If there’s one thing the American Jewish community has in abundance, it’s critics. “There are no colors gloomy enough to paint too morbidly” the present condition of the Jews, notes one of their number. A “baleful fog of indifference hover[s] over Judaism,” chimes in another. The synagogues are empty, more “grand vacuum” than grand house of worship, and young people today are “loud in dress, louder in commonplace and empty words,” or, worse still, apt to be “atheists, agnostics, or nothingarians,” adds a third and then a fourth naysayer.

Sound familiar? You’ve heard it all before, I’m sure. Even so, it might come as a bit of a surprise to learn that every single one of these observations dates from the late 19th century.

Then, as now, securing the interest and loyalty of the younger, or “rising,” generation befuddled even the most thoughtful of American Jewish leaders. The “young Israelite of today lives in an atmosphere of restless inquiry,” observed Rabbi Gustav Gottheil in 1886. How are we to formulate “some comprehensive reasons for living the Jewish life” when the established verities no longer ring true?

Some of Gottheil’s colleagues threw up their hands and gave into despair, as the published proceedings of rabbinical conclaves and the editorial pages of American Jewish newspapers recount in vivid detail. Others rose to the challenge, developing a creative strategy that, more than a century or so later, continues to hold sway among a significant proportion of the population: the showcasing of sociability rather than worship as the primary form of affiliation.

The notion that associational rather than religious ties was what might bring young Jews together—and keep them coming back—fueled the creation of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (the “YMHA,” or the “Y”) and its sister organization, the Young Women’s Hebrew Association, in the waning years of the 19th century and the inaugural years of the 20th.

At first, some American Jews conceived of the YMHA as an alternative to the Young Men’s Christian Association, whose origins dated back to antebellum America. Often the only public place in town with a gymnasium, the YMCA attracted a growing number of American Jewish men eager to be physically fit, arousing concerns lest they be led astray once inside its Christian walls. One Jewish communal leader didn’t mince words: The YMCA, he said, was a “menace.”

Others thought of a Jewish Y in less defensive and more positive terms: as an opportunity for “developing the manhood of” American Jews, a place where, amid dignified conversation, chess matches, and rounds of calisthenics, they might find “something of their own”; a place where it mattered not a whit where one’s parents came from or what kind of Judaism they practiced; a place to be with your own kind.

The Y’s champions believed that highlighting Jewishness rather than Judaism was the best possible way to attract younger members of the community and keep them within the fold. Jacob Schiff, the Jewish community’s late 19th-century Maecenas, thrilled to the possibilities. “The YMHAs,” he declared, “are better missionaries than nine-tenths of the congregations.” Another fan agreed. The Y’s activities, especially its Grand Chanuka Celebration, he wrote in the pages of the Jewish Messenger of 1879, offered a “more effective and powerful sermon than synagogue or temple ever listened to.”

It didn’t take long, though, before the Y became mired in controversy, the recipient of “tirades” from rabbis who fretted lest the organization undermine the primacy of the synagogue, or, worse still, generate a vacuous, empty-headed kind of American Jew familiar with the latest fads or “novelties,” but woefully ignorant of Jewish history and tradition. The Y, hotly declared one of its detractors in 1881, is “Hebrew only in name and because its members are all of Jewish birth.”

How, then, to do better? To be more “true to its title”? To bear in mind that the “term ‘Hebrew’ means ‘Hebrew,’ and not athletic, terpsichorean, dramatic, etc.”? A number of communal leaders suggested the Y would be best served by providing more explicit forms of Jewish programming alongside its roster of bowling circles, glee clubs, theatricals, dances, exercise programs, and a singles group known as the Celibates. Why not offer classes in Hebrew language and literature? Develop a library of Jewish books. Add religious services, or, at the very least, offer some kind of inviting Friday night event. Still others suggested that members might undertake “missionary work” among the steadily growing immigrant populations of urban America, seeing to it that they became “citizens of the heart and not merely of residence.”

These suggestions gave rise, in turn, to another round of criticism, this time from those who, liking things just the way they were, didn’t cotton to the notion of the Y becoming a “Talmud School,” as one participant, wary of efforts to teach Hebrew or offer lectures in that ancient language, put it in the American Israelite of June 1881, urging the Y to stop promoting “Hebrew studies as the panacea for every communal ailment.”

Finding the Y at a stalemate, torn between Torah and Terpsichore—or, as the ever-astute and gimlet-eyed Mordecai M. Kaplan, one of American Jewry’s fiercest critics as well as its most imaginative thinker, bluntly put it, “fumbling in the dark”—a number of rabbis, Kaplan prominently among them, came up with an inventive alternative: the synagogue-center concept where the gym and the pool, the dances and the card games, would be brought into the precincts of the synagogue. Expanding the latter’s purview, as well as its footprint, it allowed for what we today might call a more “holistic” or “synergistic” approach to modern Jewish life, one in which secular and religious pursuits lived side by side and under the same roof—as kin, not tenants.

The “shul with a pool,” as David Kaufman’s book of the same name richly documents, caught on, especially among the clergy, who took with gusto to the prospect of “synagogiz[ing] the tone of the secular activities.” Their hope was that a steady complement of fun and games alongside the customary cradle-to-grave responsibilities of a traditional house of worship would attract American Jews who might not otherwise step over its threshold.

A grand idea in theory, a win-win for all, but did it work in practice? A number of influential rabbis, among them Israel Goldstein of New York’s B’nai Jeshurun, had their doubts and soon soured on its ongoing viability. “Card parties and fat reducing exercises under Synagogue auspices have not made people more Synagogue-minded or even more Jewish conscious,” he glumly informed his rabbinic colleagues in 1928, at a time when synagogue centers throughout the country, in Brooklyn and Boston, Cleveland, and Newark, were all the rage.“The Synagogue as a week-end institution may have seemed aloof and ineffective. As a week-day institution, functioning through the Center, it has become banal, and even vulgar.”

Ultimately, it wasn’t criticism or even competition from the Y, whose imprint on the urban landscape remained strong, that did in the synagogue-center as much as demography. A one-generation phenomenon and an exclusively urban one, at that, the synagogue-center fell prey, and ultimately succumbed, to the new realities of postwar America. A casualty of suburbanization, it also faced increasing competition from the Jewish community center, or JCC.

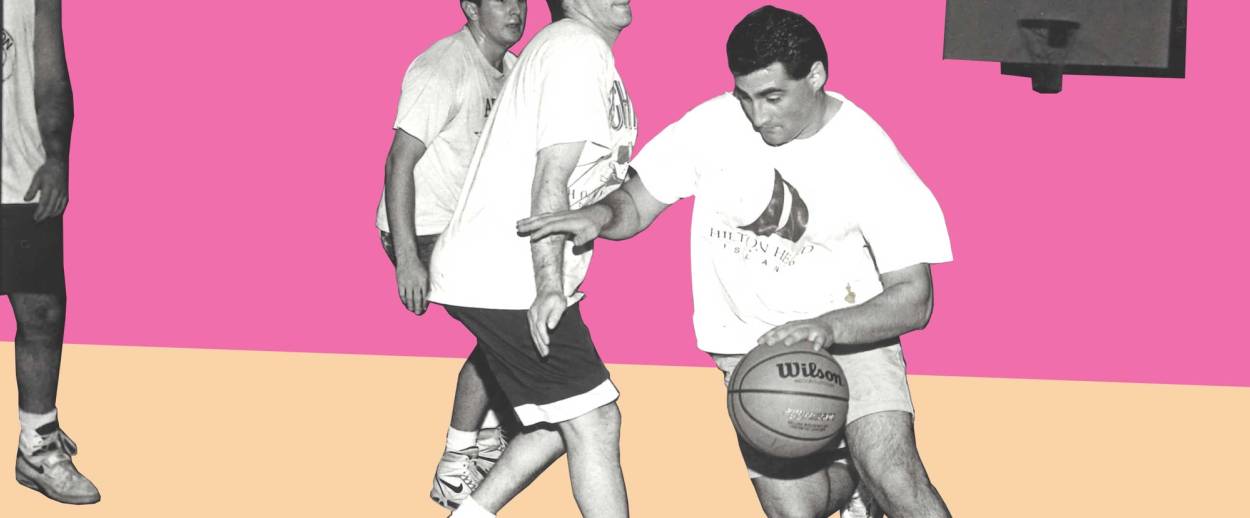

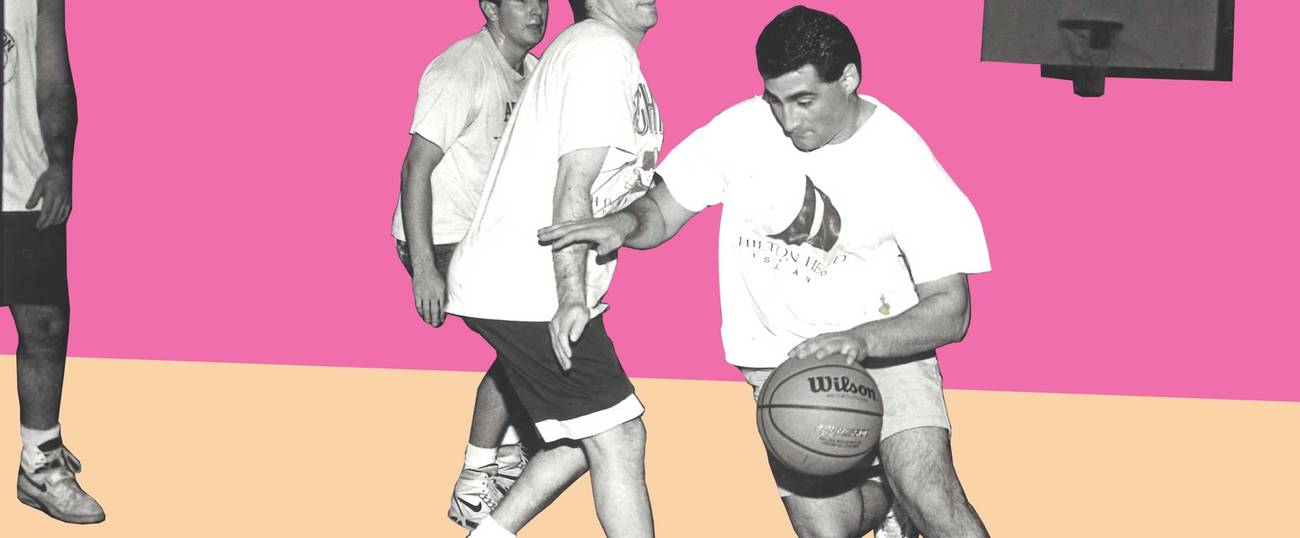

Jewish community centers had been around since the interwar years, a cross between a settlement house, an urban institution that had once attended to the varied needs of the community’s immigrant population, and a Y. Much like the synagogue-center, with which it was often confused, the Jewish community center served as a cultural clearinghouse where the Jews of the neighborhood could go for a swim, play basketball, attend a lecture, take a drawing class. Unlike the synagogue-center, though, it deliberately maintained an open door policy, a nondenominational perspective, or what one of its supporters called a “non-doctrinaire commitment to the universals in the Jewish heritage.”

By following its constituents to the suburbs, the JCC received a new lease on life. To be sure, synagogues, especially Conservative ones, flourished in postwar America, whose collective focus on both religiosity and the family made ample room for them on Main Street, or wherever zoning regulations prevailed. But the Jewish community center offered something else: a “new kind of Jewish neighborhood,” in Barry Chazan’s striking formulation, where Jews of all ages and allegiances freely associated with one another. A neutral third space, neither a house of worship nor a private home, but a “comfortable setting for Jews to be together,” it grew like a newly seeded lawn, becoming a hallmark of the suburban Jewish experience.

And today? In a curious twist of fate, JCCs that have either recently returned to the city or newly established themselves on the urban street, where they’re increasingly known, affectionately, as “the J,” are more than holding their own. This new designation not only aligns with the casual vibe of its constituents, but also signals the institution’s accessibility and contemporaneity. Meanwhile, those JCCs that remain in suburbia have fared less well and, in many instances, struggle financially and culturally. (Yes, there are exceptions; yes, I’m generalizing. Even so …)

In trying to account for the Y, the J, and the JCC—this alphabet soup of Jewish cultural institutions—I suppose one might point to the fickleness of the Jews or to changing charitable practices, or generational preferences—oh, those millennials!—or to Google, which takes the rap for lots of things these days. But I suspect there’s something larger, and more persistent, at work: the elusive relationship between Judaism and Jewishness, between religion and sensibility.

Years ago, in 1917, Kaplan wrote in his journal that “before we can have Judaism, we must have Jewishness,” intimating that the two went hand in hand. Sounds right. But how? Where and when does Jewishness leave off and Judaism begin? What’s the right balance between the two?

A century later, we’re still trying to figure this out.

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.