When ‘Finance’ Becomes a Code Word for Jewish

The idea that there’s something wrong—and Jewish—about finance has a long, ugly history that’s been making a comeback and distracting from necessary reforms of the financial industry

In July, Elizabeth Warren published a nuanced overview of the mechanics of private equity firms and how to better regulate them. It may sound dry but as a millennial who graduated out of college into the Great Recession without a large safety net, I felt a strong personal stake reading Warren describe the consequences of our current lax rules on private equity and detail suggestions for more responsible regulation. Warren, who has been eating away at Joe Biden’s lead in the polls for months and steadily making gains toward becoming the front-runner in the Democratic primary, has a background as a legal scholar who specialized in debt and credit. Starting long before she entered politics, Warren has devoted her career to fighting the disastrous regime of deregulation, tax cuts, and upward wealth redistribution that began in the 1980s, a background that makes her seem like an ideal candidate to fix the systemic issues in our economy that have caused the collapse of the middle class. Yet, one line in her article gave me pause:

“But far too often, the private equity firms are like vampires—bleeding the company dry and walking away enriched even as the company succumbs.”

Here, even Warren supporters such as myself should pause at what comes dangerously close to a sinister, conspiratorial trope. Language that compares bankers to parasites has long been a staple of anti-Semitic scapegoating and a way for demagogues to rile up their base. Warren shows no evidence of being either a demagogue or an anti-Semite, but she does seem to be a party to the left’s growing reliance on outrage in their search for a bogeyman in the financial elites—a search that invariably appeals to conspiracy theorists and anti-Semites. Warren and others on the left should be applauded for their necessary critiques of the financial industry and bringing attention to dangerous policies like the deregulation of risky investment vehicles. But it’s necessary to step back and examine the roots of the left’s contempt for finance when that contempt extends beyond the specifics of policy and to the nature of the financial industry itself. The idea that finance is “vampiric,” that it feeds off of the honest productivity of hard workers to extract unmerited earnings, is a sentiment that has direct roots in a long history of anti-Semitism.

The idea that money derived from finance is parasitic because it is not from “productive” labor was developed by medieval Christian natural law theology but has even older origins in the work of Aristotle. In Aristotle’s Politics, he divides wealth into two categories: natural and unnatural. Wealth is natural when it derives from productive pursuits, defined as the fruits of physical labor like agriculture and craftsmanship. By contrast, Aristotle condemns what he calls unnatural wealth that is produced not from making things, but from trade and exchange.

While Aristotle is scornful of commerce, the brunt of his contempt is reserved for usury, the lending of money at interest: “The most hated sort, and with the greatest reason, is usury, which makes again out of money itself, and not from the natural object of it.” Simply, that which is natural is good and productive and that which is unnatural is bad and parasitic. Here, in Aristotle’s philosophy of naturalism, is the philosophical foundation for the Western world’s distrust of moneylending, which has survived in recognizable form to this day

The Aristotelian condemnation of usury outlived ancient Greek society and flourished across medieval Europe and the Middle East. In Europe, philosophers known as the Scholastics, the most famous of whom was Sir Thomas Aquinas, elaborated extensively on the Aristotelian concept of nature, developing it into a form of Christian ethics known as natural law theology. At its core, natural law posits that there is an intrinsic order and morality in the world ordained by God and discoverable through Christian theological inquiry. Natural law theologians wrote polemics against moneylending, continuing Aristotle’s idea that only crafts, agriculture, and inheritable title are the pillars of a moral economy, while moneylending is parasitic, extracting wealth from those involved in productive pursuits. As a result, the Vatican and many monarchies of medieval Europe outlawed usury. The ban on moneylending did not, however, stop people from needing to borrow money. Only Jews, whose souls were already considered lost, were allowed to lend money. Digging beneath the surface, the historian Jerry Muller, in his book Capitalism and the Jews, found a powerful hidden incentive in the laws governing the role of Jews as lenders. Kings could not tax the nobility, but nobility could borrow money at interest from Jews, and kings could heavily tax the Jews. Jewish moneylending thus became a de facto means of taxing the nobility, with kings retaining most of the profits that Jews made from lending money to the nobility.

Not only were Jews the designated moneylenders of medieval Europe, many regions of Europe explicitly banned Jewish land ownership and craftsmanship. Such bans were prominent in Western and Central Europe, particularly from around the end of the First Crusade until the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when Napoleon extended citizenship to Jews in France. In many areas of Europe, including regions of modern-day France, Germany, Italy, and others, the Jewish populations were confined to living in ghettos, segregated Jewish quarters in urban areas, and were barred from living on arable land. While Jews were at times permitted to practice certain crafts, they were largely excluded from the powerful crafts guilds. In many instances, the ban on Jews learning manual skills extended so far that Jews could not even be their own carpenters and architects. For example, the 16th- and 17th-century Jews of the Venice ghetto had to hire Venetian Christian architects to build their synagogues. Thus, Jews were prevented from engaging in what natural law adherents called productive labor and then castigated and penalized for not participating in such fields. Confined only to hated professions, Jews were then hated for practicing those professions.

Confined only to hated professions, Jews were then hated for practicing those professions.

It was only with the Enlightenment and the subsequent period of industrialization that European prejudices began to break as leading philosophers rejected the prohibitions against finance that so thoroughly permeated the medieval world. As Muller notes, Montesquieu wrote in 1748 that, “We owe all the misfortunes that accompanied the destruction of commerce to the speculation of schoolmen.” In other words, Montesquieu argued, summing up a position shared by other Enlightenment philosophers, European economic development had been stunted for centuries due to the philosophizing of theologians. Most famously, Adam Smith in his Wealth of Nations extolled the virtue of accumulating wealth not solely through craft and agriculture, but through fostering economies of scale—a process that requires financial institutions. Smith even supported lending money at capped interest rates to qualified borrowers.

But the pro-finance sentiments of Smith and Montesquieu did not go unchallenged as the large scale economic shifts and rampant inequality of 19th-century industrialization led many philosophers to double down on the medieval contempt for finance—most notably Karl Marx. While the political radicals of the 19th century did not explicitly extol natural law theology, and were often committed atheists, they nevertheless betrayed its influence in their emotionally charged distinction between productive and parasitic labor, and the particular vitriol they showed toward both finance and Jews.

In his infamous essay, “On the Jewish Question,” Marx wrote: “The Jew has emancipated himself in a Jewish manner … because money has become a world power. … The Jews have emancipated themselves insofar as the Christians have become Jews.” That is, in so far as Jewish people had found social or political acceptance, it was only because the world had become more perverse. The world was becoming one in which finance was less and less considered an unmentionable occupation for designated outcasts, than a standard, accepted profession. Finance was still a long way from the prestige that it would gain in the 20th century, but its growing normalization kindled fear and anger, much of which was directed into a growing body of anti-Semitic conspiracies. People whose lives were destabilized and impoverished by unscrupulous labor practices and unregulated technological change could pin their hardships on the twinned evils of finance and the Jews. For anti-Semites of both the left and right—and in the 19th century there were still powerful strains of right-wing anti-capitalism—the political emancipation of Jews was thus the result of turning the world “Jewish”; the Jews freedom purchased through the immiseration of others. The template created by Marx and other 19th-century thinkers who connected their opposition to finance and capitalism with the purported “Jewishness” of those practices would proliferate in subsequent decades, taking root in cultures outside Europe, as financial capitalism also spread across the globe.

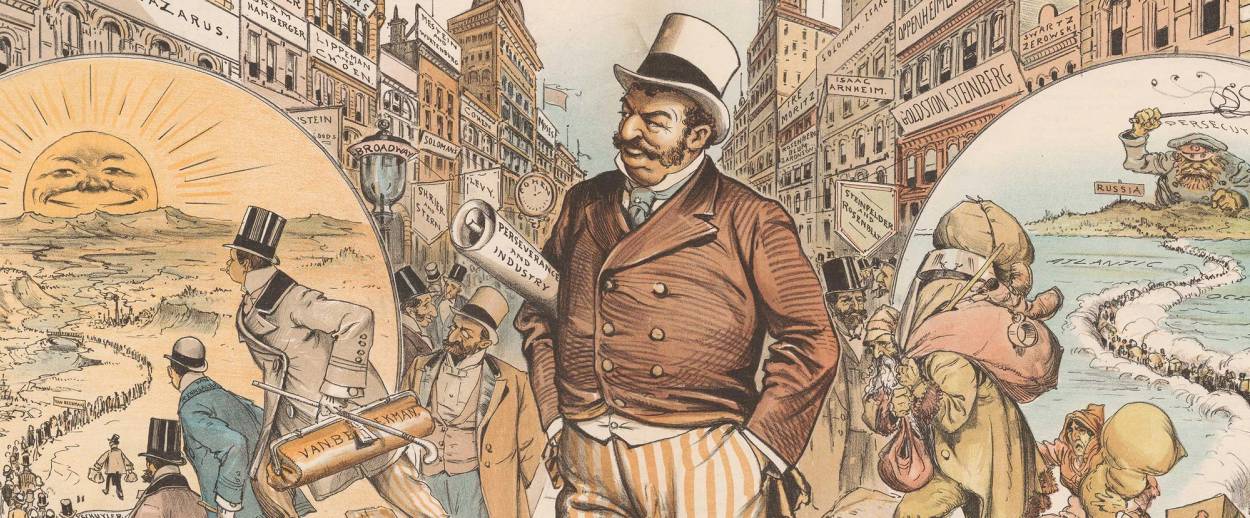

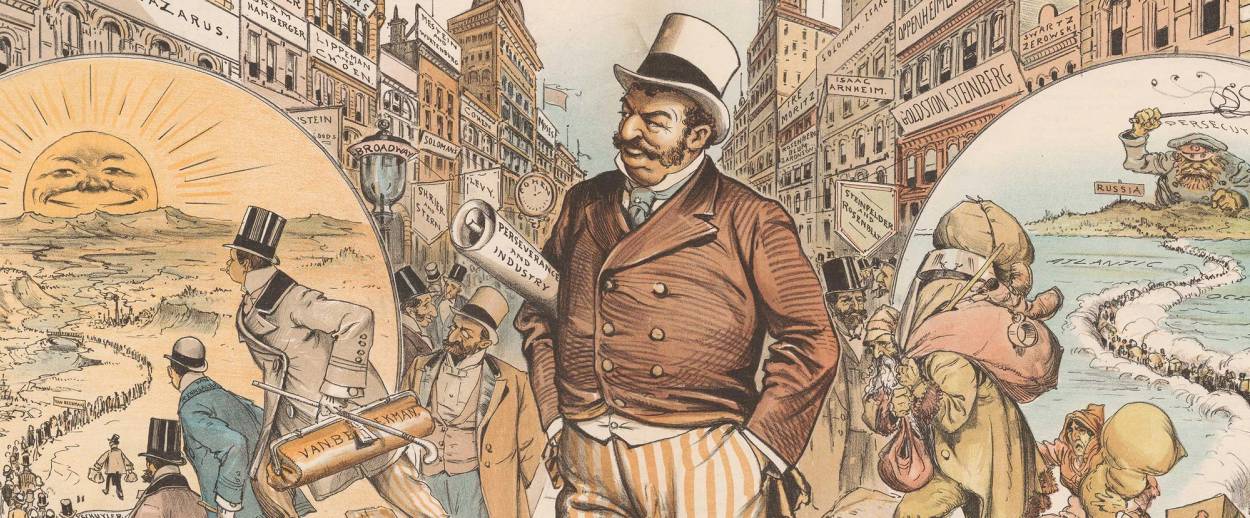

Throughout American history, key figures and political movements have divided the U.S. between two classes of people: rural farmers who support a decentralized government, and urbanites working in commercial and financial professions who favor a stronger national government. The hardworking lone agriculturalist known as the “yeoman farmer” has been an esteemed cultural figure since the days of Thomas Jefferson. Likewise, the Hamiltonian supporters of strong government and administrative professions are often cast as the “evil bankers in New York,” smeared in populist rhetoric as villainous manipulators of land and currency, corrupting a pure way of life and preventing “honest, hardworking” folks from making a living. The trope that there are essentially two forms of professions: honest ones that cause a person to break a sweat, and dishonest ones that exploit true labor, has not only survived since Aristotle, but remains a powerful force in popular culture and political thought, animating deep resentments while obscuring the more complicated, and less starkly moral, nature of work and economic production.

In fact, pitting finance against agriculture and craftsmanship obscures the mutually beneficial potential of the two sectors. Commodities trading, for example had its start in ensuring money to farmers even before knowing their crop yield, encouraging farmers to continue to grow staples and protecting them against going bankrupt due to a bad season. Finance, when subject to smart and good-faith regulation, is ultimately a way to raise funds and spread risk so that people can start or expand businesses, or continue working in a necessary field despite uncertainty. Finance in itself should not be conflated with the particularly American political propensity for dismantling regulatory laws that rose to prominence in the 1980s but has existed in various forms in our nation’s history.

There is a cyclical nature to the political movements emphasizing the division of “productive” from “parasitic” labor. Not surprisingly, they are strongest in periods of economic turmoil. For more than a century during America’s economic downturns, populist political leaders have rallied people by expounding on the Jeffersonian motif of an idealized, self-sustaining pastoral way of life that has been sabotaged by the bankers in New York tinkering with the economy. Certainly, not all populism is bad, and indeed, most populist movements have brought to light the reality of economic insecurity and exploitation. But populist vitriol about finance can walk hand in hand with anti-Semitism. William Jenning Bryan’s 1897 “Cross of Gold” speech is a classic of 19th-century American populism, yet historian Richard Hofstadter notes in his Age of Reform that perhaps nothing did more to reinvigorate American anti-Semitism than the frequent allegations that the “Shylocks” and “Rothschilds” controlled the banks that controlled the farms.

In the 1930s, during the Great Depression, populist challengers to Franklin Delano Roosevelt often fostered anti-Semitism while they campaigned against finance. Huey Long, governor of Louisiana and senator who ran as a third-party populist candidate to the left of FDR, inveighed against the millionaire classes and the bankers. While Long himself did not use overtly anti-Semitic rhetoric, he hired the virulent anti-Semite Gerald L.K. Smith to organize one of his popular campaign programs. Meanwhile, Father Charles Coughlin, a populist radio show host with a large following, routinely lumped Jews in together with communists and bankers as agents responsible for the Depression, reprinting The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in his own periodicals.

It is precisely this history that makes it incumbent on opponents of economic inequality, like myself, to pause and consider our language. Certainly, an economy that has been deregulated to the point that businesses put shareholder profit above raising their employees’ wages, or an economy that does not collect enough revenue to support government services, does not deserve support. The issues to care the most about are our nation’s shortage of stable, well-paying jobs, our difficulty providing basic programs to our citizens, and an underlying national ethos that makes many Americans believe that those suffering “deserve it.” The greater issue facing the U.S. is not anything intrinsic to the nature of finance, but the overfinancialization of our economy—the rampant deregulation of financial products coupled with the primacy our businesses give to shareholders and incentives to do so that Congress has written into our tax code for the past several decades. But as a Jew, I am aware of the dangers in conflating a call for structural reforms of our government and economy with the moral demonization of the financial industry’s intrinsic nature.

Undoubtedly, smart candidates with detailed policy plans like Elizabeth Warren are in a hard place: Their very precision and breadth of knowledge can alienate voters. Politicians who shy away from the politics of outrage can lack the emotional magnetism of a candidate like Bernie Sanders or Donald Trump, whose anger over injustices, real or perceived, is felt by voters as much-needed empathy. But we must be wary of the populist style of paranoid political outrage because too often riling up a hatred of the “elites,” deployed as an emotional charge rather than a specific critique, leads to the demonization of Jews. Elizabeth Warren has long been the candidate of nuance, which is why I admire her; and I hope that she and others will continue to make the legitimate disagreements with economic policy that are not only impassioned but humane, and lead to better outcomes for all Americans instead of offering up scapegoats.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Elyse Wien has a masters in American history from the University of California, Santa Barbara, with a focus on labor and economic policy. She received her B.A. from Cornell University and is currently a J.D. candidate at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law.