Hot Wheels

Roller derby has a rich Jewish (and feminist) history

My 14-year-old daughter, Maxine, is a derby skater. She’s been skating with Gotham Girls Junior Derby for three years now, under the derby name Maxiemum Damage. The number on her jersey is 9.7, “because that’s the size of an earthquake on the Richter scale that means total annihilation,” she said in an interview with Tablet, aka her mother.

We love derby. It provides a hugely nurturing, supportive, sweet, and feminist environment for young athletes. No, it is not terrifying. The first thing a kid learns is how to fall safely. (Curl your body into a little ball like a pill bug, pulling in your arms and legs and taking care to protect your head.) Coaches are vigilant about not letting kids even walk on the track unless they’re in full protective gear. New skaters move up through various levels, passing assessment tests of their skills, until they reach level 3, which is the full-contact, hip-checking, collision-filled sport played according to Women’s Flat Track Derby Association rules.

At Maxie’s first practice, back when she was about as steady on her skates as a newborn colt, the session concluded with a short lesson from the two coaches (both skaters in Gotham Girls Roller Derby, GGJD’s parent league) about a Great Woman Athlete in History. One coach explained who Babe Didrikson Zaharias was while the other made enthusiastic listening noises. I kvelled at the excellent pedagogy.

Junior derby embraces different body types, skill levels, neurodiversity, gender expressions, and sexual identities. As Maxie told Tablet, aka, again, her mother, “This has been the healthiest, friendliest, and most accepting environment I’ve ever been a part of.” For kids who get bullied for being different, GGJD is a respite.

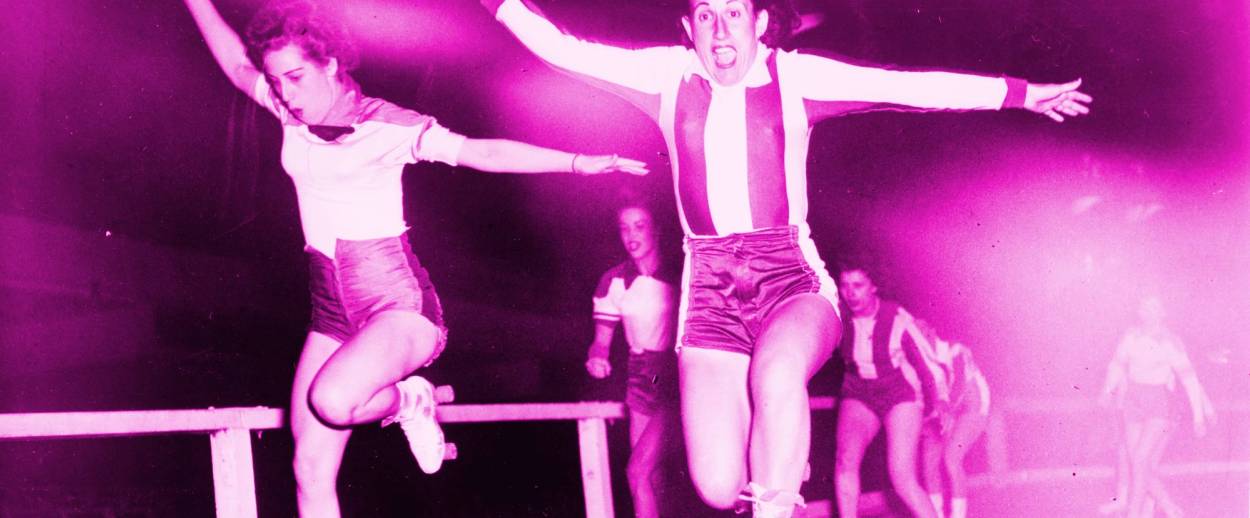

But many people’s impressions of derby are based on creaky vintage or cartoonish depictions of the sport. When I tell people that Maxie is a derby skater, they imagine sex kittens on wheels theatrically flipping over railings or vicious bench-clearing fistfights. Nope. But it’s worth looking back on yesterday’s derby, with its rich Jewish history, to see how we got from point A to point B.

*

Roller Derby (both letters capitalized, if you please) sprang fully formed from the mind of Leo Seltzer, an event promoter in Chicago, on Aug. 13, 1935. Seltzer was the son of Romanian immigrants who fled forced conscription for their two older sons at the turn of the century. Seltzer’s father was a master wood craftsman and was promised a job by a carriage maker in Chicago. Immigrant craftsmen were frequently underpaid, so Seltzer’s father soon decided to go west; he wound up working as a furrier and rancher in Montana.

As a young man, Seltzer went into promotion for the newborn motion picture industry and for sporting events. But when the Great Depression hit, he needed to come up with more affordable entertainment ideas. He’d promoted walkathons, and when he read a statistic that over 90% of Americans had roller-skated—men and women alike—a plan came together. Sitting in a Chicago restaurant, he began scribbling ideas on a tablecloth.

Seltzer copyrighted the name Roller Derby on July 14, 1935, and a month later, 20,000 spectators filled the Chicago Coliseum. At first, the sport was an endurance contest, like a dance marathon, with teams made up of both men and women skating 57,000 laps—around 4,000 miles—on a banked track, all to the accompaniment of a jazz orchestra led by big-time bandleader Erskine Tate. There were bright lights and an illuminated map of the United States. Every night the skaters raced to a “destination.” “You know, from Chicago to Detroit and Detroit to Cleveland and Cleveland to Pittsburgh and so on,” Seltzer told sportswriter Frank Deford. The fastest teams won prizes. “I see now that using women was the big thing,” Seltzer told Deford. “What we’ve got going now is a game whose success, in part, is built on the cynicism of the men because they can’t believe it’s a real sport … but the women, thank God, bring them along and at the games these men go wild.”

A 1936 British newsreel breathlessly described “the great Roller Darby”—“Fahstah! Fahstah! Fahstah! Wouldn’t it be dreadful if one of them fell down!”

But the sport didn’t really take off until 1938, when sportswriter Damon Runyon told Seltzer that the accidental falls and collisions were the best part. Seltzer consciously pumped up the aggression, and people loved watching the women, especially, go at it. “It’s time for the little ladies to start their merry round of riotous roller rough stuff that the fans go for!” an announcer exclaimed on a newsreel. “They say the men skate faster, but when it comes to rough stuff, just ask the fair sex who’s in there pinching every time. Why, the ladies, bless ‘em!”

Seltzer’s brother Oscar manufactured “the official Roller Derby skate,” which had maple wood wheels. They were fast but required a dusting of plaster of Paris on the track to be even faster. “The wheels churned the pumice into the air and out into the crowd,” Deford noted. “Skaters and fans both left the arena appearing as if a dandruff epidemic was on the rampage.”

Seltzer took the show on the road, under the watchful eye of tour manager Sid Cohen. As Deford put it, in classic hard-boiled sportswriter-ese, “It is still like a breath of the Depression, a carnival air of the dance marathons that spawned it. It is still one-night stands and advance men, Laundromats and greasy spoons, and children who collect in excited clamor to press close to these wonderful skaters who have come so far to perform in their very own town.”

Early on, Seltzer clued in to the potential of television. In the late 1940s, TV execs were desperate for programming—they sometimes went off the air because they had nothing to run. So Leo convinced CBS to buy broadcast rights to Roller Derby’s 13-week stint at NYC’s 69th Regiment Armory on the Upper East Side. Tickets were $1.65, but once the matches were televised, demand surged. Seltzer raised the price to $3.30. Before long Roller Derby was at Madison Square Garden; tens of thousands of people attended matches fought by teams like the New York Chiefs, the Brooklyn Red Devils, and the Jersey Jolters.

When CBS’ broadcast rights expired in 1949, Seltzer sold the rights to ABC, which ran three matches a week. Execs kept demanding more. Overexposure became a problem. Sponsorship opportunities didn’t pan out. Derby was in trouble.

*

In 1957, Leo Seltzer wanted out. His son Jerry, who passed away just last month, took over and shepherded the sport through the 1970s. He, too, understood the power of the broadcast medium. When videotape, with its clearer images than old-fashioned kinescopes, debuted, Jerry took advantage. He used telecasts to drum up interest in local markets, then brought the skaters in to do matches and personal appearances. As more UHF stations cropped up, they craved programming (sense a theme here?) and began buying local rights to show Jerry’s Derby tapes. By 1970, games were taking place at Kezar Pavilion in San Francisco and videotapes were being sent to 125 stations around the country. Fights on the track were over-the-top and fun to watch. Few people know that Roller Derby regularly got higher ratings than baseball or golf, and achieved nearly the same ratings as basketball and football. “Every week at least three million persons in the United States see a Derby game on television,” Deford reported in his 1971 classic Five Strides on the Banked Track (long out of print, newly available in e-book form). “Slightly more than half of these people are women, a statistic no other sport can claim.”

Yet male execs and the male gaze still held sway. Deford noted sadly that the women’s femininity was “most maligned, but only a few are Lesbians.” (That capital L is his.) In 1970, Jerry formed a production company and made a purportedly documentary movie, Derby, that focused on an up-and-coming male skater. It depicted women—skaters, wives and fans—primarily as competition for his dudely attention. The 1972 movie Kansas City Bomber starred Raquel Welch as a sexy skater, brawling with other women, sleeping with the male head of the league, and screaming at a rival on the track, “You’re a big fat tub of lard and you can’t skate any better than you look!” This behavior would not fly in today’s derby.

Buddy Atkinson, who ran the Roller Derby training school in 1971, was married to a skater and had a skating daughter-in-law. Nevertheless, he told Deford, “The best thing would be to take all the girl skaters, put ‘em in a little sack and drop ‘em in a river.” Deford wrote, “Certainly, there is no doubt that it is the women who give the game its tawdry, sideshow image. But there is also no doubt that it is the girls who bring people into the arenas—even if the fans stay to enjoy the faster, harder men’s play more.”

Men perpetually seemed anxious about the passionate fandom of women spectators. Observing a yelling female patron, Jerry Seltzer told Deford, “Sometimes I think we must be doing a service. I think we must be keeping that woman from going home and killing her husband tonight. And every night, there is some woman like that.” A persistent legend held that a furious fan once threw her baby at derby star Midge “Toughie” Brasuhn. “Luckily, Toughie caught the baby,” Deford wrote. “And it was so young it was wrinkled,” female star Joanie Weston informed Deford somberly.

Eventually Jerry decided to move on. He shut down the derby in 1973. In 1974 he went on to found the computerized ticketing outfit Bay Area Seating Service, which was eventually acquired by Ticketmaster, where he became an executive. He served on the board of the American Red Cross in the Bay Area, rode with the Hells Angels, smoked pot on Willie Nelson’s tour bus, and managed a Soviet refusenik rock band.

Derby seemed poised to fade away.

*

In 2001, a handful of badass women in Austin decided to revive roller derby (no capital letters now), making it all-female and skater-operated. It would still be campy, but now women would be creating the narrative. They’d embrace the “unfeminine” athleticism of the sport. Instead of calling games “matches,” they’d be called “bouts,” adopting boxing terminology.

Texas derby was a hit. Its success led to the growth of other teams. Traditional banked-track derby (as created by the Seltzers and seen in the movie Whip It) was joined by flat-track derby, which is easier to set up and break down. Here in New York City, GGRD and GGJD skate on a flat track. They practice in a former warehouse in Williamsburg and compete, for the most part, on a portable track at John Jay College in Manhattan. GGJD’s coaches are adult GGRD skaters—Maxie invariably waffles about which adult team to root for when we go to GGRD bouts because she’s had coaches from all the teams (Manhattan Mayhem, Bronx Gridlock, Brooklyn Bombshells, and Queens of Pain) and hates to play favorites.

Now there are hundreds of flat-track and banked-track leagues around the world. France has 116 leagues, Argentina has 65, Japan has two. There’s a thriving team in Tel Aviv, and if someone wants to set up a match with the team in Lebanon, it would make an awesome movie, I’m only saying. The rules for flat-track and banked-track are slightly different, and both are different from derby in the Seltzers’ day, but here are the fundamentals: Jammers are fast skaters who score points by circling the track. Blockers are defensive players who try to protect their own team’s jammer and prevent the opposing jammer from scoring. Maxie, for instance, isn’t a superfast skater, but she has a great sense of strategy and she’s strong, so she’s a really good blocker. As Danielle Sporkin (the Jewish president of GGRD, who of course goes by the derby name Spork Chop), president of Gotham Girls Roller Derby (and a coworker of my husband’s) told The New York Times, “It’s one of the only sports where you’re playing offense and defense at the same time.” Seeing tattoo-covered athletes crashing into each other, doing fancy footwork and leaps and speeding past one another, is thrilling.

Kids today grow up surrounded by narrow depictions of femininity; derby can be eye-opening. There are male teams now, too, but way fewer than there are women’s teams. Men are welcome, however, to officiate at women’s games. Which means that just as little kids today are sometimes shocked to learn that men can be pediatricians and rabbis (because they’ve grown up not knowing that historically, pediatricians and rabbis were men), little GGJD fans are often shocked to learn that men can play roller derby, too.

On his blog, Jerry Seltzer fretted about the lack of collective memory about his family’s contributions to derby. But he also celebrated the achievements of today’s woman- and player-led leagues. He perpetually encouraged audiences to attend bouts, urged skaters to get health insurance, ran national derby blood drives, and shared his classically Jewish progressive politics (he called Donald Trump “the Orange Dolt,” spoke out against the entitled Stanford swimmer/rapist and the judge who went easy on him, worked for gun control, and urged donations to Planned Parenthood).

And the Jewish history of roller derby rolls on. There’s a new all-Jewish flat-track derby team composed of Jewish women skaters from around the world; they have helmet covers with the Lion of Judah on them and skaters use their Hebrew names as their derby names. This November at the international WFTDA championships, in Montreal, they’ll skate against Team Indigenous, a team composed of skaters from (duh) indigenous backgrounds. The match is being called We Are Nation: A Game Without Borders. (The bout will also be livestreamed on WFTDA.tv.) The idea is that while regional (city, state, and country) identities are cool, not everyone experiences nationhood the same way—diasporic Jews and indigenous people arguably have a betwixt-and-between status in common.

*

Maybe there’s no junior league near you. Alas. You can still introduce your kid to the ever-growing world of derby lit for little readers.

For the youngest, there’s Roller Derby Rivals by Sue Macy, illustrated by Matt Collins. It’s the true story of a 1948 armory bout and the (manufactured) rivalry between Toughie Brasuhn and Gerry Murray. Toughie (4-foot-11 and muscular, described by one newspaper as resembling Erich von Stroheim, “but uglier”) played the bad girl, the heel. Gerry was the beautiful blond star. They pretended to scrap for the cameras, but in real life, they were great friends. The book offers a great opportunity to talk about media manipulation, sexism, and female athleticism with kids. Wish the art were more appealing, but hey, life’s tough(ie). (Ages 5-9)

The undisputed champion of the derby-kid genre is the graphic novel Roller Girl by Victoria Jamieson, herself a derby skater (derby name: Winnie the Pow) in Portland, Oregon. It’s sensational: beautifully drawn, sweet as heck, a portrait of the complexities of female friendship. At junior derby practices, you see well-worn copies strewn among the street shoes, backpacks, and mouthguard cases on the bleachers. (Ages 9-13)

Falling Hard is the first in a four-book series by Megan Sparks about a small-town Illinois team called the Liberty Belles, and a new girl from London who joins the squad. There are cute boys and drama. (Ages 10-14)

Trish Trash: Rollergirl of Mars by Jessica Abel is the first book in an imaginative graphic novel series with a nonwhite protagonist and a dystopian sci-fi bent. (Ages 12 and up)

Slam!, illustrated by Veronica Fish, a former LA Derby Doll (derby name: May Q. Holla) who co-wrote Moana and wrote Ralph Breaks the Internet, is a graphic novel duology. The art’s deliciously detailed and vibrant and there’s racial and size diversity, but it’s a bummer that there’s no queer representation. (Ages 12 and up)

*

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.