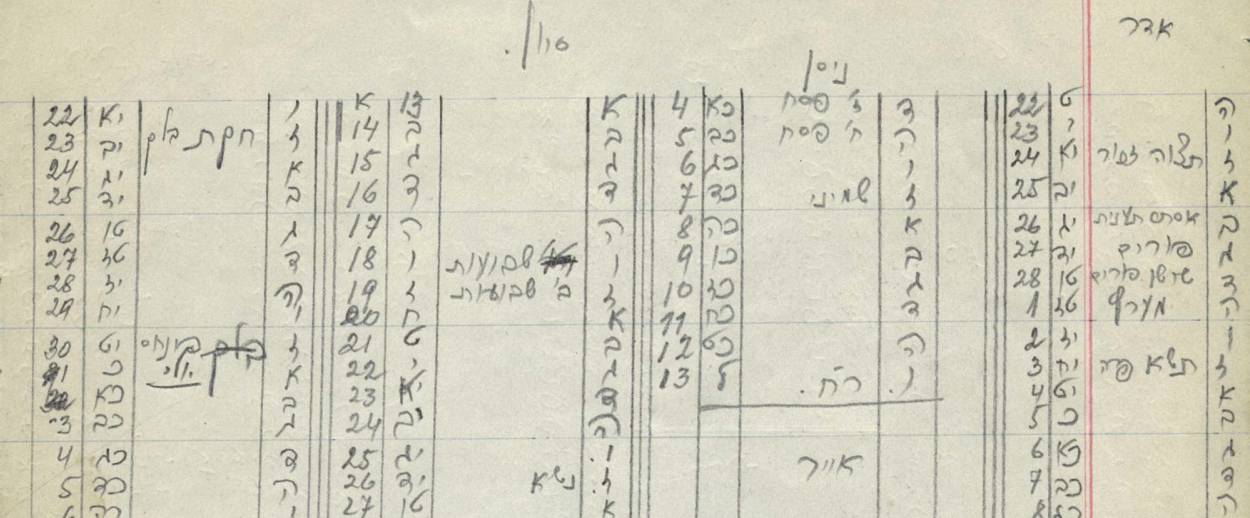

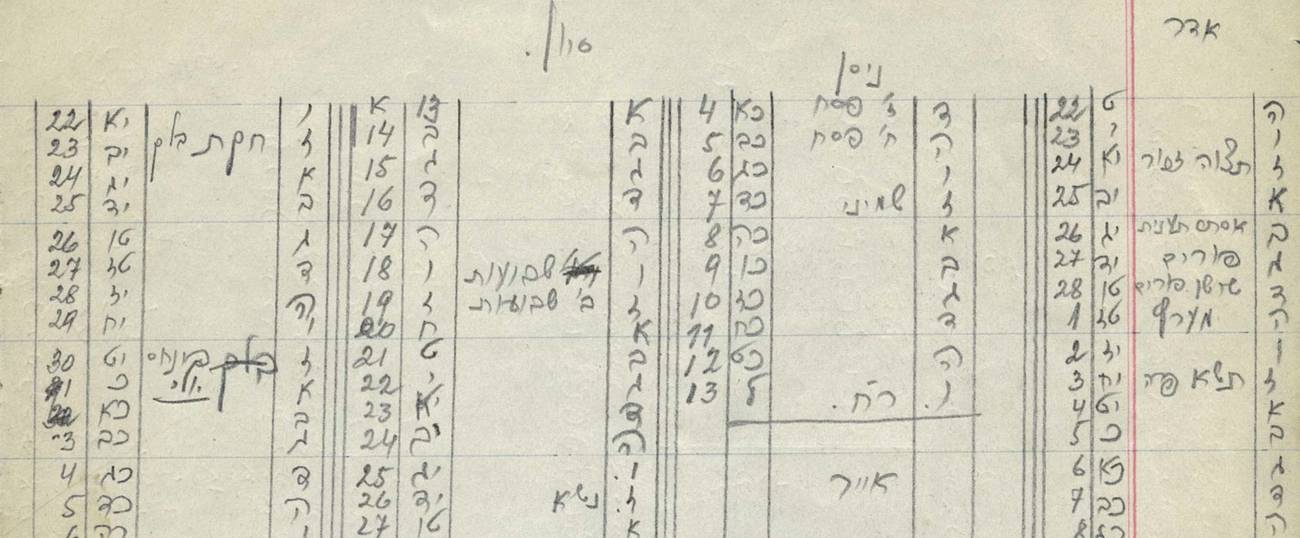

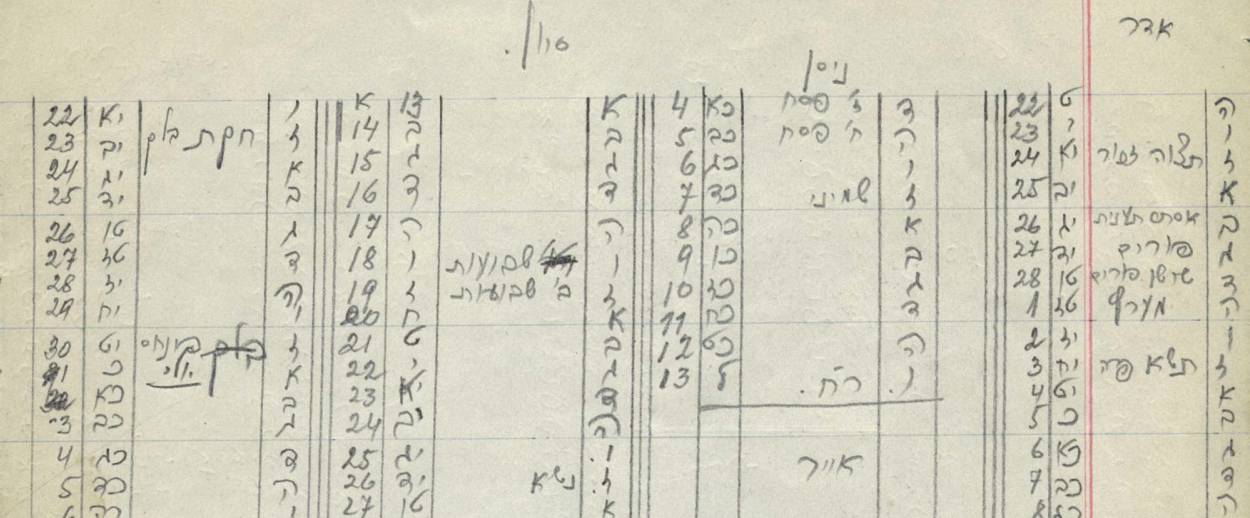

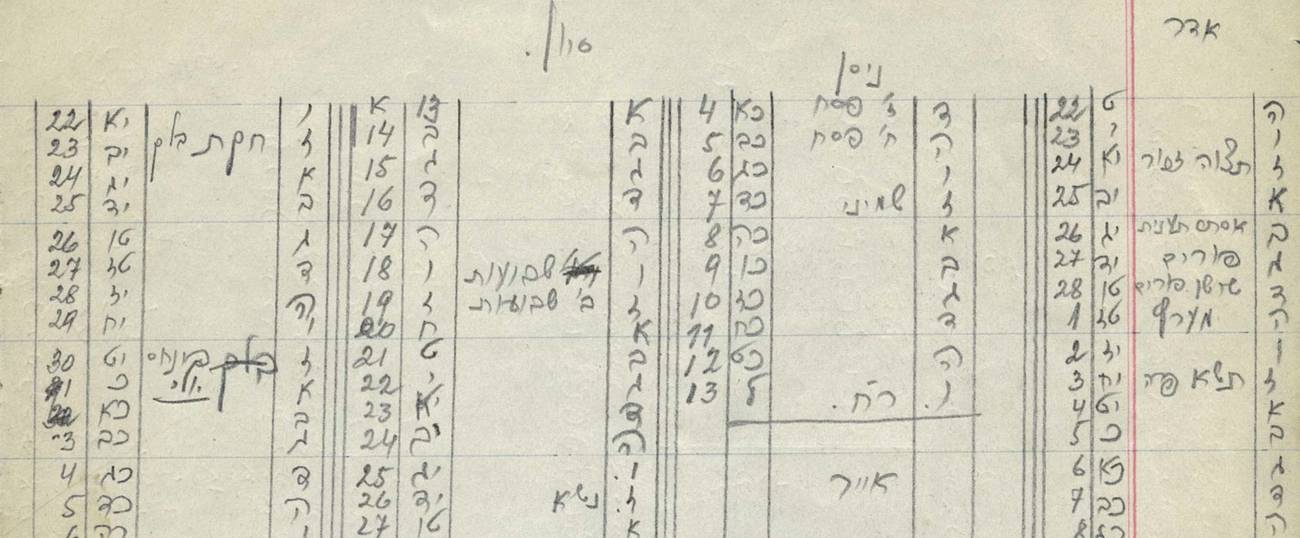

As it happened, I finished Czapski’s marvelous book before visiting Yad Vashem for a weeklong seminar. Day after day, I had the privilege of listening to the institution’s experts and scholars present their research, and was thrilled to sample its extensive collection of documents and artifacts. Many of them were eminently important, like the first existing blueprint of Auschwitz, and many were heartbreaking, like a pair of baby shoes that were the last thing two young Jews found when they returned to the ghetto from a day of forced labor and learned that their child, Hinda, was taken with the rest of the children and put to death. But the artifact that touched me the most wasn’t quite as seminal or as dramatic. It was, in fact, just one sheet of paper, a makeshift calendar noting the Hebrew months and weekly parshas.

It was written by Jacob Avigdor, a Polish-born rabbi who was deported to Buchenwald, where he lost his wife, his daughters, and his brothers. Losing neither his faith nor his will to live, he bartered away his meager daily ration for a sheet of paper and a stub of a pencil, and, working from memory, drew up his calendar, an offense punishable by death. But Avigdor was undeterred. His duration in Buchenwald, he knew, was his to shape, and instead of succumbing to the Nazis’ insistence that he see himself as no longer human, just a number in their arithmetic of death, he rebelled. He remembered Tishrei and Kislev and Av, mused on the biblical portions he knew so well, and found meaning in moments that were no less real for existing solely in the collective Jewish memory. He survived the camp, going on to serve as Mexico’s chief rabbi for many years. And he left behind a little sheet of paper, much humbler than Proust’s opus but a monument to the same invaluable message that has sustained so many of us through so much darkness, the cosmically comforting and inherently Jewish understanding that there’s nothing you can’t overcome if only you learn to keep your own time.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.