Home Away From Home

The Book of Esther, which chronicles the story of Purim, has special resonance for Jewish communities thriving in Diaspora

The Book of Esther seems out of place in the Bible, even to serious Bible scholars. Although it tells of near-tragedy, it is written melodramatically, almost as a farce; it is very hard to read with a straight face. The story and its style are altogether out of keeping with the other texts canonized as the Bible. In fact, the Book of Esther—which tells how Queen Esther saved the Persian Jews from a genocidal plot designed by an evil minister named Haman—doesn’t even mention God.

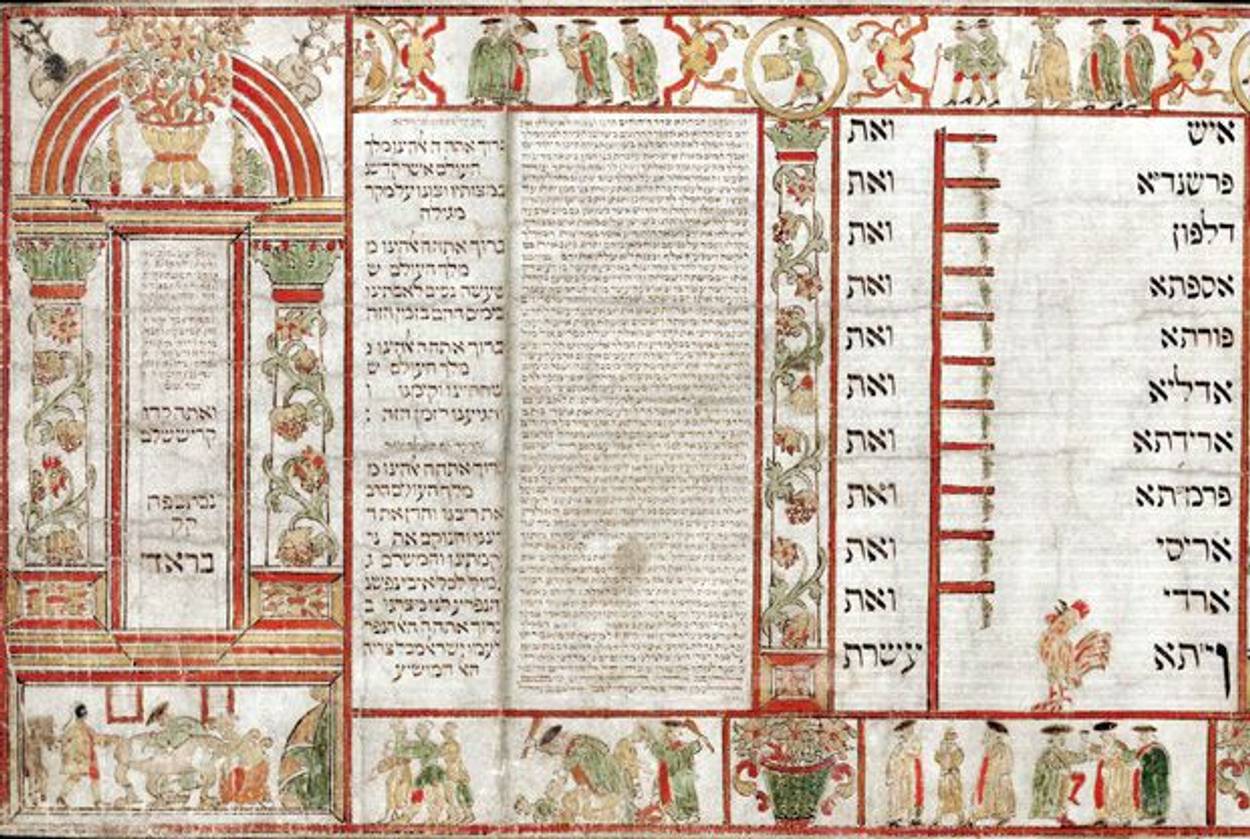

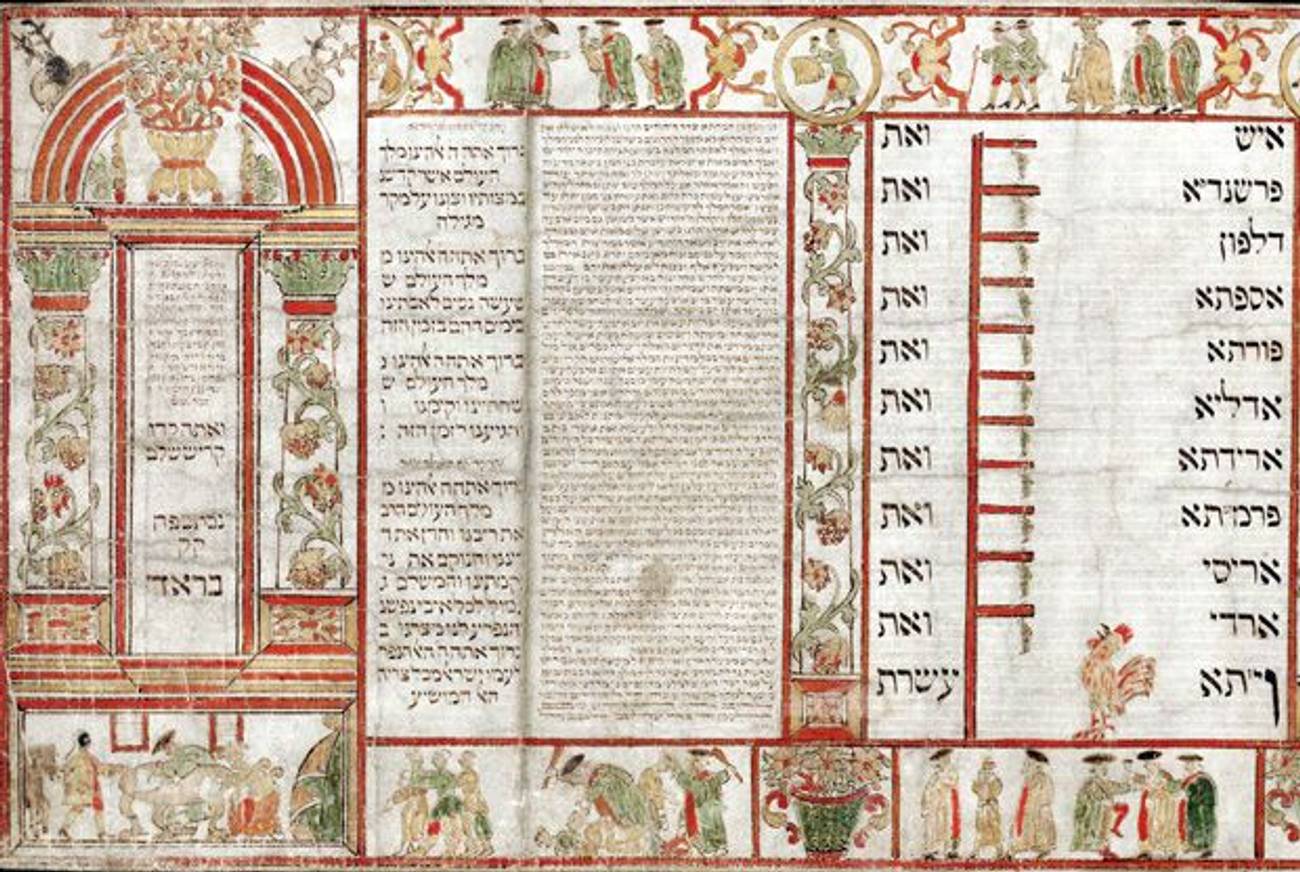

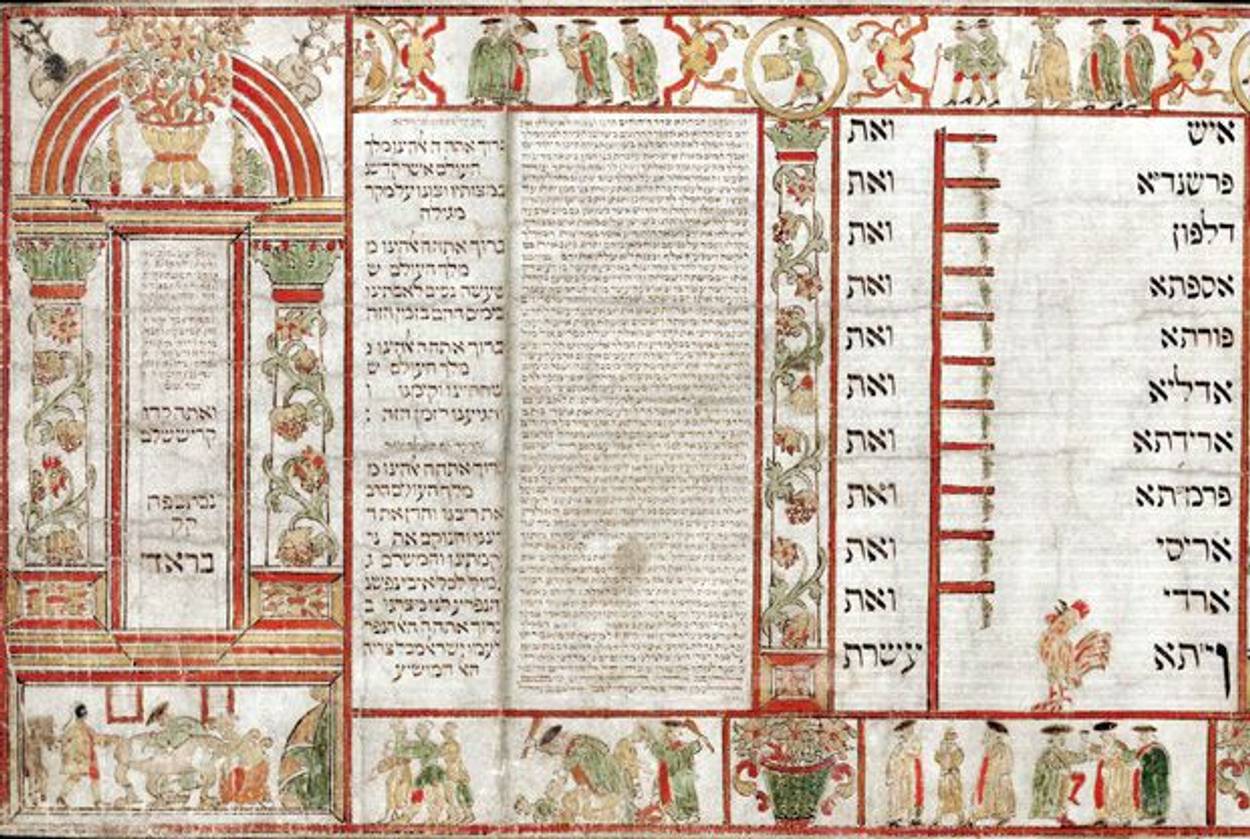

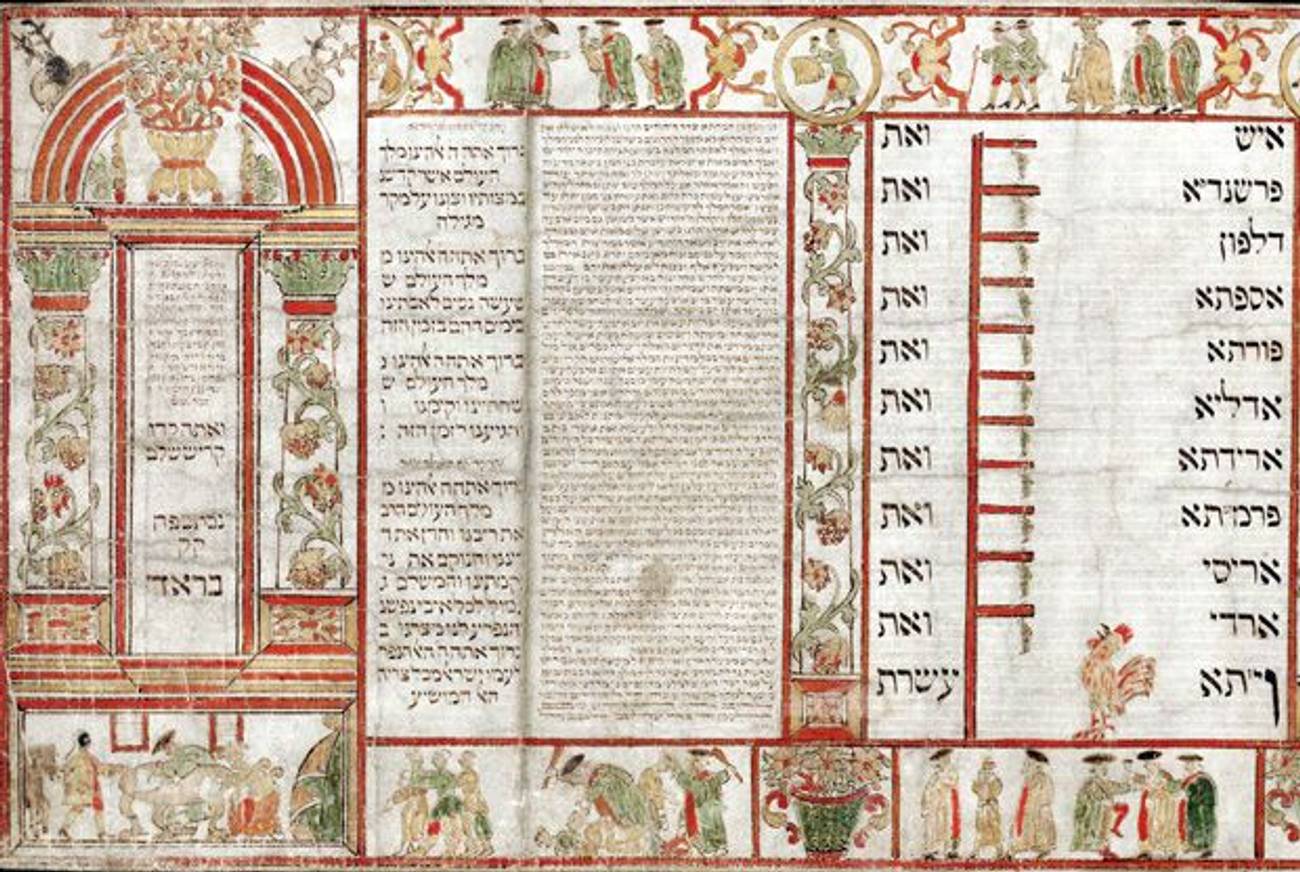

Yet despite its unique story and tone, the Book of Esther—also known as the Megillah, which is chanted aloud every Purim (this year, on the evening of March 7)—does have its place in the Bible. It forms part of a section of the scriptures known as the “Five Scrolls,” the other scrolls being the Book of Ruth, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, and Lamentations. There appears to be a common denominator to these short books: Each of them has a special interest in Diaspora. And the Book of Esther has a unique perspective on the subject.

Diasporas pose the dilemma of relating to an often-hostile “host” society and, at the same time, to the collective memory of a homeland. The Five Scrolls—separately and together—are an invitation to consider that delicate balance. They offer four broad responses: Return, Revenge, Takeover, and Remain. We call these Diaspora Dreams.

Return is the desire to go back to one’s homeland. The Torah is full of God’s warnings not to leave the Promised Land, and the liturgy is full of stories of yearning for return on the part of those who have left. Nowhere is the dream of Return more poignantly and explicitly illustrated than in the Book of Ruth: Naomi’s husband and her two sons die as punishment for having crossed into Moab to escape a famine in Canaan, while the bedraggled and bereaved Naomi and her loyal daughter-in-law Ruth are later rewarded for returning home. (Ruth, the Moabite, is to become the great-grandmother of King David.) Lamentations, too, focuses on Return, describing the glory of Jerusalem when it was populated by Judeans, then the ignominy of the city and the humiliation of its people when in exile; to “renew our days as of old,” the prescription in Lamentations is “return us Lord to thee”—not only spiritually, but geographically—a return to “the Mount of Zion which is wasted.” Return is the most obvious dream of those in Diaspora: to end the Diaspora itself.

Revenge is another recurring theme in the Five Scrolls, one whose target is not necessarily the host country but the marauder who forced the Jews from their homeland, or who fought unfair wars against them. In Lamentations, for example, the exiles in Babylon plead with God to strike at their oppressors: “do unto them as thou has done unto me … pursue them with passion, and destroy them.” Takeover is related to, but different from, Revenge in that its ultimate goal is to take over, or rule, the place where one finds oneself. The archetype of the Takeover dream can be found outside the Five Scrolls in Genesis, in the story of Joseph, who rises to a prominent position of power in Egypt.

It is not hard to guess why stories of Revenge and Takeover should appeal to Diaspora Jewish communities. They constitute a fantasy of deliverance without—or maybe with—the assistance of a miracle.

What is more surprising is that some stories about living in Diaspora are not about returning to the homeland, or fighting back against their oppressors, but about remaining in exile and making the most of that situation—the dream of Remain.

Song of Songs contains subtle allusions to the dream of Remain; the traditional reading of this scroll about the hide-and-seek love affair between God and the Jewish people suggests that staying put (rather than chasing each other) is the preferred course of action. Indeed, its thrice-uttered romantic dictate, “Do not awaken love until it so desires,” is interpreted by the midrash as a warning to postpone the dream of Return until the right moment; in other words, don’t pre-empt the Messiah. Ecclesiastes, too, can be read as containing an implicit message of “make the best of wherever you are” in verses like this: “Don’t say, ‘How was it that the former days were better than these.’ ”

But of all the scrolls, Esther is the most explicit illustration of the dream of Remain.

In fact, Esther contains elements of three of the four Diaspora Dreams. Haman is the focus of a Revenge fantasy, as he is ultimately hanged on the gallows he built for Persia’s Jews. And Takeover—in this case, the ascension of a Jewish queen, and the later appointment of Mordechai as deputy to the king—is also a key part of the story. But both of these are firmly based on Remain, a theme that permeates the Book of Esther and sets it in direct opposition to the Book of Ruth.

Mordechai and his beautiful ward Esther are seemingly well-off, living in exile in the Persian capital of Shushan. True, they are threatened by Haman, but they foil his genocidal plan and even rise in power in its wake. The Jews seem to continue thriving there afterward, leaving no hint of anything but the dream of Remain. There is no mention in the Book of Esther of the most obvious Diaspora dream, that of Return: There is no talk in Esther of fleeing, or going back to the Promised Land—only a concern with living safely in Persia. Living openly and freely as Jews in a foreign land is the dream, and in the Book of Esther, that dream is realized.

Living under the protection of a king, or other foreign ruler, has been a pattern of the Jewish Diaspora for centuries, and so the story of Esther has endured even as, over the years, a long list of tyrants has played the part of latter-day Hamans. Esther’s message is that Remain—staying put, but safely—is a worthy dream. The same can be said of Jewish Diaspora communities around the globe, which, while relishing the option of Return, often make the choice to Remain. And that, perhaps, is why the Book of Esther continues to resonate after so many centuries.

Elihu Katz is Professor of Communication at the University of Pennsylvania and Emeritus Professor of the Hebrew University of Jersusalem. Menahem Blondheim is head of the Communication Department at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.