A Binding Legacy

How the arc of my father’s life led me to study the story of Isaac

Here is a story:

An aged father and his son are making their way up the slopes of an isolated mountain. The father carries the implements of ritual destruction—fire and knife—and the son shoulders the material for building, but also for burning. The father, stooped under the burden of age and the weight of sacred duty, proceeds in silence. He patiently answers the son’s questions, which pierce the air and, for a moment, the father’s conscience. Then the silence closes over father and son once again, and they go on.

The nameless narrator of the story has already informed us that the father is responding to a decree: A deed without recompense is to be executed at a destination without a name, revealed only once the journey has begun, once faithful readiness has been shown. The father proceeds but delays, obeys but resists: Embedded in his obedience are signs of pain and protest, of fealty and fear. The son is observing his father’s actions and his bearing, taking in the father’s fatalism about the sacrificial object, which is either missing or, perhaps, terribly present. The father looks for signs of the destination, and in doing so, conveys signs of his own to the son.

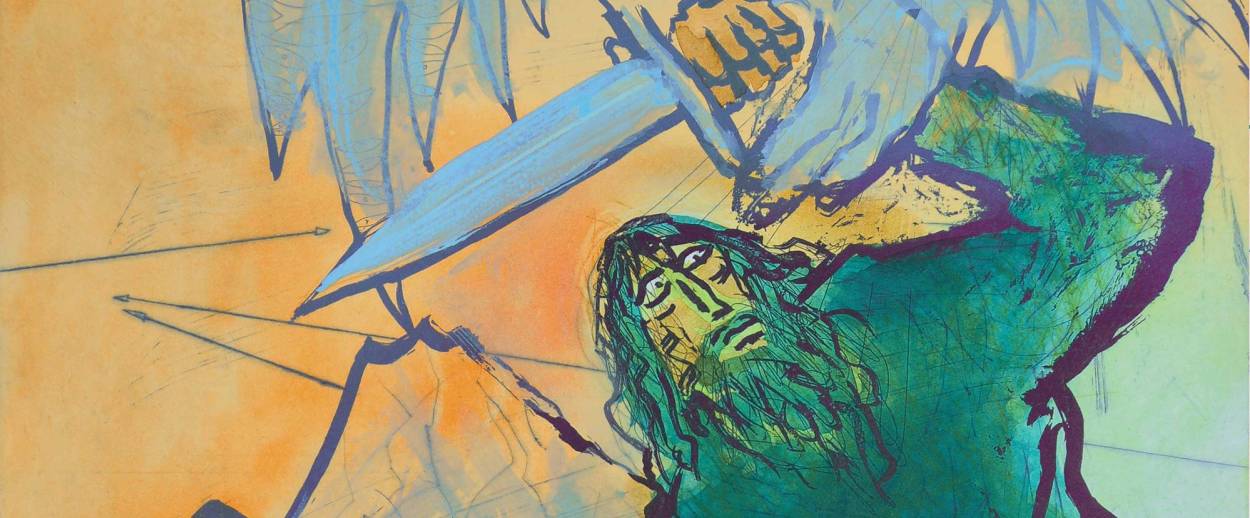

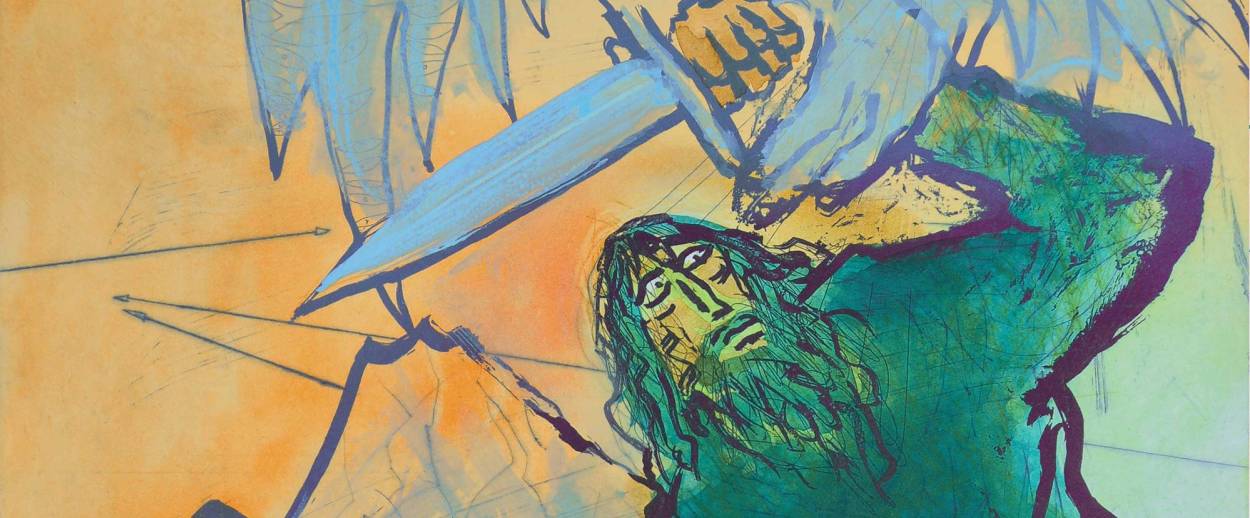

The sign is given, the altar is built, the victim is bound. At the instant at which the knife is raised—Genesis 22:10, the exact center of the 20-verse narrative of the Binding of Isaac—the story transforms itself from an act of human sacrifice to one of divine intervention.

Here is another story:

My father and his beloved younger brother, coming of age as the world was coming apart, crossed from Detroit into Canada in late April 1941, and attempted to volunteer for the Royal Canadian Air Force. According to my father, they were patted on the head and sent back across the border. In time, both men enlisted in the U.S., my father winding up in the Army Signal Corps and my uncle in the Navy as a fighter pilot. In February 1943, shortly before my uncle’s 23rd birthday, the braking mechanism on his Brewster Buccaneer malfunctioned during a training exercise, and he died when the plane plunged into a water-filled ditch at the end of the runway in Vero Beach, Florida. He was knocked unconscious and drowned before rescuers could reach him.

My father and mother rushed from Tampa, where my father was stationed at the time, to the naval base where the fatal accident had occurred. He and my mother escorted his brother’s body back home on the train to Chicago, my father riding north with the casket in the increasingly frigid baggage car, dressed in uniform, clutching a bottle of Jack Daniel’s.

Though the tragedy occurred 16 years before I was born, I saw that it had torn a hole in my father’s heart. He could not speak of his brother without the tears beginning to flow, and he hated seeing or being subject to such displays of raw emotion. He also did not want to confront death in front of his six children.

What do these stories have to do with one another?

I spent 10 years pursuing the answer to this question.

In 2008, already in my late 40s, I went back to school. I was accepted into the M.A. program in divinity at the University of Chicago Divinity School, and in 2010, into the Ph.D. program in the history of Judaism (I received the degree in 2018). I focused my research on the Binding of Isaac story from the book of Genesis, and its decisive influence on the shaping of Jewish cultural memory. I felt that the near-sacrifice of Isaac by his father was in a sense Judaism’s most misunderstood story, but I came to understand that it was also woven into Jewish DNA, and indeed into the story of my family. The Binding of Isaac is the story of all men sent to war by their elders, all women excluded from the making of such decisions, and all children exposed to trauma. My uncle’s death caused something to die in my father, but something to be born as well: a determination to live a second life, much as Isaac seems to do after the angel of God stays his father’s hand.

*

The Binding of Isaac story is ancient. Although biblical scholars have not reached consensus on its origins, age, or editing, the story probably dates from no sooner than the 8th century BCE, is probably the work of more than one author, and likely reached its final form after hundreds of years of transmission, transformation, and redaction. What’s more, it bears distinct similarities to myths and stories from neighboring cultures—stories about young boys sacrificed to the gods. In many of these stories, the ashes of the sacrificial victims are buried under the altar upon which they were sacrificed, a fate that the rabbinic sages imagine may have occurred to Isaac. After all, at the end of the terse, terrifying narrative, Isaac does not return with his father to his servants. The rabbis ask: Where is Isaac? They imagine many outcomes: He is studying Torah, he is hiding from his father—or he has been turned to ash and buried under the altar. Even more astonishing: Gravely wounded by his father, he is imagined as being spirited off to heaven by the angels, there to be healed before being returned to earth to meet Rebecca, his bride-to-be. (The possibility that he was killed and resurrected is also considered, and eagerly taken up by nascent Christianity as a harbinger of Jesus’ death and resurrection.)

Studying rabbinic commentaries on the Binding of Isaac helped me see Judaism from a radically new perspective: In rabbinic midrash, the daringly creative readings of biblical text, the rabbis at once protest against and reimagine God’s most incomprehensible, even indefensible actions. But the story also helped me see my father in a new light: as a man over whom the knife of war (and, later, invasive surgery) had flashed; as someone who had lost a part of himself; and as a person determined to wrest meaning from the potentially meaningless.

Interpretations of the story of Isaac’s binding so often focus on Abraham that the miracle of Isaac’s lifelong response to it—as a loving husband, a peacemaker, and a phenomenally successful agriculturalist—is often overlooked. But Isaac is a key for our time: He epitomizes the lack of agency we hesitate to confront in our lives, and the contradiction between our helpless repetition of parental patterns and the seeming randomness of our encounters with death. Innocence ends when we are forced to confront our vulnerability, a crisis that often occurs at the hands of those who guide us up the mountain. Then, in the flash of a knife, we understand that our time is short, and that we are on our own. Through a ritual of violent initiation—often enacted accidentally, or without our consent—we are given new vision and new scars. If we are blessed, we get to go on, but we do so shorn of the illusion that those who raised us can protect us from the terror of being an animal conscious of its own mortality. As the Israeli poet Haim Gouri wrote, Isaac’s offspring “are born with a knife in their hearts.”

I was not scarred by my father—not any more than most of us—but as a child, I was kept at a certain distance. I was keenly aware of how difficult it was for Dad to be emotionally open with his six children, and especially his two sons—until, that is, his emergency heart surgery at the age of 67. After barely surviving the procedure, he went on to live another 30 years, having emerged from his scrape with death more emotionally expressive, more loving, and, like the visible scars of his surgery, very present.

Prior to that, my father was exasperated with how complacent we were, how comfortable he had made us. His most frequent (or at least best-remembered) admonishment was, “Show some initiative!” As a child, I was too young to know what “initiative” meant, and too scared to ask. Later, I understood it to mean: “Go out and live! Be yourself! Do something!” It took until my late 40s to metabolize this directive. My siblings and I had been raised with very little Jewish education. It became clear to me that there was a vast reservoir of meaning and history wound into us with which we were almost completely unfamiliar. The initiative I showed was to deepen my understanding of Judaism—ours, my own—as much as I possibly could.

*

The Israeli novelist A.B. Yehoshua has provided a condensed restatement of the Akedah—a restatement that preserves the story’s awful suspense but provides it with an ethical urgency driven by human devotion to the divine:

Abraham conceived a new faith in a new unitary god, “the possessor of heaven and earth.” To that end he broke the idols in the home of his father Terah, and left his homeland to proceed to a new land where he would establish his offspring who would be his posterity and perpetuate his belief. But as his days drew to a close he was not certain that his son Isaac would maintain his faith. In certain circumstances Isaac might repeat what Abraham had done to his own father, abandoning the belief of his forefathers and leaving home. How could Abraham guarantee that Isaac would not only maintain the line but preserve his new belief? He stages an akedah, taking his son to “one of the mountains” (Bereshit 22). He binds Isaac, brandishes a knife over his head and drops it at the last moment. He says to Isaac, Behold the God I believe in forbade me to kill you. It was He who saved your life.

From that time on, Isaac knew that whether he believed in him or not, he owed his life to his father’s God. This is the meaning of the often repeated expression pakhad Yitzhak—Isaac’s dread. Out of Isaac’s terror of the knife held over his head was born his existential affinity (far more potent than any intellectual link) to God who would always deliver him at the last moment.

Yehoshua helps us view the Binding of Isaac not as a response to divine command, but as what Ernest Becker called a causa sui or “immortality” project: a pursuit undertaken to ensure one’s lasting legacy, and to counter the finality and inevitability of death. Isaac, though freed, remains bound: to his father’s God, to the reverberations of the act which that God had decreed, and from which Isaac, at the last instant, had been delivered.

*

Dad was a lifelong agnostic. What he did believe, though, was that he had a solemn responsibility to be gratefully aware of living. This was his ongoing memorial to his brother, and this he did more fully than anyone I have ever known, especially in the 25 years of his long retirement. He spent most of those years in southwest Florida, to which the family had been retreating since the mid 1950s, when my mother needed time in a warm climate to recover from polio. Once permanently settled there with my mother, my father fashioned a daily life of mental stimulation, physical exercise, time in nature, environmental advocacy, and the building of a broad and varied social network. He did not have an immortality project. He just cared about living. He wrote a poem about this after being released from the hospital, after a bout of pneumonia, just after his 97th birthday. Its first lines:

Now that I’ve reached the age of ninety-seven

Am I heading toward or just departing heaven?

Its last lines ended with these words:

Life and love are what you make it

So reach out, hug it, cherish it, take it!

Having lived more than half a century with the scars of an incommensurable loss, and through the death of many others he loved, my father nonetheless became, as he aged, a distinct model of how to live: always curious, welcoming, funny, engaged, and disciplined. Through a divorce, several career changes, remarriage, the joys and challenges, I had lost precisely these qualities, whereas the older my father got, the more he embodied them. It was in the pursuit of these qualities that I engaged in my graduate studies. And while my father didn’t live to see me earn my Ph.D., he did tell me, shortly before the end, that he was proud of me. I earned one of his trademark booming laughs when I said, “I know, right? I finally showed some initiative!”

*

On a warm February morning, some months after my father’s death, my mother, her six children, and several grandchildren chartered a boat for a ride in Estero Bay, the estuary where we had all joined my father on fishing expeditions for decades. It was near high tide on a warm, clear day. One by one, my father’s children, grandchildren, and children-in-law turned scoopfuls of my father’s ashes into the shallow bay as our rental boat trolled slowly across a flat where he had fished for decades.

In this, and in the roots of the mangroves, in the bellies of the descendants of fish he caught and released, perhaps something of him persists. This, too, is midrash. But in this, too, he is present, vivid, and, at last, free of the sacrifices of old men burning with a sacred fever; alive, and with no knife in his heart.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

David Gottlieb earned his PhD in the History of Judaism from the University of Chicago Divinity School in 2018. He is author of Second Slayings: The Binding of Isaac and the Formation of Jewish Memory.