Jews Get to Define Anti-Semitism

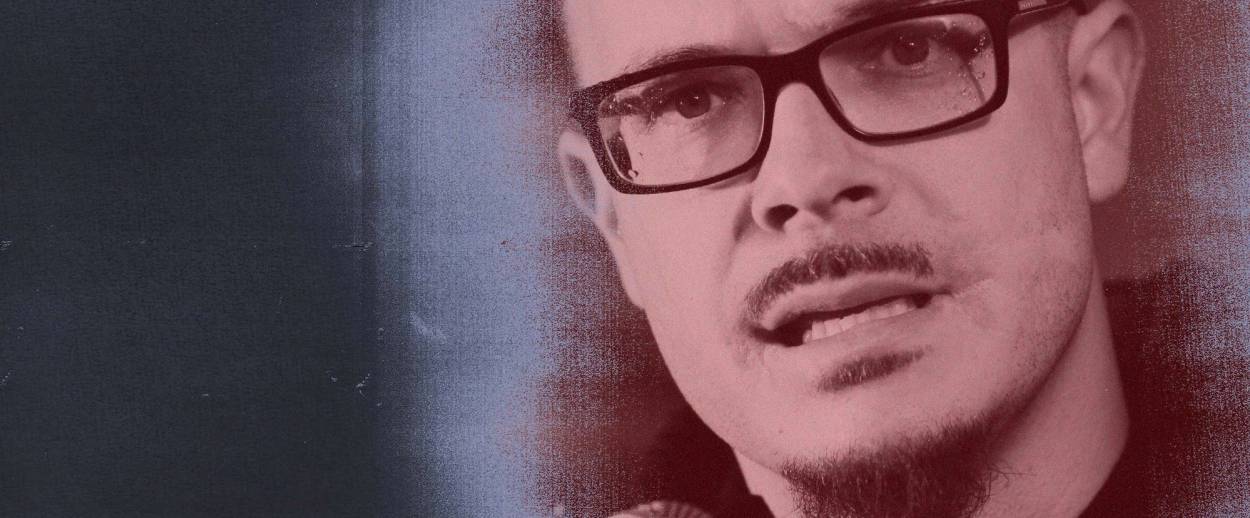

Not Shaun King

A central tenet of anti-oppression work is that marginalized communities are the authors of their own experiences. Those who experience a specific oppression get to define it, and how it shows up in their daily life in big and small ways. I cannot possibly grasp all of the ways racism shows up throughout the life of a person of color. As much as I may try, my white privilege will inevitably blind me to how simple daily acts like driving my car, walking my baby in the park, or waiting in a Starbucks can quickly become dangerous. Conversely, my husband as well as male friends and colleagues may struggle to understand how gender shows up in my daily life, so they should listen to me when I describe what my experiences are and how they affect me.

Anti-Semitism, like most forms of systemic oppression, is difficult to see if you don’t experience it directly. If you have never been asked to leave an anti-war protest because you were wearing a Magen David necklace, you may not understand how we are pushed out of movements. If your house of worship does not require 24-hour private security, armed guards, and bag searches to enter, you may not understand how we move through the world. If your family doesn’t include people who were ghettoized, beaten, starved, and gassed to death in concentration camps, you probably don’t experience a neo-Nazi march in Charlottesville—or “pro-Palestinian” demonstrators burning the Israeli flag and chanting for the deaths of Jews in Israel—the same way that we do. If a passerby has never screamed at a crowd of worshippers, or drawn swastikas or rats on your spiritual home, or accosted you in your workplace and started screaming about purported Israeli atrocities or “Likudnik” conspiracies, you will not understand our fear of being Jewish in public. If you’ve never spent an afternoon on the phone with an anti-extremism expert discussing whether or not being featured on a neo-Nazi website is cause for alarm, you don’t understand what Jewish writers regularly encounter during their workdays. If you have never been told to tolerate being called satanic or evil, or compared to an insect for the sake of coalition building or political unity, you may struggle to understand why many of us are so angry at the progressive movement. I have experienced all of the above.

Anti-Semitism attempts to chip away at our voices, our culture, our careers, our relationships, and ultimately our humanity. If you haven’t lived it, in all of its insidious silencing, it is difficult to understand. Despite the FBI’s yearly hate-crime statistics, it can be difficult for people who are not Jewish to believe that anti-semitism is real, violent, and scary—the same way that it can be easy for some to callously dismiss the lived experience of women, people of color, and gay, lesbian and trans people. Which is why those who carry the banner of justice—and especially those who present themselves to others as models for and leaders of progressive movements—should always be listening hard to historically oppressed groups, Jewish or otherwise.

Shaun King is an example of a very public failure to live up to anti-oppression values in the social justice movement. When Jewish-Americans expressed anger that King’s friend, Tamika Mallory, attended events and partnered with Louis Farrakhan, his response was deeply inappropriate. He accused Jews who were angered by her behavior of being liars. When he was gently called in by Jewish supporters who expressed both admiration and disappointment, he said he “would not allow” Tamika Mallory to be accused of anti-Semitism. When Jewish musician Regina Spektor, who performed at the Women’s March in L.A. and had supported King’s efforts in the past, expressed her frustration and pain at the situation, he blocked her. He then proceeded to show us the kinder, gentler side of the Nation of Islam by tweeting pictures of Farrakhan hugging a young man who says he saved his life.

Shaun King should have stopped and listened to Jewish voices, instead of trying to use his enormous platform to try and shut us up. He doesn’t get to decide what anti-Semitism is, how it shows up in our lives, or when and how we get to talk about it. Farrakhan has called us satanic and evil, and claimed that we are not even truly Jews. Yet King’s friend called Farrakhan the “greatest of all time” and refused to condemn his virulent and well-documented anti-Semitism. Shaun King doesn’t get to decide how we feel about her actions.

When leaders fail to live up to their values, there must be space to apologize, learn, and earn redemption. But if we are going to fight oppression and create a more just world we need to name oppression and hatreds, and be honest about the complex systems that keep historically marginalized groups down. That becomes more difficult when an oppression falls outside of your realm of experience and relationships.

I have great respect for King’s work identifying white supremacists in Charlottesville and holding them accountable. This is dangerous, difficult, and commendable work. But sometimes the hardest work is calling in our friends and asking them to change. King centers on himself, his feelings, and his own friendships . When faced with hatred in his own circle, he fails to live up to the moral standard he has helped to set. He claims to stand with the Jewish community, but turns on us and calls us liars when we want accountability from progressive leaders. If he is the bridge builder he claims to be, he should be facilitating dialogue, amplifying our voices and de-centering himself. When we are hurt, angry and in need of allies, he is shutting us down instead of lending a hand.

King does not face the consequences of the rising anti-Semitism he dismisses and excuses. We live it every day, as do our children. Jewish parents in the United States and globally are deeply concerned with the safety of our children within Jewish institutions, especially since synagogues, JCCs, and Jewish schools have been targeted by bomb threats, graffiti, and violent attacks. Because anti-Semitism is intersectional, and layers with other forms of oppression, these intersecting oppressions can have devastating impacts, such as the case of Nora Nissenbaum, who has suffered anti-Semitic and misogynistic threats at school so severe she is suffering from PTSD. While parents across the country fear for their kids’ safety at school, the intersecting identities of being female and Jewish put Nora at additional risk.

As we seek to protect ourselves from those who target us, we also face the added complexity of ensuring that security forces, both private and public, will protect our children and our institutions without endangering, intimidating or in anyway excluding Jews of color. During a time when so many historically oppressed communities feel under attack and marginalized, it is more important than ever that we listen and amplify voices describing how oppression is showing up in their lives.

King should have asked some of the many Jews of color in America how his rhetoric affects their lives, and how it puts our children at risk. He should have privately and publicly worked to rebuke hatred, build bridges and facilitate healing. Instead he has sought to silence, belittle, and justify our pain. Given that behavior, it becomes nearly impossible for King to engage on difficult subjects like Israel with our community without being treated with suspicion.

King has justified rhetoric that calls Jews subhuman. So how can we trust his intentions when discussing the nuanced, painful, and volatile situation in Israel? He has room for Farrakhan and BDS in his political life, but no room for Regina Spektor. This furthers the breach in trust and respect between him and many members of the Jewish community and ultimately weakens the cause of combatting white supremacy. This is damage that King has done to work that affects us all, for reasons that are ultimately self-centered and contrary to the basic tenets of anti-oppression work.

King has said he would give his life to fight anti-Semitism. I appreciate the sentiment greatly, but what seems more important at this moment is that he listen to those whose lived experiences he has dismissed and blocked. When I want to better understand and fight police brutality I look to King. When we talk about anti-Semitism and the pain it causes, he should listen to us.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Carly Pildis is the Director of Grassroots Organizing for the Jewish Democratic Council of America, and an advocacy professional based in Washington, D.C. Her Twitter feed is @carlypildis, and her website is www.carlypildis.com.