The Mystery of Baruch Goldstein

Twenty-five years after he massacred 29 Palestinians midprayer, the killer is more revered than ever. Why?

At 5:05 a.m. on the morning of Purim, Feb. 25, 1994, the phone rang in the regional command center of the Israel Defense Forces in Kiryat Arba, on the outskirts of Hebron. Shlomo Edelstein, the officer in charge, picked up the phone and was surprised to hear the voice of a local doctor he knew well.

“He told me to send a jeep within five minutes to the infirmary,” Edelstein recalled, “which seemed really strange to me, because he wasn’t the doctor on call. And even if someone called him directly at home, say, why would he ask for the jeep? If it was a real emergency, wouldn’t he need an ambulance?”

Still, the doctor was decisive, so Edelstein called Motti Unger, who drove the community’s emergency vehicle, and asked him to swing by and see what was up. When Unger arrived at the clinic, the doctor was waiting outside. He just needed a quick ride, he said, to the nearby Cave of the Patriarchs, slightly more than a mile away. The ride lasted about seven minutes, not long enough for Unger to ask any questions. Anyway, the doctor did all the talking: He gave Unger his car keys and asked him to drop them off later with his wife.

Unger didn’t find it too strange that the doctor was wearing army fatigues, or that he was carrying his Galil automatic rifle. Hebron was a violent place, and attacks on the region’s Jewish residents were getting more and more common. The army needed a medic on hand, which meant that the doctor was frequently on reserve duty, rushing from one bloody scene to the next, doing his best to save lives. He was so dedicated to his duty that he’d won a citation from the army a few months earlier, and had earned himself a promotion to major and the admiration of his peers and commanding officers. If he needed a quick early morning ride, he probably had his reasons.

The soldiers guarding the cave were just as incurious. One of them asked the doctor why he was there so early, and in uniform no less. The doctor smiled and mumbled something about miluim, Hebrew for reserve duty, and walked in. The small Abraham Hall, underneath which the first patriarch is believed to be buried, was nearly empty, with 13 Jews preparing for the morning prayers. The doctor walked over to the green metal door that connected the room to the much larger Isaac Hall, at the end of which, according to legend, lies the locked door that leads directly to Gan Eden, the Garden of Eden. Normally, the door would’ve been guarded: Just the evening before, a few Palestinians, concluding their evening prayers, crossed over to the Jewish side, tore a few of the books, and sprinkled thumbtacks to injure the feet of Jewish worshippers. But it was too early, the soldiers thought, to worry about such petty scuffles, too early for anyone to do anything truly bad. The doctor unbolted the door and walked in.

He took a few steps along the wall in the marvelous room with the high, arched ceilings and the ornate rugs. He was staring at the backs of 800 Muslims, all kneeling in prayer. And then, he took out his rifle and started shooting.

When security forces finally made their way to the scene, they found the rugs soaked in blood and littered with more than 100 casings. They found the bodies of 29 Muslim men, murdered as they prayed peacefully. And in one corner, lying perfectly still, his head bludgeoned by a fire extinguisher wielded by a few of the men who rushed to stop the attack, his black kippah by his side soaked in blood and gray matter, was the doctor, Baruch Goldstein.

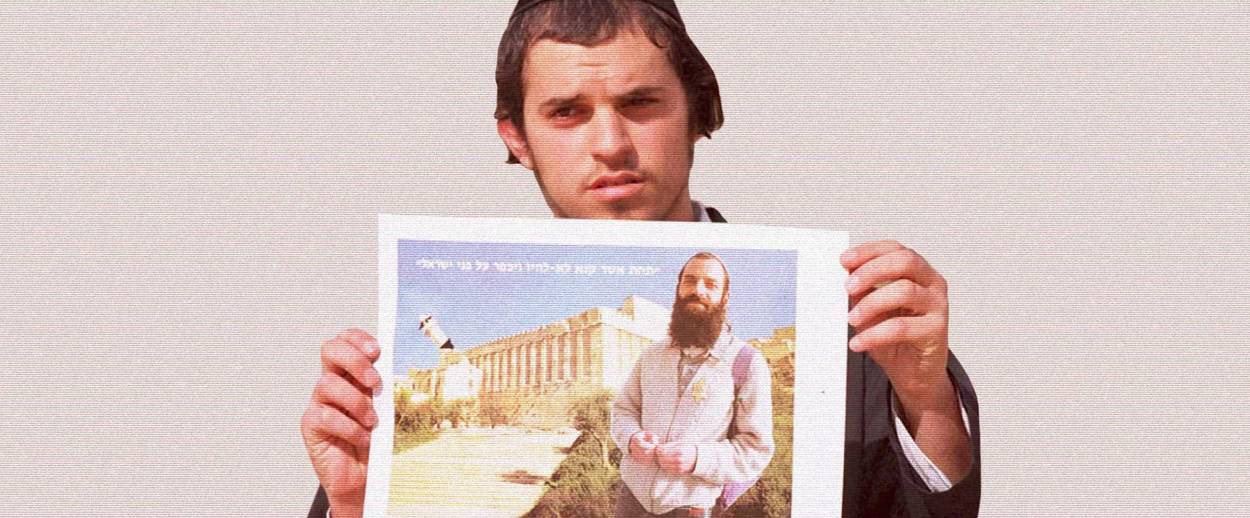

In the immediate aftermath of the attack, Israelis of all stripes rushed to denounce Goldstein as a crazed lone wolf and condemn his actions in the strongest possible terms. But in the 25 years since the massacre, Goldstein has enjoyed a strange and thoroughly unexpected afterlife. His gravesite, in a local park—the army refused to allow Goldstein’s family to bury him in the communal cemetery, wishing to deter potential pilgrims from praying at his tomb—draws throngs of admirers nonetheless, some of whom erected an unauthorized mausoleum of sorts to their hero. Many more named their children Baruch, and some, like Itamar Ben-Gvir, who is currently running for the Knesset with the far-right Otzma Yehudit party, have his portrait hanging on their living room walls.

Why this adoration? Israeli culture at large isn’t big on hero worship, and even if it was, Goldstein would still be a mind-boggling choice. Even those who don’t seem to mind the gruesome nature of his crime—and, thankfully, very few had chosen to follow his path into violence—concede that the 1994 massacre was nothing more than a flash in the sizzling pan of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Unlike Yigal Amir, who assassinated Rabin and thereby changed the course of Israeli history, Goldstein achieved little that was long lasting. His was an orgiastic outburst of vicious bloodletting, leading nowhere. Why, then, has he emerged as a patron saint to a growing community of Israelis? And what might his continuing ascent mean for the country at large?

To answer these questions, it’s best to begin at the beginning, on Friday, January 22, 1982, the date of Goldstein’s first known publication. Rarely revisited since, the essay, an opinion piece published in the Jewish Press, is instrumental in understanding the chief conundrum that was to guide Goldstein life. Fresh out of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and an alum of Yeshiva University, the young physician had little patience for his alma mater’s famous motto, Torah UMadda, Torah and science, embodying the tension between the religious and secular worlds. For Goldstein, there was only room for one guiding light; he named his article “’Democracy’ and Halacha.”

Observing “how desperately the 20th century, Hellenized Jew attempts to reconcile the Judaism he has inherited with the foreign culture he has adopted,” Goldstein then accused said Hellenized Jews—basically all who do not stringently observe the Torah’s commandments—of failing in this task precisely. “’Democracy,’” he wrote, seemingly unable to print the word unless in scare quotes, “is a concept dating back to the Greeks, a people who came upon the world scene centuries after the Jews. While democracy represents the major legacy of the Greeks, Torah and Halacha are the G-d given inheritance of the Jewish people. Often, the twain do not meet.”

Very few people spoke like that at the time, particularly in Israel, where Goldstein moved by year’s end. If you looked at the Jewish universe, you saw, roughly speaking, three distinct camps, divided mainly by the question of how to think about the Jewish state. For secular Zionists, the state was Judaism’s embodiment, its endgame; Israel’s miraculous triumph in war after war was proof of its otherworldly status. For this group, which included the lion’s share of Israelis, no further manifestations of piety were required to live Jewishly; service in the IDF was sufficient. The Haredis, on the other hand, rejected the state altogether, adhering instead to traditional Orthodox practices, while the third camp, the religious Zionists, believed that the state was part of the divine plan to usher in the messianic age and participated enthusiastically in its institutions, the army first and foremost. Goldstein believed in a fourth and radical option: Like his teacher, Rabbi Meir Kahane, his Zionism was, in the astute observation of Shaul Magid, “a strange mix of the secular and the religious” which believed that Jews enjoyed a Divine right to their Promised Land but that to claim it, forceful action on the ground was a must.

With such a stringent set of beliefs, Goldstein was on a collision course with Israeli society almost from the moment he arrived. On the one hand, he was, by all accounts of those who knew him, a kind and gentle-mannered man who rarely raised his voice above a whisper. After his death, friends and neighbors told whoever was willing to listen stories of the Baruch they knew: How he took two or three hours once or twice a week to meet with Nachum, a mentally disabled boy, and study Torah with him; how, in the cold Hebron winters, he always rubbed his hands together before examining a young patient, just to make sure they were warm and nice to the touch; how, far from irate, he would thank each patient who called him after hours at home for the opportunity to do a mitzvah and heal a Jew in pain. But the same delicate man also affixed a yellow Jewish star with the word “Jude” to his shirt after the Oslo Accords were signed, said repeatedly that the Arabs were simply latter-day Nazis, and took to demonstrating frequently and publicly against any negotiations with Israel’s enemies. That, in his worldview, was a betrayal of both God and man, the former having chosen the Jews as His kingdom of priests and the latter having the responsibility of living up to the divine task. Goldstein’s rhetoric grew so heated that, visiting Kiryat Arba just nine days before the massacre, a documentary filmmaker asked him how he reconciled his dedicated service as a lifesaving physician with his calls for violence against the Arabs. Quoting Ecclesiastes, Goldstein said dryly: “A time to kill, and a time to heal.”

Before the massacre, such pronouncements, jarring as they may sound, came off as radical rhetoric, the extreme right opposition standing athwart history and yelling stop. On Purim of 1994, however, all that changed. By opening fire in the Isaac Hall, Goldstein gave his supporters something greater than the primitive catharsis some people take in seeing their enemies slaughtered; as would soon become clear, what Goldstein delivered that day was something akin to a revelation.

What precisely was the nature of this religious awakening became clear a few months after the shooting, with the publication of a slim volume titled Baruch Hagever. The title is taken from Jeremiah 17:7—“blessed is the man that trusteth in the Lord, and whose hope the Lord is”—but it’s also a Hebrew pun suggesting that Baruch, Doctor Goldstein, is a gever, a man’s man. At the heart of the collection is an essay by the influential rabbi and scholar of mysticism, Yitzchak Ginsburgh. Whenever it is mentioned in the Israeli media, which is often—and almost always by people who hadn’t bothered reading it—the essay is portrayed as a hateful screed calling for violence against the Arabs. In reality, however, it is something eminently more complex, a radical interpretation of Goldstein’s massacre as a paragon of religious ecstasy.

The essay is written in the traditional style of Musar, the ascetic 19th-century Eastern European movement urging religious Jews to worship God with greater care and passion. In an insightful analysis published in the Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Don Seeman, assistant professor of religion and Jewish studies at Emory University, noted the similarities between Baruch Hagever and Mesillat Yesharim, Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzato’s masterpiece of Jewish ethics which is considered one of the seminal texts of Musar. Like Luzzato, Seeman observed, Ginsburgh placed an emphasis on the importance of “undertaking action for the sake of divine honor with no thought to personal pleasure.” But while Luzzato bound his believers in the traditional, cerebral, and legalistic shackles of Halacha, Ginsburgh called for an “ecstasy of holiness [that] beats primarily in the heart.” Like the German Romantics—primarily Heinrich von Kleist—who argued that whichever action was spurred by man’s reflexive nature is truest and best, Ginsburgh, in an intricately argued and wildly innovative analysis of Jewish mysticism, wrote in Baruch Hagever that “sanctifying the Lord’s name is a deeply personal matter, a trembling of the deepest ‘place’ in a Jew’s soul,” and that this act of sanctification was both subjective, spontaneous, and the domain not of the brain but of the heart.

And the heart, Ginsburgh continued, sometimes craves revenge, an entirely natural sentiment. “Being and the will to being are the foundation of natural life in the world,” he wrote, “and vengeance is therefore a kind of natural law. One who takes vengeance thereby joins the ‘ecological stream’ of being; his true being and that of the world meet.” By sacrificing himself for God’s glory, by connecting with his “ecological stream” and dedicating his life to vengeance, Goldstein, Ginsburgh argued, achieved a sort of transcendent state that was all the more impressive for the impact it had, both on the gentiles who feared it and on the Jews, or at least some of them, who cheered for it. Returning to his key operative word, “spontaneous,” Ginsburgh wrote that “we should examine what was the spontaneous reaction of the majority of the people of Israel, what the ‘simple Jew’ within each one of us felt, and even though not all were consciously sharing in admiration, most were aflutter with a memory instructing them that the name of Israel is a wondrous, dear, and surprisingly vital thing.” Put simply, too long burdened by the muddled demands of the intellect, the soul yearns for some way to connect with God, and finds it in the aftershock of Goldstein’s radical act.

The rest of Ginsburgh’s essay is just as intricate, advancing a host of other arguments, including one, favored by Goldstein’s defenders, that the shooting was a preventive measure designed to stop a Palestinian terror attack the Jewish residents of Hebron had received warning was imminent (because the findings of the subsequent committee that investigated the massacre are still largely classified, it’s difficult to corroborate or refute this claim). And it ends with Ginsburgh stating that it is not his intention to deliver a definitive halachic ruling on Goldstein’s actions, as well as acknowledging the point of view that sees the shooting as an inexcusable and vile murder of innocents that, if anything, desecrates God’s name. But by placing the shooting in a theological context, Ginsburgh wrote the companion piece to Goldstein’s own 1982 essay: Just as Halacha and democracy were incompatible, so were the head and the heart, and anyone wishing to reclaim the Jewish state and take action to transform it into the divine vessel it was always meant to be had to learn how to unleash the fury of feeling, by any means necessary.

It was just the sort of theological license some on the Israeli right were craving. With the Oslo Accords a fait accompli even after years of right-wing governments, any attempt to reason with the state seemed futile. If even a decade of Bibi Netanyahu brought nothing more than ongoing negotiations with the Palestinians, however forestalled; subservience to the courts, even when their rulings contradict Jewish law; and a culture dominated by increasingly progressive, cosmopolitan values, maybe, went the logic, it was time to radically break up with democracy. And no one embodied this putative split better than Goldstein, Baruch the man, the only one, as his admirers often remind anyone who would listen, who was man enough to stand up and do something.

But who would listen? Not the Israeli mainstream: As ascendant and present as Goldstein is among the hard right, he is largely ignored, if not reviled, by the rest of the country, and when he’s not he’s often painted as a monstrous lunatic whose actions are beyond reason. A few years ago, a popular satire show on Israeli TV spoofed Eminem’s song “Stan,” about an obsessive fan driven to violence after the rapper ignores his admiring letters; in the new version, Goldstein was the jilted fan, opting for mass murder out of frustration with God’s ongoing silence. It was a version of Goldstein that most Israelis embraced, the killer as caricature. But Goldstein’s ideas are just as terrifying to the Israeli mainstream as his actions; anyone who took the time to read Goldstein’s work or Ginsburgh’s theology would see that they spell the end of the balance most Israelis consider most sacred, the balance between being a Jewish state and a democratic state. This equilibrium, they suggest—one in action, one in thought—was always a fantasy, and now the time has come to switch loyalties, to follow the heart, to make the state Jewish again, as it had been back in the days of the Bible.

To secular ears, this may sound like a disaster. Among some in the religious community, it’s gaining traction. Tomer Persico, for example, one of the more astute scholars of Jewish New Age practices and spirituality, has noted that the Goldstein/Ginsburgh idea is precisely the engine driving the Hilltop Youth, renegade young Jews who live largely in makeshift outposts in Judea and Samaria and who frequently clash with both Israeli law enforcement and their Palestinian neighbors. Their violence, Persico observed, isn’t incidental—it’s part of their romantic ethos, a religious practice similar to Goldstein’s massacre in sentiment if not in scope and designed to stir their souls and bring them closer to God. And, like Ginsburgh, they, too, see these actions in ecological terms. Perisco quoted a 17-year-old Hilltop Youth as saying, “being in touch with nature has allowed me to mature. My friends, who study in traditional educational institutions, they’re glued to their chair, their desk, or the internet. They don’t know what nature is … I think my outlook has allowed me to discover God from a deeper place.”

You hardly have to be a theologian to understand the appeal of this idea. As secular society grows more complicated, more compromised, and more challenging, young people are bound to look elsewhere for ecstatic alternatives, especially if they were raised in an environment, like religious Zionism, that was always informed by messianic yearnings. If the state fails to bring about redemption, as religious Zionism’s founding fathers had hoped, it’s understandable why so many would decide to roll up their sleeves and try to hasten it themselves. This is why, when asked about Goldstein shortly after the massacre, Yeshayahu Leibowitz, the celebrated Israeli philosopher who, as an Orthodox Jew, gained notoriety with some for calling the conduct of Israeli soldiers toward Palestinians “Judeo-Nazi,” said he believed the shooter was far from a marginal figure. “Baruch Goldstein,” Leibowitz claimed, “is an authentic representative of large swaths of the Jewish people.”

Leibowitz’s warning was mainly ignored at the time, especially as it suggests, when read at face value, that large swaths of the Jewish people are, at least potentially, homicidal maniacs. But Leibowitz’s meaning was different, deeper, and, again, far more terrifying: Many Jews are like Goldstein, he believed, in that they gradually came to see democracy as incompatible with their faith, and, when forced to choose, would choose Judaism, following religious edicts even if they commanded actions that modern, Western republics considered absolutely anathema.

None of this is to say that all, or even most, of the men and women who decorate their homes with photographs of Goldstein or who vote for the party populated by his friends and disciples are dreaming about a strict theocracy. But politics, like nature, abhors a vacuum, and when the secular and religious right alike failed, despite a decade in power, to bring about sufficient change to the status quo, many started looking for an alternative. And many, sadly, found it in an ideology that weds together the natural and the divine, spontaneous impulses and godly decrees, violence and catharsis, Jewish pride and the promise of a simpler, purer future, an ideology that began life 25 years ago on a cold early morning in Hebron with the sound of a gun going off.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.