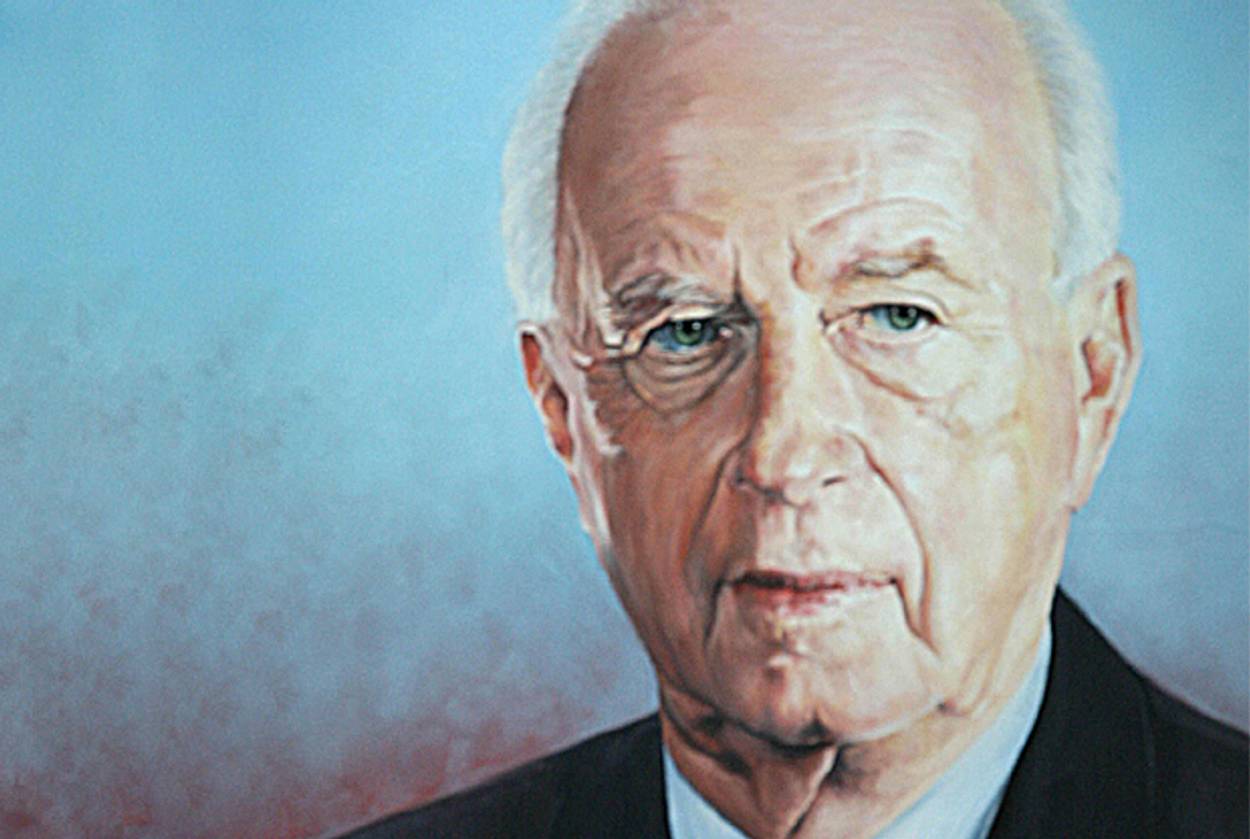

Grim Anniversary

Today would have been Yitzhak Rabin’s 90th birthday—as good a time as any to remember, and repent for, the time I considered assassinating him.

It was still Shabbat in St. Paul. I was staying at the home of Chabad friends, less than a block from the shul. We were in the middle of eating a late lunch when there was a knock on the door. A friend of mine, a fellow right-wing activist—not Orthodox—was standing there, pale as a ghost. “Rabin’s been shot. He’s dead. An Orthodox guy did it. I thought you should know.”

“Peres?” I asked. “Did he get Peres, too?”

My friend said the assassin hadn’t tried to shoot Peres. He had only tried to kill Rabin.

“That’s no good,” I said. “Peres is worse and now the whole country will back ‘peace.’ ”

My non-Orthodox friend believed the assassination was a bad thing, not because the assassin had failed to complete the job by killing Peres, but because it would lead to an inevitable crackdown on the political right and on Orthodox Jews.

“Well, at least he got one of them,” I said.

My host’s wife was horrified. A prime minister of Israel had been murdered. To her, this was nothing but a tragedy.

Her husband and I tried to set her straight. We reminded her that the Lubavticher Rebbe had viewed any concession to the Arabs—even giving them a small amount of territory—as an existential threat, an imminent danger to Jewish lives and a violation of Jewish law. To many of my fellow Lubavtichers who heard the news later that day in shul, Rabin’s death was not unexpected. He had, after all, disobeyed the leader of all Jews, Chabad’s Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who, more than a year after his death, was still for many the presumptive messiah.

The Rebbe’s position was clear to us. We had heard it many times in casual conversation, even from Chabad rabbis: Rabin was a rodef, a pursuer, a term used in Jewish law to define a Jew who is about to kill another Jew. Jewish law allows anyone who realizes the rodef’s threat is imminent to kill him. Rabin’s peace deals would kill many Jews. They were already killing Jews, just as the Rebbe predicted they would. Rabbi Avraham Hecht, a senior Chabad rabbi who was very close to the Rebbe and who served as the rabbi of a large Sephardic synagogue in Brooklyn, argued publicly that Rabin was a rodef. In June 1995, Hecht told the International Rabbinical Coalition for Israel that Rabin was “one who intentionally hands over [the] bodies [or] property … of the Jewish people to an alien people [and] is guilty of the sin for which the penalty is death. … If a man kills him, he has done a mitzvah.” (In the aftermath of the assassination in 1995, Hecht was banned from entering Israel for more than two years.)

So, Rabin was a rodef, and now he was no more. The only regret expressed that I remember hearing was that the assassination should have been carried out two years earlier, before the Oslo Accords were signed. As Avigdor Miller, a non-Hasidic ultra-Orthodox rabbi infamously said after John Lennon’s murder: “The bullet came too late.”

The notion that Rabin had been murdered two years too late meant something more to me than it did to others, because two years earlier, only days before the Oslo Accords were signed on the White House lawn, I was told by a rabbi to kill Rabin. And all things being equal, with all the years that I’d been part of this fundamentalist community and a committed follower of its leader, there was a chance I’d try do it.

***

It was late summer. An Iranian Jewish friend, a Lubavitcher Hasid, was hosting Rabbi Moshe Yehuda Blau, an elderly Chabad rabbi who made his living finding and republishing halakhic commentaries written by medieval rabbis. He was in town fundraising for his next project. Blau was well-regarded inside and outside Chabad, and he sat with several other elderly rabbis (sometimes including Avraham Hecht) in special seats near the Rebbe when the Rebbe gave public talks. My friend wanted to take Blau to visit a quadriplegic friend of ours in the hope that the rabbi would give our friend a blessing. He asked me to come along.

The three of us got in my friend’s van. As he started driving, my friend explained to Blau that I was very active in fighting Oslo and that I was about to make aliyah. Blau turned around to look at me carefully. He spoke softly but firmly: “Rabin is rodef and he must be stopped. If you can do it, you should kill him. But you have to do it in a way that you don’t get caught or that, if you do get caught, they don’t think you’re Orthodox. It’s a mitzvah to kill him. It must be done. The Rebbe is very strong about the dangers of land for ‘peace.’ But you must make sure you don’t get caught. And if you ever tell anyone I told you this, I’ll deny it. Do you understand?”

I nodded.

“Rabin must be stopped,” he continued. “Jewish lives depend on it.”

Blau turned back around to face the front. My friend continued to drive. After a few moments of silence, my friend asked the rabbi a question about the new book he was publishing. As they talked, I sat, silent, feeling as if I were being crushed by a giant weight that had just been unceremoniously dumped on my shoulders. That Rabin was a rodef in the eyes of halakhah was no surprise to me, and I didn’t disagree. But to be told that the moment I set foot in Israel, killing him would be my responsibility shocked me to my core. There are so many of us in Israel with combat experience, I remember thinking—couldn’t they do it? Why does it have to be me?

Two months later, I was living in Jerusalem and working for Chabad in the Old City. I often walked after work down Jaffa Road to the Ben Yehuda pedestrian mall where I’d eat dinner before taking the bus home. On these walks, I would find myself thinking about what Blau had asked me to do. It gnawed at me, and as much as I wanted to push it away and forget it, I couldn’t drive it out of my mind.

After awhile, I changed the route I took. After leaving the Old City, I veered southwest and walked past the U.S. Consulate to the Kings Hotel. From there I wandered through the side streets of Rehavia until I saw it: the prime minister’s residence. I was 100 feet from Yitzhak Rabin. Over the next few weeks I made that trip several times, each time making sure to pass by it quickly, as if I didn’t know or didn’t care what was there, as if I was late for an appointment somewhere nearby. No one stopped me or searched me. No security agents seemed to be watching me. I was just another Jew walking in Jerusalem, and Rabin’s security was focused on Arabs and hired terrorists from abroad. I could get close enough. With time I devised a way to do it that I thought had a decent chance of letting me getting away with it.

But I didn’t do it. Why? Because at the very moment I was first sure my plan could work, I thought of a relative who had been murdered. I saw his face clearly in my mind. And I thought of the pain his death had caused his immediate family and so many others. And the horror of death was clearer to me than it ever had been before, the finality of it, its awful permanence. I knew then that I could never take a life unless there was no other choice, unless it was absolutely and completely clear that it was kill or be killed.

I stopped walking by Rabin’s residence. I confined my opposition to political protest. And I went on with my life. But I still carried with me the burden of being instructed to kill the prime minister of the Jewish State. And as the demonization of Rabin continued around me, I wondered if I was wrong.

***

Long after Rabin was murdered, after years of soul-searching and leaving Chabad and then Orthodoxy, I came to understand what happened to me—and what probably happened to Rabin’s killer. Most of the people who hear incitement and hate speech will never go beyond parroting the hateful speech of their leaders, but a small minority will. However, most of the latter will lack something—opportunity, skill, courage, faith, or the conviction that there is absolutely no other way to achieve the necessary goal—and even though they plot, in the end they will not act.

But sometimes one or two of them will come to believe they have no other choice. They will overcome their own fears and doubts because they have seen that the others were unable to overcome their own. Or they will have no doubts or fears at all because they have become such true believers that they no longer have identities separate from their leaders. They will do what no one else can do, but what they know must be done. At that moment they become fully formed creations of those leaders, products of their indoctrination set loose by men who would never send their sons or grandsons to do that evil, and who would never do it themselves.

If he had lived, Rabin would have turned 90 today. When he died, he had in his pocket lyrics to the song “Shir Lashalom” (A Song For Peace). “He whose candle was snuffed out and was buried in the dust, a bitter cry won’t wake him, won’t bring him back.” The words were soaked with blood as if to prove the point. Oslo didn’t stop with Rabin’s murder. God didn’t send a redeemer to guide us. Nothing really changed, except that the earth got a little more of the blood that it always seems to crave, fed by yet another true believer who was absolutely certain that he was doing the will of God.

Shmarya Rosenberg publishes FailedMessiah.com. He has written for the Minneapolis StarTribune, Sh’ma, Moment, the Forward, Guilt and Pleasure, Heeb, Jewcy, and Tablet.

Shmarya Rosenberg publishes FailedMessiah.com. He has written for the Minneapolis StarTribune, Sh’ma, Moment, the Forward, Guilt and Pleasure, Heeb, Jewcy, and Tablet.