The 1948 war began after the UNO declaration in favor of the establishment of a Jewish state alongside an Arab state and after the Arabs rejected the proposal. By the time the state was declared in 1948, most of the hard battles in the War of Independence had already been fought and some three thousand youngsters had already been killed. We all volunteered. Among six hundred thousand Jews, the percentage of casualties was indeed very high. And on the fifteenth of May we were wearily asleep after some battle or other when someone came and said Ben Gurion had established a state and we asked where and the man said Tel Aviv and we answered we’re Jerusalem and we haven’t established any state, and we went back to sleep.

Two days later, three of my friends were killed in a battle. That evening we dropped them into the pits we had dug earlier and I was left on my own. I waited on the lawn and someone who was killed a day afterwards came and picked me up in Ahi’s armored car and said we had to take Abba Eban back to Tel Aviv. The siege was on. Jerusalem was cut off. The ride was long and bumpy. We came across an Arab donkey that brayed at us and Haimke Keresh brayed back at him and shouted that’s regards from our donkey in my village.

So far, there was hardly any talk about establishing a state. From the 1940s, the Jewish struggle was mostly about free immigration. Had the British granted a hundred thousand certificates to Holocaust survivors who were waiting to come, maybe the state would have arisen years later. During the big anti-British demonstrations in the 1940s nobody, apart from a few, spoke about a Hebrew state. Most were struggling to rescue Jews.

It was early morning when we reached Tel Aviv in the armored car. A siren sounded. People could be seen dashing to the shelters. We got out of the armored car and stood stretching ourselves, because we had been on the road crowded together for eight hours. I was almost eighteen, I had already seen a lot of death, I had seen cruelty and vengefulness and dreadful poverty. The Tel Aviv streets were empty. I looked at the houses so planted in Tel Aviv, in the streets I knew, and I envied the people who had a Jewish state already but were nowhere to be seen because of the bombing. I arrived at my parents’ apartment and my mother says that when I came in I didn’t say a word and rushed to my room. I didn’t eat. Didn’t drink. Didn’t go to the lavatory. After all, I had just come from hunger and thirst. I stayed alone locked in my room wildly drawing on the walls with colored chalk I found in the drawer of my table. My mother says I climbed onto the table to draw on the ceiling, too. I didn’t let anybody in, I went out to the balcony and gaped at my sea, which was already part of the Jewish state; the sea from whence would come the Jews for whom I had enlisted at the age of seventeen and a half. I gazed at their sea that was still more mine, more home than any other home I remembered, at its deep evening beauty, and the sight of the sun striking the sea instilled confidence in me. I do remember a smell of burnt sausage. Apparently I went out for a moment and swallowed it in the kitchen. I remember the paraffin stove with an orphaned pot of food waiting for me. After a night and half a day I ran from our apartment in Ben Yehuda Street to the armored car and the guys were asleep, standing up. A fat man gave me a cigarette, but he didn’t speak because he didn’t know any Hebrew. On the ride back to Jerusalem, they began to shoot at us and two bullets came through the small slits through which we were shooting. Two of the men in the armored car were already lying dead at our feet. It was narrow inside and bullets were flying from one side to the other and I heard the shriek of the bullets and saw them exploding on the walls of the armored car and the two corpses at our feet emitted the smell of death, but the saliva still flowed from them.

Look, not everybody is capable of establishing a new state in a hostile environment after two thousand years. We weren’t given the tools for building the state. We had no teachers. We had rhetorical prophets who wanted us to bring salvation and we had bewildered parents whose families had perished in the Holocaust and who sent us to be fighters in the new Masada. We had short old revolutionaries who rallied behind us shouting in the belief that when Jews shout they are more in the right and they became increasingly rhetorical, dangerous and noble, for the moment seeing us as belonging to the chronicles of Israel, a nation now seeking to live in its own house, avenging the history of Israel, avenging pogroms we didn’t know because we were born here. We knew battles with Arabs, but no pogroms.

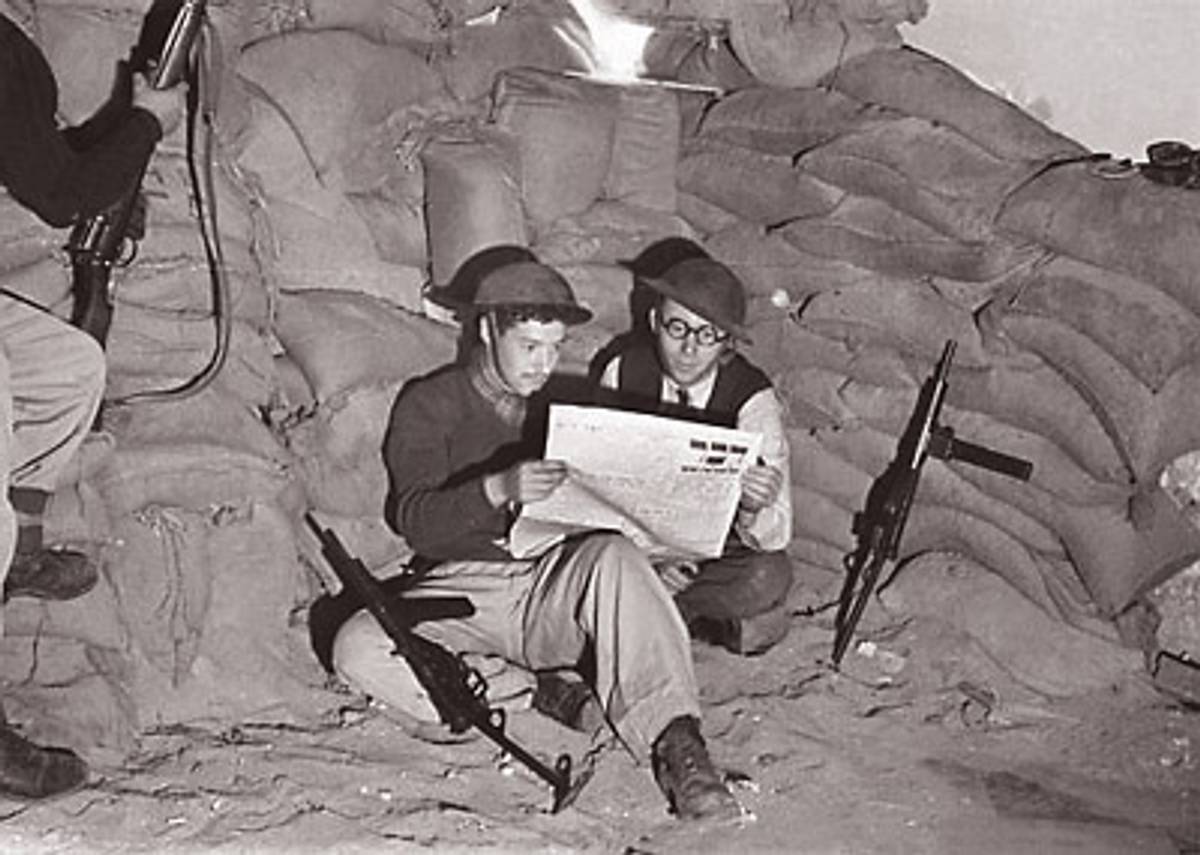

It was given to us to restore the respect of a humiliated People who were attacked in order to be destroyed, whereas we set out to establish the state against the Nazis more than to counter the Arabs who thought Auschwitz was sort of a city overseas. We were children of the bible with a homeland. A history. Poetry. We had in us the pain of Jews who allowed longing to change into prayer. Our parents came to renew our days as of old and sixty years ago, from December 1947 till the end of 1948, four hundred of my brigade that numbered twelve hundred youngsters commanded by Yitzhak Rabin, were killed in three months. It was a kind of Children’s Crusade. We were almost devoid of weapons, with officers who were talented but lacking in battle experience. We were few, alone, hungry, thirsty. We were in Jerusalem and on the way there and we had killed and been killed and we sang, “If we die, bury us in the hills of Bab El Wad,” we sneaked in from all sorts of places, we didn’t have a penny to our names and we sang how we would die. Longingly, firm in spirit, we sang a song with the words “we walk as if dead” and thought that it would be wonderful to die. Wise we were not. The wise don’t choose to go out and die at the age of seventeen without first knowing how to shoot. The wise prefer existing states rather than new states to be established among white rocks under a flaming sun. You had to be stupid, young, and crazy to fight the Jewish People’s suicidal war. To die for someone you don’t know and to discover only after the war that we had established the state for Holocaust refugees in camps somewhere in Europe.

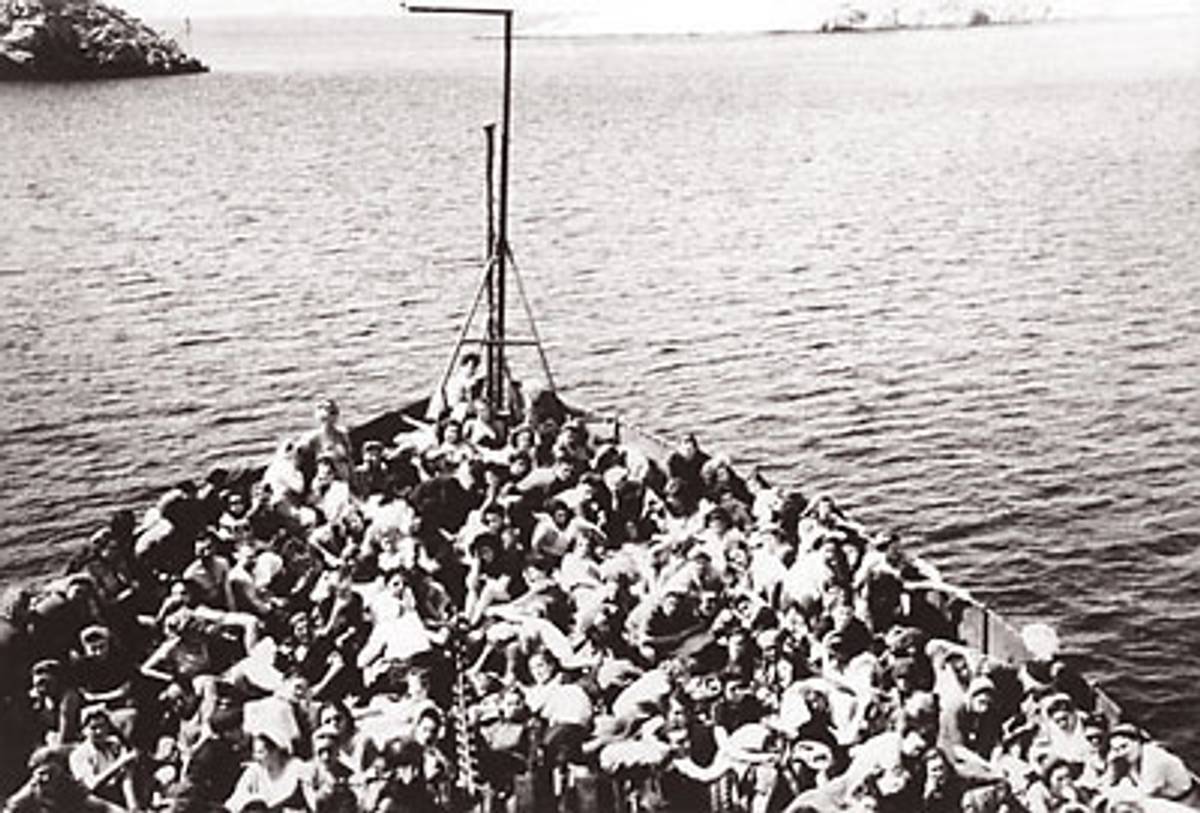

When we were still children, in the 1930s, the Arabs started an uprising against the British in order the block the flow of Jews into the country and they won. The English preferred the oil, gave in and closed the gates of the country. A German soldier on a submarine, seeing the sinking of illegal boats on the way to Eretz Yisrael, laughed and said, “The Jews are swimming to Palestina.”

During Hanukkah 1947, we hiked to Masada. It was quiet, with a lowering black sky, the heavenly hosts in abundance. We declared loudly enough to be overheard in Great Britain, “We will not forget thee, O Diaspora,” and a Palmach fellow who was with us drew his revolver and fired a symbolic shot against the enemies of Israel. After this I went for a walk. It was cold the way a desert knows how to be at night. Illegal immigration had just come to an end, the big war had ended two years earlier. I gazed at the lights of Hebron and Bethlehem and Jerusalem and thought that it was like Christmas in the movies and I heard a stone fall into the abyss and stumbled, luckily I was flexible and quickly swung backwards, realizing that I was standing on the edge of the mountain. I understood that had I taken one more step, I would have become a stone at the foot of the mountain.

Fascinated and alarmed, my legs shaking from what had just happened to me, I looked at the extensive lights of the Arab cities and Jerusalem and thought that if a Jew stands on the finish line he always sees Paradise and this is dangerous but beautiful. Then the Palmach fellow was wounded by a shot he fired by mistake and one of the guides ran tens of kilometers to Kibbutz Beit Ha’arava to get bandages while we pressed the shot fellow’s wound to stop the flow of blood and about five hours later his friend came back with a medic, near the River Jordan, after which we hiked for two days and went for a covert swim in the Dead Sea on our backs with our knapsacks on our stomachs, after all, we couldn’t sink but we burned from the salt water and the proud hills of Moab spread above us and dark stone crags loomed behind us in the night and a bat was there and the eagle crossed the sky and I thought about the concept of the finish line, not understanding exactly what this terrible expression meant, if standing on it you saw Paradise, but also the opposite.

A few months later, I had already volunteered in the war. After the battles, we would bring the bodies, lay them out and take some of their clothes to wear. We went out by night. Saw our friends hacked to pieces, the penis stuck in their mouths and we fought. They were pitiless. We were pitiless, too. Then I was wounded and almost died and I escaped from the hospital in Jaffa and went to Ramleh to organize a new brigade of jeeps. The town was empty. The Arabs had been chased out. Food still squatting on the tables. We slept in a beautiful house. It was awful and quiet and saddening. Suddenly, halfway through the night we heard a terrible noise. We went outside. A thousand, maybe more, people arrived in trucks. They cut the barbed wire fences enclosing the town and flowed past the evicted Arabs standing by the fence and crying that they wanted to return. These peculiar Jews who resembled a herd of animals darting from the trucks with the look of hungering wolves had never heard of Ramleh, but the instant they entered the houses, to sleep on sheets again for the first time in years and after all those camps, even though they couldn’t pronounce the name of the town they became its landlords. They were full of profound animosity towards the world, a tribe of jackals come down from the black mountains; people who emerged from hell to rejoin the history that now lay on the barbed wire, stricken and wailing in Arabic. The sight of the Jews grabbing every house was sad, but also imbued with a kind of magic, a human beauty beyond judgment. The last time any of them had a house or apartment was in the thirties. I remember having a pointed conversation in flowery Hebrew with a man who said that morality and justice are for celebrations, not life, and that we, unlike the Arabs, do not have relatives within ten kilometers.

Those Jews were stronger than we Israelis. Compared to them, we were jokes walking around inflated with self-importance because we won some Mickey Mouse war.

For them, war was Wehrmacht, Nazis, Gestapo, tanks, freight trains, grey huts, smoke, walking to God via the furnaces. They felt that they were wretched souls, winners only because they were alive. They dismantled the barbed wire fences the way children open bars of chocolate. They took. They stayed.

This strange encounter between the pleading Arabs at the fences and the beaten Jews falling upon a whole town that yielded sheets and refrigerators with food inside, was nothing compared to the unsolvable tragedy of our war that began eighty years ago and continued until the War of Independence and until today, under various names. Once, on a walk with my mother who grew up in Eretz Yisrael from 1909 and saw all possible bereavements, we came to Tel Aviv’s old cemetery and stood beside the common grave of those who perished in the Arab uprising in 1921 that was the beginning of the above- mentioned war. She was a girl then, and bandaged twenty-three Jews murdered near Tel Aviv. It was impossible to identify them because they had been disfigured and my mother standing beside that common grave said to me, Yoram, look what an inheritance I’m leaving you, my son.