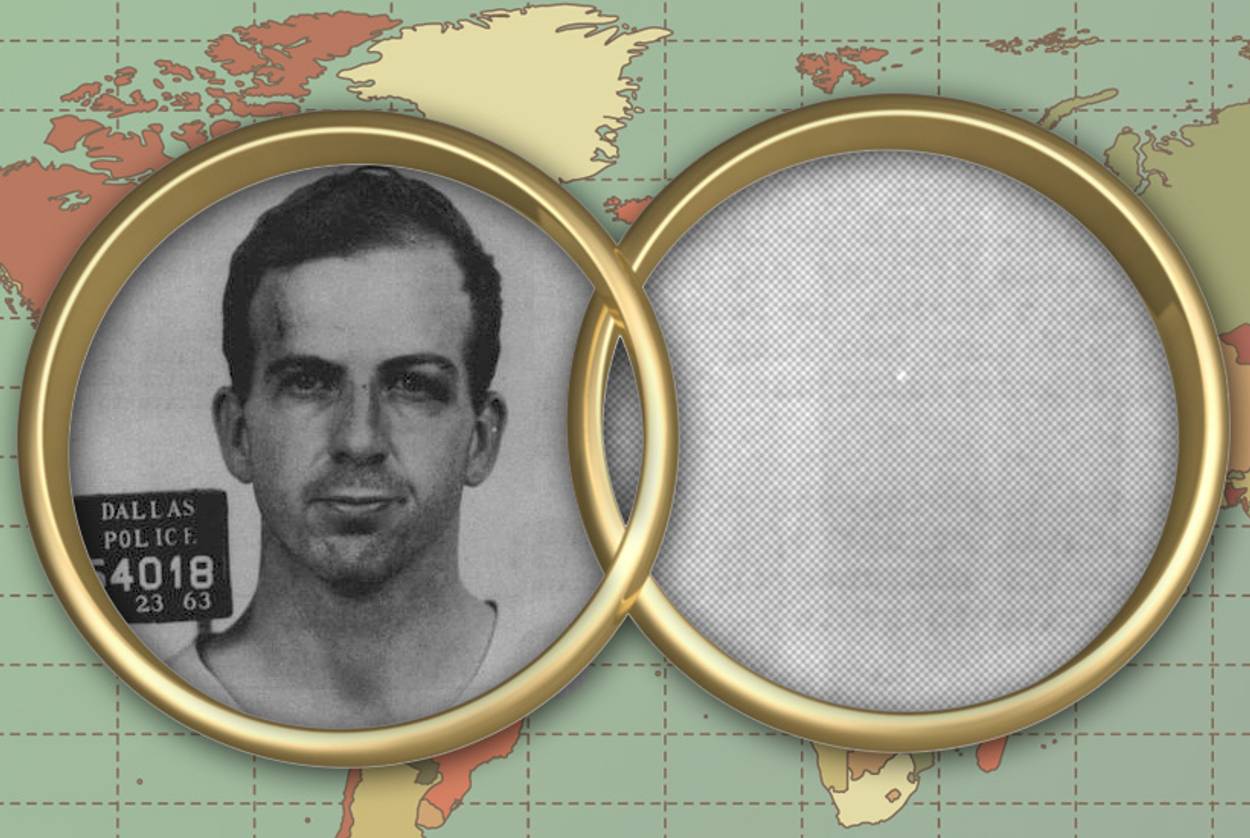

Could a Jewish Beauty Have Saved Kennedy by Marrying Lee Harvey Oswald in Minsk?

Ella German declined Oswald’s proposal, putting him on course to return to the U.S.—where he would assassinate the president

It was evening when Lee Harvey Oswald stepped off a train in Minsk on Jan. 7, 1960. The American did not know where he was, except that it was called Minsk. He had been in Russia for three months and believed he had defected to the Soviet Union. Just 20 years old, he was at the start of a long spiral that would eventually take him back to the United States and to a window in the Book Depository in Dallas, overlooking President Kennedy’s motorcade. But for now, Oswald was a young, rootless man in search of a place to call home, and this was where the Soviet authorities had sent him to find it.

Officially, there had been a city called Minsk since the 11th century, but the place Oswald found was really only 15 years old. The old Minsk had been flattened by the Germans after they invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. There had been a huge Jewish community in Minsk for centuries; before the war, it had included writers, artists, musicians, university professors, and party officials. In the center of the city, the Germans walled off a ghetto for the Jews, built a concentration camp called Masyukovshina, and killed, plundered, and destroyed wantonly. In the years immediately after the war, villagers from across the smoldering Belorussian plain streamed into what was left of the city. They rebuilt what had been an old, crammed, medieval tsarist trading center as a model communist city. The new Minsk was an unequivocal statement of the totalitarian impulse, stripped down and neatly fitted together, and without any history, energy, cultural edifices, or anything else that might feel busy, loud, urbane, or unexpected.

Oswald was given an apartment on Kalinina Ulitsa and a job at a factory making televisions, but it took him until April or May to make his first friend: a Jewish woman named Ella German. At that time, she was a montazhnitsa, or fitter, on the first floor of the Experimental Department of the television factory. Oswald fell for German almost immediately. In his diary he wrote: “Ella Germain—a silky, black haired Jewish beauty with fine dark eyes skin as white as snow a beautiful smile and good but unpredictable nature, her only fault was that at 24 she was still a virgin, and due entirely to her own desire. I met her when she came too work at our factory. I noticed her, and perhaps fell in love with her, the first minute I saw her.” Ella was the first woman he had fallen for—he probably felt more strongly about her than any other woman he ever met, including the woman he eventually married, Marina Prusakova—and it was his eventual break with her that would force him, more than anything else, to reassess his desire to make a life in the Soviet Union and return to the United States.

***

Soon Oswald and German were eating lunch together most days. “Alik could go at any time,” said German, who now lives in Akko, north of Haifa, in Israel. “He was not touched because he was American. He was in a special position, not like all of our workers. He could go earlier, so then I wouldn’t have to stand in line, and he could grab two lunches, for himself and me, and we would sit together.” German said that, from the moment she met Oswald, she thought he was curious, and she was keenly aware of the differences between them.“He was obviously very different from anyone I had ever met,” she said. When she spoke about him in our interviews, she didn’t sound as if she missed him; she was more detached. Oswald was an oddity, mostly because she had never expected to meet an American.

She had been born in Minsk in 1937, and like many other Soviet Jews, she stressed that she was “born into a Jewish family,” the same way that others said they were born into Russian, Ukrainian, or Armenian families. When the Germans came, in June 1941, Ella was with her grandparents in Mogilev, southeast of Minsk, while her mother was in Minsk. Her grandmother had come to Minsk two weeks before to take Ella, then 4, to Mogilev for the summer so her mother could take care of Ella’s brother, Vladimir, who was still a baby.

After the Germans occupied Minsk, no one knew where anyone else was. All they knew was that they had to go as far east as they could, so Ella and her grandmother and grandfather went to Tambov and then Saratov, and in Saratov, miraculously, they found her mother and Vladimir. But they couldn’t stop. As Ella put it, no one knew where Germany ended and Russia began. All they knew was that they had to keep going east. So they found a small space on a teplushka, which was a train for transporting horses and cows—teplo means “warm”—and that was how the family ended up in Mordovia, which is six or seven hours, by train, southeast of Moscow.

After Minsk was liberated in the summer of 1944, Ella’s mother returned alone from Mordovia and, after she found a place where the family could live, sent word that they should come. There was a swath of forest near their home that they called “the burnt place” because it was littered with rubble, and behind them, on a small rise, was the opera house. Everywhere smelled like tar. On Saturdays, when Ella was in high school, all the students would have a holiday, and they would clear debris (concrete blocks, rubble, shells, pieces of metal). This lasted until 1951 or 1952. By then, they had made enough room for the new buildings that started going up near the Svisloch, on Prospekt Stalina, Kalinina Ulitsa, Krasnaya Ulitsa, and elsewhere. A few years later, Ella became a montazhnitsa, and after that, she started working at the Experimental Department, where she met Oswald.

***

Even though Oswald had embraced the principles of communist revolution, he was, by the fall of 1960, beginning to wonder whether he belonged in the Soviet Union. Minsk only had so much to offer, and he had by then heard plenty of criticism of the regime. But Oswald was still in pursuit of Ella German. He was having other affairs, but Ella was more innocent and, therefore, more beguiling to him. She was also Jewish, which he made note of twice in his diary and, one suspects, found rather exotic.

German said she was unaware at first that Oswald had been seeing other women—she called them “girls”—but she found out later. This was when their relationship became more serious—at least, in Oswald’s eyes—in the late summer and fall of 1960. “Probably, like a man, he needed that,” German said. “I just learned about this at the end of October, at this party, and we spoke about it often, and there were several quarrels about it, of course. I was aggravated that he didn’t tell me the truth. I was offended. Right after that, I started not to trust him so much.”

On January 1, 1961, Oswald wrote: “New Years I spend at home of Ella Germain. I think I’m in love with her. She has refused my more dishonourable advanis, we drink and eat in the presence of her family in a very hospitable atmosphere. Later I go home drunk and happy. Passing the river homewards, I decide to propose to Ella.” Oswald appears to be serious here. He comes across, in his diary, as a little impulsive or, perhaps, taken with himself, but he had known Ella for several months, and it was not uncommon for people at that time to marry in their early twenties.

German had not been expecting Oswald on New Year’s Eve. They had made plans to spend the holiday together, but then they had quarreled. At a little past eight in the evening, he turned up at her house with a box of chocolates with a ceramic figurine on top. German asked her mother if he could spend New Year’s Eve with them, and her mother said, “Of course.” Everyone was there: Ella’s mother, her grandmother, her uncles (Boris, Ilya, and Alexander) and each of their wives (Lida, Shura, and Luyba). German’s mother sang and played guitar, and everyone danced. Two of her uncles were in the navy, and they had learned to dance the chechetka, the folk dance that involves tap-dancing while maintaining a perfectly erect back. “Alik liked it very much,” German recalled. “He drank heavily that night, and for the first time ever I saw him drunk.” Her mother served meat cutlets with potatoes, cabbage salad, and carrots with sour cream.

The day after New Year’s, Oswald saw Ella again. In his diary Oswald wrote: “After a pleasent hand-in-hand walk to the local cinima we come home, standing on the door step I propose’s She hesitates than refuses, my love is real but she has none for me. Her reason besides lack of love: I am american and someday might be arrested simply because of that example Polish Intervention in the 20’s. led to arrest of all people in the Soviet Union of polish origen ‘You understand the world situation there is too much against you and you don’t even know it’ I am stunned she snickers at my awkarnes in turning to go (I am too stunned too think!).”

German’s fretting about a “Polish Intervention” feels forced, to say the least. Viewed in this way, the end of their relationship, like the U-2 incident and the election of a young American president, was a function of global forces, not personal ones. But the truth is, she did not love him. When I met her, Ella said that, above all, she was surprised and bewildered by Oswald’s proposal. She didn’t know why he cared about her so deeply. Oswald seemed to grasp this. As he put it in his diary: “I realize she was never serious with me but only exploited my being an american, in order to get the envy of the other girls who consider me different from the Russian boys. I am misarable!” By the next day, his anger had subsided, but his unhappiness had acquired a more hopeless undertone. In his diary he wrote: “I am misarable about Ella. I love her but what can I do? it is the state of fear which was always in the Soviet Union.”

Oswald had closed out 1960 holding on to some of his early affection for Russia, and, in fact, New Year’s Eve at Ella German’s house had left him with a warm and romantic feeling, not only for German but also for Russia. It’s true that he had grown weary of the Soviet Union and daily life in Minsk, but he had not determined just yet that it was time to go. By asking for German’s hand, Oswald was signaling his willingness to stay. But she had said no, and almost immediately after that, all the doubts and angers that had been coalescing inside his head for the past several months sharpened into a desire to leave.

***

Before he could make a move, Oswald met Marina Prusakova at a party at the Palace of Trade Unions. She soon became a fixture in his life, and in late April they married. On May 1, he wrote in his diary: “Found us thinking about our future. In spite of fact I married Marina to hurt Ella I found myself in love with Marina.” Then, in the entry marked simply “May,” Oswald wrote: “The trasistion of changing full love from Ella to Marina was very painfull esp. as I saw Ella almost every day at the factory but as the days & weeks went by I adjusted more and more my wife mentaly. I still ardent told my wife of my desire to return to U.S. She is maddly in love with me from the very start.” He had found himself a wife, and she, an American, but their love, as it were, had a tenuous feel to it. Ella German remained lodged in his head—a wistful memory of the life he might have had in Minsk.

A year later, in May 1962, Oswald and Marina, along with their infant daughter June, left for New Jersey. One week before Oswald left Minsk, he approached German at the Experimental Department. They had not spoken for almost a year, and she was surprised when he came up to her at the end of her shift and told her he had something important to say. She said they could speak at the factory, but he said it was important. He wanted to go somewhere private. She said no. It would look bad. She added that she was married now. “He asked me if he knew the man I had married, and I nodded, and very abruptly, without saying anything, he just turned around and left,” German said in an interview.

German was always ambivalent about Oswald. She said she had never talked to the KGB about him because she cared for him. In fact, if she could have done it over, she said, she would probably have married Oswald. It was a matter of timing. In January 1961, when Oswald proposed to her, she was still not sure about him, and she didn’t feel as if she had to get married immediately. By the spring of 1962, her sense of urgency was greater. She said she was tired of not having anything to do on the weekends and going to dances alone, and she wanted a family. If Oswald had proposed to her in April 1962, she might have said yes. Still, she never disliked him, and later she sometimes wondered what their life would have been like together.

From the moment he returned to the United States, Oswald was in a state of constant motion, but really, he had been in a state of motion, fleeing, interloping since infancy. Now he had arrived at a point of homicidal and suicidal destruction. Did he plan to kill the president—Kennedy—months or even years before he did? No. But his angers and disappointments put him at odds with America, and he would have been open to the idea of killing an American head of state. He would not have been inhibited. The assassination would elevate him to world-historical status, and it would end all his pains and furies.

Adapted from The Interloper: Lee Harvey Oswald Inside the Soviet Union by Peter Savodnik. Available from Basic Books, a member of The Perseus Book Group. Copyright © 2013.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Peter Savodnik has written for The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Harper’s, and GQ. He is the founder of Stateless Media.

Peter Savodnik is the author of The Interloper: Lee Harvey Oswald Inside the Soviet Union. He writes for Vanity Fair, among other publications. He can be found on Twitter @petersavodnik.