A New History of Holy Fire

A rabbinic classic, hidden in the Warsaw Ghetto, is given new life

It has long been a custom among Jews that religious literary figures are known by the titles of their books. For example, Rabbi Isaac Horowitz (1555-1630) of Prague, who later immigrated to the Land of Israel (Jerusalem, Tzfat, and then Tiberias), is more commonly known as the Shelah ha-Kodesh, after his work Shnei Luhot ha-Brit (Two Tablets of the Covenant), an intricate mixture of Kabbalah, Musar, and homiletics. Another case might be Rabbi Joseph Jacob of Pollnoye, one of the first Hasidic masters, whose is more commonly known as the Toldot, after his Hasidic classic Toldot Yaakov Yosef, the first Hasidic book to be published, in 1780. More recently, the Kabbalist Rabbi Yehuda Ashlag (1885-1954) is known as the Ba’al ha-Sulam, after his popular commentary to the Zohar.

What is somewhat odd about identifying such figures through their most recognized published works is that, in many cases, the masters in question never even wrote the books. Often, the published works appeared after their death (not unusual) and were also collected, edited, and redacted by others, from oral discourses or notes of the author. As the scholar Zeev Gries has shown, this kind of fuzzy, collective authorship is especially common with Hasidic literature, with its tradition of courts and disciples.

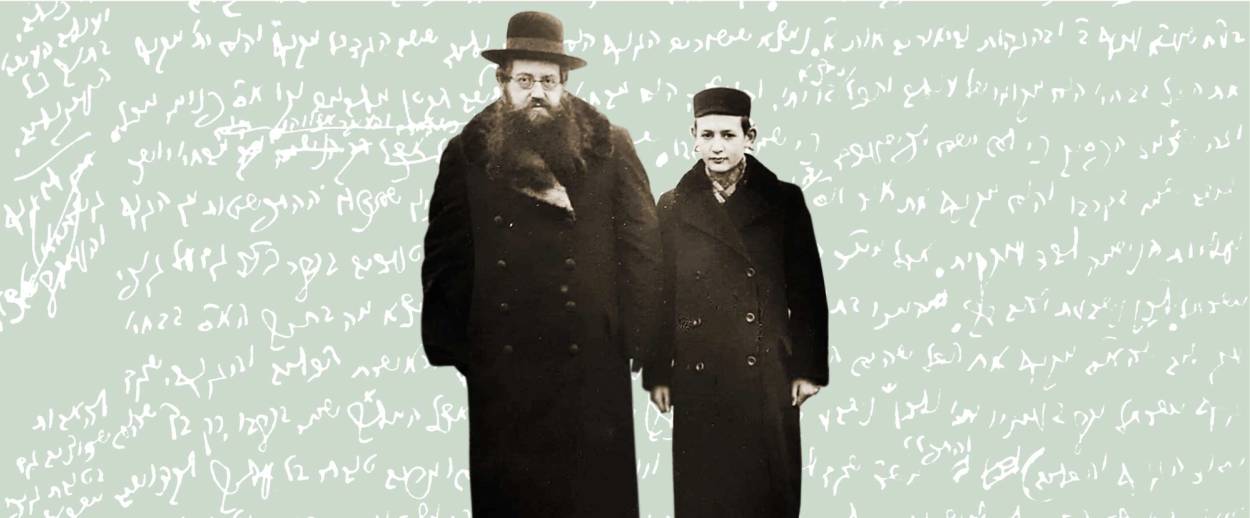

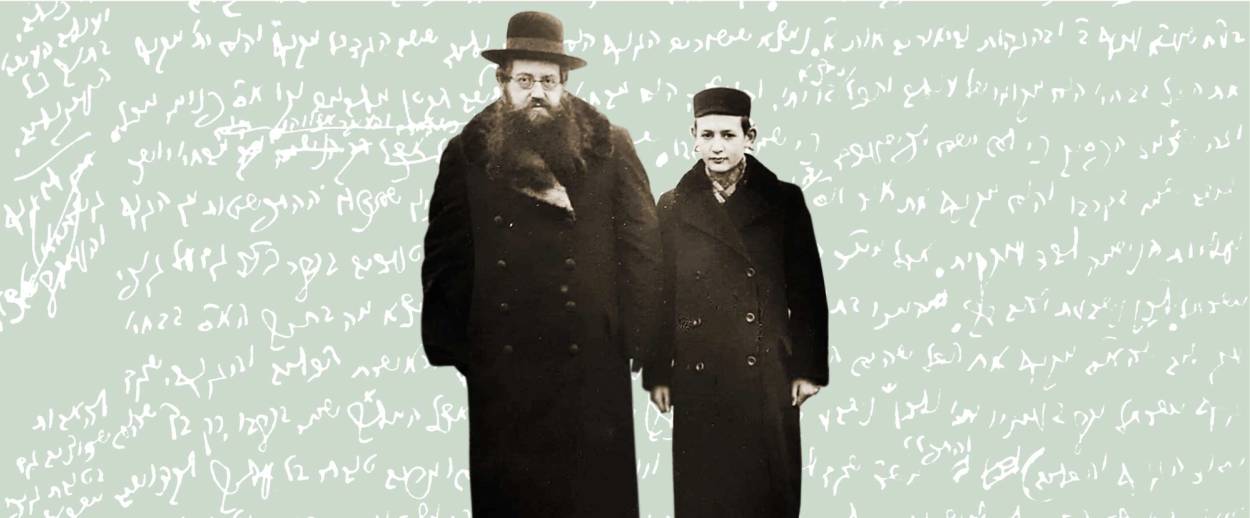

While there are certainly cases of Hasidic texts written by their author, there is one case that is especially significant. Rabbi Kalonymus Kalman Shapira (1889-1943), also known by the name of his signature work Esh Kodesh (Holy Fire), was a Hasidic rabbi in the Warsaw ghetto who tragically perished in the Holocaust in 1943. Esh Kodesh (a name that, as we will see, came later) was a collection of sermons Shapira delivered during his years in the ghetto. An earlier collection of sermons was published under the title Derekh Ha-Melekh. The ghetto sermons have a fascinating history apart from the author, mostly about how they were hidden and later found after the war, then published in Israel in 1960. Israeli scholar Daniel Reiser has recently published a monumental two-volume work in Hebrew, Derashot m’Shanot ha-Za’am (Sermons From the Years of Fury), that will change how this important work will be read in the future.

Unlike many other Hasidic works, these sermons are dated, so we can actually trace his Torah discourses with the events in the ghetto, even though, as Reiser and others note, Shapira never mentions the Nazis; indeed, he rarely mentions any particular event, including the deaths of his children. Whether this was also the case in his oral presentations, we cannot know for sure. In any event, the dating (unusual but not unprecedented in Hasidic literature) offers us an almost unique window into the way a Hasidic master used the Torah as a lens or filter to respond to a world collapsing around him. Esh Kodesh thus serves as a kind of spiritual diary of a public figure, torn between his personal anguish and his communal responsibility to continue to instill hope to his congregants in a quickly darkening world.

I have written about Shapira in these pages before, but here I want to focus not on the man, but on his book, and more specifically to recognize Reiser’s significant contribution to its history.

The story of how these sermons made their way to the Oyneg Shabbos archive of Emanuel Ringelblum in the Warsaw Ghetto, where they were hidden with tens of thousands of other documents, is complex. Samuel Kassow’s Who Will Write Our History?: Rediscovering a Hidden Archive in the Warsaw Ghetto (2009) meticulously tells the story of how Ringelblum and his coterie collected massive amounts of ghetto materials, hiding them in metal milk canisters that were buried and discovered after the war. Kassow suggests that Ringelblum heard of Shapira from Rabbi Shimon Huberband, who worked with him. Huberband was an Orthodox Jew and historian, and also a relative of Shapira. Given the mythic status of Shapira in light of his posthumous published work—he was often touted as “the Rebbe of the Warsaw ghetto”—it is interesting that Ringelblum, a learned albeit secular Jew, had simply never heard of him.

The documents Shapira apparently gave to Huberband were not only the papers that would later make up Esh Kodesh, but three other complete works, each with a separate title. All of these works were also published after the war. These other works all seemed to be either copied by a scribe or, in one case, typed; none was in Shapira’s handwriting. Each had nominal marginal notes and corrections in Shapira’s hand. The ghetto sermons, however, seemed to all be in the author’s handwriting and had no official title except “Words that I said on Shabbat and Yom Tov from the years 1940, 1941, and 1942.” In a separate note Shapira added to his papers, the sermons were referred to in three different ways, simply Torah Novella (Hiddushei Torah), in Yiddish Hiddushei Torah auf Sidras fun de-yohren 1940, 1941, and 1942, and in Hebrew Hiddushei Torah m’Shanot Ha-Za’am (Torah Novella From the Years of Fury). Reiser uses Shapira’s Hebrew title for his own edition. We really don’t know why Shapira used three different ways to describe these writings, but for Reiser, and for us, the crucial element is that these sermons were not only written in Shapira’s own handwriting but also included his own copious marginal notes, additions, corrections, and emendations

As was customary among many Jewish thinkers who spoke on Shabbat and Yom Tov, Shapira would deliver his sermons on Shabbat in Yiddish, then Saturday night would record them in rabbinic Hebrew. The use of rabbinic Hebrew as opposed to Yiddish was likely due to the author’s wish for a readership beyond those who read Yiddish; plus, of course, that Lashon ha-Kodesh (rabbinic Hebrew) was the language of Torah. While Shapira was certainly addressing his constituents in these sermons, Reiser notes that the effort to record them afterward, especially under such dire conditions, implied that Shapira was looking beyond the ghetto. As Reiser puts it, “The Admor [an honorific “Our master and teacher”] saw these sermons as having relevance beyond their time.” This may also be why Shapira refrained from recording specific events they may have been responding to. Shapira was voicing his own inner desperation, trying to inspire his flock, and also writing for posterity at a time of utter confusion and uncertainty.

After their postwar discovery, a photocopy (microfilm) of the manuscript made its way to Israel, where a team was assembled to transcribe Shapira’s very difficult handwriting into a printed text. Reiser provides many examples of Shapira’s terse handwriting and the ways in which it was mistakenly rendered by the editors. The text was published in 1960 under the name Esh Kodesh. This was the only printed edition until Reiser’s volume appeared in 2017. The name Esh Kodesh was decided upon by the editors and publishers. In the Introduction to the 1960 edition we read, “We have called this book Esh Kodesh as a remembrance to all the holy ones who perished in fire … and the name also hints to our master, his father, and his son [who also perished in the Holocaust].” That is, our master died in a holy fire and the names of his father and son were Elimelekh Shapira, or Esh.

The original manuscript exists in the Jewish Historical Institute (ZIH) in Warsaw, and there is a copy in the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. Many excellent works have been written about Esh Kodesh by prominent and younger scholars (a volume will soon appear from a 2017 conference on Esh Kodesh in Warsaw) but, trusting the work of the first printers, none of them to my knowledge referred back to the original manuscript. Much of the work on Esh Kodesh has taken a developmental approach, that is, tracking Shapira’s thoughts as time passed in the ghetto, as things became darker and more hopeless, until the Great Deportation (Aktion) in July 1942. The last full sermon included in Esh Kodesh was delivered in summer 1942 on Shabbat Hazon, the Shabbat before Tisha B’Av, immediately preceding the Great Deportation. Studies depict a man of faith stretched beyond his limits; by the middle of 1942, most of his community had perished, including his family, and he was increasingly alone with his thoughts, struggling to make sense of the tragedy that was unfolding before his eyes. Scholars differ as to how he fared: Did he remain a believer as before? Did his faith waver, change, or get destroyed? We will never know the answer.

*

Reiser decided to return to the original manuscript and compare it to the printed edition. As one can imagine, he found numerous errata, many not very significant. But he also found something quite important. The manuscript was replete with marginal notes, crossing out and rewriting sentences, sometimes entire paragraphs, and in a few cases, footnotes that altered and revised the meaning of the original text. Through meticulous work, and with the use of cutting-edge technology, Reiser determined that these markings, notes, and glosses were not part of the initial transcription of the sermon but rather the product of Shapira continuing to return to his earlier drafts and make corrections and additions over the course of three years. Thus, the text is not the product of a linear stream moving through time, but a jagged series of revisions and emendations from 1940 through 1942. The developmental approach, tracing Shapira’s increasing anguish and difficulty making sense of the world around him, is made more complicated when we realize that the text is more layered than we thought. Reiser writes:

It seems to me that we cannot limit each independent segment as paradigmatic. We can locate notions of suffering that come later in the text already in earlier sermons and earlier notions of suffering in later sermons. I do not mean to fully repudiate the developmental thesis of the Admor’s view of suffering but rather give it more nuance. In general, it’s very difficult to discern a clear developmental theory of such sermonic writing, all the more so when the sermons were written under such duress, at a time of anguish and pain, when the author (darshan) is so upset and depressed. It is hard to believe that the Admor was able to develop this in an ordered manner and even less likely in a subconscious manner. For example, in the beginning of 1940 in a sermon on “The Life of Sarah” (Genesis 23) he already exhibited a later position on suffering that does not come from sin or distance from God.

What Reiser means here is as follows: The developmental theory surmises that as time wore on, Shapira became less and less sure of normative covenantal theology, holding that we are punished for our sins, that what Jews were experiencing in the ghetto was no different than what others Jews had experienced throughout history. Many studies have exhibited in his developing theory of suffering a progressive sense of despair, combined with his belief that the events in the ghetto did not constitute a unique time that fractured the divine covenant with the Jews. In one sermon in early 1942, Shapira writes:

“… [F]aith must be with one’s whole being (be-mesirat nefesh—self-sacrifice) because all mesirat nefesh comes from faith. If faith is not exercised with mesirat nefesh how can mesirat nefesh exist at all! The notion of mesirat nefesh in faith must be operative and even when God is concealed (ha-hester) one must believe that everything is from God and is for the good and the just and all suffering is filed with God’s love for Israel … In truth there is no room for questioning [heaven forbid]. Truthfully, the sufferings we are experiencing are like those we’ve suffered every few hundred years … What excuse does one have to question God and have his faith damaged by this suffering more than the Jews who suffered in the past? [my italics]

The developmental theory suggests that at some point soon after, his belief that the ghetto was parallel to previous events in Jewish history became inoperative. In a 2010 essay on Esh Kodesh, James Diamond succinctly suggests that, after the summer of 1942, “the traditional rationale for suffering as a necessary stage in the unfolding of the divine plan [was] … no longer viable.” What becomes of Shapira’s faith remains a matter of dispute. What Reiser suggests, however, is that we can find specters of that later despair even in earlier sermons. This is because Shapira kept returning to his earlier sermons and edited them as time went on. What we have, then, is not a linear but a layered text, and oftentimes those emendations which exhibit Shapira’s own rewriting of earlier sermons do not make their way into the printed text, which reads in a much more linear fashion.

Reiser presents this to his reader in a brilliant manner. In volume one he provides us with a new text, one that incorporates the notes, additions, and emendations, a clean Esh Kodesh that is different from the 1960 edition. In volume two, he offers his reader a window into the toils of his labor. On the right side of the page, he reproduces a facsimile of the handwritten manuscript. On the left side he reproduces the 1960 edition of the text with all of Shapira’s handwritten additions, emendations, notes, etc., in four colors, indicating four levels of the author’s edits, so the reader can see the changes Shapira made in reviewing and editing his own text. As far as I know, this is the first time that someone has edited a Hasidic text in this wonderfully helpful manner. In particular, this exercise not only corrects printing errors but invites the reader to enter into the word of a Hasidic master who, during unimaginable horror, not only recorded his sermons but continually returned to them to correct, change, and emend them in light of the dire circumstances he faced. As time went on, he continually seemed to question earlier locutions and returned to earlier sermons, not so much to change them but to insert hints of later revelations about his circumstances. The developmental approach may still hold, but not as before. Shapira’s own editorial hand must now be taken into account. He is less a victim than ever, more an agent. Esh Kodesh was not only a book Shapira wrote, but a book, Reiser shows us, that he continually read, perhaps not only to correct but also to inspire him in those dark days of despair. Shapira was both Esh Kodesh’s creator and its most ardent reader.

As for Reiser, his 2018 Yad Vashem Book Award for this work was very much deserved. This is, he shows us, not only a Hasidic book; it is a testament to the struggle of faith against insurmountable odds. Few before Reiser have been able to offer us such an intricate and intimate gaze into the world of a brilliant mind and a caring heart whose life was cut short by the evils of human depravity.

*

In Israel I knew a boy. His parents named him Esh-Kodesh. How many children are named after a book? And what a book! Esh-Kodesh Gilmore was a sweet boy and grew to be a wonderful young man. He was the eldest of six children. I remember him and his friends playing soccer in the long summer afternoons on Moshav Modi’im. At the age of 25, married with a young daughter, he was working as a security guard for bitucah leumi, the institute for national insurance. On Oct. 30, 2000, while working, he was murdered by a terrorist’s bullet. One bullet. Like Shapira he was the victim of baseless hatred. May Esh-Kodesh Gilmore and his namesake find peace in God’s embrace. This essay is dedicated to his memory.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Shaul Magid, a Tablet contributing editor, is the Distinguished Fellow of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College and Kogod Senior Research Fellow at The Shalom Hartman Institute of North America. His latest books are Piety and Rebellion: Essays in Hasidism and The Bible, the Talmud, and the New Testament: Elijah Zvi Soloveitchik’s Commentary to the Gospels.