The Future of the Pittsburgh Synagogue Massacre

Is American anti-Semitism really distinctive from that of other diaspora countries? Just how worried should we be?

In the early morning hours of Oct. 12, 1958, exactly 60 years to the month before the massacre of 11 Jews in Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue, a nitroglycerine bomb equal to 50 sticks of dynamite tore apart the Temple, the oldest and most distinguished Reform congregation in Atlanta. “The sound of the blast traveled heavily for miles,” Melissa Fay Greene recounts in her all-too-timely history of that sadly forgotten anti-Semitic episode, The Temple Bombing. The Confederate Underground, the group that claimed credit for the attack, promised in a telephone call “to blow up all Communist organizations. Negroes and Jews are hereby declared aliens.”

Before the rubble had even been cleared, politicians began to debate where to place responsibility for what was described as one of the worst incidents of anti-Semitism in all of American history. Ralph McGill, the courageous liberal editor of The Atlanta Constitution, blamed the demagogic rhetoric of the state’s segregationist politicians. Segregationists responded with outrage, suggesting that the bombing was instead part of a “conspiracy to bring national discredit upon the South at a time when it is fighting integration of its public schools.” The president of the militantly right-wing Citizens Councils of America insisted to reporters that efforts to pin the blame on groups such as his were entirely unwarranted, for “we’ve got a hell of a lot of Jew members.”

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, for his part, trod carefully between his conservative Southern supporters and liberals encouraging him to express outrage. “I think we would all share in the feeling of horror that any person would want to desecrate the holy place of any religion, be it a chapel, a cathedral, a mosque, a church, or a synagogue,” he piously declared soon after the bombing. He later opined that the Confederate Underground consisted of “a bunch of Al Capone gangsters who soil the good name of the Confederacy.” In the end, two Georgia juries failed to convict anyone. One of the most infamous anti-Semitic incidents in all of American history remains officially unsolved.

The story of the Temple bombing leaped to mind when I heard the horrific news from Pittsburgh. The parallels are uncanny: In both cases, extremists with longstanding anti-Semitic tendencies took up arms and targeted synagogues amid an incendiary political atmosphere charged by extreme divisiveness and demagogic rhetoric. Meanwhile, traumatized Jews, in both cases, expressed alarm at what the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in 1958 described as “a frightening parallel to the coming of Hitler to power in Germany.”

The early years of the Civil Rights Movement resulted in a spate of “bombing outrages” directed against black and Jewish institutions alike. “In the twelve months before the bombing of the Temple in Atlanta,” Melissa Fay Greene recounts, “eleven sticks of dynamite were found at a temple in Charlotte; a synagogue in Miami and the Nashville Jewish Center were bombed on the same day; undetonated dynamite was found at a temple in Gastonia, North Carolina; a Jacksonville, Florida, synagogue was dynamited; and dynamite with a burnt-out fuse was found at Temple Beth-El in Birmingham, Alabama.” All in all, some 10 percent of the bombs planted by extremists between 1954 and 1959 targeted Jewish institutions—synagogues, rabbis’ homes and community centers. Most of the other 90 percent targeted African-American institutions. Though extremists tended to strike late at night to avoid detection, which limited injuries, the Anti-Defamation League warned that loss of life was inevitable unless federal authorities went after the bombers. Seeking to spur just such federal action, and in response to the nationwide outrage over the Temple bombing in Atlanta, leading Americans including the evangelist Billy Graham and Senator John F. Kennedy, formed an organization entitled Americans Against Bombs of Bigotry.

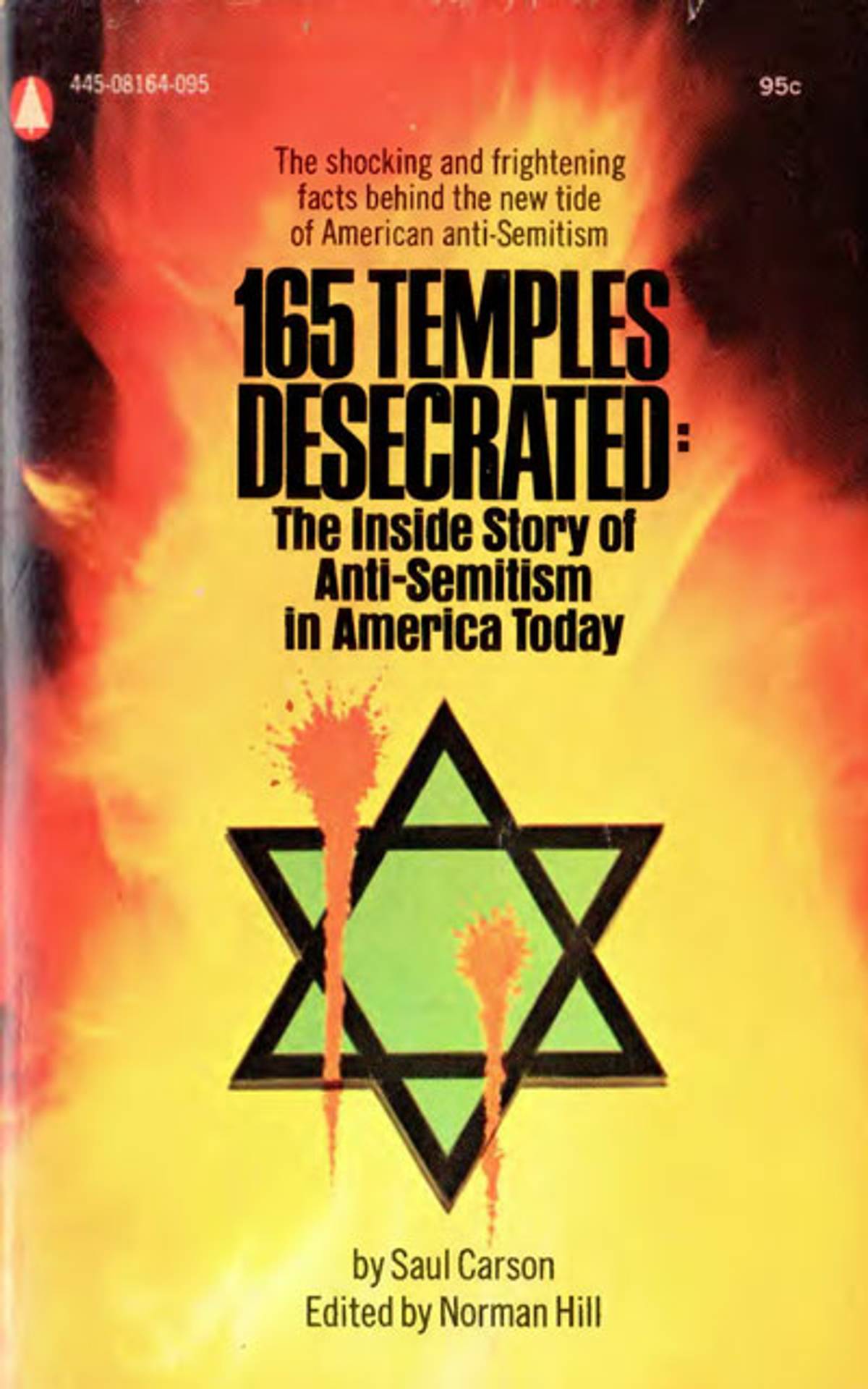

This well-meaning but powerless organization closed its doors within two years. In the mid-1960s, however, violent attacks against Jewish institutions resumed. A widely distributed paperback with the explosive title 165 Temples Desecrated, published in 1971, chronicled the attacks that took place just between 1965 and 1970. The deadliest occurred on Dec. 20, 1965, in Yonkers, New York, when “twelve people, including nine children and three adults died in a suspicious fire that swept the Yonkers Jewish Community Center. Eight other persons were injured.” The best-known and most notorious took place in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1967, where white supremacists bombed Temple Beth Israel’s newly dedicated house of worship and then, two months later, returned to bomb the home of the temple’s rabbi, Perry Nussbaum.

Previous generations of young American Jews have experienced the same “loss of innocence” now being witnessed in the wake of Pittsburgh. For example, back in the late 19th century, when the term “anti-Semitism” first took root and American Jews experienced heightened social discrimination, many a young Jew despaired at how conditions in their new homeland had unexpectedly deteriorated. “Gradually, but surely, we are being forced back into a physical and moral ghetto” a young 35-year-old professor at Columbia University named Richard Gottheil explained. “Private schools are being closed against our children one by one; we are practically boycotted from all summer hotels—and our social lines run as far apart from those of our neighbors as they did in the worst days of our European degradation.” Resurgent anti-Semitism turned many young Jews inward in the late 19th century. They ultimately channeled their anger into a “great awakening” that revitalized American Jewish life.

Today, the mood in the American Jewish community seems darker. Just as after the Temple bombing in Atlanta, the specter of the Holocaust haunts the community. Syndicated cartoonist Rob Rogers, formerly with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, went so far as to compare the Tree of Life synagogue massacre to Kristallnacht, the so-called Night of Broken Glass (Nov. 9-10, 1938) which The Holocaust Encyclopedia described as “the most modern pogrom in the history of anti-Jewish persecution and an overture to the step-by-step extirpation of the Jewish people in Europe.” In a surprisingly short time, reports concerning the “death of American anti-Semitism” have given way to apprehensions that the Holocaust might soon happen here.

Prudent as it is for Jews to be circumspect given what has occurred, it nevertheless bears recalling that critical factors still distinguish America from other diaspora countries where Jews have lived. I set forth some of these factors back in 1981, when in the wake of neo-Nazi threats to march in Skokie, Illinois, and other manifestations of domestic anti-Semitism, the idea that “it might soon happen here” previously emerged. Time has not diminished the significance of those mitigating factors, though when it comes to hatred no guarantees are unbreakable. Still, these five factors still render American anti-Semitism distinctive:

In America, Jews have always been able to fight back against anti-Semitism freely. Never having received their emancipation as an “award” (which was the case in Europe), Jews have had no fears of losing it. Instead, from the beginning, they made full use of their freedom, especially freedom of speech. As early as 1784, a “Jew Broker,” probably the famed Revolutionary-era Jewish bond dealer, Haym Salomon, responded publicly and forcefully to the anti-Semitic charges of a prominent Quaker lawyer, not hesitating to remind him that his “own religious sectary” could also form ”very proper subjects of criticism and animadversion.” A few years later, Christian missionaries and their supporters faced Jewish polemics no less strident in tone. Where European Jews often prided themselves on their ”forbearance” in the face of attack, Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, the great Reform Jewish leader, once boasted that he was a “malicious, biting, pugnacious, challenging, and mocking monster of the pen.” In more recent times, Jewish defense organizations have taken on anyone who maligned Jews, including national heroes like Henry Ford and General George S. Patton, as well as presidents of the United States.

American anti-Semitism has always had to compete with other forms of animus. Racism, nativism, anti-Quakerism, Anglophobia, Islamophobia, anti-Catholicism, anti-Masonry, anti-Mormonism, anti-Orientalism, , anti-Teutonism—these and other waves of hatred have periodically swept over the American landscape, scarring and battering citizens. Americans have long been extraordinarily pluralistic in their hatreds. Precisely because the objects of hatred have been so varied, hatred has generally been diffused. No one outgroup experiences the full brunt of national odium. Furthermore, most Americans retain bitter memories of days past when they or their ancestors were themselves the objects of malevolence. The American strain of anti-Semitism is thus less potent than its European counterpart, and it faces a larger number of natural competitors. To reach epidemic proportions, it must first crowd out a vast number of contending hatreds.

Anti-Semitism is more foreign to American ideals than to European ones. The central documents of the Republic assure Jews of liberty; its first president, in his famous letter to the Jews of Newport, conferred upon them his blessing. The fact that anti-Semitism can properly be branded “un-American,” although no protection in the formal sense—the nation has betrayed its ideals innumerable times including in our own day—still grants Jews a measure of protection. Elsewhere anti-Semites could always claim legitimacy stemming from times past when the Volk ruled and Jews knew their place. Americans could point to nothing even remotely similar to that in their own past.

America’s religious tradition—what has been called “the great tradition of the American churches”—is inhospitable to anti-Semitism. Religious freedom and diversity, church-state separation, denominationalism, and voluntarism, the key components of this tradition, militate against the kinds of us-them dichotomies (“Germans and Jews,” “Poles and Jews,” etc.) so common in Europe. In America, where religious pluralism rules supreme, there has never been a single national church from which Jews stand apart. People speak instead of American Protestants, American Catholics, American Jews, American Muslims, and American Buddhists—implying, at least as an ideal, that all faiths stand equal in the eyes of the law.

American politics resists anti-Semitism. In a two-party system where close elections are the rule, neither party can long afford to alienate any major bloc of voters—another reason why it is so critical that everyone take the time and trouble to actually vote. For the most part, the politics of hatred have been confined to nonvoters like African Americans, until they won the vote, or to nonvoting immigrants, or to noisy third parties like the anti-Catholic Know Nothings in the 19th century, or to single-issue fringe groups. America’s most successful politicians, now and in the past, have more commonly sought support from respectable elements across the political spectrum. Appeals to national unity, even in the era of Donald Trump, win more elections than appeals to narrow provincialism or to bigotry.

Of course, the fact that America has been “exceptional” in relation to Jews should not obscure the sad reality that there has always been anti-Semitism in America, as well as violence directed against other minority faiths. That history, as I read it, gives cause neither for undue celebration nor for undue alarm.

Jonathan D. Sarna is University Professor and Joseph H. & Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History at Brandeis University, where he directs the Schusterman Center for Israel Studies. He is the author of, among other titles,American Judaism: A History andWhen General Grant Expelled the Jews.