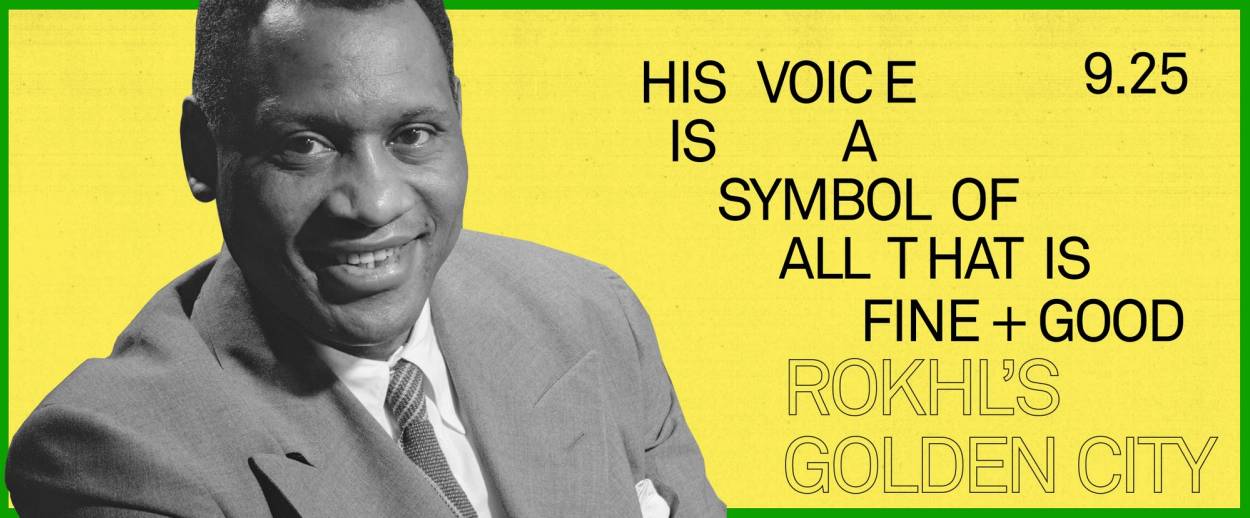

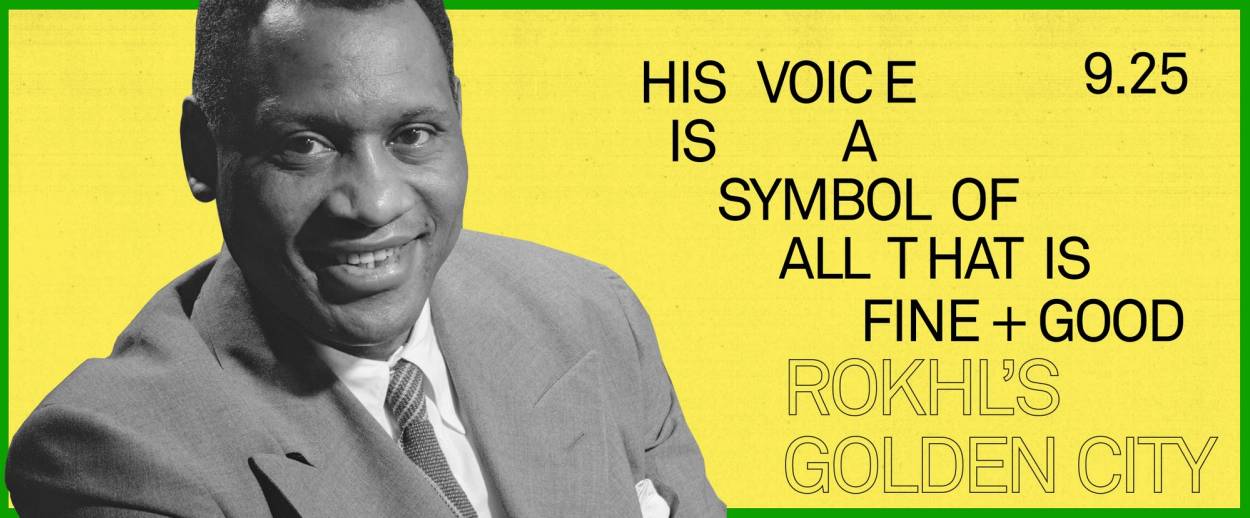

Paul Robeson Goes to Summer Camp

Rokhl’s Golden City: Remembering the legendary singer’s summer at Camp Kinderland

In 1949, Paul Robeson was probably the most famous African American man in the world. The son of an escaped slave, his life was marked by an affinity for the exceptional. This year marks the 100th anniversary of his graduation from Rutgers, where he was the third African American man to attend the school. At Rutgers he was a star football player and student. He went to law school but left the law to focus on his performance career, where he established himself as a serious actor and electrifying singer. The role of Joe in Show Boat was written specifically for him, and he opened the London production in 1928.

p

At one time, Robeson was praised as “America’s Number One Negro.” By the end of the 1940s, though, that fame was also in large measure infamy, due to his outspoken support of the Soviet Union. In April 1949, he spoke at the Paris Peace Conference; then, shortly after, he performed for thousands in Moscow. In each place his outsize presence reverberated with historical and personal impact. On his return to the United States, Robeson found a furious backlash against him, sparked by anti-American remarks he supposedly made in Paris. His livelihood was almost immediately decimated, and he was facing public death threats.

August 1949, however, found Robeson at a peaceful summer camp in upstate New York, where a basketball court was dedicated in his honor. This visit, too, had its historical import.

Camp Kinderland wasn’t just any camp. It was the Yiddish-oriented children’s summer camp of the communist-affiliated Jewish People’s Fraternal Order. Camp Kinderland was one point on the map of what writer Joel Feingold calls northern Westchester’s “red summer belt.” This cluster of summertime activity, Feingold wrote in Jacobin magazine, “had become a kind of Borscht Belt for New York’s working-class radicals. The colonies and socialist summer camps also attracted black radicals and many fellow-traveling liberals.” As Feingold noted, the political mix included communists, socialists, labor Zionists, and more.

Just a few years later, however, the organized Jewish communist world was all but wiped off that map. After considerable effort by the government, the JPFO’s parent organization, a fraternal benefits organization called the IWO (International Workers Order), was liquidated by New York state. (Camp Kinderland was found to be independent of the IWO and spared liquidation.) Long before that, though, the Peekskill Riots signaled a hostile ending to the history of the IWO and other sites of Jewish communist organizing. On Aug. 27, Robeson was supposed to headline a fundraising concert in Peekskill for the Civil Rights Congress, but mob violence, incuding local KKK, forced organizers to reschedule to Sept. 4. The second concert came off without incident, but at its close, another mob attacked concert goers, leaving over 140 seriously injured.

“Ku Klux Klan activity in Peekskill, just an hour north of New York City, was nothing new,” notes writer Jennifer Young. “[L]ocal groups protested Catholic presidential candidate Al Smith in 1928, and every few years they organized a march against an assortment of perceived foes. … But none of the concert organizers had imagined the kind of violence they would face.” Exactly 70 years ago, anti-communist panic became a pretext for what looked a lot like an American pogrom: “Protestors broke off pieces of a nearby fence and swung them at the men facing them, screaming, ‘Kill the n******, kill the kikes, kill the communists.’”

But on Aug. 14, the world didn’t look quite so bleak. Though the camp was under high security due to threats of violence against Robeson, the children, and adults, of Camp Kinderland received Robeson with adoration and hope. As controversial as he was in the American press, at Kinderland Robeson was imagined as a cross between Superman and Moses, an all-American internationalist hero.

The camp issued a special issue of its journal in Robeson’s honor. Young shared her archival research with me, including the Kinderland journal.

A typical message from the camp’s children read:

Paul Robeson iz gekumen in kamp kinderland dem 14tsn oygust. Zayn shmeykhlendik ponim un zayne eydele oygn, shteyt er far ale mentshn vos kempfn far gerekhtikayt un sholem.

Ikh denk, az ale mentshn darfn zayn shtolts mit im. Er iz eyner fun di faynste un talantfulste mentshn af der velt. Zayn shtime iz a simbol fun alts vos iz gut un fayn.

(Paul Robeson came to Camp Kinderland the 14th of August. With his smiling face and his gentle eyes, he stands for all men who fight for justice and peace.

(I think that all men should be proud of him. He is one of the finest, most talented men in the world. His voice is a symbol of all that is fine and good.)

Esther Fridman, Bungalo 25

The first page of the journal was a picture of Robeson, with the caption “Undzer Paul Robeson” (our Paul Robeson.) That feeling of intimacy, shading into ownership, was tangible for the kind of Jews who populated the “red summer belt.” When the New York school system was threatening to kick the JPFO after-school program out of public school buildings, Robeson joined them on the picket line. At least according to Ray Fireman, bunk 18, as recorded in the Kinderland journal.

Perhaps because of his many intimate connections with Jews and Jewish life, Robeson’s reputation as an interpreter of Yiddish song looms large. He sang in dozens of languages and there is a case to be made that, as a byproduct of his 1950s era immersion in global folk musics, he literally invented the American concept of “world music.” But when it comes to Yiddish, his repertoire really only consisted of a handful of songs.

One of those is his version of Rebbe Levi Yitskhok of Berditshev’s “Din Toyre mit Got” (Lawsuit Against God), also known as “Kaddish of Levi Yitskhok.” Robeson’s version is often confusingly titled as “Hassidic Chant” or simply “Kaddish.” It’s probably my favorite of Robeson’s Yiddish songs, and, to get technical about it, it’s actually an English translation of the Yiddish. But, oh my, what a translation it is.

When I read about Robeson’s rapturous reception at Kinderland, I think of him singing “Din Toyre mit Got.” His image was that of a modern day Levi Yitskhok, a wonder worker with a hotline to God—a God they probably disavowed, but nonetheless—an almost superhuman intercessor on behalf of the Jews:

A good day to thee Lord God Almighty

I, Levi Isaac son of Sarah from Berditchev

Here am I before thee

With a grave and earnest plea for this my people

What hast thou done to this thy people

Why hast thou so oppressed this thy people

And I, Levi Isaac, son of Sarah from Berditchev

Declare from my place I will not move

I will not move from my place

and an end let there be

To all the sorrow and suffering

Yisgadal v’yiskadash shmey rabo

Robeson’s history with “Kaddish of Levi Yitskhok” goes far deeper than the American Jewish desire for a secular savior. In his article “Performing Black-Jewish Symbiosis: The ‘Hassidic Chant’ of Paul Robeson,” historian Jonathan Karp argues that Robeson’s long history with the song owes less to his Jewish friends and audiences and more to his own religious feelings, and his relationship to his late pastor father. Indeed, Karp says his earliest performance of “Kaddish of Levi Yitskhok” dates to 1938, in Neath, Wales!

Karp describes Robeson’s thought processes around the song: “If Robeson’s father had learned the cadences of speech from the Hebrew Bible, the Jews themselves comprised one of the cultural and genetic sources of the Afro-Christian community and its music. Robeson’s investigation of Hasidic melody was therefore an affirmation of his father’s heritage as well as a recovery of the deepest sources of his own spiritual identity.” Robeson saw affinities between black “song-preaching” and the cantorial recitative showcased in “Kaddish of Levi Yitskhok.” Those natural connections meant that even Mahalia Jackson would feel at home in a synagogue: “She’s like one of the Hasidim.”

Karp is somewhat skeptical of Robeson’s narrative of musical affinities. (There’s no comment from Mahalia Jackson.) He notes that in the 1930s, Robeson played up his connection to Jews and Jewish music in the same ways that he emphasized his connections to Russian or Welsh music. Robeson courted the Jewish mainstream and for many years, the affair was reciprocal. In a 1933 interview with the (politically) middle of the road Yiddish newspaper Morgn Zhurnal-Togblat, he even claimed that he was looking to add a Yiddish opera to his repertoire. Alas, it never came to fruition.

Today, Robeson is most strongly associated with the song that was written for him, the song that changed the direction of his life: “Ol’ Man River.” And today, if you’re a striking African American man possessed of a honeyed bass vocal instrument, and you sing in Yiddish … people are going to ask you about it. A lot.

Such is the case with my friend, Anthony Mordechai Tzvi Russell. Russell, on the other hand, has chosen a very different bass vocalist as the touchstone of his Yiddish singing career: Sidor Belarsky. Having observed Russell’s Yiddish singing career from almost the very beginning, I know that he has been consistent about his admiration for Belarsky, practically shouting it from the rooftops. Yet, the questions keep coming, as well as the requests for that song. The comparisons to Robeson aren’t just othering, they highlight the tensions ever present in Russell’s life as an African American Jew in a largely white space. He is always fighting to be seen as he is, not as we want him to be.

As Russell recently told me, Robeson “presented an elevated figure of sonorous blackness upon which portions of his Jewish audience could project their hopes for a future of racial equality.” The pressures of such a performance create “a lonely and oddly hollow road, made up as it is by depictions of former modes of blackness, limited in its relationship to the issues of the present day.”

Robeson’s enormous legacy remains unsettled, and in large part, unclaimed 43 years after his death. Many aspects of his life are hotly contested, both in fact and interpretation. His failure to renounce Stalin hangs over his memory like a dark cloud. But the racism that dogged him at every step is still very much with us. The son of an escaped slave, he could become one of the most famous people in the world, and still be refused a room at the “whites only” hotels of 1940s Los Angeles.

While many still balk at reclaiming Robeson for the pioneering figure he was, I think we owe it to him to examine the tensions and prejudices that defined his life, and the complicated ways he used music to navigate superhuman challenges as an extraordinary, but flawed, human being.

MORE: Listen to this fascinating KPFA interview with Paul Robeson from 1958, a master class in how to be interviewed.

ATTEND: Rutgers University will be holding a panel discussion called “Paul Robeson, ‘Negro-Jewish’ Unity, and the ‘Jewish People’s Movement’ in the 1940s: Challenges and Legacy,” at the Douglass Student Center, Trayes Hall, 100 George St., New Brunswick. Oct. 6, 4 p.m.

WATCH: One of the best birthday presents I ever got was from my law school study group friends who got me the Criterion DVD collection of Paul Robeson’s movies. It’s worth it just for Proud Valley, but the excellent collection of essays on Robeson’s work and legacy makes it a must have for Robeson fans. … The role of the stevedore Joe was written for Paul Robeson, though he was unable to premiere it in New York. The history and racial dynamics of Show Boat and “Ol’ Man River” are complex, to say the least. You can read a good summary of the many changes made to the song, including Robeson’s own changes, here. Problematic as it was, and is, Robeson’s version of “Ol’ Man River” is too good to be left in the past.

ALSO: Division Avenue is a new short feature shot in Hasidic Williamsburg. Two women, one Hasidic and one Mexican, cross paths in the Brooklyn neighborhood’s infamous gray market for domestic laborers. Screening Thursday, Sept. 26 at 9 p.m. at Alamo Drafthouse Cinema in Brooklyn as part of the Katra Film Series, then on Friday, Oct. 18 at 11 a.m. at AMC Loews 34th Street as part of the Chelsea Film Festival. More screenings in California and further afield listed here. … Russ and Daughters: An Appetizing Story just opened at the American Jewish Historical Society. The exhibit “celebrates the legendary Jewish appetizing store’s role in shaping New York’s culture and culinary heritage.” Open through January 2020, 15 West 16th St. … Friends of the column Alex Weiser and Ben Kaplan aren’t just the public programming and education directors at YIVO, they are talented theater artists. I saw excerpts of their new opera on the life of Herzl, State of the Jews, last year, and despite my fear of the words “modern opera,” I loved it. State of the Jews is coming to the 14th Street Y this December for a limited engagement. Get your tickets now. … There’s a new Yiddish immersion program on the scene. The Medem Center is putting on its second Yiddish Marathon event. It’s a week at a Greek resort, totally in Yiddish. Sounds amazing, right? Dec. 29-Jan. 4, 2020. Details here. … This December the Folksbiene Yiddish Theatre is producing a newly restored version of Avrom Goldfaden’s Di Kishefmakherin (The Sorceress). Tickets will sell out fast. … PBS is streaming an excellent new short documentary about the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire with a special appearance by Forverts archivist extraordinaire, Chana Pollack. … Finally, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are around the corner. Over at the Yiddish Song of the Week blog, Itzik Gottesman highlights a lovely and yontev-appropriate song called “Bin Ikh Mir a Shnayderl.” The verses are in Yiddish but the refrain is from the Unesane Toykef prayer: udom yesoydo meofer, vesoyfoy leyofer (man’s origin is from dust and his end is dust). The juxtaposition of the humble tailor’s work and the solemnity of the prayer are a quintessential bit of geshmak Yiddish culture.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.