Enchantment

When he left the world of observance, a young San Franciscan took with him the trops for chanting Torah and applied them to the works of Walt Whitman

Recall a few of Walt Whitman’s most famous lines—“I celebrate myself, and sing myself”; “I sing the body electric”; “I hear America singing”—and you know that Whitman’s poetry all but begs to be sung. But call up a full stanza—“Do I contradict myself?/ Very well then I contradict myself,/ (I am large, I contain multitudes)”—and the difficulty of singing Whitman’s free verse, unrhymed and rhythmically unpredictable, should be clear as well.

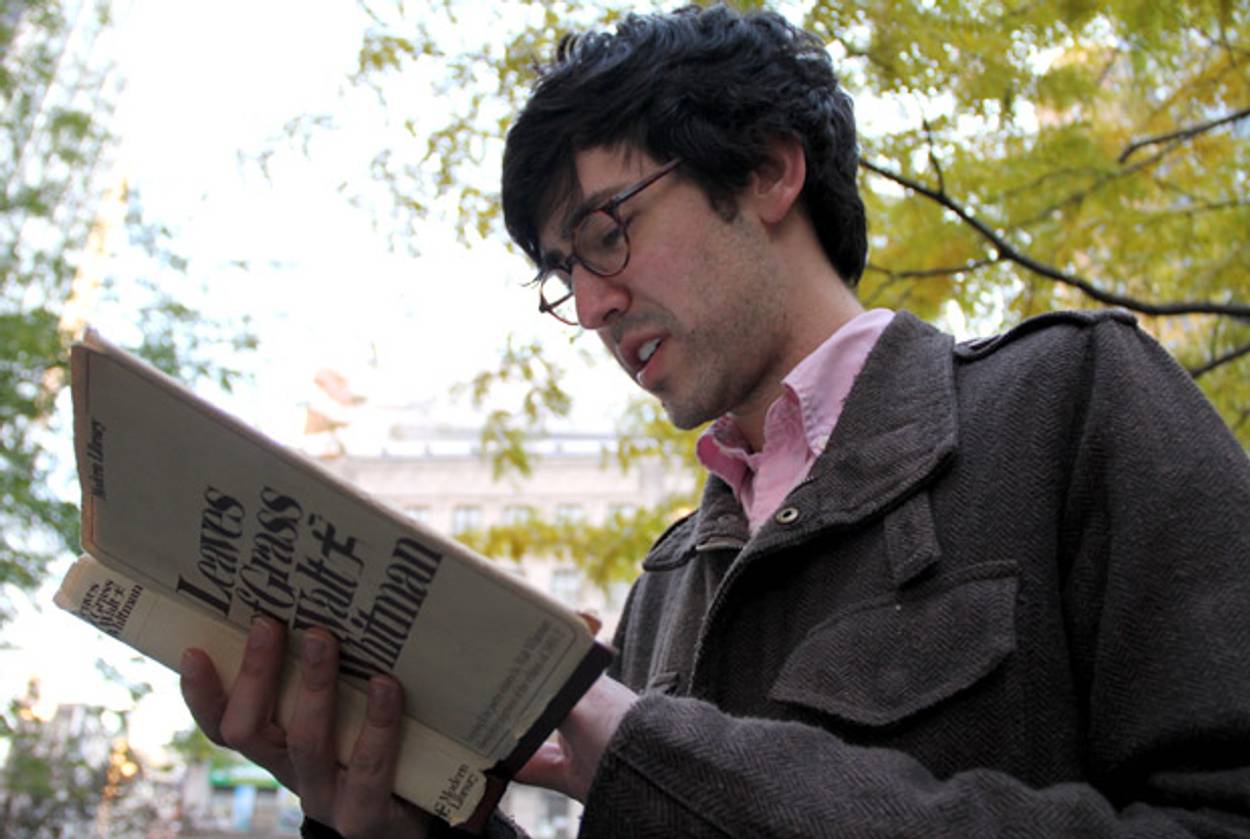

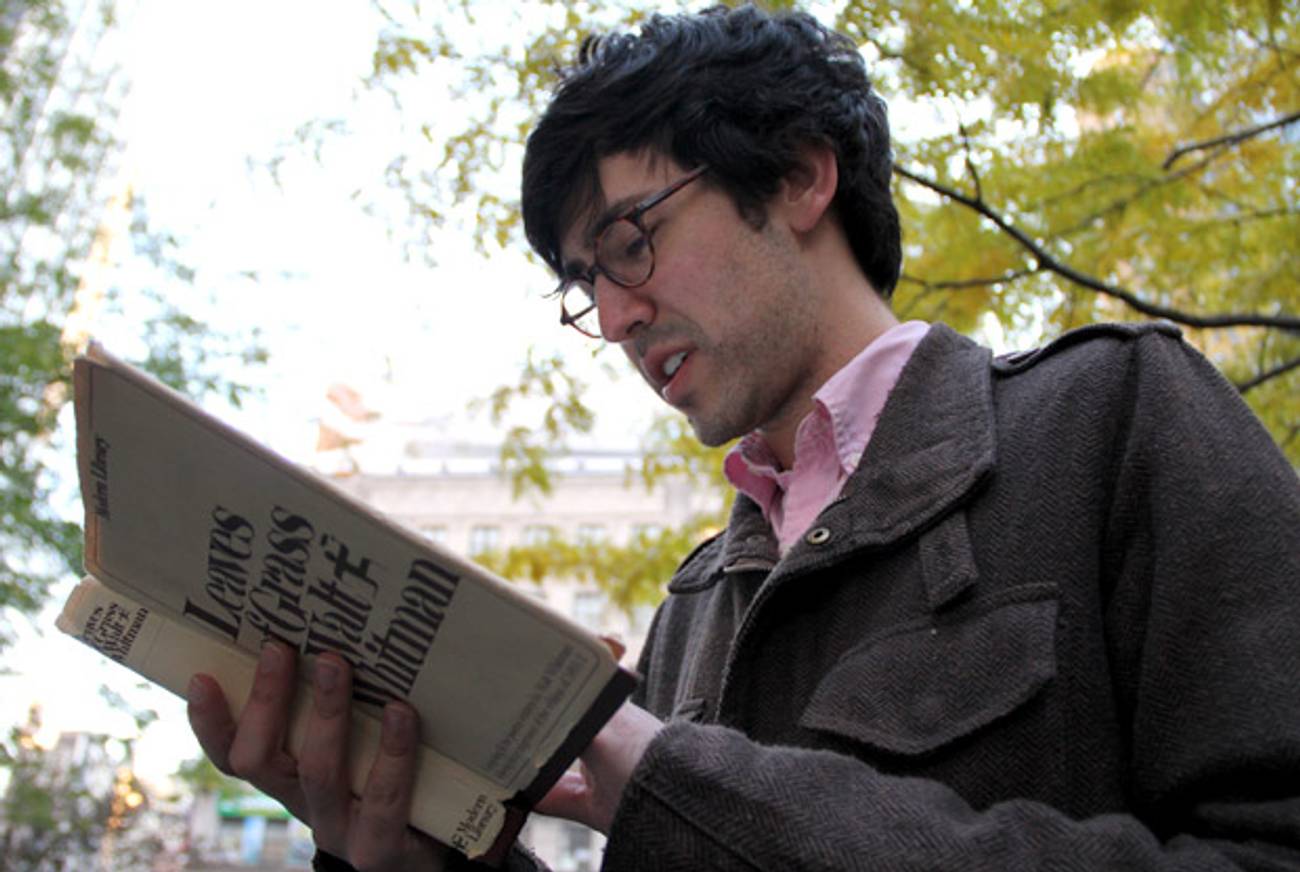

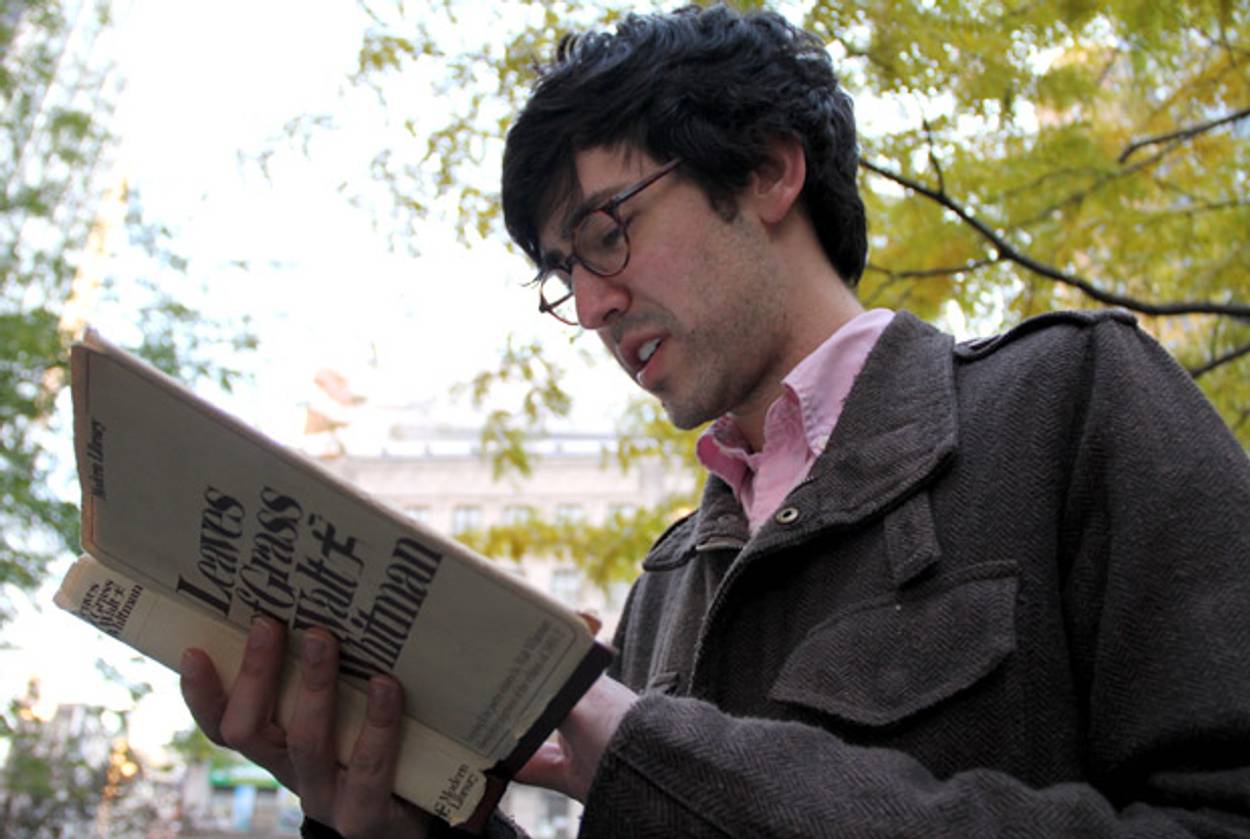

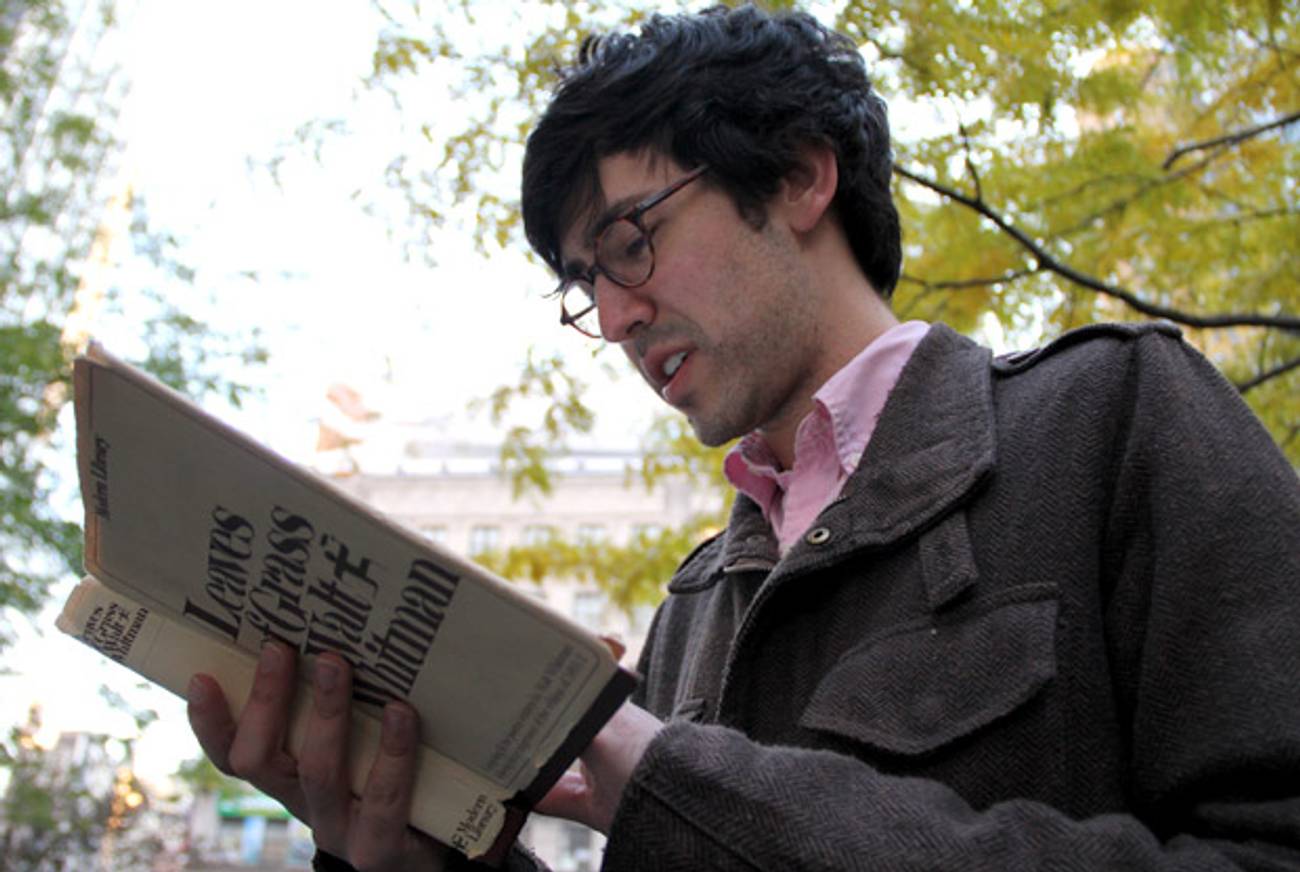

The coupled invitation and challenge presented by Whitman’s poems have attracted hundreds of composers, including Benjamin Britten, Kurt Weill, and Leonard Bernstein, who have set them to music. It proved irresistible, too, for Daniel Redman, now a 30-year-old civil rights attorney in San Francisco, when he fell in love with Leaves of Grass, Whitman’s magnum opus, six years ago. Redman had studied musical composition as a teenager, but his attempts to create art songs or choral arrangements around Whitman’s poems left him cold. What finally did feel right to Redman—and became the basis for a 40-minute-long vocal work—was setting Leaves of Grass to Torah-trop-inspired chant. (To watch a video of Redman performing, click here.)

When Redman first encountered Whitman during a winter break from law school at the University of California at Berkeley, he was recently out of the closet and transitioning away from a period of traditional religious observance that had lasted for several years in his young adulthood. Whitman’s celebration of both spiritual and bodily reverie, including love between men, resonated deeply with him in a musical language that Redman eventually came to associate with Jewish prayer.

“I realized that the musical experiences that had been most ecstatic for me had been in a Jewish context,” Redman told me. “But my kavanah”—the intense mindfulness that is supposed to accompany the performance of mitzvot like prayer—“had kind of died in a traditional davening context, and by setting these poems to music, I found a new avenue for that.”

Redman saw something powerful not just in the sounds but in the functional aspects of the trops created by medieval rabbis and still used today to chant Torah and other biblical texts. For one thing, trop, as Redman put it, “serves an exegetical function”: It creates a kind of punctuation that can guide readers through an unwieldy text like the Jewish scriptures or Leaves of Grass, which was published in six (or nine, depending on whom you ask) editions composed over nearly four decades.

Cantillation also acts as an aid to memorization—something especially vital, Redman pointed out, for a diasporic people seeking to transmit values and stories across generations. When you sing a text, “you just internalize it in a way you don’t otherwise,” he said. “It creates a portable tradition.” Redman seems bemused by the audacity of his own project and the questions it raises. Can a single text, particularly one by a dead white man, speak to a collective as diverse as the gay community? Does it matter if Whitman himself hoped to call such a community into existence through his work? Yet despite such questions, he dreams of creating a version of Leaves of Grass that could serve as a portable tradition for another people in diaspora: the gay community.

Redman is quick to note that by adding trops he is not trying to turn Whitman into holy writ. But Whitman, an avowed skeptic of organized religion, at one point referred to Leaves of Grass as a “Bible of the New Religion,” and many scholars have noted his literary debt to the Hebrew scriptures.

Redman’s project made perfect sense to Irwin Keller, the lay leader of Congregation Ner Shalom, a Bay Area Reconstructionist synagogue where Redman chanted Whitman at the end of Friday night services last March.

“It has heaven and it has body and it has suffering, all of these great themes that you get in Psalms, you get in Lamentations, you get in Song of the Sea,” Keller said of Leaves of Grass. These same texts of the Old Testament, he noted—“the ones that are really poetry as opposed to law”—are traditionally set off from more workaday parts of the scriptures by being chanted with their own special trops.

Setting the first two short poems in Leaves of Grass took three years, but then, Redman said, “I started to have a musical vocabulary I could work with.” He can now chant from memory the 24 poems that make up “Inscriptions,” the first book of Leaves of Grass, and several more chosen from the next book, Song of Myself, and from the intensely homoerotic Calamus poems. Over the past year, via word of mouth, Redman has been invited to chant Whitman at the San Francisco Public Library and for a small audience at the home of Esther Schor, a Princeton University professor of English, on her birthday.

When Redman performs, all self-consciousness about his project vanishes. He chants fortissimo, with mesmerizingly total commitment. It’s not a reading of Whitman, it’s “more like a channeling of Whitman,” said Schor, who has written on the poet and his contemporaries. “Everyone was completely dumbstruck by it.”

Rhythmically, Redman’s incantation bears the unmistakable sound of traditional leyning, or Torah chanting. Instead of being fit into a regular meter, each word in a phrase gets its own pattern of elongations and inflections. But its melodies are uncannily distinct from the trops that have been used to chant the Torah and other biblical texts since the medieval period. Different audiences hear different things. Keller heard something Appalachian. Schor detected the strains of Shaker shape-note singing.

And when Lawrence Kramer, a Fordham University English and music professor who has written on Whitman’s musical adaptations, listened to an audio clip of Redman for this article, he heard Whitman. In 1992, an English professor at a Texas community college discovered that the poet, already dead for a century, had left behind a 36-second phonograph recording of lines from his poem “America.” If the recording is authentic, as scholars believe it probably is, it uncannily resurrects the Brooklyn drawl of this poet who celebrated the sound of his own voice. Like Redman, Kramer said, Whitman elongates his vowels, giving his recitation a chant-like quality.

“He refers to his poetry as chant again and again; he suggests it should be musicalized,” Kramer said. “In a way, you can say that what Redman is doing is very much consistent with Whitman’s conception of how his verse should be orally delivered.”

Marissa Brostoff, a doctoral student in English at the CUNY Graduate Center, is a former staff writer at Tablet and the Forward.

Ari M. Brostoff is Culture Editor at Jewish Currents.