Israel Provides a Third-World Education for Bedouins

Israeli Arabs at a Crossroads: high dropout rates and low achievement leave many children at a dead end

Wafa Abu Ammar was at work when the terrible phone call arrived. Her nephew had been shot and critically injured on the Egyptian border, she was told. She left everything and rushed to the hospital. Fifteen-year-old Nimr Abu Ammar had cut class to join his uncles at the construction site of the new Israeli border fence with Egypt. An Egyptian soldier opened fire and shot Nimr, who was out serving coffee to his family members and may have crossed the border. The boy was pronounced dead on arrival at Be’er Sheva’s Soroka hospital.

Nimr’s death made waves beyond his local community, perhaps due to the international nature of the incident. What was the teenager doing out in the middle of the desert on a school day? one member of Knesset wondered. At the hospital, Nimr’s father, Bassam, accused the Ministry of Defense of not providing army protection to the workers. But the boy’s name was soon flushed out of the news cycle. The Abu Ammar family received no government compensation for his death.

“He was a quiet, well-behaved, kind boy,” said Abu Ammar, who works as head of the youth department at the local council of Laqiya, a Bedouin township of 12,000 north of Be’er Sheva. “He didn’t find his place in school, but never spoke about it. It was up to us to identify these issues.”

Nimr Abu Ammar was in no way unique. While Bedouin schools downplay the scourge of truancy, placing it at 2 percent to 5 percent, the Ministry of Education reports a high-school dropout rate of up to 27 percent, the highest in the country. According to the Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute, an Israeli nonprofit, the Bedouin dropout rate reached a staggering 36 percent in 2014, significantly higher than the 22 percent average among Israeli Arabs and 16 percent in the general population. Bedouins are also Israel’s youngest population, with over two-thirds under the age of 21.

Muhannad, a 27-year-old Laqiya resident who works as a truancy officer at the Ministry of Education, is tasked with tracking absent students and reporting them to the government. When a school contacts Muhannad, he phones the parents to inquire about the child’s whereabouts. If that doesn’t work, he invites the parents for a chat at the municipal council building. Final measures include a personal visit to the student’s home.

“Everything I do is recorded in the computer of the education ministry,” said Muhannad, declining to reveal his real name as he is not authorized to speak to the press. According to Muhannad, even young Bedouin children often miss school due to a lack of busing and difficult access from their distant communities.

“The schools are first to deal with truancy,” he said. “I won’t even know if a child is missing for the first week.”

Wafa Abu Ammar—one of 26 children of her polygamous father, and nine full siblings (her mother was the first of three wives)—was never truant. A straight-A student, she would often ask her primary-school math teacher if she could teach the class instead of him. But of all her siblings, only one other brother entered university. The rest dropped out of high school to get jobs.

“When youngsters leave to work, they feel independent and mature,” she explained. “The same story repeated itself with my nephew Nimr. The eldest son of young parents, he just didn’t fit in.”

With an average fertility rate of 5.5 children per woman (down from 7.14 in 2007), Bedouin parents cannot guarantee quality education for their children, Abu Ammar argued. “You can’t have an educated family with 13 or 15 children. Some of them will inevitably miss out on school and go to work.”

Abu Ammar left her hometown to study nursing in Ashkelon, becoming the first woman from her tribe to receive a college education. A few years later, she would find herself teaching sexual education at a high school in Hura, a nearby Bedouin town, where she fell in love with the field of education.

“I found I could give more to that age group than to older people or to patients at the hospital,” she said. When the position for head of the youth department in her hometown was advertised, she felt like the job was created for her. Today, she is planning to establish a local center for high-school dropouts and at-risk youth, offering both formal and informal education, “so that we don’t have more Nimrs, God forbid.”

Unmarried at 33, Abu Ammar claims her choice to study precluded the option of an early marriage. “That’s the price one pays for going to university. Men are scared of an educated woman, of a leader,” she said. “I’ll most likely become someone’s second wife.”

***

Like Abu Ammar, Ibrahim Nsasra was born to a polygamous family in Laqiya. One of 32 siblings, he described his life course as “against all odds.” Nsasra was trained as a physical education teacher at his parents’ request, who were both illiterate. At 21, he entered a swimming pool for the first time in his life, because none existed in his hometown. But upon graduation, Nsasra decided to abandon the field of education and start a transportation company with his brothers.

In 2010, he attended the prime minister’s conference in Haifa dealing with employment in the Arab sector. “The entire way home I was thinking about how to tackle this problem,” Nsasra said. Ten months later, he bought a factory in the Bedouin city of Rahat and started manufacturing meals for local school children. With Bedouin female unemployment at 82 percent, he wanted to give jobs to local women reluctant to leave their community for work. Today, he boasted, the factory employs 40 women and 10 men, producing 10,000 meals a day with government funding.

‘That’s the price one pays for going to university. Men are scared of an educated woman, of a leader. I’ll most likely become someone’s second wife.’

As a local councilman in 2013, Nsasra chose the long-neglected education portfolio, just as he started his graduate degree in public policy at Hebrew University. “In the past, the strength of the Bedouin tribe rested in its numbers,” he said, referring to his outsize family. “Today strength lies in education, profession, achievements, not in who you belong to.”

That understanding led Nsasra and a group of Bedouin colleagues (and one Orthodox Jew) to create the Tamar Center in 2015. Located in Beersheba, the Center strives to improve scientific and technological education among Bedouin High School students and reduce dropout rates. Bedouin high schoolers, he learned, hardly ever take math and English exams at a level enabling them to study engineering or sciences in college.

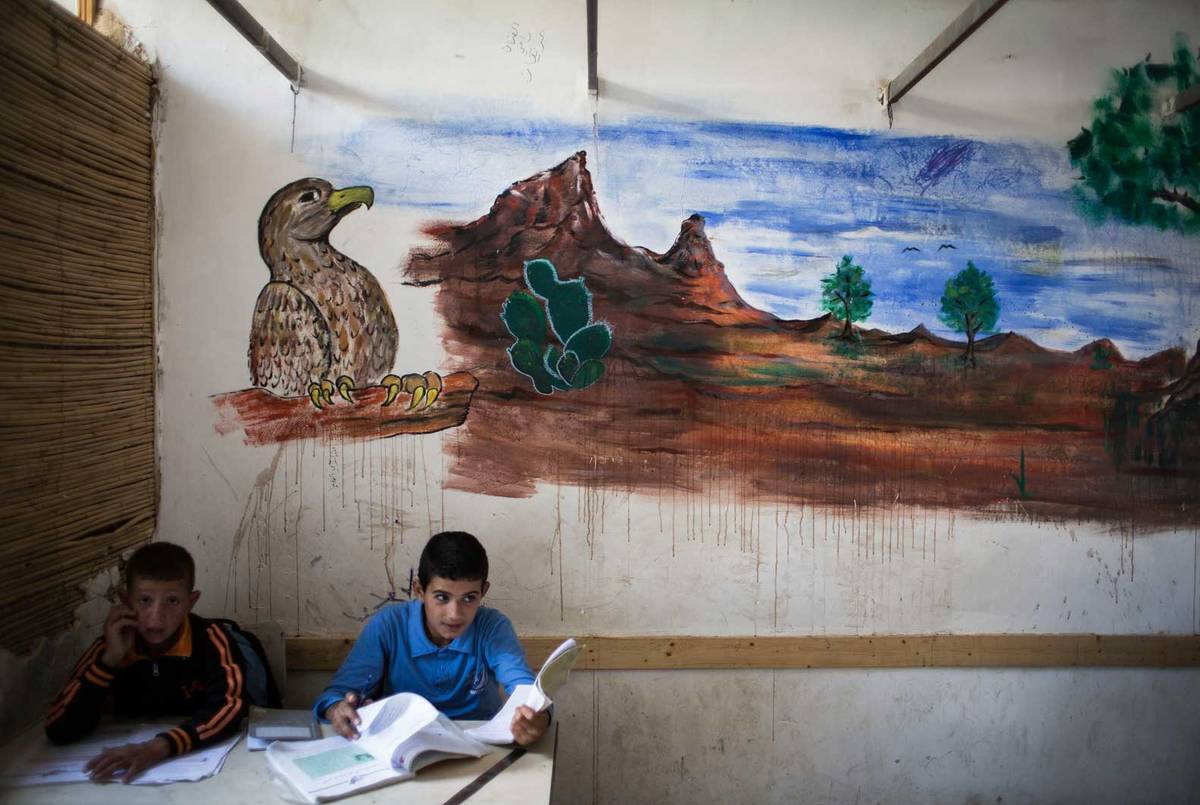

“The quality of teaching in Bedouin schools is extremely low,” Nsasra said. “ It’s like the education system of a third-world country.”

The pilot program of Tamar Center, launched last year, gave 60 Bedouin 10th-graders the opportunity to study math, English, and sciences at the highest matriculation level on Fridays, their day off from school. The weekly classes are supplemented with summer study marathons and visits to science museums and Israeli mega-companies like Teva and Israel Chemicals. Today, the center operates in two additional Bedouin villages and serves 200 students from across the Negev.

“Why should we import 5,500 engineers from abroad for our high-tech industry when we have a 50 percent unemployment rate here in the Negev?” Nsasra wondered, referring to a government plan to issue thousands of work visas to foreign engineers to answer local demand.

One of the secrets of the program’s success is the responsibility parents and students share for their academic achievements. “There are no free meals,” Nsasra said, noting that every student must pay 100 shekels (about $25) a month as a “seriousness fee.”

“If a student doesn’t show up one Friday, his parents will get a phone call asking where he is. That’s something that [Bedouin] schools don’t do. We also hold parent-teacher-student meetings, which is normal in Jewish society but is unheard of among Bedouins. It’s a completely new language,” he said.

“We tell the parents: ‘Don’t teach your child English or math. Simply speak to them, let them know what you do, give them moral support through adolescence.’ ”

That kind of support, both at home and in school, is probably what Nimr Abu Ammar lacked, Nsasra said. “A student who drops out of school is a testament to the system’s failure. Such a student is someone disinterested by school, disinterested by his teachers. I know of students who go to school crying,” he said. “Before focusing on grades, we should help students love their school. We should reward schools with low dropout rates.” He also believes in the need for more diverse kinds of schools, such as for arts or technology.

As for Nsasra, the education he lacked in school was transmitted by his traditional upbringing. “My late father had a herd of sheep. Every weekend we would travel with our tent to Kiryat Gat and guard the herd. That’s where I learned responsibility in a way I couldn’t learn at any school.”

Now that Tamar Center’s excellence program is well underway, Nsasra and his colleagues are working on reducing truancy and the dropout rate. They are also creating a gap-year program for Bedouin high school graduates that would immerse them in the Hebrew language and Israeli society.

“I want my Bedouin students to realize it isn’t just them who gets screwed,” he concluded. “Maybe Ultra-Orthodox Jews also get screwed? Maybe secular Jews do? And maybe no one does and it’s their responsibility to make a difference?”

***

This is the third dispatch in a Tablet series, Israeli Arabs at a Crossroads: The Negev. The fourth appears tomorrow.

Elhanan Miller (@ElhananMiller) is a Jerusalem-based reporter specializing in the Arab world.