Did a Supposedly Nazi Document Fool the Experts?

A cautionary lesson in how the ‘SS Rentabilitatsberechnung,’ a dramatic document of unknown provenance, entered the conventional wisdom about the Holocaust and may have provided ammunition to deniers

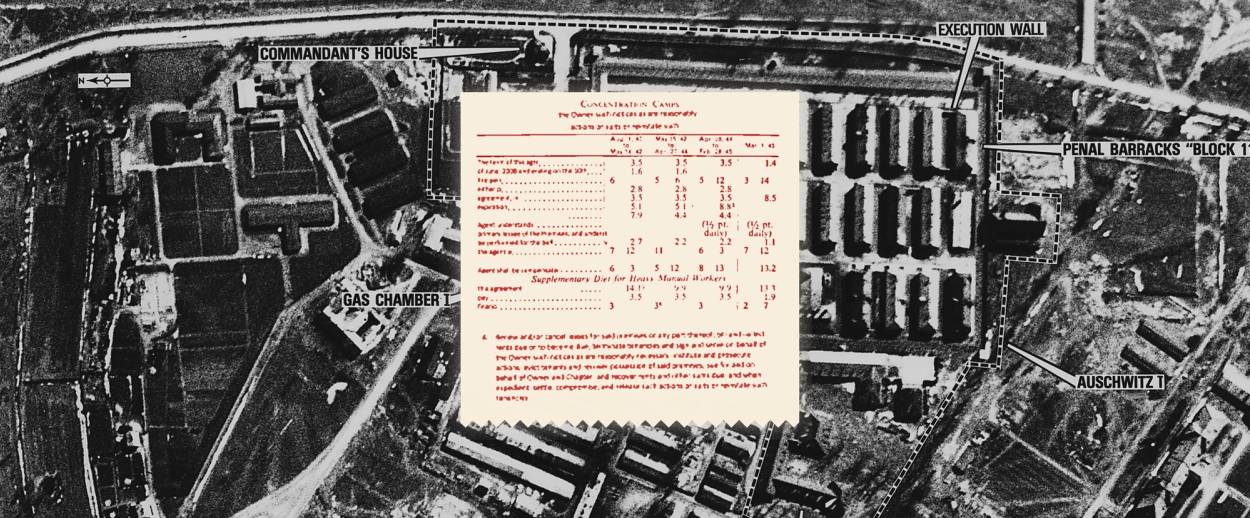

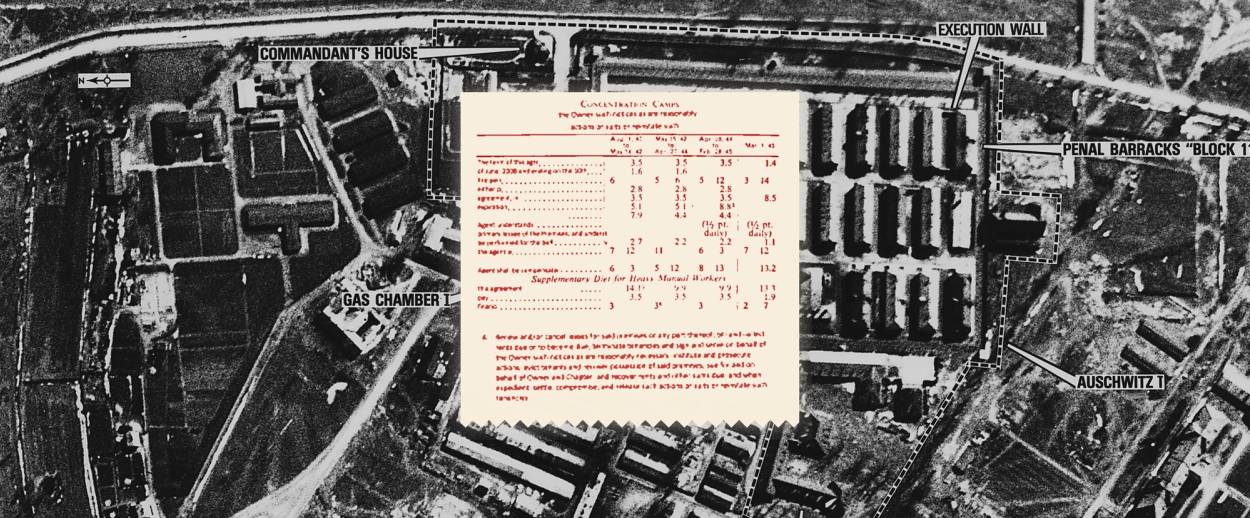

For the last 60 years, an obscure document called the SS Rentabilitatsberechnung that purports to calculate the profit generated by the Nazi’s slave labor killing machine has been quoted by historians, writers and rabbis, exhibited at museums, and used in classrooms around the world.

The problem is that it appears to be, if not an outright fabrication, then at the very least an artifact of unprovable provenance. This would be a problem in any historical field but is especially troubling in the high stakes world of Holocaust history where even routine matters of historical revision provide fodder to Holocaust deniers

The SS Rentabilitatsberechnung, which roughly translates as “profitability calculation,” has been widely cited as a source that shows how much profit the SS expected to realize from the average slave laborer. It’s been in circulation for decades and until very recently was referenced in the audio guide of the acclaimed exhibit Auschwitz, Not Long Ago, Not Far Away at The Museum of Jewish Heritage—A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, in New York.

More than 135,000 visitors have attended the exhibit since it opened last May. Museum officials estimate about 70% of the visitors rely on a 90-minute audio and video program to guide them through the exhibit’s three floors of somber artifacts, documents, and presentations.

Earlier this month the exhibit’s curators quietly deleted a stunning charge about the Nazi forced labor program from the audio guide. The deletion amounted to a single, 13-second sentence from the 90-minute guide: “During World War II, the SS calculated that, after costs such as cremation, but not including the value of bones used in fertilizer, the profit made from each prisoner was roughly $745.” But the expunged reference to the profitability calculation was dramatic enough to have been picked up and paraphrased by The New York Times in its in its May 8 review of the exhibit.

The episode provides a cautionary lesson in how a dramatic document of problematic provenance insinuated itself into the conventional wisdom about the Holocaust—and may have inadvertently provided ammunition to deniers.

I first received a poor copy of a copy of the SS document more than 12 years ago from an octogenarian survivor. He said he had gotten it from the widow of a rabbi who had found it in her late husband’s files. “It’s shocking, unless you were there and saw it.”

Indeed it is.

It lists “daily average rental income” of RM 6, the price the SS charged private companies for a skilled worker. Subtracting 70 pfennigs for food and overhead leaves a gross profit of RM 5.30 per day.

This sum is multiplied by 270 days—nine months—the average life expectancy of a forced laborer. This yielded RM 1,431.

Add another RM 200 from “Proceeds per rational value of corpses”—gold teeth, clothing, items of value, and money. After deducting RM 2 for cremation but noting possible proceeds from “bone and ash recycling,” the projected net profit per slave laborer comes to RM 1,631, about $652, or, adjusted for inflation, $10,568 in 2019 dollars. (The exhibition curators used a different rate of exchange than I had.)

Here, on this single piece of paper, was a revelation seemingly worthy of the Nazis: the value of human life reduced to a cold calculation of profit and cost. My father was an alumnus of the labor camps and I desperately wanted to use this elegantly awful document in the book I am working on about Nazi documents.

But there were problems: no letterhead, no date, and no signature, not even a rubber-stamped one. This absence of sourcing made me wary. The last thing I wanted was to inadvertently undermine this horrible history because of a suspect document.

Natalia Aleksiun, professor of modern Jewish history at the graduate school of Touro College, said Holocaust deniers have tried to leverage even minor historical inaccuracies to discredit the entire history of the genocide.

While conducting her own research, she had found herself on websites that were “not only spewing hatred but engaged in discovery and discussions of how words and terms were translated, serious discussions.”

Years earlier I had interviewed Franciszek Piper, the Auschwitz historian largely responsible for the downward revision of the number of victims at Auschwitz from 4 million to between 900,000 and 1.1 million. After the camp was liberated, Red Army investigators had simply multiplied the theoretical capacity of the gas chambers by the theoretical maximum number of days of their operation. Piper instead analyzed transport logs and other factors in deriving his lower figure, which has largely been accepted by historians. Piper ruefully recalled how Holocaust deniers gleefully pointed to his findings to discredit the genocide entirely, despite his strenuous protests noting that most of Poland’s Jewry was already dead by the time the industrial-size gas chambers became operational.

Searching variations of “SS Rentabilitatsberechnung,” “SS Profitability Calculation,” or “SS prisoners 270 days,” I was surprised to see it come up many times in many languages. Interestingly, no matter the language—English, German, Russian, Hebrew, or Polish—every reference faithfully reproduced the same numbers and math.

Yet every citation, and everyone I contacted, had quoted what turned out to be a secondary source. Searching for the original often led to a trail of footnotes citing other books but never the document itself. The brave new world of internet copy-and-paste had spread it around even more.

The earliest reference—and the one cited by a curator of the Auschwitz exhibition—was from Eugon Kogon, a respected Catholic journalist and an outspoken anti-Nazi who was imprisoned at the Buchenwald concentration camp for six years. Kogon is often credited as the first historian to write of the concentration camps in detail.

The Rentabilitatsberechnung appears in his 1946 book, The SS State. Today, an English translation of the more popular 1950 rewrite, The Theory and Practice of Hell, can be downloaded for free.

“Let it not be thought that this calculation is my own handiwork,” Kogon wrote. “It comes from SS sources, and [concentration camp head Oswald] Pohl jealously guarded against ‘outside interference.’”

Kogon provides no further details or context about the document—who wrote it or when, where it came from, or how it had come into his possession—nothing. The curator of the Buchenwald Memorial museum, Dr. Harry Stein, had previously reviewed Kogon’s archive and confirmed to me that he has never been able to find the original source.

Yet, none of this surprised Robert Jan van Pelt, the preeminent Auschwitz expert and lead curator of the Auschwitz exhibition, which was produced by Musealia, a Spanish exhibition company, in cooperation with the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum in Poland. The Museum of Jewish Heritage has extended the exhibit’s run to next August.

“I’ve never seen anything but a transcript [of the profitability calculation],” van Pelt told me. “Never seen it anywhere, in any archive, or original, or carbon copy, or photocopy of a carbon copy.”

How, then, did it get to be so widely disseminated and find its way into the audio guide of a prominent New York museum exhibit in 2019?

“It fell through the cracks,” van Pelt said. Production of a new audio guide for the New York exhibit was running late. In the last-minute, hurly-burly deadline of getting the exhibit opened on time, van Pelt said the reference to the dramatic SS profitability calculation was left in. It appeared at the end of Stop 54, under the “Life in the Camps” section.

“The buck stops with me,” van Pelt said. “In some way, it’s my mistake that it stayed in.”

The calculation table is not on display in the museum nor is it in the exhibition’s catalog. Nor, van Pelt said, was it in the catalog or multilingual audio guide at the exhibit’s prior venue in Madrid.

Still, van Pelt cautioned against dismissing Kogon entirely based on the sketchy background of the profitability document.

Within days of Kogon’s liberation in 1945, the U.S. military’s Psychological Warfare Division asked him to assemble an in-depth report on conditions in Buchenwald, which became the basis of his later books. Kogon went on to become a prominent figure in West Germany’s cultural and political life and received many honors and awards. He died in 1987.

“I can’t believe he really made it up,” van Pelt said of Kogon and the calculation, “because he just doesn’t seem to be the man [to do so].”

Nevertheless, the Rentabilitatsberechnung doesn’t pass van Pelt’s sniff test for legitimacy. His own standards were molded 20 years ago, when British historian David Irving sued American scholar Deborah Lipstadt and her publisher for libel after she accused Irving of systematic Holocaust denial.

Van Pelt was the defense expert witness on the Auschwitz gas chambers. “I needed to show [the court] due diligence in everything I quoted,” van Pelt said. “Especially where it relates to the Holocaust, you feel the problem of denial is sitting there. I am more cautious than I would have been 20 years ago, before I had experience with Holocaust denials.” (Irving lost the case.)

Van Pelt admitted there was a strong temptation to use the document.

“The reason people are attracted to it is because it suggests, in a way that no other document does, that the Germans put a value on a life worth nine months or so many days of pure profit.”

The Germans did have a conscious policy of working labor camp prisoners until they dropped dead. The Nazi justice minister infamously called it “extermination through work.”

The SS did rent out workers to German industry for between RM 4 and 6 a day. Multiple Nazi documents attest to this.

Another Nazi document shows they did spend mere pennies—“pfennigs”—on food and shelter. Rations in labor camps were set at 1,300 calories a day for the unskilled (teachers, lawyers, white collar workers) and 1,700 for those with “useful” skills (machinists, welders, electricians, shoemakers). A man doing physical work needs about 2,500 calories a day. The body makes up for a caloric deficit by eating itself to stay alive. This policy of starvation was carefully planned. When applied to Soviet prisoners of war, one German general referred to it as the “annihilation of superfluous eaters.”

Bodies were stripped of gold teeth and valuables before incineration, though van Pelt said he had found no evidence from any Nazi source that bones were used for fertilizer. Given the obsessive nature of the Nazis to record everything, this is no small hole.

Kogon’s calculation attained greater legitimacy, and became more widely quoted, after it was included in Power Without Morality, a 1957 volume largely consisting of SS documents, edited by Reimund Schnabel. The 582-page tome has become something of a go-to reference about the operations and structure of the SS.

Photocopies of actual Nazi documents make up most of the volume. The SS Rentabilitatsberechnung, however, is set in plain text type. Next to it is the notation, “Z 32.” In the book’s Key to Abbreviations, “Z = Zitat” or “Quotations,” while “D = Dokumente” or Documents.

This meant Schnabel was not reproducing a document but reprinting a quotation.

That hasn’t stopped websites, historians, and museums over the last 50 years from misrepresenting “Z 32” as a document number or using the calculation as historical fact.

On Aug. 5, 1960, the Detroit Jewish News reported that Catholic delegates to a Eucharistic congress in Munich had visited an exhibition at the nearby Dachau concentration camp and were handed brochures containing “SS Document Z-32,” the profitability calculation.

Alex Pearman, an archivist at the Dachau Memorial museum, emailed me that he was unable to locate the source of the document mentioned in the 1960 article. Pearman, however, attached another poster image of the calculation—in English—from a 1964 exhibit at Dachau. It, too, had “Z 32” printed at the bottom.

From the Yad Vashem archives, I found a photo of a similar poster, in German, displaying the calculation at an unidentified exhibit. “Z 32” appeared at the bottom. Surprisingly, no one at Yad Vashem could tell me the source of the photo, much less the location of the exhibit. You can download a translation of the calculation in a Slavic language from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s website. Its source? The Museum of Yugoslavia.

Often a historian’s use of the SS profitability calculation is obscured by a cookie crumb trail of footnotes.

In 2004, Stuart Eizenstat described the SS calculation as, “one of the most chilling documents I have ever seen,” in his book, Imperfect Justice. He quotes the document and its arithmetic in detail.

Eizenstat is no intellectual lightweight or dilettante. He’s a former ambassador to the European Union, served as a deputy treasury secretary, and was a senior adviser to President Jimmy Carter.

His source for the SS document? A footnote cited in a German book about Nazi slave labor. That book, in turn, footnoted yet another German book about Nazi treatment of its enemies. This book’s source? Schnabel’s Power Without Morality.

In explaining the “Zitat” entries, Schnabel wrote, “In each case, the quotations indicate their accurate source.” Except there is no “source,” only a description: “Profitability calculation of the SS Exploitation of the prisoners in the concentration camps.”

“We need to be extra, extra, extra cautious precisely because we live in a time when every little detail that might be a misquotation, a historian missing a comma somewhere, becomes a political paddle against the truth,” said Aleksiun of Touro College. “This is not some Holy Grail of Holocaust scholarship that if we lose the document we lose the truth.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Mel Laytner, a former foreign correspondent for NBC News and UPI, is the author of What They Didn’t Burn: How Hidden Nazi Documents Proved a Survivor’s Holocaust Stories.