Fifty Years of ‘Sesame Street’

The kids’ show, with its many Jewish connections, celebrates a milestone

My husband Jonathan’s two earliest memories are watching the moon landing and watching the premiere of Sesame Street. My own (very slightly later) childhood recollections include being hypnotized by Sesame Street’s 1970s trippy hand-drawn animated segments. Perhaps you, too, remember “The Madrigal Alphabet,” with those psychedelic morphing fairies and crayfish. Or “The Pinball Game,” which taught us about the number 12—sung, I learned just today, by the Pointer Sisters. Or the perky Ladybugs’ Picnic, in which those hip hippodamia “talked about the high price of furniture and rugs, and fire insurance for ladybugs.” Or what about the recurring “Jazzy Spies” cartoons, with vocals by Grace Slick and ever-shifting visuals of freaky wizards, devils, elevators, and trenchcoated creepers? Or that flower-bedecked, sitar-driven, Maharishi counting number that made us feel like tiny George Harrisons, though we didn’t even know it yet! In my family, we had to lunge for the set whenever that klutzy baker came on, because my little brother Andy would start sobbing every time the poor fellow tumbled down the stairs, splattering his five fancy fruitcakes, seven pumpkin pies, or 10 chocolate layer cakes. A sensitive soul, Andy could never be convinced the baker wasn’t hurt. Since I’m pretty sure we didn’t have a remote control yet, the rest of us had to be quick.

This year, Sesame Street turns 50. PBS, its original home, aired a celebrity-stuffed birthday celebration last weekend that, sadly, barely touched on what made it special. Yes, it was fun (if a little frustrating) to have Patti Labelle do a pastiche of snippets of classic numbers, touching to see Solange’s tribute to the classic “I Can Remember (Bread, Milk, Butter),” and meaningful to have Lucy Liu explain that the show helped her learn English. But there was entirely too much Meghan Trainor and Joseph Gordon-Levitt and entirely too little depth or grit. The few seconds of Patton Oswalt’s favorite Sesame Street memory—watching Stevie Wonder and his band play “Superstition” in 1973, on a much less manicured street than the one later generations grew up watching— felt authentic and chaotic and funky in a way nothing else in the special did. The final few seconds, in which Grover asked Kate McKinnon, “You wanna move in?” and Kate looked away, murmured a weirdly slow “yeaaaahhhh,” and curled her tongue, had more quirk and personality than the rest of the special put together.

Also, since I am bitter, the “new” voices of Count von Count, Big Bird, and Oscar made me want to cry.

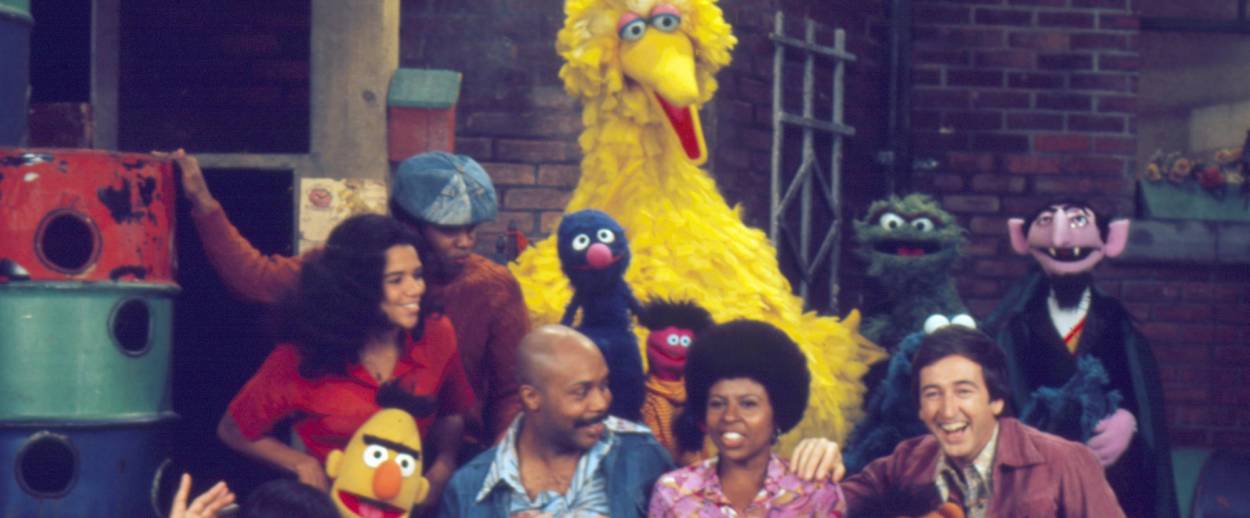

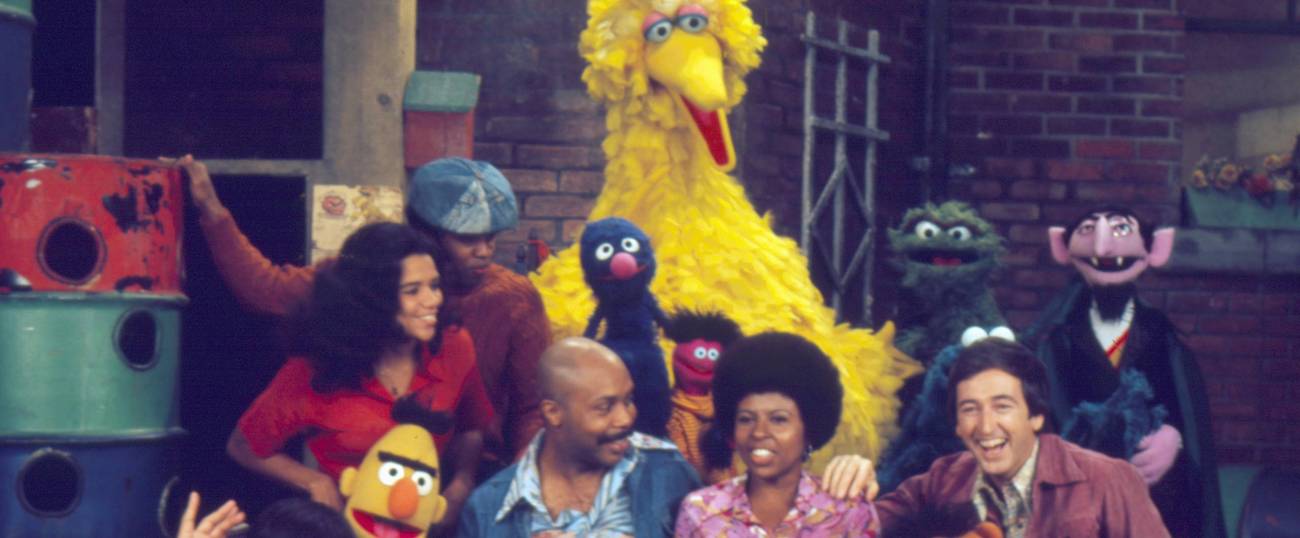

For me, Sesame Street was never about its famous visitors (though I do fondly recall Madeline Kahn dueting with Kermit on “Sing After Me”). It was about the regulars, human and Muppet, and the glory of a diverse, rundown yet homey street in which folks of all stripes could learn and hang out together.

So of course idealistic urban Jews were integral to Sesame Street’s origins. Because have you met us? Its genesis was a 1966 dinner at Joan Ganz Cooney’s apartment, attended by Carnegie Corporation VP Lloyd Morrisett and NYC Channel 13’s program manager Louis Freedman. Freedman was grumping about the lack of educational kids’ TV, and according to Michael Davis’ Street Gang, the friends asked themselves, “What if you could create content for television that was both entertaining and instructive? What if it went down more like ice cream than spinach? What if we stopped complaining about the banality we allow our children to see and did something about it?”

Cooney was the bookish granddaughter of German Jewish immigrants who settled in Arizona in the 1870s. Her father was a fervent atheist; her mom was Catholic. A former teacher, she produced a report for funders called “The Potential Uses of Television in Pre-School Education.” It advised tapping into advertising techniques and strategies to teach numbers and letters and creating programming that families would enjoy watching together. The Carnegie Corporation, the U.S. Department of Education, and the Ford Foundation donated most of the seed money for the launch of Children’s Television Workshop (today called Sesame Workshop). Harvard Ed School professor Gerald Lesser, one of the few people conducting research on kids and TV at the time, became the chair of CTW’s advisory board. He worked with the startup team and offered guidelines (including doing lots of interviews with real kids in day care and Head Start programs and revisiting shows after they aired to be sure they were meeting educational goals). In 1968, Lesser held seminars with noted writers, thinkers, academics, filmmakers, and illustrators to discuss what smart-kid TV could be. Fun fact: One of the participants was Maurice Sendak. Sendak was often bored and annoyed in the meetings, spending a lot of time drawing snarky cartoons. One doodle was titled “One Minute of Educational TV.” It depicted a calm child looking at a television, “then yawning, then sticking his tongue out at the screen,” recalled producer Jon Stone to Street Gang author Michael Davis. “The child grew more and more ferocious, hitting the set with his fist, then attacking it with a hatchet, reducing it to a smoldering pile of wires and plastic, and finally taking out his tiny penis and peeing on the whole thing.”

The original title for the show was 123 Avenue B, but it was dismissed as too New Yorky. No one loved the name Sesame Street, but no one could come up with anything better, so it stuck. The producers were clear about the human characters they wanted to launch with: A black male community leader named Gordon (after Gordon Parks), a male singer named Bob and a female singer named Susan, and a cranky old Jewish male proprietor of a corner store and soda fountain, to be named Mr. Hooper. The show hired Will Lee, a Jewish actor from Brooklyn and member of The Group Theatre (the activist company that originally produced the works of Clifford Odets and strove to make art that addressed social reform and the troubles of the common man). Lee had been blacklisted during the McCarthy witch hunts and didn’t work for over a decade. Bob McGrath, who played Bob, recalled walking on the street with Lee and seeing Elia Kazan—who’d informed on other actors to the House Un-American Activities Committee—walking toward them. Lee had to cross the street.

Sesame Street was an immediate hit, though critics derided the pace as too frantic and the street itself as ugly. Mississippi banned it because “it uses a highly integrated cast of children.” Feminist leaders publicly complained that Susan was a “just a housewife.”

Nevertheless, the show did huge numbers: It captured 1.9 million households in its second week, which was especially amazing given that the show was only in 68% of households and in some markets ran on UHF channels. Ernie’s “Rubber Duckie” number also climbed the Billboard charts.

Over the years, the show kept doing important work. In the ’80s, the episodes that addressed Mr. Hooper’s death (after the death of Will Lee) were models of how to talk to children honestly and sensitively about loss and grief. When childhood sexual abuse became a public concern, producers pondered the fact that no one believed Big Bird about the existence of Mr. Snuffleupagus (nobody else had ever seen him); they worried that kids wouldn’t report abuse, convinced they’d be shrugged off the way Big Bird was. So Snuffy was made visible. The street’s adults apologized for their earlier dismissiveness, and Bob told Big Bird, “From now on, we’ll believe you whenever you tell us something.”

The show was racially and culturally diverse from the get-go. In many ways. Writer Emily Perl Kaplin (later Kingsley), who worked for Sesame Street from 1970 until 2015, had a son with Down syndrome—she’s perhaps best known for her viral essay “Welcome to Holland”—and worked hard to ensure that the show depicted kids with special needs. Itzhak Perlman showed up regularly, using metal crutches, at one point explaining that some things are easy for him (like playing the violin) and some are hard (like climbing stairs). Today, there’s a girl Muppet with autism and sensory issues.

When Jonathan and I had our own kids, Sesame Street came back into our lives. Toddler Josie was obsessed with R.E.M.’s appearance singing “Furry Happy Monsters.” She’d bring us the TV remote (“mote!”) and point at the screen, urging us, “Monstew? Monstew? OK!” Maxie loved Aaron Neville’s duet with Ernie on “I Don’t Want to Live on the Moon” and laughed uproariously at Robert DeNiro’s (excellent!) impression of Elmo. More and more screen time seemed to be devoted to Elmo. Maxie was beside herself with joy when my mother-in-law got her a terrifying talking Elmo potty. Jonathan and I were less delighted. We privately enjoyed the video of Tickle Me Elmo being set on fire.

Nowadays, the street sometimes feels like a very different place. It’s gleaming, chirpy, full of long semifunny parodies of TV shows like Stranger Things and Game of Thrones that garner a ton of social media attention but don’t seem truly aimed at preschoolers. Cookie Monster learns about delayed gratification from Tom Hiddleston; once-snarly Oscar is practically cuddly. Mr. Hooper’s store would fit right into my ever-snazzifying East Village neighborhood; Alan, who took it over in 1998, has really cleaned it up. Everything’s pretty banal, the last thing Cooney and crew wanted.

But the biggest sign of gentrification is the show’s impending move to HBO Max. The new pay network, designed to compete with Disney Plus, will debut sometime in 2020 for around $15 a month. Since 2015, episodes of Sesame Street have aired on HBO nine months before they’ve aired on PBS, but at least they regularly ran for free. Now it’s unclear when new episodes will be on public TV (“at some point,” HBO says), which of course negates the show’s original mandate: helping less-advantaged kids catch up to their more-privileged peers in kindergarten readiness. But maybe it doesn’t matter: For years, the emphasis on teaching letters and numbers has felt as though it’s been dumped by the side of the road. Now, in addition to the extant cloyingly adorable new Muppets, theme parks, and merch, HBO Max will introduce a late-night parody show hosted by Elmo and an animated spinoff which will depict the Muppets as mecha-style robot-esque heroes. I hate to sound like the cranky GenXer I am, but this is terrible.

At least we have YouTube.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.