The Hummus Bible

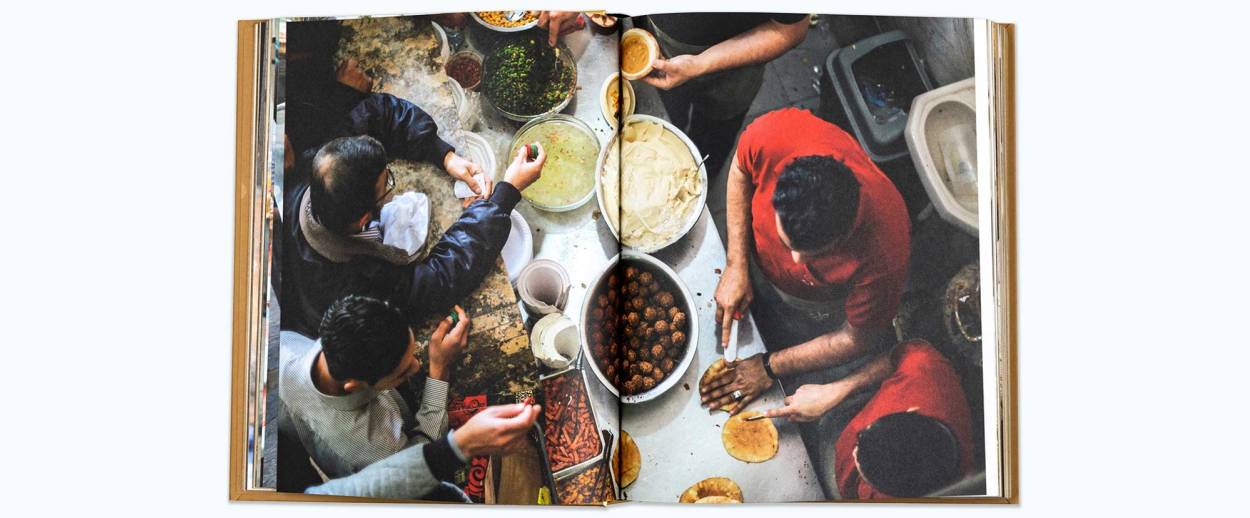

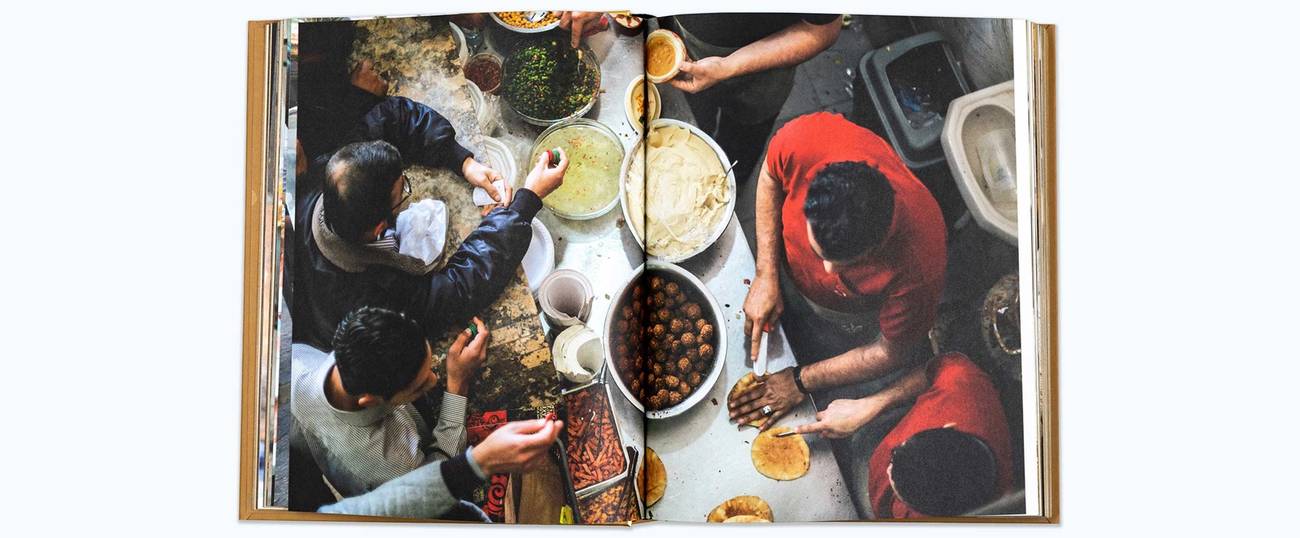

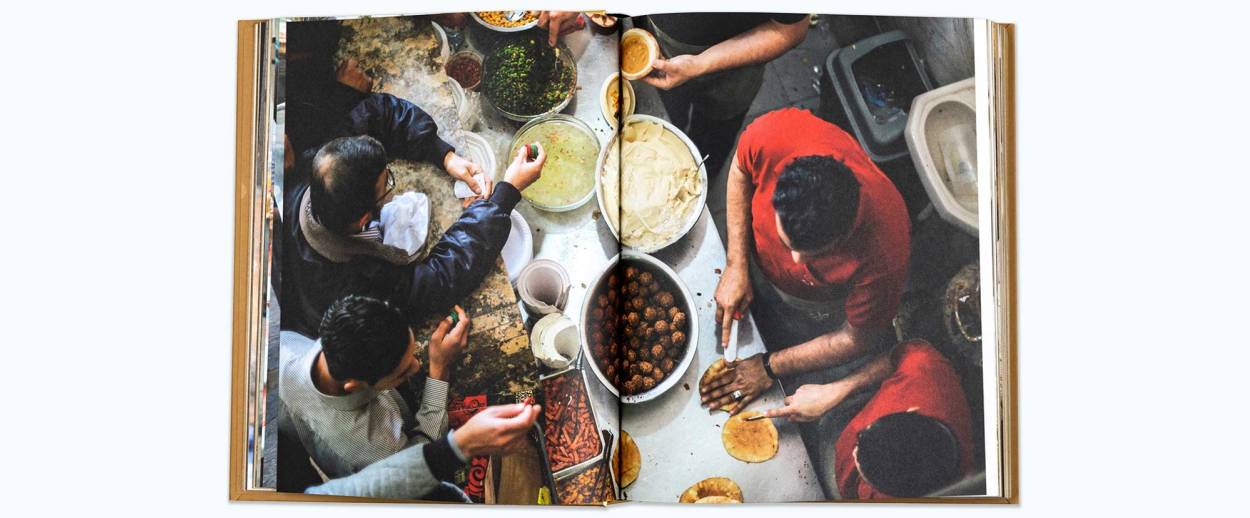

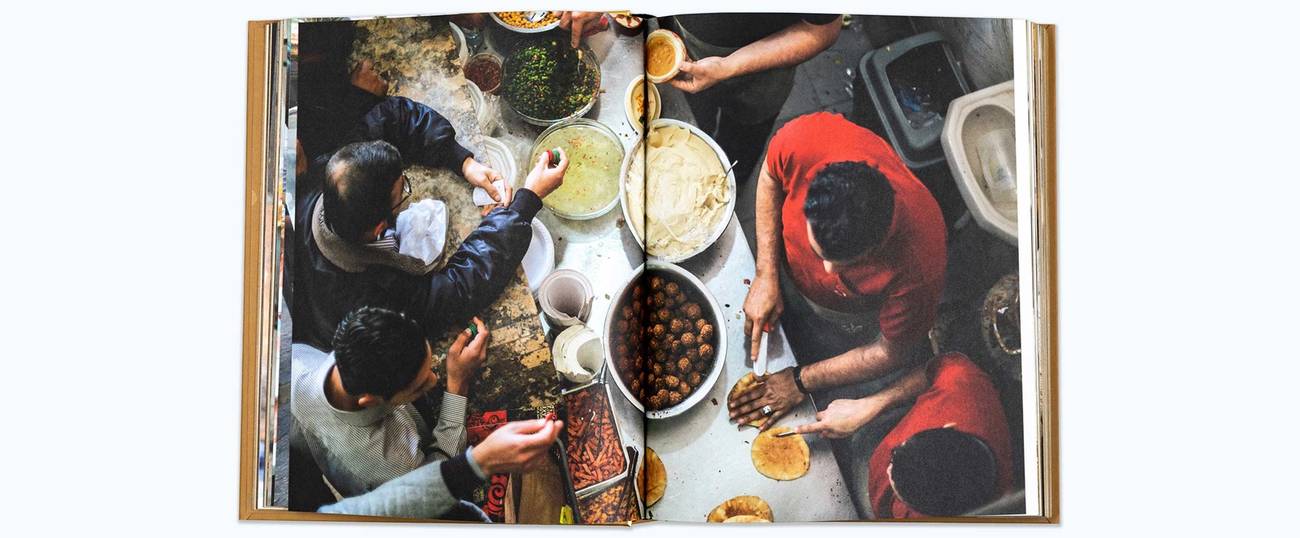

A new coffee table book takes readers on the trail of the magical chickpea, across the Middle East

A beautiful new coffee table book is dedicated to the holiest of Israel’s street foods.

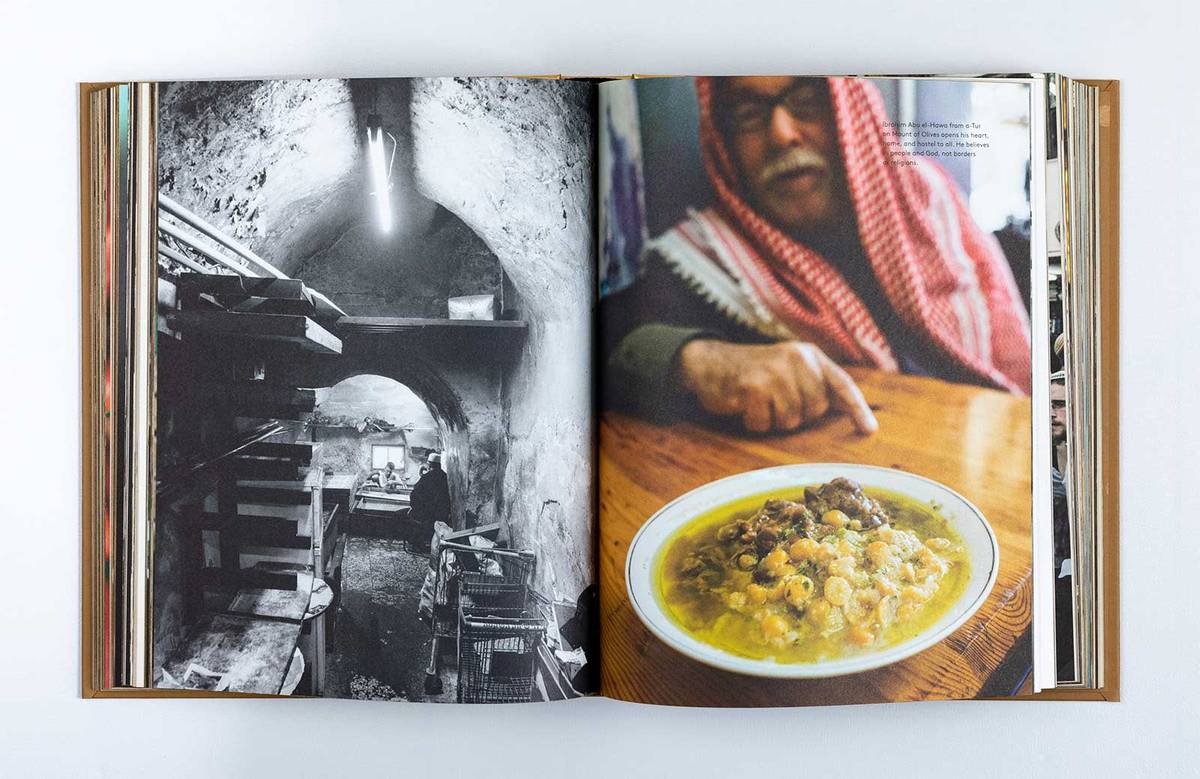

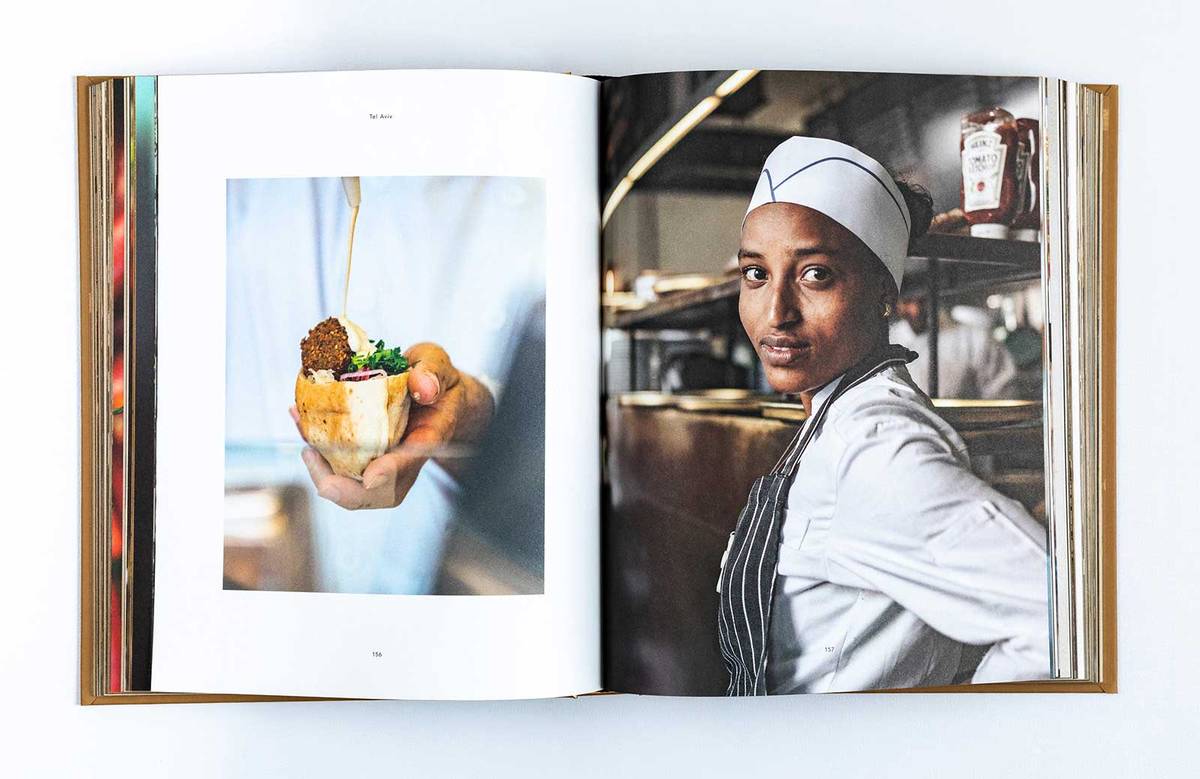

On the Hummus Route was created by prominent figures in the world of culture, cuisine, and science, in a first-of-its-kind collaboration led out of Paris across nine Middle Eastern cities, from Cairo all the way to Damascus, via Gaza, Jaffa, Tel Aviv, Nazareth, Jerusalem, Akko, and Beirut.

Hummus—in Hebrew and Arabic—is the word for both the dish and the chickpeas that it is made of. On the Hummus Route discusses both—in English—from different angles, returning from each location with information, photos, illustrations, and other artwork, recipes for various local delicacies made out of/with chickpeas, historical facts, legends, and anecdotes. It also includes texts by various experts, from Karim Haidar—head chef and co-owner of Askini restaurant in Paris, and the founder of the Academy of Arab Cuisine—to world-leading researcher of Jewish cuisine and renowned cultural anthropologist Claudia Roden, originally from Cairo. In short, this is a hummus bible, its golden-brown cover the color of hummus itself.

Behind the book are three people: Ariel Rosenthal, the initiator, is the chef and owner of the acclaimed restaurant Hakosem (meaning “the magician”), a major culinary landmark in Tel Aviv serving a menu primarily based on chickpeas. Orly Peli-Bronshtein is a culinary expert and chef, boasting a long line of cookbooks in Hebrew, and the chief gastronomic editor of Israel’s leading culinary magazine Al HaShulchan. The chief editor and designer of the book is Dan Alexander, the founder and creative director of Dan Alexander & Co., an international strategic branding firm based in Paris, winner of the prestigious Gourmand International Cookbook Award.

“I started a journey 18 years ago when I opened Hakosem,” Rosenthal told me when I met him and Peli-Bronshtein at his restaurant. “I slowly realized that there is something very special in this raw material. In the last 10 years the world is starting to get to know hummus and falafel better. It is absurd that we Israelis have to bring these Arab foods to the world, but in fact that is what is happening. People like Eyal Shani and me and other Israeli chefs are bringing chickpeas to the global stage. This book, for instance, is full of recipes from the Arab world.”

“Some of us Israelis are Arabs, too,” added Peli-Bronshtein. “Hummus isn’t a Muslim thing, it’s an Arab thing, and there are many Jewish Arabs.”

In a personal essay in the book, Rosenthal writes: “If I was asked to describe the chickpea in one word only, that word would be wonder. A wonder in taste, versatility, and a wonder endorsed by doctors, nutritionists, and naturopaths for its many health benefits. The chickpea is a high-quality, protein-rich legume full of antioxidants, folic acid, vitamins, and minerals such as calcium, iron, magnesium, potassium, and more.”

As the book shows in its many recipes, chickpeas can be used not only for making hummus and falafel, but to make many different savory, sweet, or spicy foods and they can be used cooked, roasted, dried; there is even chickpea flour. The most surprising thing that can be made out of chickpeas is probably vegan meringue—although it isn’t even made out of the chickpeas themselves but out of aquafaba, the water you cook them in.

But still, the dish most closely associated with chickpeas is hummus. Americans often mistake hummus for a dip, which in Israel would be considered blasphemy. In Israel, hummus is a dish in itself, served as breakfast or lunch. You can eat it using a piece of pita (in Hebrew the verb for doing so is lenagev, meaning “to wipe”) but you can also use a fork, especially if your hummus has cooked chickpeas or ful (fava beans) on top and a hard-boiled egg on the side. Supermarket hummus is considered a spread, which you can put in your kid’s sandwich for school. Even though supermarket hummus is industrial, the companies that manufacture it try to market it as no less soulful than hummus that you get in a hummusia (Hebrew for a hummus eatery). One of the most quoted commercials in the history of Israeli TV belongs to hummus manufacturers Tsabar: “Hummus is made with love, or not made at all.”

*

The origins of hummus and falafel aren’t known for certain, but there are assumptions. “Hummus probably was born in Damascus,” Peli-Bronshtein told me. “I think it was born by accident and chances are that the msabbaha—cooked chickpeas with tahini—was born first. Msabbaha and hummus are very similar except for the texture; in msabbaha the chickpeas remain whole. The origin of falafel is also uncertain. The popular theory is that the dish was invented in Egypt by Coptic Christians, who ate it instead of meat during Lent.”

Peli-Bronshtein and Rosenthal maintain that both hummus and falafel changed a lot when they came to Israel. “First of all, Israel industrialized hummus,” Peli-Bronshtein explained. “Israelis also added a hard-boiled egg next to the hummus. And the large quantities of tahini that are part of the hummus these days also are an Israeli thing. Not only Israeli, but it’s definitely not as people used to make hummus in the old days. When the fellahs used to eat their hummus in the morning it hardly contained any tahini at all. It wasn’t a paste, it was much more grainy. You would add one teaspoon of tahini and quickly close the jar before the fumes escape. When tahini became less expensive people started adding more of it to the hummus because it makes it more luxurious. A long time ago in Israel when you went to eat hummus, hummus was all you got. You didn’t even have forks or drinks or even cups. Everybody would drink water from the same clay pitcher. You can still find places like that in Eastern Jerusalem. In time, people started understanding the potential of hummus and hummus places started changing. They started offering drinks and salad and putting music on. Families started coming. They made eating hummus fun, like going to any restaurant.”

Rosenthal sees himself as a perfect example of the process that hummus went through in Israel. “Israelis are very much influenced by other cultures,” he said. “Personally, I travel a lot around the world: I love French food and I’m also crazy about American junk food. When I make hummus, naturally I make it the way I like it, which means I make it with a lot of tahini because tahini is fat. We don’t use butter like in Paris or bacon like in the U.S., so I put a lot of tahini in my hummus and pour a lot of olive oil on top. At Hakosem the hummus is made with 50% chickpeas, 50% tahini. The pita also changed in Israel. In Arab hummus places the pita isn’t important. I think that the quality of the pita is an important part of the hummus or falafel experience. I put great emphasis and pride in the pitot that I use.”

Falafel also changed a lot. The original Egyptian falafel is called ta’amiya and was made out of fava beans. “There is one theory that Napoleon’s soldiers knew the ta’amiya,” Peli-Bronshtein said. “When they came to Israel they didn’t have any fava beans but they found chickpeas and thus the chickpea falafel was born. Of course, we don’t know if that’s true.”

Peli-Bronshtein and Rosenthal’s love for the chickpea is a sentiment shared by many Israelis. “We believe that there’s much more to hummus than the fact that it’s healthy and tasty and cheap,” Rosenthal told me. “I firmly believe that there is something spiritual in chickpeas. I keep hearing from people, from all over the world, that hummus or falafel brought them close to tears. That’s not something you say about oxtail ravioli, even though I love pasta. There is something powerful about chickpeas that makes these dishes emotionally moving.”

Peli-Bronshtein added: “If you water your plants with the water you soaked your chickpeas in, they grow better. Also, the soil in which the chickpeas grow improves. There are farmers who plant chickpeas between their crops only in order to improve the soil. Chickpeas can also help end world hunger. Nowadays volunteers grow chickpeas in areas of famine in Africa because you don’t need refrigeration or special storage spaces to keep them—you can just keep them dry.”

These facts, and others in the book, might surprise some American readers, but the spiritual value of hummus will come as no surprise to Israelis. It’s no wonder that the first thing many Israelis do when they return home from abroad is go eat hummus.

“Hummus is a magical dish,” concluded Yaniv Gur Arie, owner of the Nachlaot company, which does research and development of culinary products for the food industry. For the last seven years Gur Arie has been the research and development chef of Strauss’ dips-and-spreads brand, Achla—Israel’s leading supermarket hummus manufacturer. “On one hand it’s a very nutritious dish with very healthy ingredients that gives you high quality full protein, no less than meat, and on the other hand it’s very tasty and it also contains tradition and culture. If you add to this the fact that it is cheap and the rising trends of veganism and Mediterranean cuisine, it is clear that the world has discovered a new basic food. These are revelations that happen once a generation, like bread, hamburgers, pizza, or sushi. Now it’s the turn of hummus.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Dana Kessler has written for Maariv, Haaretz, Yediot Aharonot, and other Israeli publications. She is based in Tel Aviv.