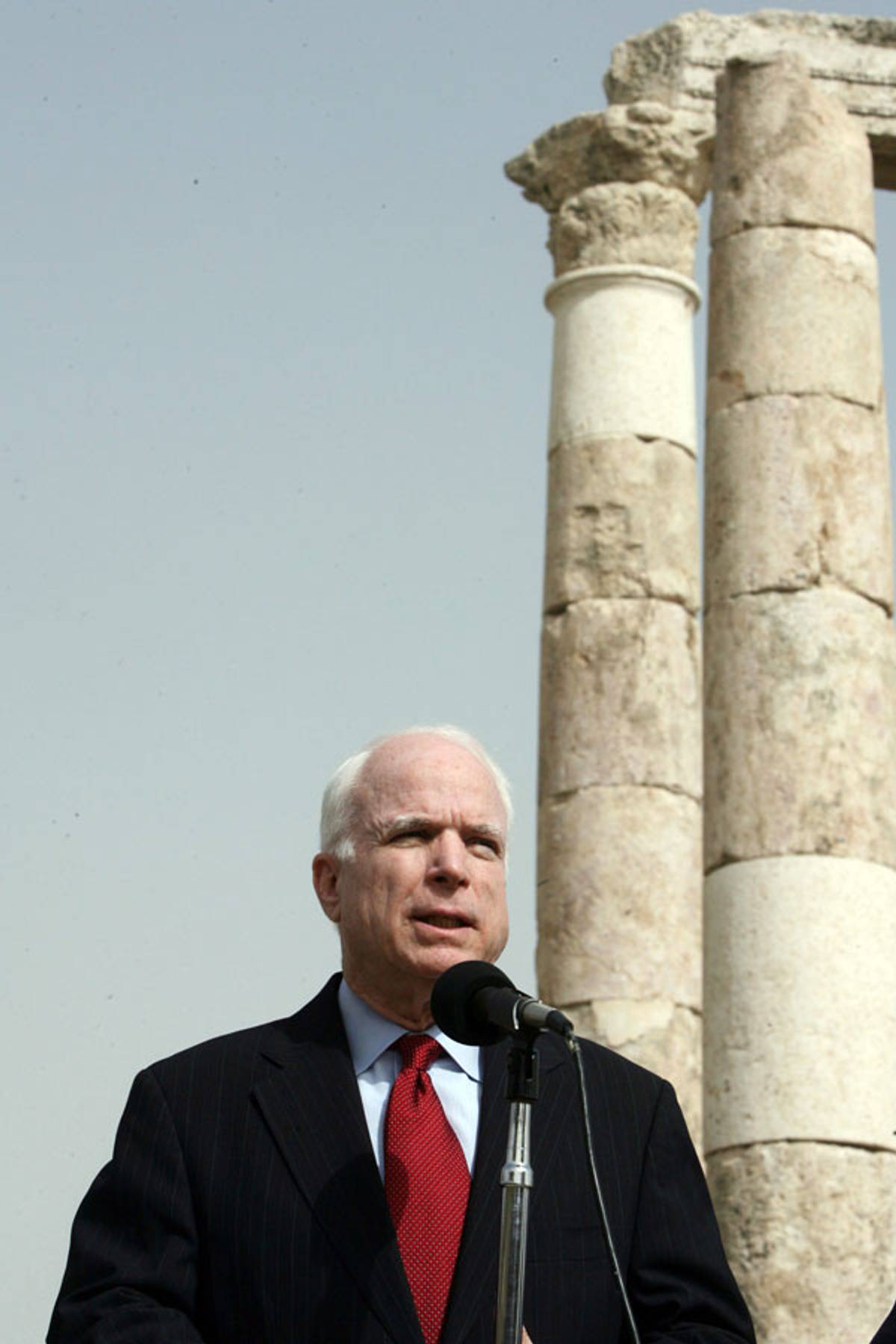

McCain and the Roman Precedent

The late senator embodied the classical republican virtue of aristocracy, yet he was not above the barbarous opportunism that brought us Sarah Palin, and her political heirs

John S. McCain was a noble Roman out of Plutarch, which is to say, a man of far-visioned republican virtue who was also, in the Roman style, shockingly barbarous; and, in this way, he was the most American American who ever lived. His story in Vietnam is surely the most extraordinary to come out of that war, but to judge it seems impossible. Was America right to have fought in Vietnam? America was obviously right, from one angle. The war was fought to spare the Republic of South Vietnam from having to undergo the experience of North Vietnam—fought to allow South Vietnam to tread in the ultimately democratic and prosperity-making path of South Korea and therefore to make a better world. But mass death was the only result, followed by, willy-nilly, the North-Vietnamization of the South. Not one good and decent thing was achieved, only horror, of which the worst may well have been the air campaign over North Vietnam, an atrocity by definition, which happened to be John McCain’s part in the war. He ended up in a North Vietnamese jail because he had been shot down over North Vietnam. It is true that he bore his extreme sufferings with magnificent heroism, something beyond imagining. But what can we make of his Vietnam experience, taken altogether? The righteous and the wrong, the idealism and the crimes, the noble intentions and the disastrous realities—nothing adds up, and history is not a balance sheet.

Was Iraq destined to be Vietnam, version two? To liberate Iraq from Saddam Hussein was good, in principle, except that, under George W. Bush’s command, the liberation was bound to be, in practice, as bad or worse than the tyranny. And yet, it is tempting to wonder what might have happened if, in the 2000 Republican primaries, McCain had successfully resisted Bush’s very ugly primary campaign, and had gone on to the White House. Wouldn’t McCain have understood the military challenge more intelligently? There is reason to think so.

Back in 2003 and ’04, after a few months of Donald Rumsfeld’s “military transformation” theory in its Iraqi application, nearly everyone in the American political class seemed to freeze, as if in terror. Bush appeared to be mesmerized, blindly continuing the forward march into calamity. The Republican Party as a whole appeared to be mesmerized in defense of the mesmerized president. The Democratic Party, having in its majority supported the original invasion, chose right away to lapse into anti-war virtue, with folded arms and nothing to propose. It was a spectacle of mass irresponsibility, with redeeming counterexamples offered only by two national figures, alone among the politicians, who stepped forward after a while to make practical suggestions—namely, Joe Biden (who proposed that Iraq be divided into provinces, Sunni, Shiite, and Kurdish, to solve its political problems). And John McCain (who proposed sending additional American troops in a so-called surge, to offer protection to Sunni tribes who would turn against the Sunni terrorists). I do not know whether Biden’s proposal was viable or not, but it seems to fair to say that, either way, he displayed an entirely rare vocation for leadership by at least trying to come up with a plausible proposal. And this was still more so in the case of McCain.

The mesmerized president did, after all, come around eventually, and the “surge” went into effect, which all but eradicated the Sunni terrorists. The Iraqi state was said to stabilize. The war appeared to have been won, at least militarily—or so implied Biden, after he had become vice president. It was just that President Barack Obama, having defeated McCain in the 2008 election by promising to end the war—and to do so responsibly—fulfilled only the first half of the promise, and withdrew almost all of the no-longer war-fighting American troops. And next came the caliphate. Wouldn’t McCain’s advice have avoided those disasters?

Even the Obama-Biden administration had to agree, after a fatal pause, that American troops and air power did need to return, in order to support the Iraqis in a struggle that ought not to have been necessary. It was just that, by then, with the 2008 election behind him, McCain had made it impossible to suppose that he was a man of sober judgment. His Sarah Palin decision represented, after all, one more lapse into savagery. He decided on her because, more acutely than anyone on the Democratic side, he saw what had happened to the Republican masses—saw that a large public had descended into a nihilism; had abandoned any concern with the traditions and virtues of the American republic; had lost any feeling for America as a whole, so long as a demagogue could be found to rail at the educated class and the elites. And McCain, who was the descendant (it is said) of an adviser to George Washington, and was the son and grandson of admirals, and was a graduate of Annapolis and a storied hero—McCain, who was an American aristocrat in the best Roman republican sense of the word—decided to throw in with the pitchfork peasants. Barbarism beckoned. It was opportunism. A more dismal possibility: It was an adventure, something from his hell-raiser youth, perhaps.

His career reminds us that it was not the worst of the Republican Party who, some years later, delivered the party and the nation into our present crisis. It was McCain himself and his distinguished neocon advisers who did it, or, at least, who prepared the way. Their achievement was to advise the nation that a prospective president need be no more qualified than a cocky and cheerful Sarah Palin. And then, when the time came and a Palin type was finally elected, McCain, who would have made himself look good by reacting with fury, reacted, instead, with a display of miserable calculation, such that, at one moment, he was anti-Trump, and then was Trump’s supporter, and then his opponent once again. McCain’s Arizona colleague, Sen. Jeff Flake, spoke articulately about Trump and the damage he had done to the Republican Party and the nation. But McCain confined his responses to a thumbs down and occasional sharp remarks that, even if everyone has always savored the non-politician tone, never rose to the level of sustained and intelligent analysis.

It is good to remember that, in distant parts of the world, John McCain was deeply admired, and that was because, whenever he escaped the shadows, he stood more clearly than anyone else in recent years for the concept of America’s commitment to the worldwide cause of resistance to despots. Wherever could be found a small nation, trying to fend off the tyranny of the large and powerful, there could be found John McCain, usually in person. Little delegations of the oppressed were always making their way to his office in Washington. The Chechens, who are friendless everywhere else, had a friend in McCain. The Georgians, likewise. It was not really any different with the Israelis.

McCain spent a fair amount of time in Georgia, and, on one of his trips, a French friend accompanied him on a tour of the Georgian mountains and discovered that, as the hours passed, the senator, having let his hair down, wanted to confess to a private ambition. He would have liked to be Hemingway in Spain. I interpret this to mean: John McCain would have liked to be the hero of For Whom the Bell Tolls, who leaves peaceful America behind to volunteer in the republican cause in the Spanish Civil War, battling the fascists. This was an expression of the American democratic internationalism taken as a personal vocation, and not just as a foreign-affairs policy—a democratic internationalism as a guide to life, and not merely to politics. It was a grander idea than everyone else’s in modern political America. It was more romantic, more stirring, though visibly more dangerous, and, in the version that McCain lived, it turned out to be appalling and magnificent in overlapping phases, like America herself.

***

To read more of Paul Berman’s political and cultural criticism for Tablet, click here.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.