At Camp

An excerpt from Matti Friedman’s new book, ‘Spies of No Country: Secret Lives at the Birth of Israel’

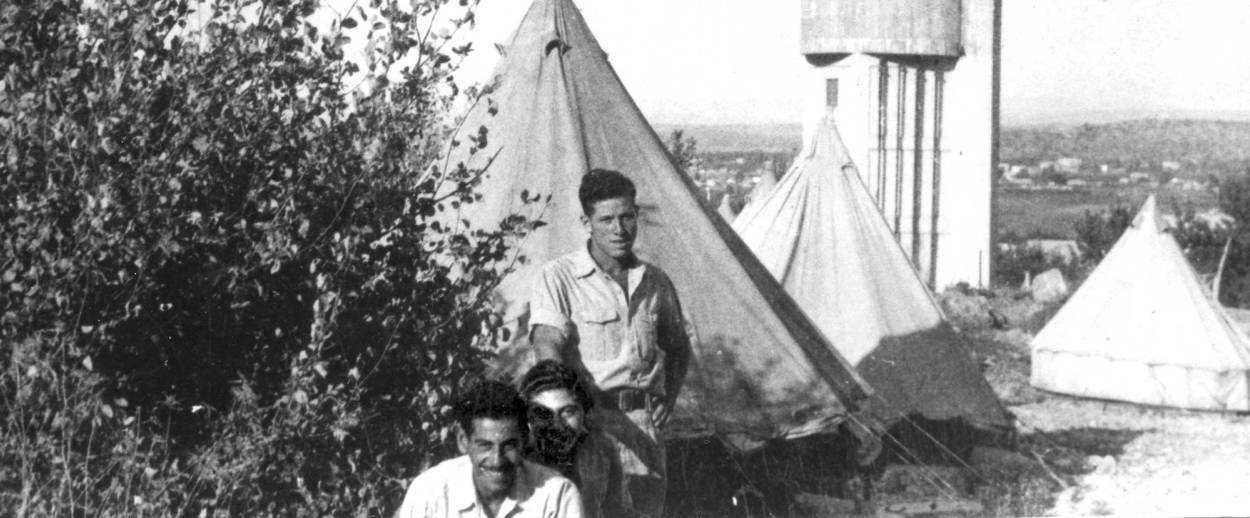

Having nearly been outed by an Arab observer who suspected he wasn’t really an Arab, then recognized by a Jew who knew he was a Jew, then nabbed by Jews who thought he was an Arab, the agent finally made it back to his friends. They were camped at a kibbutz on the formerly malarial flatlands of the coastal plain, a cluster of tents and sheds around a water tower. The Section moved around, but the camps looked more or less the same.

This was where they slept on mattresses they sometimes stuffed with corn husks, and where they kept the disguises purchased in the Jaffa flea markets: keffiyeh headdresses for villagers, work shirts or cheap franji suits, the kind worn by both Arabs and Jews, if they didn’t want to draw attention on either side of the line. The chances of a British raid against the Jewish underground were lower now that the pullout was close, but the weapons cache was concealed just in case.

Sam’an the teacher was there, with his English manners and his little Arabic library, and around him the lost boys he’d collected from slums, communal farms, and regular Palmach units, where they stood out among the Jews from eastern Europe because of the wrong skin shade and accent. Most of them didn’t have parents in the country, and some didn’t have parents at all. Their family was the Arab Section.

Isaac was there, and Yakuba, and Havakuk. With the newly returned Gamliel, these are our four. Three of them—all but Isaac— happened to share the same family name, Cohen, but it’s a common one among Jews, and they came not just from different families but from different countries. I’ve chosen to write about them because they were the agents who took part, individually or together, in the key events of the war; because they left the richest recollections and observations; and because each is compelling, and each in a different way. Havakuk, born in Yemen, was gentle—a quiet watcher. Isaac, the janitor’s son from Aleppo, had the muscles of a small boy who’d decided he wouldn’t be bullied, and the determination of someone who’d come a long way uphill. Yakuba, raised on the streets around the vegetable market in Jewish Jerusalem, was volatile and unusually brave. Gamliel was cautious and the most intellectually inclined, the only one who’d finished high school.

Among the other men at camp was David, nicknamed Dahud, who already had a wife, and who would soon have a daughter but would never meet her; and Ezra, who provided comic relief and was known for asking his comrades to train him to withstand torture by beating him. One story has Ezra squeezing his own testicles and screaming, “I won’t tell, I won’t tell!” They used to roll with laughter but wouldn’t have if they’d known his fate. There was a pair of younger trainees from Damascus, Rika the saboteur and his redheaded friend Bokai, both with roles to play later on, one heroic and one tragic.

Rika later described what it was like to arrive in this odd corner of the Jewish military underground:

An old gramophone turned out to be responsible for the noisy Arab tune that echoed around the place. It was balanced on a chair of doubtful stability. Two ill-dressed young men had positioned themselves on sloping ground, each on one side of a backgammon board, and fixed their eyes on the dice as they shouted the numbers. Hebrew and Arabic mixed in the air. A few “intellectuals” sat in a “quiet” corner reading an Arabic newspaper. … There was no doubt about it: we were in the camp of the Palmach’s Arab Section, that is, the “Black Section.”

The men sometimes called it that, the Black Section, because among the eastern European Jews who filled the ranks of the Palmach, and who made up most of the Jewish population in Palestine at the time, Jews from the Middle East were sometimes called blacks. The amount of humor in the unit’s name is hard to gauge from the present, but even back then someone seems to have had misgivings. The Hebrew word for “black,” shachor, was replaced with the nearly identical word shachar, meaning “dawn.”

That’s how the unit became officially known as the Dawn Section, or just The Dawn, the name that appears in many of the spies’ typed reports and, when they began moving beyond the border, in the log of coded radio traffic. But the unit was most often called the Arab Section, and that’s the name I’ll use.

Some surprise greeted Gamliel’s appearance at camp, because his letters from Beirut hadn’t arrived and they’d feared he’d been caught, that the number of dead had risen to four. The Section was already braced for it, and not just the Section: in those dark weeks at the beginning of the Independence War there was death in every unit of the Palmach and throughout the country, as the hopeful little world the Jews called the Land of Israel was strangled.*

Gamliel and the others had learned the trade in the quieter years before the war. They slipped in and out of Arab towns around Palestine, practiced dialect, saw what fooled people and what didn’t, and collected bits and pieces for the Hagana’s Information Service as the Jews prepared for the fight that their more insightful leaders knew was coming. The agents would sometimes bring back nuggets of military value, like a description of an armed rally in the town of Nablus and a quote from an Arab militia leader who addressed the crowd:

Independence is not given but taken by force, and we must prove to the world that we can achieve our independence with our own hands!

Sometimes it was impressions of Arab society or soundings of the mood, the kind of material sought by Mass Observation in Britain during the Second World War, when citizen-spies reported conversations and rumors to help gauge the direction of public opinion. A Section agent might deliver a summary of a sermon he’d heard at a village mosque during communal prayers on a Friday:

The sermon didn’t include a single sentence about politics. It was about giving charity and tithes to the poor from the yearly harvest.

Or a note on the popularity of the Egyptian movie musical The Adventures of Antar and Abla:

This movie has left a deep impression in their hearts, and songs from the movie are on everyone’s lips.

Or a snapshot from a strike called by Haifa’s Arab leadership against Jewish political aspirations in the summer of 1947, a few months before the Independence War broke out:

I saw a group of twenty or thirty kids, with six “leaders” about twenty-five or thirty years of age, walking around the neighborhood shouting, “Whoever opens his store is a pimp.” I walked for about an hour and a half, and every time a Jewish bus passed they smacked it with sticks. When it was some distance away they threw stones and broke a few windows. The leaders tried to prevent this vandalism. When the group reached the corner of Lucas Street and Mountain Way they saw an armored police vehicle and scattered in all directions.

Sometimes they came back with material that wasn’t intelligence at all. The teacher Sam’an took an interest in Arabic proverbs, for example, and told the men to collect as many as they could, rewarding a particularly good one with a bottle of soda or a morning off. This became a habit for Isaac, who published a few hundred of them in a little book many years later:

Esh-shab’an ma ya’ref shu fi bi-’alb el-ju’an

The sated man doesn’t know what’s in the heart of the hungry.

Lama bi’a el-jamal bi-yeketro es-sakakin

When the camel falls, the knives multiply.

This must all have seemed distant and frivolous by the time Gamliel made it back briefly in February 1948; ten weeks into the war, life at camp was unrecognizable. Demands for intelligence were coming from the beleaguered Jewish forces faster than the surviving men could handle. They were scrambling to grasp the direction of events, delivering reports like this one from Jaffa:

Private car no. 6544 is in the service of the [Arab] National Council. …

Pamphlets were given out to adults forbidding children under fifteen from going outside during the strike.

In the Manshiyeh neighborhood, families are leaving with their possessions.

In a conversation with an Arab man he expressed his opinion that violence is coming.

On Salameh Street at 19:00, there were twenty-five young men in khaki divided into five teams of five.

Between those terse lines it’s possible to picture one of the men sitting at a cheap café or smoking on the steps of the post office, looking around, asking a question of a passerby as casually as possible: What do you think—will there be more blood?

Gamliel didn’t linger at camp after his return, and he soon disappeared again for good. The remaining men seem not to have paid their comrade much thought once he was gone. It would be a few months before Beirut became the center of the action, and it’s not clear they even knew he was there; the unit was too disorganized for real compartmentalization, but you were supposed to keep your missions and alias to yourself. Events inside Palestine were grave and deteriorating, and the rest of the Arab Section had more urgent concerns. The 1948 war was not a chess game. But if we picture it that way for a moment, then Gamliel was a bishop moved to one corner of the board in the hope that he’d be useful later on.

* Like most characters in this story, the country in question has multiple names. Palestine was the one used by the British during their rule from 1917 to 1948. Some Arab residents used the same name—Filastin in Arabic—though many rejected the borders imposed by Western powers and saw themselves as part of a greater Arab or Muslim entity. The Jews knew the country as the Land of Israel, or simply the Land. The term “Palestinians” for the Arabs of Palestine came into use only later, like the term “Israelis,” and here I’ll refer to everyone the way they referred to themselves at the time—as Arabs and Jews.

From the book Spies of No Country. Used with permission of the publisher, Algonquin Books. Copyright © 2019 Matti Friedman.

Matti Friedman is a Tablet columnist and the author, most recently, of Who by Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai.