A Fraternity of Silence

One man’s fight to uncover the history of anti-Semitism at America’s dental schools

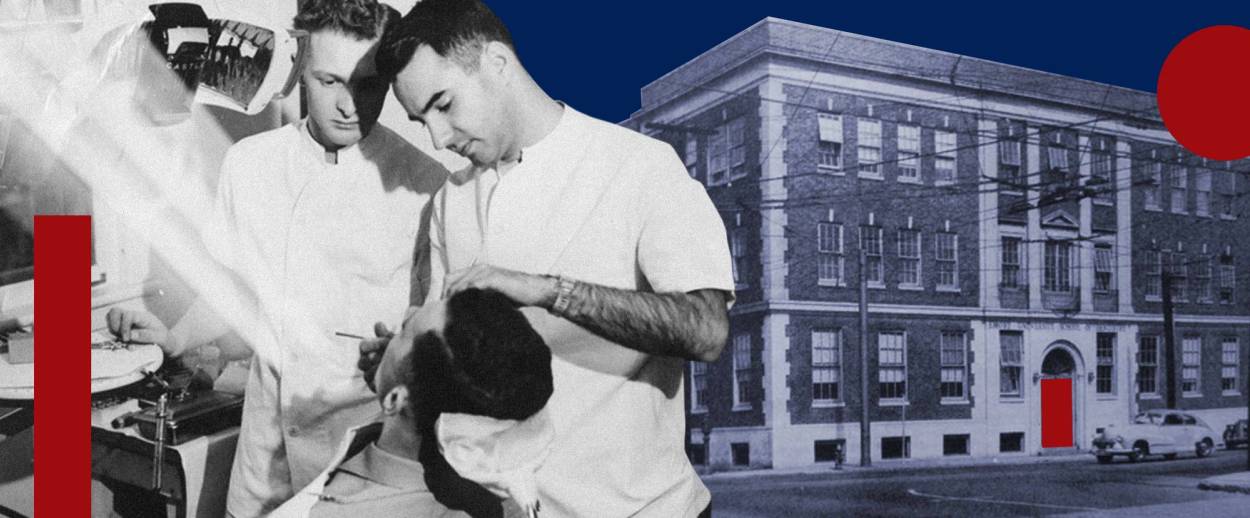

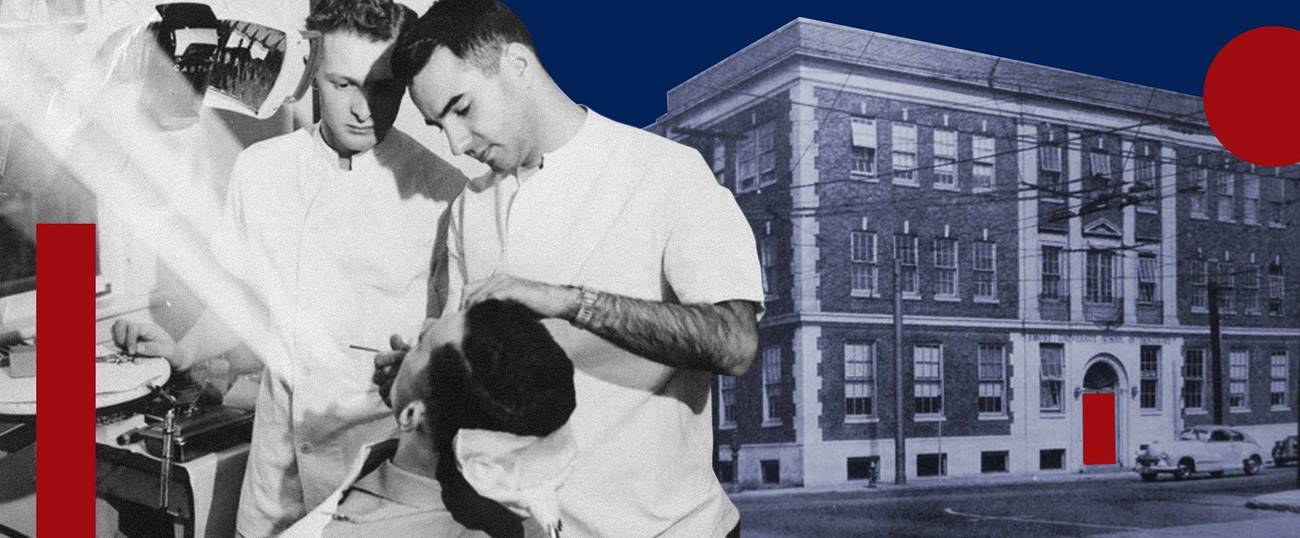

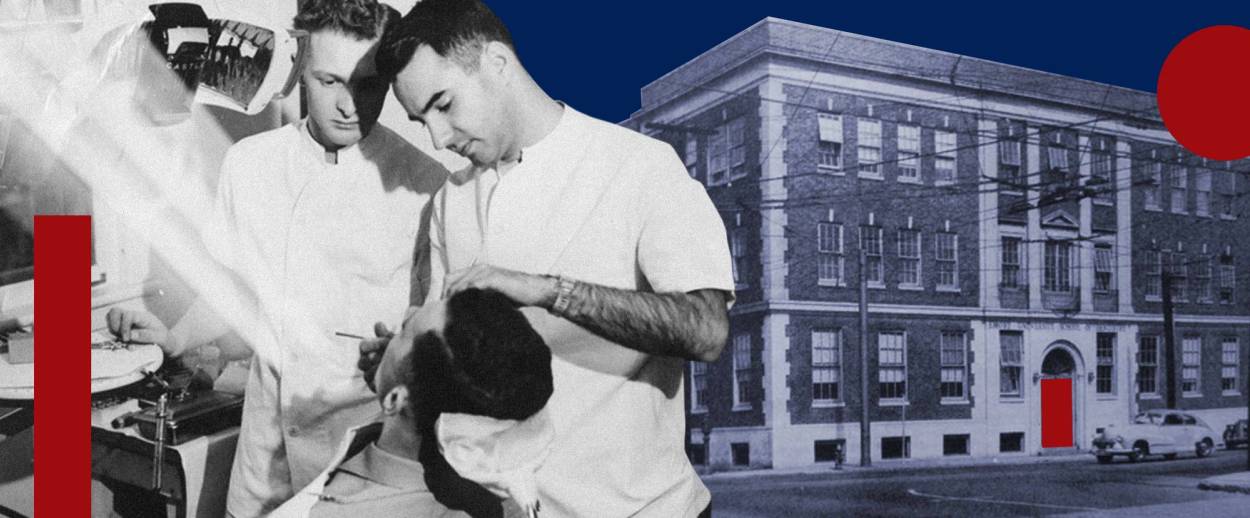

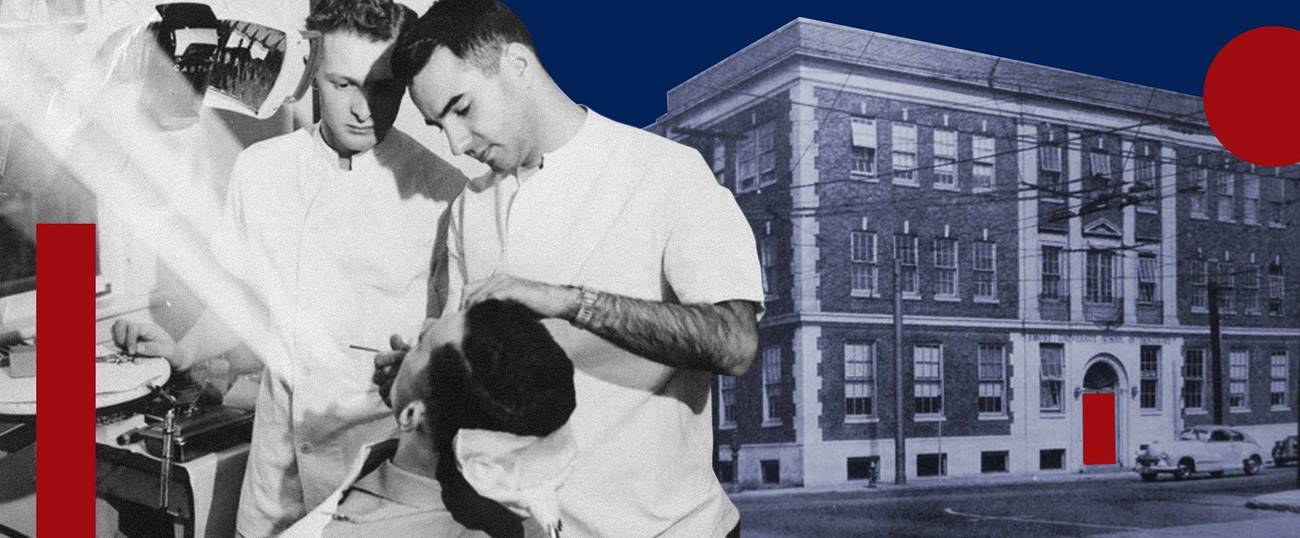

When Perry Brickman failed out of Emory University’s dental school in 1951, his parents—Lithuanian Jews whose families had immigrated to Tennessee, where Brickman was raised—were disconsolate. “My mom had worked really hard all her life,” he told me. “I was gonna be her boy! It was really upsetting to her when I flunked out. My dad got real quiet.” Brickman paused. “They did live to see me graduate from dental school with honors. But they always still thought if I’d worked harder, I would’ve made it at Emory. Unfortunately, they didn’t live long enough to hear the apology.”

That apology came from the president of Emory University in 2012. It acknowledged that Brickman and almost two-thirds of his Jewish classmates were deliberately kicked out of the school or made to repeat a year or more of their classwork. The dental school’s dean from 1949 to 1959, John Buhler, had systematically flunked them outright or attempted to force them to quit. (In the years after Brickman’s brief tenure, Buhler also amended the school’s application so that students had to check off whether they were “Caucasian, Jew or Other.”)

In Extracted: Unmasking Rampant Anti-Semitism in America’s Higher Education, with a foreword by Deborah E. Lipstadt, Brickman details how he uncovered Emory’s dental school’s history of profound bias. “There were four Jewish boys in my class,” he told me. “All four of us got kicked out. Can you imagine the humiliation? We were so embarrassed we didn’t speak for 50 years. We avoided each other. My wife called us a fraternity of silence.”

Most of the Jewish dental students who failed—“close to 100, more if you wanted to count the ones who weren’t allowed in in the first place,” Brickman said—wound up going into other fields. But Brickman was allowed, “with my hat in my hand,” to attend the University of Tennessee dental school. He graduated with high honors in 1956. He went on to co-found the Georgia Society of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, sit on the Georgia State Board of Dental Examiners, and become president of the Atlanta Jewish Federation.

In 2006, Brickman was invited to an exhibit about the history of Jews at Emory, curated by Eric Goldstein of the Tam Institute for Jewish Studies. Brickman stopped in front of one particular panel and froze. “The fifth panel was on anti-Semitism at Emory,” he said. “I was stunned. I saw a bar graph showing that 65% of us flunked out or had to repeat years, and I said, ‘Oh my God, the four of us were not the only ones.’” That graph had been made from data provided by the Anti-Defamation League in 1961. Tipped off to Buhler’s actions, the ADL had presented a wealth of evidence about Buhler’s behavior to Emory, which then compelled Buhler to resign. But Buhler wasn’t censured, and went on to other academic jobs. The story stayed quiet.

After seeing the exhibit, Brickman was determined to make sure everyone knew the truth. He visited libraries and archives all over the country and interviewed Jews who’d spent time at Emory. “People didn’t want to believe it,” he said. “But I traced it all back to the American Dental Association, my parent organization.”

In the 1940s, the ADA formed a council on dental education in an attempt to improve the field. The organization hired a consultant named Harlan H. Horner, who published a report in 1940 suggesting all the ways dental schools could do better. One important step was admitting fewer Jews.

“He wrote that 36% of the dental students come from four states—New York, New Jersey, Illinois and Pennsylvania—and those students are all from the same ‘immigrant background,’” Brickman said, the quotation marks audible in his tone. “In other words, they’re Jewish. Maybe a few are Italian. And this is not good. We need representation of all people; if you’re a dental school in Georgia you need good ol’ country boys! You shouldn’t have any Jews! Some of this made sense: He wanted students from everywhere. It sounds real good. But he obviously had an agenda.” The ADL leaked the story to The New York Times, and the American Dental Association issued a statement saying no worries; they’d never agree to Horner’s recommendations. “This was in the middle of the war, and they said Jewish boys were fighting like the other boys,” Brickman said. But the Horner commission had already approached individual dental schools urging them to take action. One of the schools was Temple; when Brickman visited its archives, he said, “I found a letter the dean of the dental school wrote to the president saying that his number one accomplishment was improving the school’s horrible physical plant, and number two was that four years ago, 72% of the freshman class was of the Jewish persuasion and now, only 24% were. They said it wasn’t anti-Semitism or anything against the Jews, it’s just that we were admitting too many students from New York state. But the number of Jews went from 72% to 24%.”

Brickman went through old yearbooks from dozens of dental schools to see how Jewish student populations changed in the wake of the Horner commission. “I looked at names and fraternities,” he said. “And if it was a name that you couldn’t really tell, but he was married to Sadie Goldberg, I knew a boy was Jewish.” Sure enough, he found that the numbers of Jews in dental schools—“even Columbia!”—plummeted. “It was a conspiracy, no question about it,” he said.

He also interviewed the three Jewish students who’d been in his class. “The boy who sat right across from me was deemed 72nd out of 72 students in the class,” he said. “He went into the service, then got into Temple, because someone knew someone who knew someone. He finished first out of 131 in his class. Another guy also joined the service and also got back into dental school. The fourth boy became a psychologist. We all had to start from scratch.” Brickman interviewed another student who was told by Buhler, “I don’t know why you Jews want to be dentists. You don’t have the hands.” Brickman said, “One of the boys became an interventional cardiologist. That certainly requires the fine use of one’s hands! It was just hatred, that was all.”

Brickman was born in 1932, but he looks and sounds like a much younger man. “For my 75th birthday my kids gave me a laptop,” he said. “They took me to the basement and there it was! They said, ‘Surprise!’ And then ‘There’s another surprise; we used your credit card!’” Brickman decided to use the laptop to make a documentary about Emory. “I went to the Apple store,” he said. “They teach you one-on-one and I got pretty good.”

His neighbor, Emory professor Deborah Lipstadt, heard about his project. “I saw her in shul and she said, ‘Why haven’t you showed me?’ Emory had just backed her at that trial, so I didn’t want to say, ‘Because you don’t have a clear enough mind to handle this! You belong to Emory!’ I said, ‘Well, I didn’t want to conflict you.’ She said ‘Look, send it to me.’ I dropped it by her house and didn’t hear from her for two weeks and thought, ‘Uh-oh.’ But then she wrote. She usually writes terse emails, not with good grammar, because they’re just emails. But this one was long and eloquent. She told me how much she loved it, my documentary. She said, ‘Right is right and wrong is wrong.’ She said, ‘You did this the right way. You were objective. This has to be a book, a movie!’ She and a few others got me in to present the documentary to the VP of Emory. He said, ‘This is not Emory.’ And I said, ‘Not now. But it was.’ He said, ‘What do you want us to do?’ I said, ‘Well, that’s gotta be up to you.’ If I’d asked for money, it would’ve sounded like a shakedown, and anyway, as one of the four boys said, they don’t have enough money to pay us for what they did to us. They ruined our lives. We’re all OK, we had good lives, but it wasn’t what we’d planned. And we still bear that burden.”

In 2012, Emory President James Wagner presented a formal apology to the people the school had harmed. “I am sorry,” he said. “We are sorry. We know that Emory can never totally repair the impact that discrimination had on Jewish dental students more than half a century ago, but we can use the opportunity provided by Dr. Brickman’s research to reflect on these events in ways that make us more vigilant.” Emory also hired a professional filmmaker to make a documentary, From Silence to Recognition: Confronting Discrimination in Emory’s Dental School History, incorporating Brickman’s source material, and showed it at the event. “You couldn’t get a parking place at Emory that night,” Brickman said. “That’s how I found out it was bigger than Emory.”

Brickman credited his friend Miles Alexander, a Harvard Law grad, former lawyer for Martin Luther King Jr.’s estate, and former chair of the Atlanta Ethics and License Review Boards (who, as an Emory freshman, had advocated with classmate Elliott Levitas for the integration of Emory’s grad schools) for pushing him to pursue justice: “Miles said that the bookends of anti-Semitism in Atlanta are Leo Frank and Emory dental school,” Brickman said. “When fear is instilled in a community, it allows evil to go unopposed.”

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.