Terminator Temptation

Power struggles, robot wars, and the difficulty of democracyNumbers 16:1–18:32

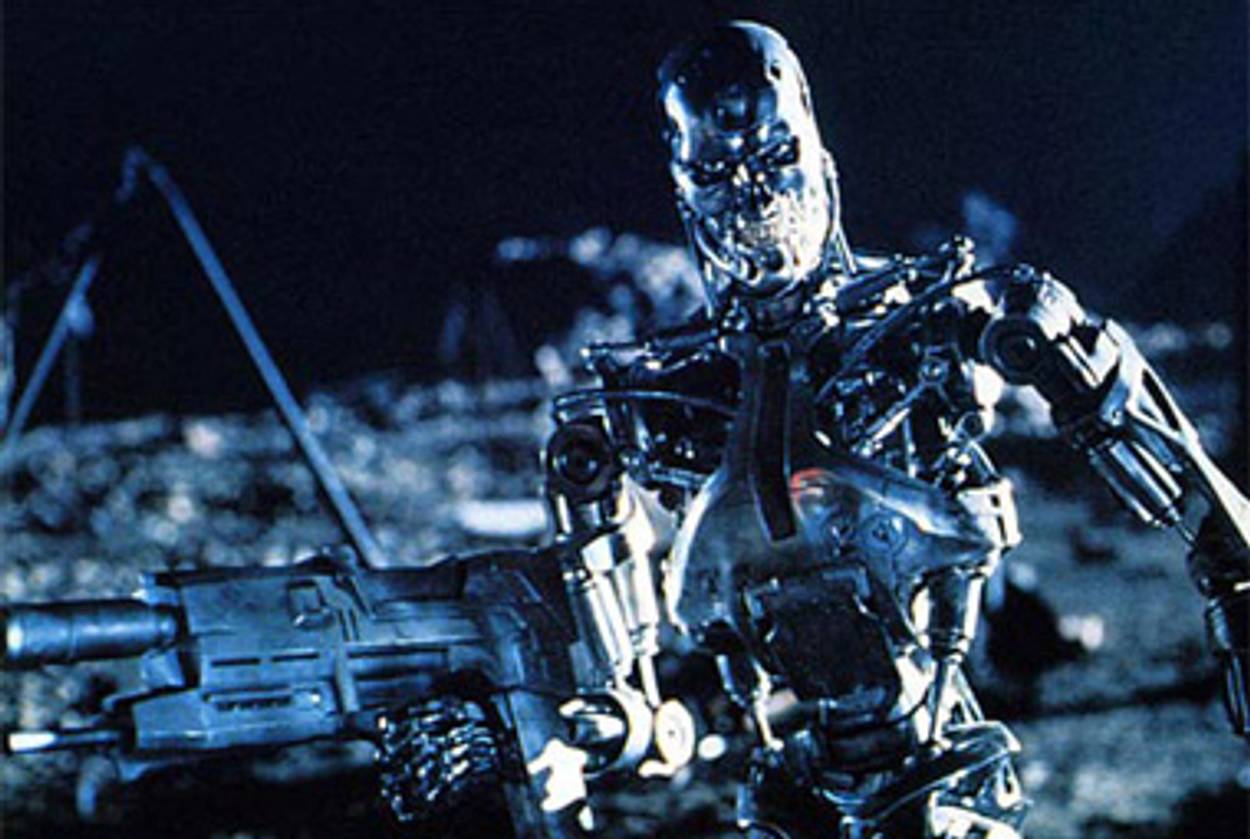

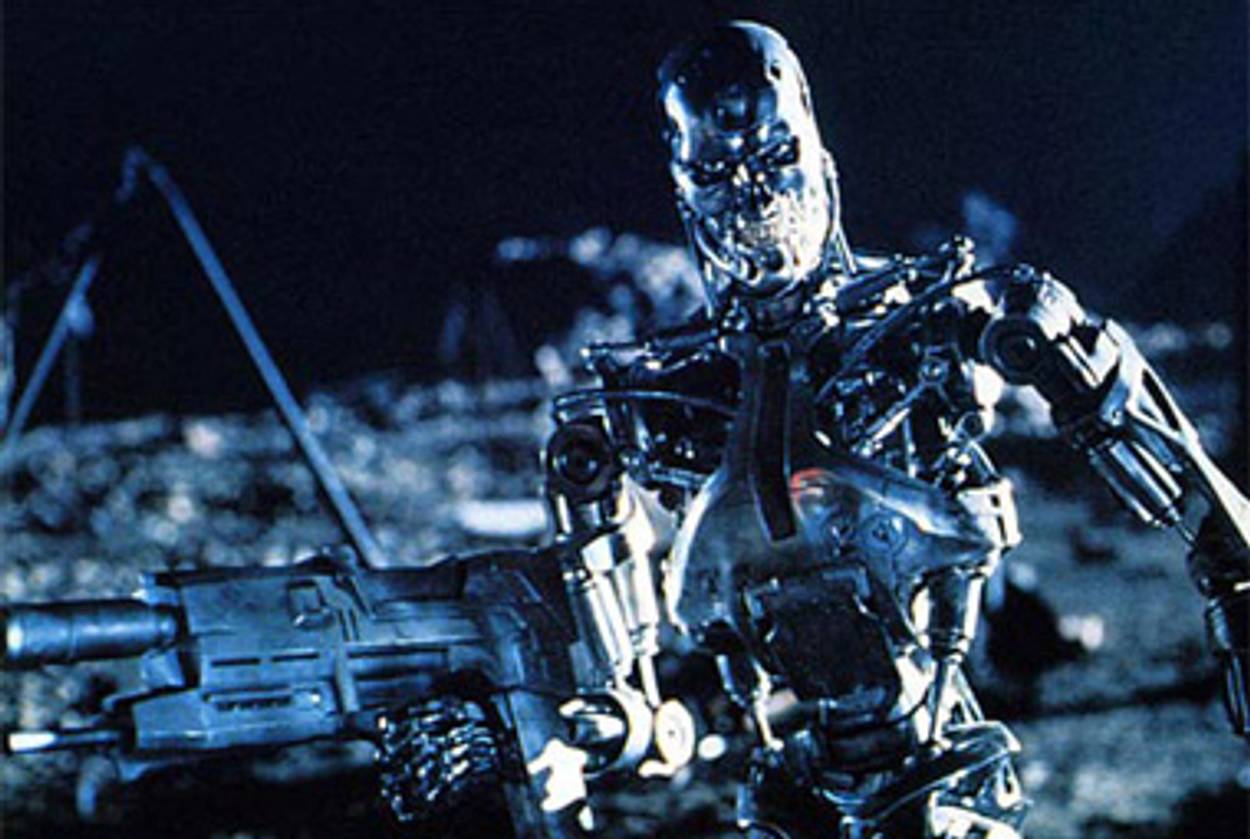

One of the many ridiculous moments in the thoroughly laughable new movie Terminator Salvation features a stand-off between the marvelous Michael Ironside as General Ashdown, the leader of humanity’s revolt against its futuristic robotic oppressors, and the dour Christian Bale as John Connor, a constipated-sounding commando who many trust is mankind’s sole savior. Believing he has discovered a loophole in the robot army’s defense system, the general orders an attack on its desert HQ, conveniently located—where else?—in southern California. For reasons too preposterous to repeat here—but that involve fathers, sons, and the most poorly conceived time-travel plot point since Ashton Kutcher’s The Butterfly Effect—Connor refuses to partake in the assault.

Watching Bale cough out his inane lines, the teenagers slouched a few rows in front of me cheered noisily. It made me shudder: not that I minded the distraction, quite the opposite, but I wondered why these adolescents were so quick to side not with Ashdown and his crew—an impressive and multiethnic cabal, looking a bit like what might have happened if those kids in the iconic Benetton ads had grown up, formed a militia, and devoted their lives to kicking robot butt—but with a lone lunatic possessing of a limited vocabulary and messianic aspirations.

I know, I know: it’s only a movie, and the audience, naturally, is primed to empathize with the hero. And yet, in a film that made so little sense, I thought, a normal person’s sympathies should have fallen with the seasoned and sensible general.

The same thought echoed through my mind a few days later, as I read this week’s parasha. It features no menacing cyborgs, no nuclear wastelands, and—Hallelujah!—no Christian Bale. But at its core, it presents the same moral dilemma those dudes sitting in front of me were so quick to resolve, namely, what is the nature of leadership and what gives one the moral authority to issue orders to one’s fellow men and women?

As the story begins, Moses, like a biblical Rodney Dangerfield, still can’t get respect. This time, however, it’s not just the cantankerous Israelites who call his authority into contest; it’s Korah, the grandson of Levi and a member of the elevated priestly class. And Moses, says this silver-tongued challenger, is keeping the people down.

“You take too much upon yourselves,” Korah and his cohorts reprimand Moses and his brother Aaron. “For the entire congregation are all holy, and the Lord is in their midst. So why do raise yourselves above the Lord’s assembly?”

Moses hears this, and falls flat on his face. Korah, he had to have realized, makes a valid point. After all, wasn’t it God himself who said the whole of Israel were a holy nation and a kingdom of priests? And why would such a blessed people succumb to the autocratic rule of one bearded guy?

Of course, Moses has little to worry about: God soon resolves this challenge, as God so often does, with some smiting. Moses’ leadership remains intact; but Korah’s argument rings on. After all, when we root for Moses aren’t we, like those boys in the movie theater, rooting for the wrong team? Isn’t Korah the General Ashdown of this story, logical and levelheaded, and Moses an ancient John Connor, a tortured soul who believes the fate of his followers rests entirely in his hands?

That may very well be the case. But this argument also ignores one crucial aspect: both General Ashdown and Korah were wrong.

In Terminator Salvation (caution: spoiler ahead!), Ashdown’s belief that he had found the machines’ Achilles heel proves to be a grave strategic error, nearly costing mankind its very existence. And Korah’s associates, Dathan and Abiram, believe that Moses messed things up by taking Israel out of Egypt, the real land of milk and honey, and leading them through an endless errand in the wilderness. In both cases, then, the wellbeing of the people is protected by a zealous vanguard that pursues its convictions with no regard for common sense, perceived notions, or popular sentiments.

That’s a hard thought to bear for us enlightened children of modernity, especially as we cheer for our fellow democrats in Iran who are trying to topple precisely such a zealous vanguard. Here we are, having hailed Moses and John Connor both, deriding another messianic man following his own crazy heart, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Why do we believe the rebelling prophet of the war against the machines when he claims that he must delay a major attack in order to save the man who would one day travel back in time and become his own father, but not the lunatic who claims that the recent elections solidify his status as the leader of the Islamic Republic? Why do we profess now one principle, now another?

Because we’re complex creatures, and unlike the biblical Israelites, the men and women of post-apocalyptic southern California, or those teenagers howling at the screen, we understand that leadership is a delicate and volatile thing, requiring at times subservience and at others obduracy.

This, perhaps, is what makes democracy, in the words of one famous leader, the worst system of government except for all of the others that have been tried. If only that man was around to lead the uprising against those pesky robots.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.