My Hanukkah in Hell

Looking for latkes during the Romanian revolution

I couldn’t believe my eyes. It was Dec. 22, 1989, and I had just driven up to Castle Hill in Budapest for a quick visit to PressInform, the semistate agency that kept an eye on foreign journalists while providing us access to government officials. Everyone was gathered around the television when I walked in, glued to a live broadcast from Bucharest. Politicians in suits, Romanian army officers, and poets in knitted sweaters were filling the screen. PressInform’s telex machine in the back room was clacking away, its alarm bell going off every couple of minutes.

“Ceauşescu is on the run!” Someone said. “He just fled from Communist Party headquarters by helicopter, people have broken into the building and these guys have taken over national television.”

In a flash, an idea came to me: Tonight was the first night of Hanukkah and I was just finishing my book on Jews in Central and Eastern Europe, which I had begun, in Romania noch, during Hanukkah in 1985. What a perfect ending!

I could just drive down to the Romanian city of Timişoara and shoot the Hanukkah party in the kosher kitchen run by the aptly named Mr. Pickle. And since there would surely be celebrations on the streets, just as I had seen and shot in Warsaw, Berlin, Prague and Budapest, I could take some pictures, sell them to newspapers, and earn a little cash.

Reader: Please understand that I wasn’t a real news photographer. In fact, in 1985, I was still selling office supplies in Atlanta. But that was the year I decided to become a journalist, so I moved to Hungary and started taking pictures. When the revolutions—or let’s just call them “the changes”—of 1989 started happening, I managed to Zelig my way into just about every big event, got in some decent shots, and sold them to newspapers and the wire services

On that day, Dec. 22, I had no idea that the dreaded Romanian secret police, the Securitate, were locked and loaded and only minutes away from launching a massive counterattack across the country. They were out to find Ceauşescu and reinstate him. I was heading right into their gunsights, looking for latkes.

I was not completely clueless. I knew that the revolt against the hated dictator had started in Timişoara just a few days before, on Dec. 17. That is when the police and Securitate had arrested a dissident priest, Lazslo Tökes, and tens of thousands of citizens took to the streets of Timişoara and tried to stop it.

The police and Securitate opened fire. Scores were arrested and dozens shot.

Satisfied with a little bloodletting, the 71-year-old Ceauşescu, who had held absolute power for 24 years, flew down to Iran for a short visit on Dec. 19 and returned on Dec. 20. Figuring his Securitate had quashed the revolt, he decided to hold a massive rally in Bucharest on the 21st, so he could let everyone know he was still the boss.

Over 100,000 workers were bused in and given banners and flags to hold. They were all in the square when the dictator took the balcony and began speaking. But in this YouTube video, at 43 seconds, you can see his face when he realizes the crowd (except for the lickspittle sycophants in front) had turned on him. First, his face registers confusion, a moment later, fear, then a Joe Pesci look-alike security guard approaches with a, “We’re outta here, boss,” whisper in his ear. And it’s all on his face. If ever there was an “I’m dying up here” moment, this was it. Then the screen goes dark.

Although a series of tunnels below ground had been built for just such occasions, Ceauşescu and his equally hated wife, Elena, didn’t run that day, but stayed overnight in Communist Party headquarters. The following morning, on the 22nd, he figured he’d have another go at it on the balcony. Which lasted only minutes before the crowd lunged at the entrance doors of party headquarters and broke in. Nicolae and Elena Ceauşescu ran to the elevators, and instead of descending into their network of tunnels, they took the lift up to the roof, but it jammed near the top. Their guards pulled them out and they ran up the stairs, onto the roof and into a waiting helicopter just as the angry crowd burst onto the rooftop terrace, looking to tear them apart.

As I watched footage of their helicopter fly off, I thought of just how monstrous they were and what a mental institute they had turned Romania into.

Over the previous four years, I had spent a good two months in Romania (I would later be given my 297-page Securitate file, complete with 12 photos, as a souvenir) and I came to believe no country was this surreal. In the summer I would drive for hours through wheat fields outside of Iasi and arrive in a city and find no bread. I drove across massive hydroelectric dams in the Carpathians to find cities plunged in darkness. I drove past what seemed like endless oil wells near Ploesti only to pass gas stations with lines in front of them that stretched on for more than a hundred cars. And when, after a day or two of waiting for their turn at the pump, each Romanian was allowed to buy around five gallons of gas—per month.

It gets worse. Romanians were not allowed to have more than one 40-watt lightbulb per room and since heat was centrally controlled, winters were brutal and close to freezing—and that was inside. To cheer themselves up, Romanians could watch television: The first hour each evening was devoted to the deeds of the Ceauşescu family, followed by another hour of folk dancing and/or singing. Then TV went dark.

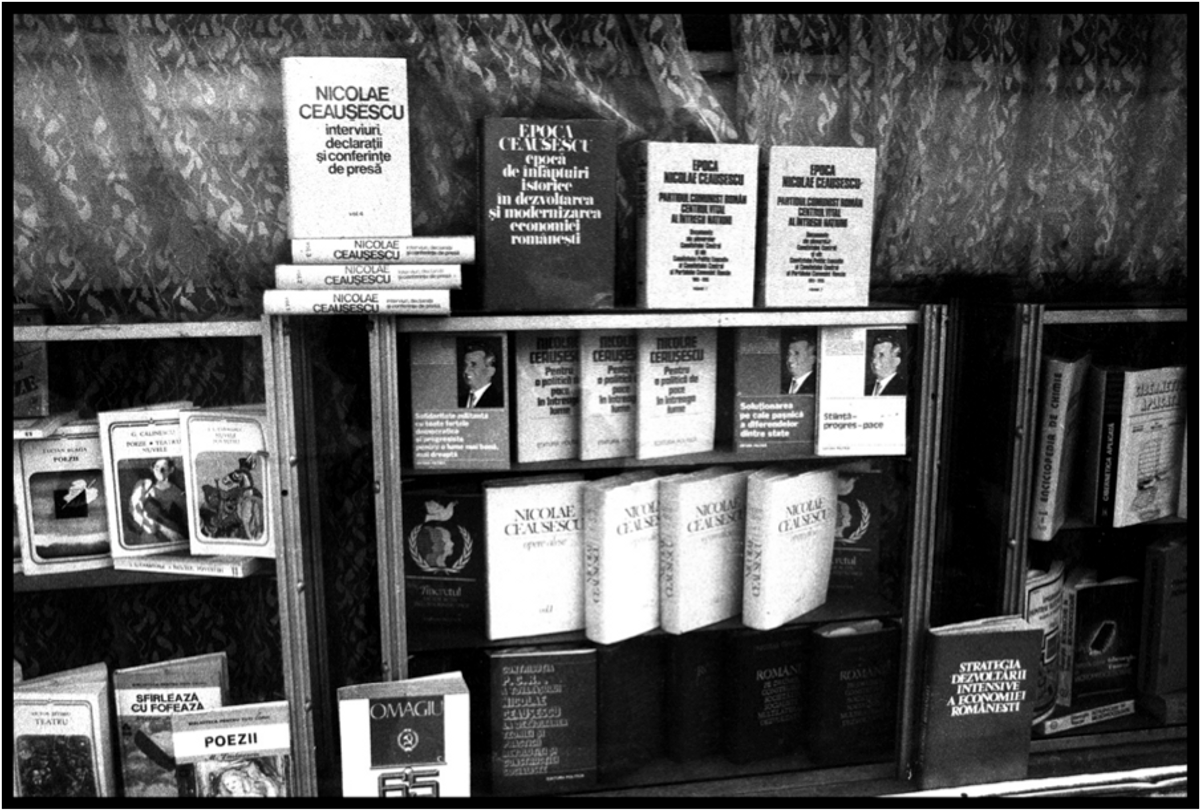

The photo here shows what Romanians could find in bookstores. Volume after volume supposedly penned by Nicolae Ceauşescu. And very little else.

Throughout Romania, ancient town centers were plowed under and in their place, with Ceauşescu’s “systematization” program, shoddy apartment blocks went up, often with communal kitchens. Just imagine: Hundreds of thousands of peasants who supplemented their crappy diets with their proud little garden plots were being forced into high rises.

Bucharest was the crowning achievement of the systematization program, where a fifth of the old town was razed, and the picture here gives you an idea of what a moonscape it looked like in 1985. Photographing wasn’t allowed and when I tried this earlier that morning, a Securitate official popped up like a jack-in-the-box, held out his hand for the film, and escorted me back to the Athenee Palace Hotel, where I reloaded the camera and slipped out the delivery entrance while he stood staring at the revolving door in front, like a goldfish waiting to be fed.

Abortions were severely criminalized, and starting in the late 1960s there was a spike in the birthrate. That meant Ceauşescu was growing an entire generation of brutalized, unhappy young people who, if given the chance, would rise up and kill him and his wife, which is what they did—after a kangaroo court—on Christmas Day, 1989.

But now we are back to 12:30, Dec. 22, with me in PressInform in Budapest and judging by what I was watching on television, I was sure it was curtains for this madman. I phoned a photographer I knew, Tamas Revesz, and told him, “Get your cameras, let’s go to Timişoara. I’m sure they’re dancing in the streets.”

I told Tamas it would be a cinch to earn some money selling pictures of celebrating Romanians, and we would have the added benefit of having potato latkes with Mr. Pickle. “Be out front in 30 minutes,” I said.

I then called a few numbers I saw on the bulletin board at PressInform. I knew the larger American papers would rely on the wire services for photos so I phoned Newsday, which had recently started a New York Newsday edition. Whoever was on the photo desk told me exactly what to do: Shoot the photos, go to an airport, yell out if anyone is flying to New York, give him or her the film and phone this number again with the name of the person bringing the film. Someone from Newsday would wait at the airport for them. I then phoned The Observer in London (The Guardian’s Sunday edition) and they told me the same thing.

And with that, we headed southeast. By the time we got to the border, there wasn’t a car in sight. No one was driving into Romania. And Romanians certainly couldn’t get out.

We crossed over at 6:00 p.m. and even in the winter darkness it was clear a half century of progress had vanished beneath the wheels. Hungarian roads might have been mostly two-lane blacktops, but the majority were smoothly paved and well marked. Almost all the towns in Hungary were brightly lit, with frumpy little town centers freshly painted and where restaurants served decent and occasionally excellent fare. Well-stocked gas stations stood at the entrance and exit of every town.

Then Romania, and presto: The roads were badly paved, potholed and undulating for no reason other than no one particularly had wanted to pave them. The villages could not have looked sadder and more neglected, and were so dark you could barely see them. The few gas stations we passed were, of course, closed.

A few minutes later we were driving through the city of Arad and, right in front of the city’s neo-Gothic city hall, hundreds upon hundreds of people had gathered and were cheering the fall of the dictator. A few people were clustered on the balcony yelling down at the crowd, who were responding as if at a rock concert. “Jos Ceauşescu!” (down with Ceauşescu) and even more important, “armata noastră este alături de noi!” (our army is with us).

“Stop here?” Tamas asked. I shook my head.

“Got to be a much bigger demo in Timişoara,” I said and we headed another 30 minutes south and drove into the city that spawned the overthrow of the dictator.

We passed the city limits and it all went as silent as a tomb. Not a soul around. Not a car on the streets. We drove on and on, kilometer after kilometer, and everything was shuttered tight, the traffic lights were all on blinking mode.

“Jesus,” I said to Tamas, “this is like one of those Western movies when someone rides into town and says, ‘It’s quiet here. Too quiet.’ Then the shooting starts.”

He looked at me. “Not funny, Ed.”

As we drove closer and closer to the center, we began to hear what sounded like thunder. But it wasn’t. It was gunfire. Lots of gunfire. And as if to postpone arriving at our destination, I kept driving slower and slower until an army road block stood before us, complete with tanks and armed soldiers running into the city center and out of it.

We got out of the car and approached the soldiers, all of whom looked like young conscripts. Since much of Timişoara spoke Hungarian (they called it Temeszvar) Tamas asked them if we could go through.

“Are you crazy!” they asked. “Why?” And the two of us pointed half-heartedly to our cameras, as if a game warden had caught us with ducks shot out of season.

One of the soldiers let fly with a string of Hungarian curses (and no language offers curses more colorful than Hungarian) as he jabbed his finger in the air and motioned for us to turn around and leave.

“What did he say?” I asked.

“That we should familiarize ourselves and our mothers with a certain part of the anatomy of a large horse,” Tamas said

While taking that in, a woman was being led away past the tanks, wailing and crying because her son, she’d been told, had been shot or wounded. We couldn’t tell.

Tamas and I swallowed hard. “So you think there’s a Hanukkah party tonight?” he asked. And since both of us now had feet so cold they could have frozen off, we decided to drive back to Arad and get some shots of that exquisitely peaceful rally in front of City Hall.

A few minutes later, the moment we drove into the square in Arad, the sound of machine-gun fire split the air. Suddenly, the entire crowd of several hundred, if not thousands of people (you could never tell because there was barely any street lighting) scattered in every direction.

Several thumped into my car, others scrambled across it as they ran from flying bullets. “Shit, what do we do?” we asked each other. It would be too hard to photograph people running in the dark and even I was smart enough to realize using a flash would only tag a “shoot this idiot” sign on my forehead. Then it came to us. “The hospital! That’s where they’ll bring the wounded! And they have light!”

Tamas asked a man running alongside the car where the hospital was. He jumped in the back seat and was glad to get away from the square. I followed his directions and five minutes later we were bringing our camera bags into what had to be the city’s main hospital.

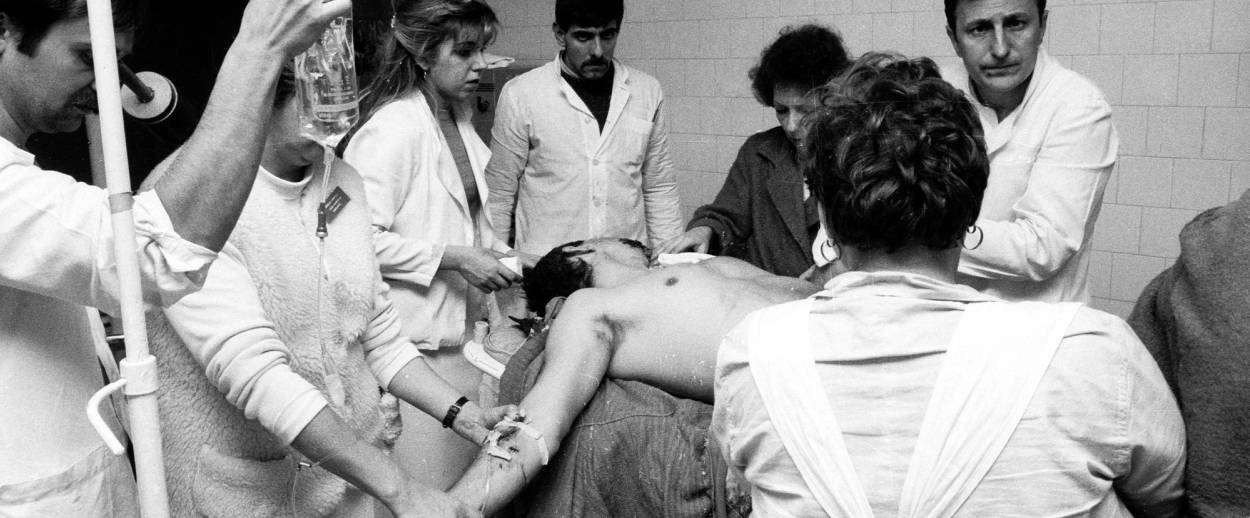

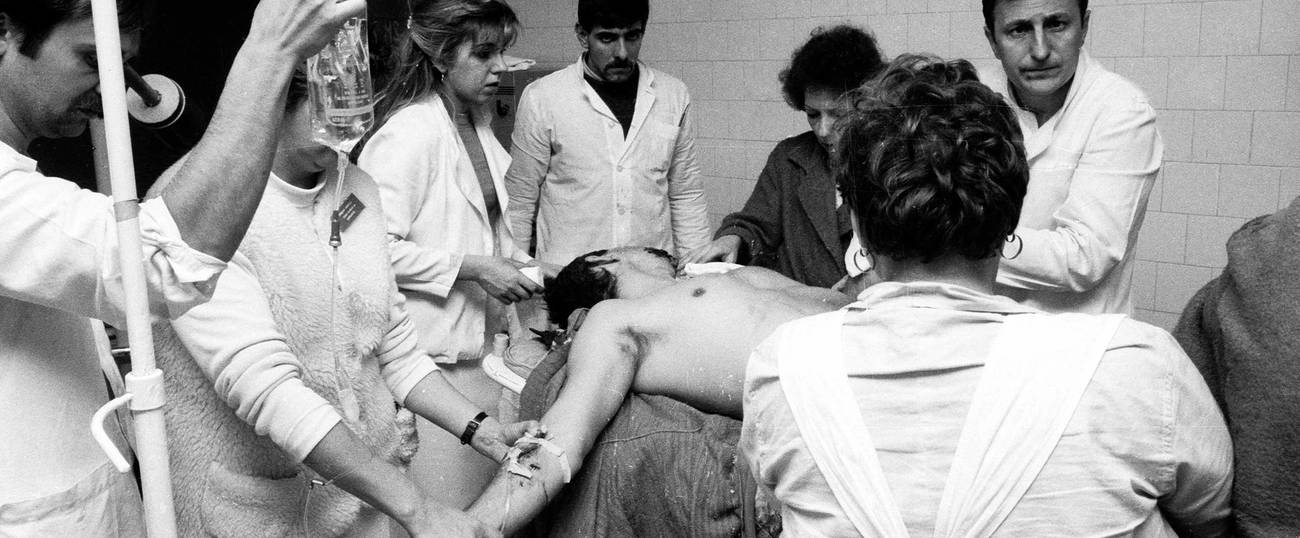

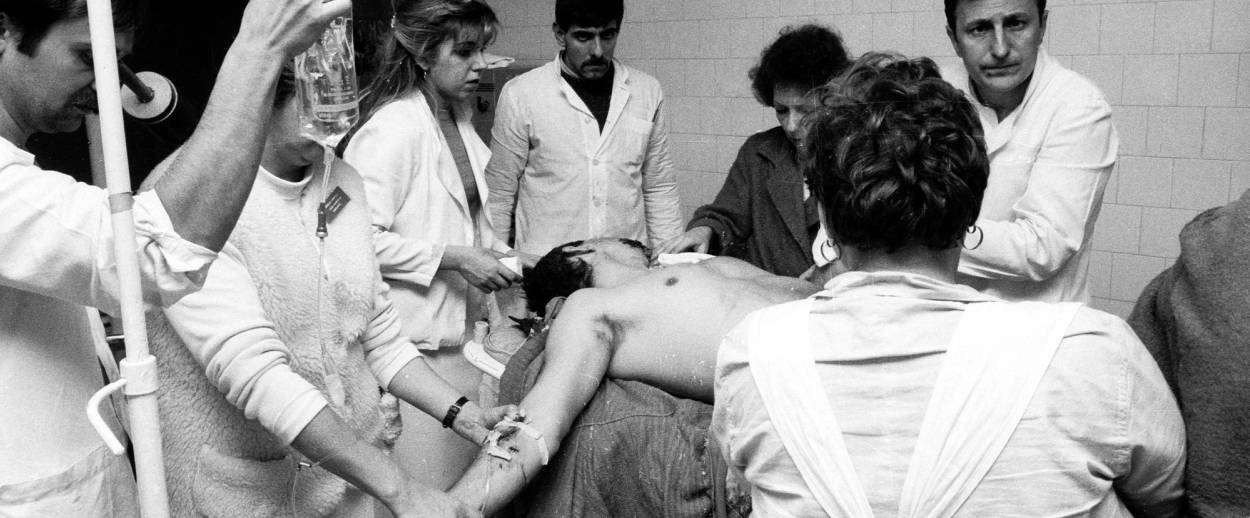

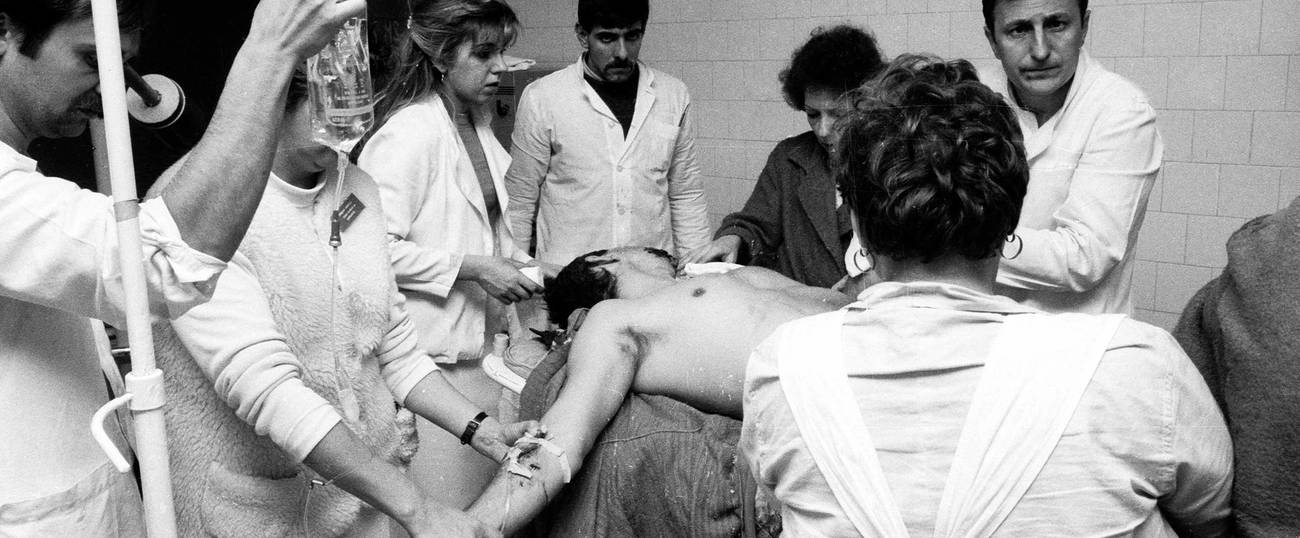

Doctors and nurses were running into the emergency room laying out bandages and blankets, dragging in oxygen tanks and piles of clean towels and sheets. It wasn’t long before they brought in the first soldier. He had been hit. Directly in the face. There wasn’t much life to save but the doctors and nurses did their best. It was now 10 p.m. and the sound of gunfire was growing louder and louder.

In countries where all news was fake news, the Romanian rumor and conspiracy mill ran rampant, and as we were waiting to see bodies and the wounded coming in, one man told us, “Did you hear! The Securitate hired a group of Palestinian terrorists, who went into a movie theater in Timişoara and machine gunned everyone in it!”

Our response: “Who goes to a movie during a revolution?”

A few minutes later we asked, “How come they are bringing in so few wounded?” The answer, ”The Securitate are such good shots they kill every time. There are no wounded.” I rolled my eyes at that one.

Then, “Securitate is sending helicopter gunships from Timişoara to shoot up this hospital!” That one scared me shitless until someone said, “How can they find us? There are practically no lights on!”

During the next few hours, bodies did come in, so did the wounded. Tamas took pictures and so did I, with me dropping cans of film into two plastic bags: one for Newsday, the other for The Observer. Then, a few minutes before dawn around 6 a.m., a convoy of trucks and cars that had delivered supplies to the hospital was getting ready to drive back to the border, while another convoy was crossing in from Hungary.

We didn’t know it then but later that day John Tagliabue of The New York Times and four other journalists were arriving in Timişoara, only to have their cars splattered with machine-gun fire, wounding John and three others. They were medevaced out to Yugoslavia two days later but in all four cases, it was a close-run thing.

Tamas and I sped out of Arad with the convoy. Twenty-something ambulances, private cars and trucks laden with goods were coming in, but that was not our story. More important, they were blocking the road, and I made my way past them on the soggy, grassy shoulder, caking my wheels with mud, regained the road and drove as fast as I could to the airport in Budapest, which I needed to reach before the 11 a.m. Pan Am flight to Kennedy. That’s where I did as I was told: I yelled out who was going to New York and who was going to London. In a moment I had my couriers and I ran to the pay phone nearby.

I never saw those pictures or negatives again, but in 2014 as Rabbi Michael Paley was introducing me to people working in the New York Jewish Federation, one of them was Noel Rubinton, who said to me, “Romania?”

My eyes bugged out.

“I was on the photo desk at Newsday 25 years ago. Loved the pictures.”

I returned to Timişoara on Jan. 2, 1990, with Imre Karacs of The Independent in London, where I shot more pictures. Soldiers were patrolling the streets, an armored personnel carrier stood in the town center, and locals were lighting candles on it and leaving flowers. It was, after all, the frightened, barely trained teenage conscripts who had defended the populace from the brutal, professionally trained Securitate.

Imre needed to interview an army colonel and his staff who had taken over the running of the city for the National Salvation Front, and as we left I asked Imre if we could make one more stop. “But I don’t need any more interviews,” he said. “Do you need any more pictures?”

“Just one,” I replied, and we drove over to Strada Gheorge Lazar, made our way into the Jewish community office next to the synagogue, and said hello to Mr. Pickle (OK, I confess: He spelled it Pichel).

“Where were you for Hanukkah, Serotta?” he asked as he and Elisabeta Sfetca were preparing lunch for the few elderly Jews still living there.

I told him I had actually tried to come.

“Meshugge,” he said. “Well, I certainly didn’t.” We didn’t lose any community members,” he said, “and there were a lot fewer people killed than we originally thought. Thank God.” Then he said, “Hanukkah’s over now so you won’t get any latkes, but can you boys stay for lunch?”

Since I had been eating in Romanian Jewish soup kitchens for years, and loved them so much that a decade later I convinced Ted Koppel of ABC News Nightline to let me devote an entire film to the one in Arad, of course I said yes. But Imre tapped his watch and shook his head. Something about a deadline. I sighed. And I knew my days as a news photographer had already ended.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Edward Serotta is a journalist, photographer and filmmaker specializing in Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe. He is the head of the Vienna-based institute Centropa.