What Was Brexit Like, Daddy?

London, on the night Britain left the European Union, during a brief lull in the culture wars to allow one side its victory dance

“C’est la vie to the European Union! I’ve been waiting 30 years for this!” The man on stage was buoyant. He punched the air. The crowd roared. A police horse shat on the ground. A singer swiftly took to the stage and started belting out a Tom Jones cover: “It’s not unusual to be loved by anyone!” he bellowed into the night sky. The crowd cheered, more half-heartedly this time. They waved British flags. People climbed onto the statue of Winston Churchill near the center of Parliament Square just outside the House of Commons where we all stood. They seemed excited. They shouted and cried and cheered some more. The thousands gathered there had waited years for this moment. And it was almost about to happen. Smoke filled the air. We were ready.

***

On Friday, Jan. 31 at 11 p.m., the United Kingdom left the European Union after 47 years as a member, in one form or another, of the great supranational European project of our age. It has been a fraught three and a half years since the June 23, 2016, referendum in which the British public voted, by 52% to 48%, to leave. The Brexit vote, as it became known, cleaved Britain in two. Two camps, leave and remain, fought over the result pretty much as soon as it was in. Leave urged us to—as Prime Minister Boris Johnson repeated throughout his December election campaign—Get Brexit Done. Remain wanted to either overturn the result or force another referendum.

Last Friday it all ended—at least for the moment. I was in central London, making an evening of it like so many others. I was there to hear what the people were saying, and to see what they were doing, on a night that was, whether you love or hate it, the most significant for my country since the end of World War II.

My first stop was a bong party, so named for the bongs of the clock Big Ben, which would have chimed to celebrate Brexit at 11 p.m. had the clock not been undergoing refurbishment. The party was in Cannon Street near London’s financial district. I arrived at the apartment along with a friend. A British flag had been propped underneath the door in order to keep it open. But it hadn’t worked and the flag lay crushed beneath. It might have been a metaphor except it would be wrong. That night no British flag was getting crushed. That night the flag fought back.

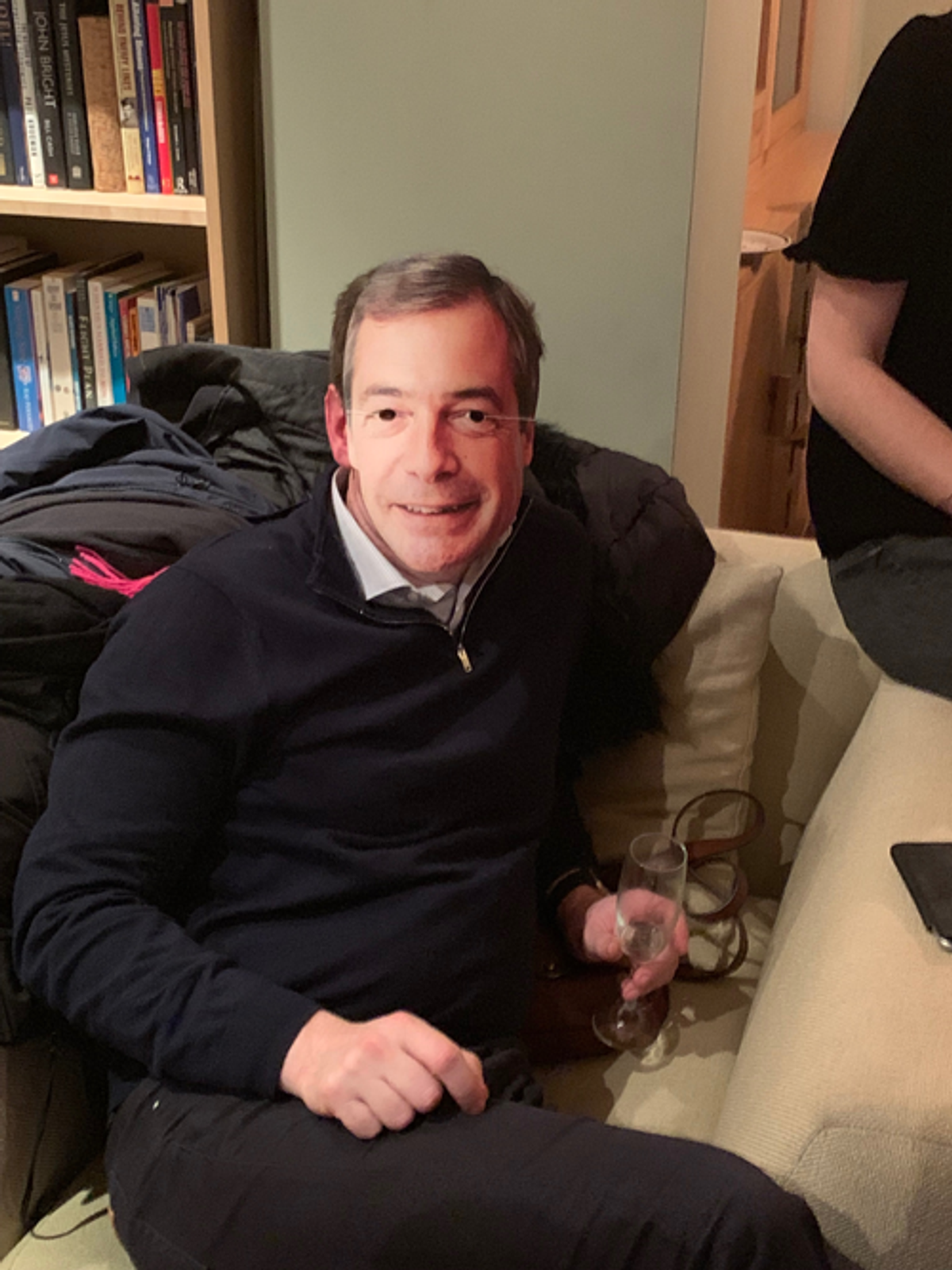

Inside, the apartment was small and thronged with people. Everyone was sober; the mood seemed calm and not especially celebratory. But the preparations had been attended to. Amid the wine and nibbles were British flags. And among the flags and wine were a few dozen masks of the face of Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage. I was assured that come 11 p.m. they would be donned by the revelers.

In the background, music from Queen Elizabeth’s 1953 coronation played.

The host was Dirk, a lawyer from London, who had been campaigning for Brexit since 2002. Long before it was fashionable, he told me. Dirk worked for the famously Euroskeptic MP Bill Cash almost 20 years ago, which, in Brexit terms, is like buying Apple stock in the 1990s.

Dirk was wearing a pinstriped, double-breasted suit with a polka-dot tie. His shirt was double cuff. He held his glass properly, that is to say, by the stem, his fingers careful not to warm the liquid.

I asked him why he had been such an ardent Brexiteer for so long. “I studied law,” he replied. “And it soon became clear to me what the cost and implications of EU membership were for the U.K. We were subject to an alien system of law the principles of which I did not agree with.”

“Simply put: [In joining the EU] we had adopted a political principle as the jurisprudential linchpin of the legal system—everything is geared toward ever greater union.”

On the sofa behind Dirk sat two women, one of whom, a gregarious blond lady, was holding forth vigorously. Her conversation was invading ours. “I don’t care if the world is going to shit as long as I’m getting laid,” she said.

Dirk continued: “I feel relieved today, combined with a mix of optimism and regret.”

“Do you know how much I’d cry at your funeral if I knew you hadn’t had enough sex?”

“The thing is, the British people never voted for a political union.”

“In the end, sex is what matters.”

I left Dirk and milled around for a bit. I spoke to another guest at the party, who told me that even though she voted for remain she was glad we were leaving. “For me, it was all about what happened after,” she said. “It was about how close it came to not happening, to the vote not being respected. In the end, it came down to a democratic principle.” A friend of hers came up and interrupted us briefly:

“Sorry, I have to leave, Bertie’s puking again.”

I asked her where she thought things would go from here. “Now, I hope we can all get on and make the best of it,” she replied. “It’s about the five stages of grief. Up until now we’ve been stuck on denial and anger. Now hopefully we can move on to acceptance.”

She made me think. On my travels, especially in the United States, these past three and a half years, I had been asked the same question over and over: Why, after the vote, could you not just move forward and get it over and done with?

The answer is that Brexit was never solely about politics. It was in fact a culture war. And in an era where the divides of left and right have drifted from their traditional moorings, the 2016 referendum gave the British a whole new way to identify politically, linked, moreover, to the essence of who they were as people. It was intoxicating.

Sophisticated with an international outlook? A globalist with contempt for national pride? Then naturally you voted to remain in the European Union. Concerned about British sovereignty and a democratic deficit? A tiny bit of a Little Englander? Then it was leave for you.

And being a leaver or a remainer was never just a political position; it was a tribal marker, and people can waver in their tribal allegiances, they can even, at a push, switch them. But they will never, ever abandon them. This was a conflict that could not be solved through compromise, and certainly not by anything as dull as policy. One side needed total victory. Leavers and remainers could only come together when one side had no purpose anymore, that is to say, had ceased to exist. Truly, it was zero sum.

It is obviously no longer possible to be a remainer. Most of the defeated have now accepted the reality of Brexit and hope things won’t be too bad. Some hope that things will be terrible so they are proved right. For a further, and smaller, grouping Brexit means only that their tribe has morphed from remainer into rejoiner. But then some people just love the drama.

I voted remain, which was no surprise. As far as tribes go, mine was set from birth. I am from Hampstead in North West London, the fundament of British Champagne socialism. I attended the type of private schools revered by my class (comfortingly expensive, remorselessly liberal; ZIP code attuned). I have a degree from Oxford. I am Jewish and, perhaps inevitably, work in the media. I am a child of (affluent) immigrant parents and grew up in multicultural ease around the importance of food, émigré intellectuals, and the imperturbable cordiality of the British professional classes. I have lived abroad. As a privileged child and, later, for almost a decade as a foreign correspondent, I have traveled to more countries than almost anyone I know (no mean feat). I count among my friends and acquaintances: politicians, diplomats, writers, artists, policymakers, generals and the odd head of state. I’ve given a TED talk. I’ve been to Davos.

I am not merely the definition of everything a remainer should be: I am a parody of it. I am what the journalist David Goodhart would call an “anywhere” (from the liberal establishment, defined by educational/professional achievement over geography, globalization over localism). I am a representative of what the right-wing press calls the liberal metropolitan elite; and I am what Stalin would have once called (for a variety of reasons) a “rootless cosmopolitan.”

And yet, at this deliberately absurd party on the eve of our departure from the EU, talking to these people, all of whom were entirely reasonable, I found that there was a convergence. I too agreed on the need to get Brexit done; I too now want it to be a success. But it’s more than this. Dirk is a leaver. It is his tribe. He wears it, almost literally, on the pinstripes of his suit, which is why he was so happy to let me photograph him in it, even though he knew exactly why I wanted to photograph him in it. He is self-consciously charming like the Conservative MP Jacob Rees-Mogg. He is expected to be the parody of an English gentleman (for tonight at least) and so he is—understatedly, though, of course. He wouldn’t do it any other way.

So there we were, all representatives of our tribe. And I looked around, and there were the music, the masks, the suit, the bongs, the party: Despite the kitsch it was sincere. But it was also ironic, and what is irony, I thought, if it is not cosmopolitan?

I circled back to Dirk as I prepared to leave. “Britain joined the European Economic Community [as it was then] because it was the sick man of Europe, if we weren’t we never would have joined,” he told me in conclusion. “Brexit is a sign of a renewed national self-confidence.”

I made my way toward the exit just as a man on a sofa tied a Nigel Farage mask to his face. “Beneath this I’m smiling,” he said.

***

Walking toward Parliament Square, I was surrounded by people festooned in the Union Jack and the journalists and photographers chasing after them to record it all. It was nearing 10 p.m., roughly an hour before we, finally, would Brexit. I arrived in the square and watched the people on the stage. The crowd was antsy; it felt like people should have been happier than they were. A sense of pervasive anticlimax hung in the air. People were looking for things to do. “Let’s start a stampede,” said a youth in a baseball cap in front of me. The smell of cannabis lingered.

A chant went up: “We voted to leave, we voted to leaveeee, fuck off Labour, we voted to leave.”

The crowd tensed. A man had come on stage. “Do you want Nigel?!” he screamed. The crowd cheered. “I can’t hear you! Do you want Nigel?” The crowd screamed, a bit impatiently this time. “Here he is, the one and only Nigel Farage!”

Farage came on. He grinned like he always does. He bellowed that in 14 minutes we would leave the EU. “This is the single most important moment in the modern history of our great nation!” he shouted into the mic. “We did it, We DID IT!” He started to speak about freedom and democracy but the sound was bad and it was hard to hear him.

But he didn’t care. This was his Churchill moment; he was going to milk it. “The war is over,” he bellowed. “We have won!”

A group of police carrying an unconscious woman charged through the crowd: “Get out of the way!” “Move!” they scream. A teenager in front of me swigging from a can of beer mumbled about the “fucking old bill.”

A man standing next to me chuckled and showed me his phone. It was Twitter. “Look, the fucking remainers are going bat-shit over us all here.” I checked my phone. He was right. Twitter was filled with users mocking the congregation of British flags and the people wielding them in the square, and once more I thought of the great culture war I’d lived through these past few years. People online were angry.

An abiding characteristic of social media, and one I now realize is not a bug but a feature, is that it allows you to see people slowly lose their minds in real time. In the United States the biggest cause of this phenomenon has been Donald Trump; in Britain it was Brexit. Lord Andrew Adonis was once a serious man. He is a former secretary of state for transport and chairman of the National Infrastructure Commission as well as being a former adviser to the Number 10 Policy Unit. Once he briefed Tony Blair. Now he tweets about plots involving the BBC “radicalizing” the public to vote for Brexit.

What is it about Brexit—and indeed Donald Trump—that transforms once-sane (and clearly intelligent) people into hawkers of absurd conspiracy theory? The answer, I decided, in both cases, comes down to the manner of their ascension: the unexpected loss of a vote by the favorite and establishment choice. Seen as this, the impulse is the same tawdry one that guides all conspiracy theorists, from mutterers about the Rothschilds to chemtrails bores. The world is not as it should be: Who is to blame? And, more piquantly: Who duped the sheeple? The questions are always the same. But from the BBC to Russia to journalists to corrupt financiers the answers are always different.

Finally, 11 p.m. struck; everyone cheered. Fireworks went off and more smoke filled the square. I talked to people who were desperate to talk to me. This is not always the case. Whatever else this evening was, it was an orgy of the marginalized given voice. These were, you felt, people not used to being listened to.

The crowds began to drift out of the square, heading toward various tube stations. I pictured Dirk back at the apartment drinking Prosecco in a Nigel Farage mask while listening to unionist songs. I thought of Britain’s tribes, and I hoped that we might find common cause in the struggles to come.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

David Patrikarakos is the author ofWar in 140 Characters: How Social Media is Reshaping Conflict in the Twenty-First Century. His Twitter feed is @dpatrikarakos.