Open for Business—on Shabbat?

Restaurants in Israel push for changes to kosher-certification rules

On a rainy Saturday afternoon, Naama Holzman sat in a Jerusalem cafe savoring a cup of rose-flavored malabi pudding and reading a newspaper while waiting to meet a friend for lunch. Her golden retriever lounged by her feet. Nothing about the scene seemed out of the ordinary— except that Holzman is religiously observant. This would usually make going to restaurants and cafes off-limits because she would be eating food cooked after sundown on Friday, and she’d be doing things like paying and handling money—all off-limits for those who are shomer Shabbat. But this cafe, Bab al Yemen in Jerusalem’s mixed secular and religious neighborhood of Rehavia, is an exception: The staff prepares all of the food before Shabbat starts and requires customers to either pay before sunset Friday or after dark on Saturday. Tea and coffee are made with water kept hot in a Shabbat urn. Diners are offered wine and two pita breads so they can make the traditional kiddush and hamotzi at the start of the Shabbat meal.

“It’s really nice to have the option to come here, to get out of the house,” said Holzman, who lives alone. “It’s something different.”

For now, this is the only so-called Shabbat restaurant in Jerusalem. And now its owner, Yehonatan Vadai, along with the Israel Restaurants Association and an Orthodox nonprofit group, is fighting a legal battle to make the concept officially kosher.

In general, Israeli rabbinical authorities do not grant kashrut certificates to restaurants open on Shabbat, and they rejected Bab al Yemen’s application. But Vadai and his allies have filed an appeal in the Supreme Court saying Bab al Yemen has a right to kosher certification because it operates on Shabbat within the bounds of Jewish law the same way that hotels do, serving only pre-made food and paying workers the stipulated higher wages that labor laws require. And most hotels have kosher certification.

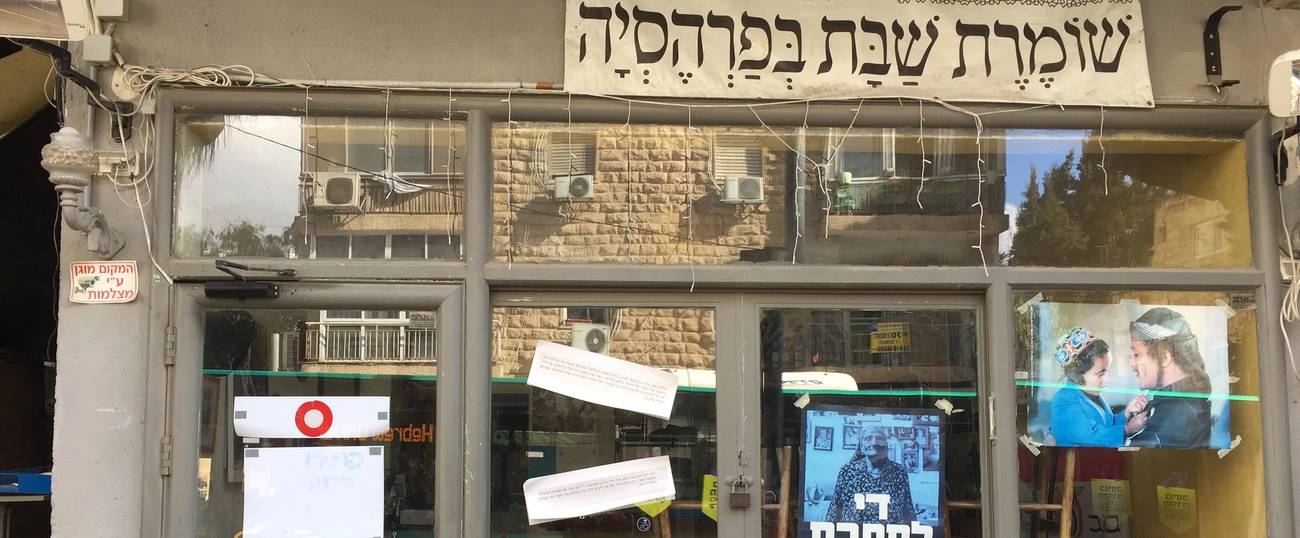

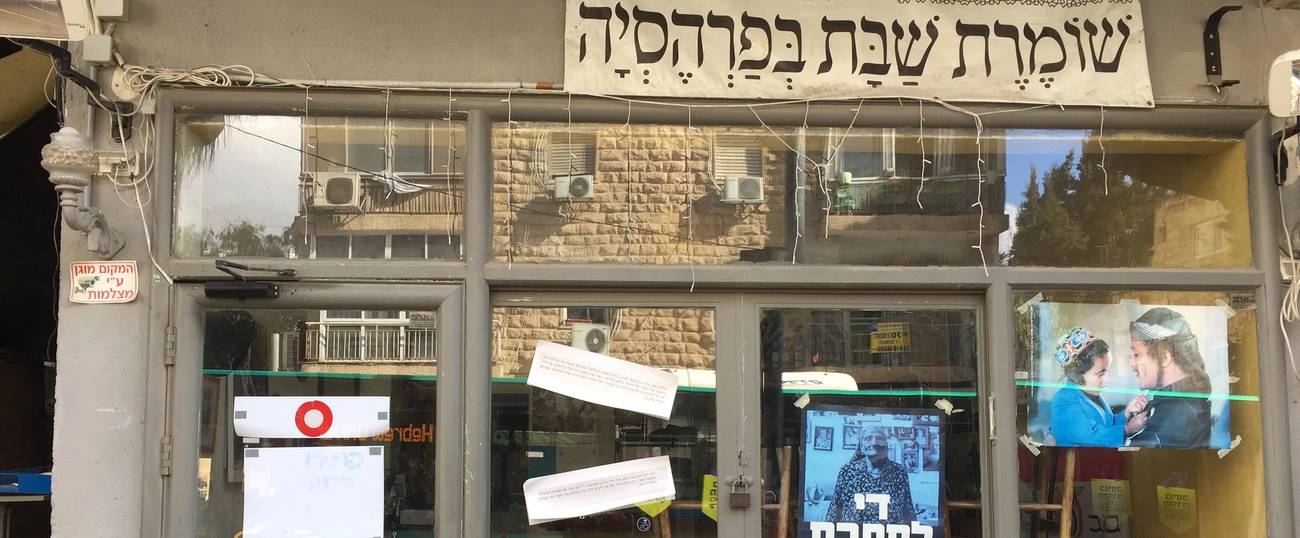

“I am not doing this just for myself, but it’s important for Judaism, and for the religious public to have places like this that work on Shabbat in a kosher way,” Vadai said. “It’s important to show that it can be done, halachically.” This mission is perhaps summed up best in a black-and-white banner that hangs above the restaurant’s door: Shomer Shabbat B’Farhesia, or “Observing Shabbat in Public.” It is a play on words from the Talmudic phrase Machalel Shabbat B’Farhesia, or “Breaking Shabbat in Public,” a grave transgression that effectively cuts Jews off from their communities.

If Bab al Yemen wins the case, it will be a game changer for the dining scene in Israel, where restaurants often forgo kashrut certification because they want to be open on Shabbat, said Shai Berman, general manager of the Israel Restaurants Association, which represents hundreds of eateries, and recently joined the legal case against the chief rabbinate. “Finally restaurants will have this option,” he said. “And we see growing demand for it: Tourists want to eat their Shabbat meals out in the city, not stuck inside their hotels, and local people, especially those who are traditional, would also prefer to sit at a kosher place on Shabbat.”

*

Bab al Yemen’s case is the latest development in increasing public pressure and litigation aimed at getting Israeli rabbinical authorities to reform their ways and better meet the needs of a modern society.

“There is much more pressure now on the rabbinate to be more flexible,” said Shuki Friedman, a law scholar and director of the Center for Religion, Nation and State at the Israel Democracy Institute, a Jerusalem-based think tank. He cites a 2018 Supreme Court ruling that for the first time in Israel’s history allowed a body other than the state-controlled rabbinate to legally certify kashrut practices in restaurants. Vadai’s other restaurant, Carasella, just across the street from Bab al Yemen, was one of the parties that filed a court case against the rabbinate that ultimately led to the legality of such alternative certificates. Now, Carasella is one of dozens of restaurants—making up about 10% of Israel’s kosher eatery market, according to Friedman—that is overseen by Tzohar, an organization of about 800 Orthodox rabbis that is best known for its work helping couples navigate the rabbinate’s strict marriage requirements, including proof of Jewish status. There are some limits; Tzohar is not allowed to use the word “kosher,” or “hashgacha,” so it gets around this by using more vague language.

“But for all intents and purposes, there is competition today in the kashrut sector,” said Rabbi Aaron Leibowitz, who started the nonprofit kashrut-certifying body Hashgacha Pratit, which in May became Tzohar’s kashrut division.

Leibowitz’s current project is trying to break the rabbinate’s monopoly on weddings by performing halachic ceremonies outside the institution’s framework.

Allowing kosher restaurants to open on Shabbat in a halachic way could be another step toward greater religious flexibility. Tzohar is also considering the possibility of supervising restaurants open on Shabbat, but for now only works with restaurants that close for Shabbat.

“Without a doubt, it’s halachically possible, and there would be a demand from tourists, or singles who don’t have elsewhere to eat,” Leibowitz said. “But there are also challenges.”

*

Outside Israel, the concept of certified kosher restaurants operating in a halachic way on Shabbat, serving prepared food that is heated rather than cooked fresh, and accepting payment ahead of time, is widespread. In places from the historic Jewish ghettos of Venice and Budapest to the modern Russ & Daughters Café in New York’s Jewish Museum, prepaying customers fill tables during Shabbat.

“It’s quite crazy that Israelis go around the world and eat kosher food in restaurants on Shabbat, but they can’t do it at home,” said Elad Luvitch, an attorney for the modern Orthodox movement Ne’emanei Torah Va’Avodah who is representing Bab al Yemen’s case in court.

Old-timers will tell you that it was once possible. In fact, tales abound about a few kosher restaurants in the center of Jerusalem that served Shabbat meals mainly to yeshiva and university students back in the 1960s, selling admission tickets before Shabbat. “And if you hadn’t purchased a ticket before Shabbat you could leave your wristwatch there,” and come back to pay after Shabbat, my husband’s stepfather recalled.

Even a few of the rabbis at one of the recent court hearings related to Bab al Yemen’s case said they remembered a few places like this in Jerusalem.

But since 2004, it has been rabbinate policy not to give kosher certification to restaurants outside of hotels that are open on Shabbat. This is due mainly to logistics, such as how a supervising rabbi would oversee a restaurant on Shabbat, when it is forbidden to work or travel, said Koby Alter, spokesman for Israel’s chief rabbinate. This concern is not valid for hotels, where a supervising rabbi can stay during Shabbat.

“And most hotels know before Shabbat how many guests will come to eat,” Alter said. “Restaurants cannot know, so there is a big fear that they may transgress Shabbat,” by cooking more food.

Having a restaurant open on Shabbat would also look like a transgression of Shabbat, unlike in a hotel where it is widely accepted that meals will be served on Shabbat, he said. “Opening a restaurant on Shabbat (in Israel) is not considered a necessity,” Alter said, the way that serving kosher-supervised food in a hotel, hospital or army base is. “The rabbinic council also sees a difference between restaurants abroad, where kosher food is needed, and restaurants in Israel, where kosher food can easily be found” in homes or purchased before Shabbat starts. He added that opening a restaurant on Shabbat would also encourage people to break the Sabbath by driving there.

So restaurants either get kosher certification and close on Shabbat, or they forgo the certification, even if they are following kosher dietary laws, because they want to stay open, which also means they lose most of the business of the religious public during the week.

“It’s often a dilemma,” Berman said.

But there are a few exceptions.

Dag al HaDan, a certified-kosher fish restaurant in the Galilee region, has an additional kitchen and dining area to cook and serve food on Shabbat. Because the areas are separate, and the kosher-certified kitchen and dining area are closed on Shabbat, it was able to keep its certification for the weekday section of the restaurant, still attracting religious customers Sunday through Friday.

“The rabbis helped us come up with this solution,” said Dag al HaDan’s marketing manager, Lea Gofer. “This way we get business on Saturday without losing business during the week from religious people because we do have a kashrut certificate for the rest of the week.”

In Jerusalem, Hadir Bar, a cafe in the Hansen House complex, which used to be a hospital for leprosy patients before it was turned into an exhibition and community events space, was open on Shabbat last summer with two menus: one with freshly cooked items, and one containing precooked dishes for those who keep Shabbat. It hopes to resume the model again this summer, when the place—where most seating is outdoors—is much busier than during the colder months, but staff said one challenge was knowing how much food to make ahead of time without experiencing a lot of waste. It does not have kosher certification but uses kosher ingredients. Another cafe on the same property, Ofaimme Farm, has a Tzohar certificate and is closed on Shabbat.

But one little-known and recently exposed example has given Vadai the most hope. He recently learned that in the departures terminal of Ben-Gurion airport, there is a McDonald’s open on Shabbat, serving pre-made food that customers pay for via credit cards on computer tablets rather than with cash, with rabbinate certification. This McDonald’s opened about two months ago, but before that, in the same location, a branch of the Israeli chain Burger Ranch also operated quietly on Shabbat with a kashrut certificate for more than 16 years, Alter said.

“This place is almost abroad,” Alter said, saying that was a main reason for allowing the arrangement. Only with the switchover to McDonald’s, which was reported in the local press, has the situation attracted public attention.

“I think this is really going to help our case,” said Luvitch, the lawyer working with Vadai. In addition to citing the practices of McDonald’s and hotels, Luvitch said the case will also focus on a legal mandate that says the rabbinate cannot consider factors other than dietary laws when granting kashrut certificates. So withholding them from places operated within the confines of religious law on Shabbat is illegal, Luvitch said. In the meantime, Bab al Yemen will continue opening for Shabbat customers, serving up hamim, jachnun, and various salads, even without the stamp of the rabbinate.

But, still, not everyone will go there.

“As an Orthodox rabbi who very much respects [Vadai] I would never advise anyone to eat there,” Leibowitz said, “Places really need supervision, and so far they don’t have it.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Sara Toth Stub is a Jerusalem-based American journalist who has written for The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones Newswires, Associated Press, and other publications.