Living the ‘Goods Life’

Appliances. Electronics. Television sets. New Cars. How corporations marketed to Jewish consumers, and how those new creature comforts divided the community.

Come Sept. 22, many of us will be glued to our oversize television sets rooting for The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel to take home a cluster of Emmys. While the show’s appeal is lost on me, some of its fans, I suspect, are drawn to the series by its period pieces as well as its punch lines.

Defined by its material coordinates, the universe Mrs. Maisel inhabits encompasses a really nice apartment and furniture that matches, tip-to-toe color-coordinated ensembles by the closetful, snazzy cars, and abundant food. American Jewish families like hers liked their creature comforts.

And still do. While I’m unaware of any contemporary statistical studies that take the measure of prosperity within American Jewish circles by zooming in on how many television sets, cars, and digital devices are to be had, anecdotal and impressionistic evidence (just take a look around) strongly suggests that these and other appurtenances of modern life are thick on the ground.

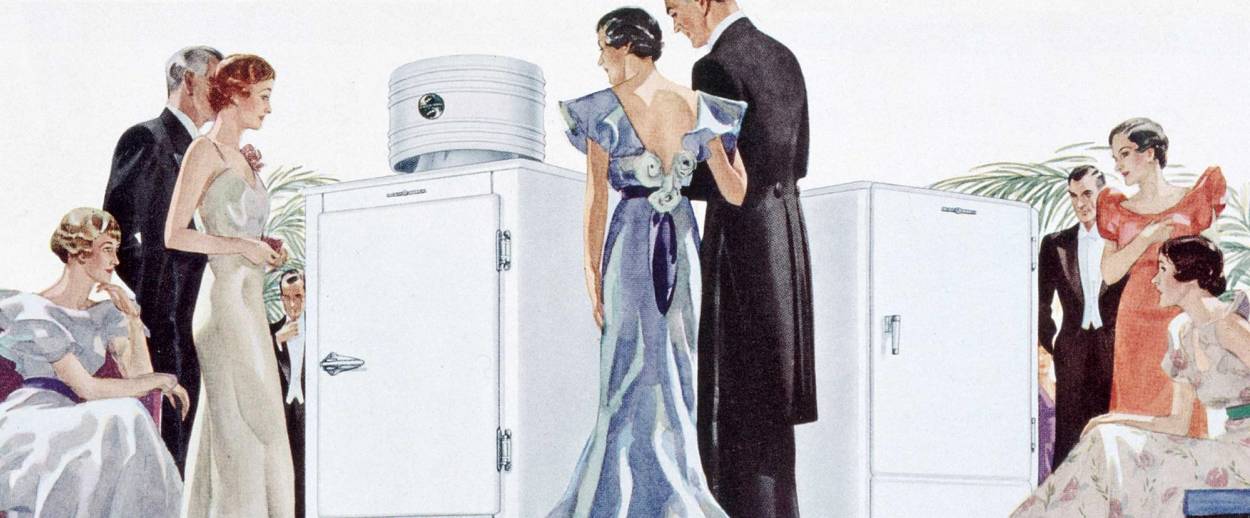

Years ago, those who kept an eye on the budding affluence of East European Jews and their offspring often applauded their embrace of technological innovations such as phonographs, refrigerators, washing machines, and cars. One of the most enthusiastic, if not the most curious, of cheerleaders was the Jewish Daily Forward, the Yiddish daily whose politics veered well to the left of its endorsement of the “goods life.”

In a heavily orchestrated attempt to court advertisers to its pages, the newspaper, in 1927, published a nearly 50-page pamphlet, “The Fourth American City—The Jewish Community of New York,” in which it characterized the Jewish consumer as a big spender. When it came to food, the Jews of New York, this self-styled “book of facts” observed, expended more than twice as much as the entire population of Detroit, Boston, or Cleveland. But food wasn’t the only commodity the Jews of New York held dear. “For every kind of wearing apparel, from garters to overcoats, for furniture and furnishings, including pianos, rugs, vacuum sweepers, washing machines; for miscellaneous commodities running from corn plasters to wrist-watches, the Jews of New York in the aggregate spend more than the populations of Detroit, Boston, and Cleveland,” the text noted approvingly.

Filled with enough quantitative material to delight a statistician, “The Fourth American City—The Jewish Community of New York” also made sure to publish a detailed list of its advertisers, whose ranks included Victor Talking Machines and Columbia Phonograph; Chevrolet, Dodge, and Hertz Drive-Ur-Self Cars; Simmons Beds, Ingersoll Watches, Tru-Pedic shoes, and Lord Salisbury Cigarettes.

That so many advertisements from so many companies filled the Forward’s pages was no isolated phenomenon, a testament to the newspaper’s standing and the smarts of its marketing staff. Much the same could be said of other American Jewish newspapers. They, too, accommodated a wide range of advertisements for newfangled consumer products.

Full-page, fancy spreads for automobiles, for instance, appeared in the American Hebrew throughout the 1920s. Some extolled the virtues of the “silent” and “agile” Packard car, others the benefits of the “economical” Chevrolet and still others the appeal of the fancifully named Locomobile, reportedly “the best built car in America.”

Boston’s Jewish Advocate, in turn, featured the Rosen Phonograph Sales Company, whose array of technological goodies was so ample that it supplied “everything but the audience.” By the 1930s, when electrical appliances—refrigerators, washing machines, and vacuum cleaners—became increasingly affordable, the weekly featured advertisements in which General Electric unabashedly crowed that “electricity is the modern Lincoln. General Electric is the modern emancipator.”

A testament to America’s bounty, as well as the benefactions of modernity, these technological innovations were hard to resist. Many Jews, succumbing to their rhetorical promise of convenience and liberation, of pleasure and contentment, were quick to fill their homes with them.

Take sound recordings and the phonograph (or the gramophone; back in the day, the terms were used interchangeably). Immigrant Jews, especially those homesick for the old country, relished the brand new medium of cantorial records. They took it on faith that just by listening, their “troubles will disappear, you will forget your cares, and every corner of your home will become lively and happy”—or so a 1918 advertisement from the Columbia Gramophone Company promised.

Not everyone, though, succumbed to the hype. Some Jews were suspicious, even contemptuous of the new medium—and of modernity’s blessings, too. The storied Odessa cantor, Pinkhas Minkovsky, was famously among them, deriding the phonograph as a “disgraceful shouting-machine” and lamenting the ways in which cantorial recordings debased and subverted the traditional Jewish liturgy, much less its rightful place in the synagogue. “Slikhot, tekhines, and kines vulgarize themselves in the confines of the gramophone,” he declared, referring to the age-old supplications.

The subsequent debut of new acoustic technologies like the microphone further complicated what constituted sacred space and sound. Thanks in large measure to the phonograph and long-playing records, a new “culture of listening” came into being by the interwar years, sharpening the ear and accustoming it to a cleaner, more controlled sound, both within and without the home. As “Technically American,” a vivid Ph.D. thesis written by my student Tamar Rabinowitz points out, increasing numbers of American Jews came to expect “good acoustics” even when attending synagogue services and sought to act on and fulfill those expectations when building a new house of worship.

Noise in the sanctuary was no longer to be tolerated, nor, for that matter, was struggling to hear the rabbi or the cantor’s voice. Brandishing about highfalutin technical terms such as “optimum reverberation” and “uniform sound distribution,” congregants at the grassroots looked to the microphone, an electrical device, to set things right and enhance the service.

Reform Jews, who used electricity and drove to temple on the Sabbath and the Jewish holidays as a matter of course, had no problem introducing the sound-amplifying system into their sanctuaries. Conservative Jews soon joined them. Having sanctioned driving to services on the traditional day of rest in 1950, the Conservative movement readily made its peace with the microphone, drawing on the same internal logic that drove its decision-making process about the car.

Orthodox Jews, though, found themselves in a real bind. How to satisfy the aural needs of the congregation while remaining true to Halacha, Jewish law, which, on Shabbos and yontef, prohibited the use of electrical devices such as the microphone? Nothing less than the future of Orthodox Judaism seemed to be at stake. If its adherents didn’t properly attend to sound and sanction the use of a microphone in the sanctuary, they ran the risk of losing members to the Conservative synagogue down the road. But if they did legitimate its use, they ran the risk of violating Jewish law and with it, sullying the integrity of Orthodox Judaism. What to do?

At first, in 1940, the Rabbinical Council of America, the official representative body of the modern Orthodox rabbinate, declared the use of the microphone permissible, provided the device was turned on prior to the Sabbath. But that imprimatur was formally rescinded a decade or so later, in 1954, and the microphone completely banned in Orthodox congregations. Little less than a decade after that, in the early 1960s, the issue was revisited and the Orthodox position even more firmly, and unequivocally, enunciated.

Writing in Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought, Immanuel Jakobovits, then the rabbi of the Fifth Avenue Synagogue in New York, clarified what was at stake. Whether to deploy a microphone for the purposes of prayer didn’t just ride on the “distinction between a natural echo and artificial amplification” or on what constituted electrical currents and discharges. Rather, it had to do with something far greater still, the existential threat posed by the “increasing mechanization of life.”

By eschewing the microphone and other “push-button devices,” he went on to explain, Orthodox Judaism held the “tyranny of automation” at bay, making it possible for worship to remain a “purely personal” experience.

A number of Orthodox rabbis who, relying on the 1940 decision, had installed a microphone in their sanctuaries, were not pleased by either the tone or the substance of their colleagues’ remarks, which they found dismissive. Making known their collective displeasure in a subsequent issue of Tradition, they insisted they were “not acting out of a disregard of, nor contempt for, Halakhah.” On the contrary, they had “good halakhic authority to support their position.” All they asked was to be accorded a measure of respect and to be counted as members of the fold.

That didn’t happen, resulting in an intra-Orthodox split between those who davened in a shul with a microphone and those who did not. Even today, when an Israeli company has devised a transistorized form of microphone, few Orthodox congregations have availed themselves of it, leaving the divide intact.

In the long run, the use of a microphone not only pitted one Orthodox Jew against another, it also differentiated, and set apart, Orthodox Jews from their non-Orthodox coreligionists, accentuating already existing fissures within the broader Jewish community.

A mixed blessing, technology generated problems as well as opportunities. Though often likened to a “fairyland,” thanks to its ability to ease the lives of its users, it just as often bedeviled them. More of a boundary marker than a form of social cohesion, technological innovations, not surprisingly, became the stuff of many a comic routine—of light bulb jokes and japes about synagogue parking lots—some of which became grist for the mill of Mrs. Maisel’s real-life counterparts.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.