‘Kristallnacht’: The Legal Status of the Bystander

Germans stood by as Jewish businesses and synagogues were burned, tens of thousands of Jews were arrested, and nearly a hundred were killed. Shouldn’t doing nothing about it be criminal?

I am child of the Holocaust. Both of my parents are Holocaust survivors. This essay seeks to answer three questions essential to my understanding of the Holocaust, the bystander, and my understanding of duty owed to another individual.

Those questions are: What do we learn from the Holocaust in general, in particular from Kristallnacht, regarding the bystander? What is the responsibility of the individual in the face of unmitigated racism and hatred? What is the most appropriate application of the painful lessons that can be learned from the tragic events of Nov. 9-10, 1938?

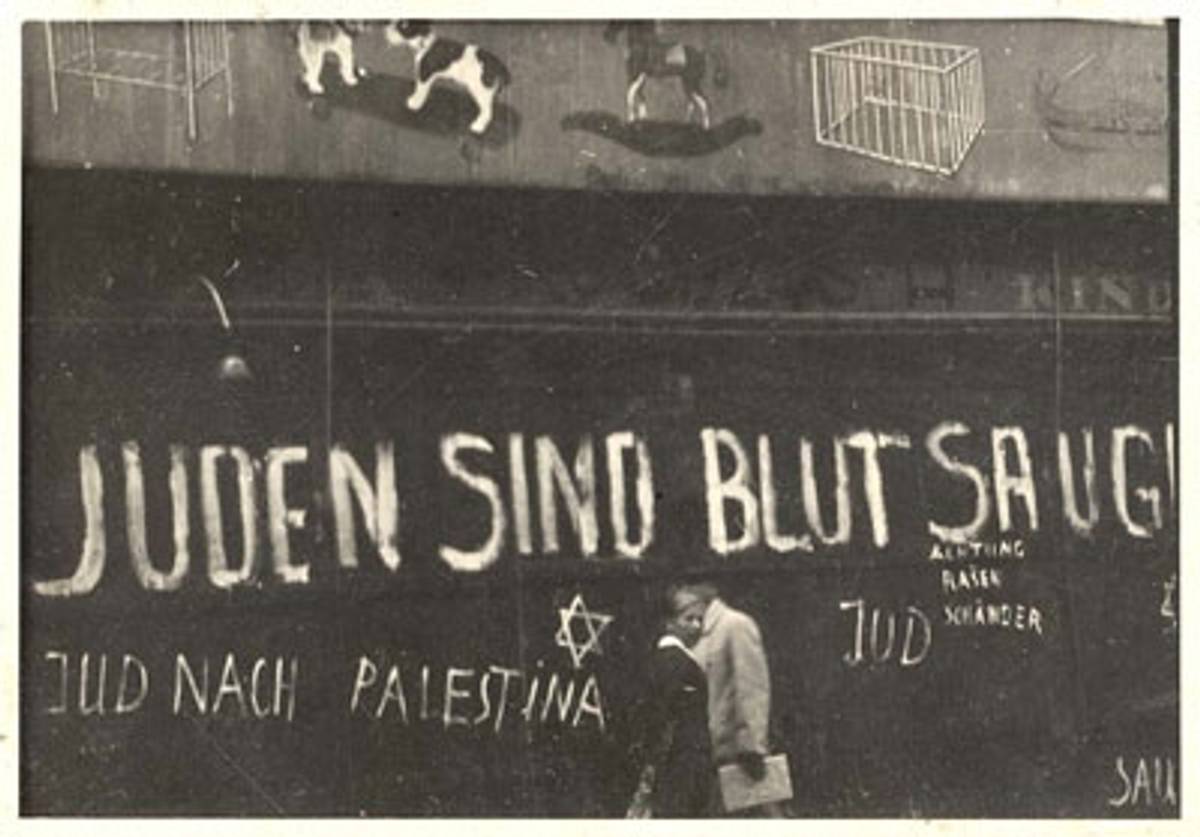

On November 7, 1938, a Jewish youth named Herschel Grynszpan shot the German diplomat Ernst Vom Rath in Paris. Grynszpan’s family, Polish Jews living in Germany, were ordered to be expelled by the Nazi regime and transferred to refugee camps whose conditions were dire. Vom Rath died of his wounds on Nov. 9; word reached Hitler shortly thereafter while attending a dinner commemorating the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch. Upon hearing the news, Hitler left the dinner; speaking on his behalf Goebbels, in essence, called for a pogrom directed against Jews. The expression “spontaneously planned” has been used by historians to describe the unfolding of the events of the next two days.

Within hours of Goebbels’ words, more than 1,000 synagogues were set on fire or destroyed; in 24 hours 91 Jews were killed; and over 30,000 Jewish men aged 16 to 60 were sent to concentration camps where they were tormented and tortured for a number of months. More than 1,000 of those arrested met their deaths in the camps. Rampant looting and extreme violence in a hateful atmosphere marked Kristallnacht, along with arrests, destruction of physical property, physical abuse, and humiliation in more than 1,000 cities, towns, and villages in Germany and Austria.

According to the London Times, “No Foreign propagandist bent upon blackening Germany before the world could outdo the tale of burnings and beatings … assaults on defenceless and innocent people which disgraced that country yesterday.” As “hundreds of thousands danced in wild frenzy while millions watched approvingly,” Church leaders remained similarly silent.

According to Professor Frank Bajohr:

the significance of the November Pogrom as a radicalising factor cannot be doubted. The pogroms that were stage-managed after the murder of Ernst vom Rath … marked both the highpoint and the end of mob anti-Semitism. … They destroyed the basis of the economic livelihood of the Jews within a few months.

Over the past few years my scholarship has focused on extremism and intolerance, particularly the limits of tolerating intolerance. I have become increasingly focused on the bystander because of a conviction that standing by, passively, facilitates extremism.

The bystander is an individual who observes another in clear distress but is not the direct cause of the harm. A culpable bystander is one who has the ability to mitigate the harm but chooses not to. Needless to say, the age and ability of the actor must be taken into consideration.

In the course of my lifetime, I have—like many others—been faced with the dilemma of whether to involve myself when others are in need of assistance. Similar to others, I have made right and wrong decisions; the former are not worthy of discussion, the latter weigh on my conscience.

Once I chose not to assist a homeless adult who was the subject of ugly bullying by a college student; my inaction was inexcusable for I stood but two feet from the incident and could have either prevented it, or at least mitigated its consequences. On a second occasion, I was present at a restaurant when an individual, at the next table, was engaged in an ugly anti-Semitic diatribe. I chose to ignore it.

Regardless of the causes of the bystander’s failure to act, the consequences of inaction can be tragic. The pages of history are filled with painful examples. Extremism benefits from the decision by many to look the other way. Passivity is a human reaction I find unfathomable and unacceptable. I ask three questions: What duty is owed? To whom is a duty owed? And, is a duty owed to one identified as the “enemy”?

***

Yet the crux of the dilemma I seek to address, and hopefully resolve, is not a personal or moral question but rather the nature of an individual’s legal obligation when another individual is in distress, vulnerable and in harm’s way. The Holocaust in general and events in particular including Kristallnacht, the Death Marches, deportations, and thousands of concentration camps, many located in the midst of civilian populations, significantly shape my conviction that creation of a legal standard regarding the bystander is essential.

History shows relying on both a moral compass and impetus with respect to the “right thing to do” is insufficient. The Righteous Among the Nations movingly honored at Yad Vashem offer proof of the willingness of individuals to act bravely in risking life and limb. However, the thousands who sought to aid their fellow man pale in comparison to the millions who turned their backs in the face of both potential and clear harm to others. It is for that reason that I propose imposition of a legal duty to act; relying on moral imperative is simply insufficient.

From the two incidents above, I have learned to be understanding of non-action: After all, if I, who fully understand the consequences of non-involvement, can choose not to act then I must, at least, be sympathetic to others who similarly decide on a “safe course.” However, choosing a “safe course” cannot justify failure to act; history has, unequivocally, repeatedly shown this.

In other words, in accordance with the legal standard I am proposing, the failure to intervene to protect an innocent homeless individual would be deemed a crime, subject to police investigation and prosecutorial discretion. Regarding the anti-Semitism at the restaurant? Ugly, yes, but as it did not morph into incitement, or violence, the speech was protected. In the context of the legal architecture I propose, my silence was not a crime. Should I have said something? As the “should” question suggests the “right thing to do” discussion, each individual can ascertain what is the ethical course of action.

These incidents reflect the spectrum of human interaction and conduct. They pose significant dilemmas for the bystander; proposing culpability predicated on a legal obligation seeks to minimize the gray zone regarding when law mandates action. In other words, duty to care needs to be a legal obligation.

It is imperative to establish legal standards because relying on human nature has proven insufficient. Kristallnacht highlights that human nature is not to save the vulnerable but rather to look the other way or join the mob.

I am convinced that the articulation and implementation of a legal duty to act are essential, particularly in this contemporary age marked by extremism, violence, and hatred. To ignore that reality is to, conceivably, set the stage for, yet again, unimaginable violence against those who are helpless.

In focusing on Kristallnacht, I hope to convince of the need to create legal architecture whereby the duty to care is a legal obligation.

***

Kristallnacht must be viewed as the bitter prelude to the Holocaust. In the words of Herman Goering, “I would not want to be a Jew in Germany.”

According to the historian Martin Gilbert, “Kristallnacht was the culmination of more than five years and nine months of systematic discrimination and persecution.” Jews who comprised less than 1 percent of Germany’s pre-WWII population were singled out by the Nazi regime as the “enemy.”

The exclusion of Jews was largely met by passivity from the population at large whereas former colleagues and neighbors took advantage of the situation to their benefit. Professor Raul Hilberg refers to such individuals as beneficiaries, distinct from bystanders.

It is a matter of debate among historians whether the Jewish population fully appreciated the significance regarding the change in their circumstances; it is clear that the overwhelming majority did not recognize the horrific fate that awaited them. That, however, does not excuse the complicity of the bystander.

Gilbert tells us that during those two days—Nov. 9 and 10, 1938—“hundreds of thousands danced in wild frenzy while millions watched approvingly.” In other words, there were “eyewitnesses in every corner of the Reich” as ordinary German citizens either directly participated in or passively condoned a horrific orgy of violence against Jews, their property, and their synagogues. The condoning, much less participating in unrestrained violence against German Jews by non-Jewish Germans is the essence of tolerating intolerance; it is an absolute violation of the social compact and vividly highlights the extraordinary danger to the vulnerable in the face of bystander passivity.

***

Kristallnacht did not occur in a vacuum. The Nazi regime’s relentless emphasis on racial policy focusing on the improvement of race and racial hygiene targeting habitual criminals, the handicapped, homosexuals, and gypsies—much less Jews—was implemented through a variety of means including sterilization and eugenics. Hitler’s demonization of the Jews resulted in their delegitimization, if not dehumanization as they were, clearly, consistently and loudly defined as “enemies of the German state.”

The Nazification of society required systematic synchronization of all institutions in accordance with Nazi ideology demanding absolute loyalty to the regime and the Fuhrer. The norm, as articulated—primarily by Hitler, Himmler, Goering, Goebbels, and Heydrich—was that Jews endangered “the very survival of Germany and of the Aryan world.” Erasing the shame of the Treaty of Versailles was of paramount importance if not unadulterated obsession.

Hitler’s anti-Semitism was intoxicating, hysterical, and remarkably effective; his speeches were electric, charismatic, and unsophisticated. The themes were consistent: Jews were to be blamed for Germany’s defeat in WWI for Germany’s failed experiment with democracy in the aftermath of WWI and for Germany’s failed economy. The concepts reflected basic principles of fascism, nationalism, and racism; Hitler would return Germany to its glorious roots.

The regime benefited from the passivity of the Church. As Professor Friedlander writes: “During the decisive days … no bishop, no church dignitary, no synod made any open declaration against the persecution of the Jews in Germany.” In the words of Berlin Bishop Otto Dibelius in a confidential Easter missive to provincial pastors: “One cannot ignore that Jewry has played a leading role in all the destructive manifestations of modern civilization.”

According to Professor Friedlander, the Confessing Church, of which Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a leading light, primarily expressed support for non-Aryan Christians and not to Germany’s beleaguered Jewish community. Jews were, literally and figuratively, systematically squeezed out of the social contract. Their unmitigated vulnerability manifests the consequences of society identifying a particular group as the “other” with no duty owed to mitigate the inevitable disaster that awaited members of the group who were, it must be recalled, German citizens.

The measures directly contributed to the aforementioned effort to exclude Jews from the social fabric and reflected the regimes brutality and harshness. The population’s general passivity directly contributed to the successful implementation of the measures below. Re-articulated: The majority of Germans “acquiesced”; the Churches “kept their distance”; and the laws suggest that arbitrary terror was replaced by a “permanent framework of discrimination.”

On March 5, 1933, the Nazis obtained a majority in the Reichstag in accordance resulting from a coalition formed with the German National People’s Party. Shortly thereafter the first concentration camp was established when Himmler officially inaugurated Dachau on March 20, 1938.

On April 1, 1933, a boycott of Jewish shops was ordered by the regime; the boycott largely failed because of the population’s passivity that, according to Friedlander, did not “show hostility to the ‘enemies of the people’ party agitators had expected.” The boycott was proceeded by enactment of the Enabling Act, which granted full legislative and executive powers to the chancellor; in its immediate wake SA forcibly closed shops and attacked and killed Jews.

On April 7, 1933, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service 2 was passed; according to Paragraph 3:

Civilian servants of non-Aryan origin are to retire … anyone descended from non-Aryan, particularly Jewish, parents or grandparents. It suffices if one parent or grandparents is non-Aryan.

On April 11, 1933, Jewish attorneys were excluded from the Bar; on April 25, 1933, the Law Against the Overcrowding of German Schools and Universities was passed, which limited enrollment of new Jewish students to 1.5 percent of new applicants with the overall number of Jewish students not to exceed 5 percent. In September 1933 Jews were forbidden to own farms and to engage in agriculture and in October 1933 Jews were barred from belonging to journalist associations and from positions of newspaper editor.

In September 1935 the Nuremberg Laws were announced at the annual party rally in Nuremberg. The “laws excluded German Jews from Reich citizenship and prohibited them from marrying or having sexual relations with persons of ‘German or related blood.’ Ancillary ordinances to the laws disenfranchised Jews and deprived them of most political rights.” The Nuremberg Laws established fundamental distinctions between citizens of the Third Reich who were entitled to full political and civil rights and subjects who were deprived of those rights.

In the aftermath of Kristallnacht legislation the “First Decree on the Exclusion of Jews from German Economic Life” was enacted that banned Jews from all remaining occupations and called for dismissing those still employed without any compensation. This measure was intended to complete the process of Aryanization.

By 1939, “remaining Jews in Germany had been completely marginalized, isolated and deprived of their main means of earning a living”. In the aftermath of Kristallnacht Hitler began discussing the physical annihilation of Jews; it is for that reason that Kristallnacht is appropriately termed the bitter prelude to the Holocaust. Anti-Semitism, as traditionally understood, was about to be replaced by the ideology of the pogrom as manifested on Nov. 9-10, 1938.

***

The Holocaust magnifies and painfully illustrates the price of passivity. Bystanders suggest a stepping back from making a constructive contribution to mainstream society and facilitating, to varying degrees, harm to otherwise innocent individuals. In other words, a bystander sees yet chooses to ignore. That is the essence of the bystander.

I propose creating three distinct bystander-victim paradigms: 1) Anonymous Bystander, Faceless Victim; 2) Neighbors; 3) Desensitized Bystander, Disenfranchised Victim. In my book, the first theme will be examined through the lens of Death Marches (November 1944-May 1945); the second theme will be examined through the lens of the deportation of Dutch Jewry and the third theme will be examined through the lens of the deportation of Hungarian Jewry.

It has been suggested that the primacy of the bystander’s obligation to self and family outweighs duty and responsibility to the other. In addition, the decision—oftentimes quickly made—to scurry on, thereby deliberately ignoring the needs of others, has been repeatedly offered as reflecting the reality of human interaction, or more correctly of human “non” interaction.

What is particularly problematic in the effort to create a legal standard addressing this issue is determining the degree to which the state can impose a “positive” duty on members of society. Nuance is essential to a full discussion regarding the bystander; different circumstances and conditions must be taken into consideration when articulating and implementing a duty to act paradigm. Creating, or allowing, a wide range of exceptions to an agreed upon rule facilitates unwarranted “wiggle room” that, ultimately, provides justification for a lack of intervention and involvement.

The perpetrator bears the greatest degree of culpability for the harm that befalls the victim; however, as the Holocaust clearly demonstrated the complicity of the bystander greatly facilitated the perpetrator’s actions and its consequences. It is that complicity that is at the core of our undertaking; in proposing legal standard that enables prosecution of the bystander the assumption is that there is a need to clearly articulate an enforceable duty to care. That is the essence of the social contract. To not protect the vulnerable and at-risk members of society—regardless of their status, position, and class—is a resounding rejection of the social contract. That, for me, is the critical lesson I propose we take away from Kristallnacht.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Amos N. Guiora is a professor of Law at SJ Quinney College of Law, University of Utah. His book Complicity: The Role of the Bystander in the Holocaust is forthcoming in 2017 from Ankerwycke Books.