Israel’s Nastiest Political Rivalries

You think American politics is cutthroat?

As Israel faces the prospect of its third election in less than a year, the one factor dominating Israeli politics is Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s continuing hold on the leadership of his Likud party. As Gideon Sa’ar’s recent failed challenge to Netanyahu for the party leadership demonstrated—he only got 27.5% of the vote—Netanyahu continues to be effective at rebuffing internal challenges to his leadership. This ability to manage intraparty squabbles is a key element to Netanyahu’s longevity, and stands in stark contrast to the typically roiling nature of Israeli politics throughout Israel’s short history.

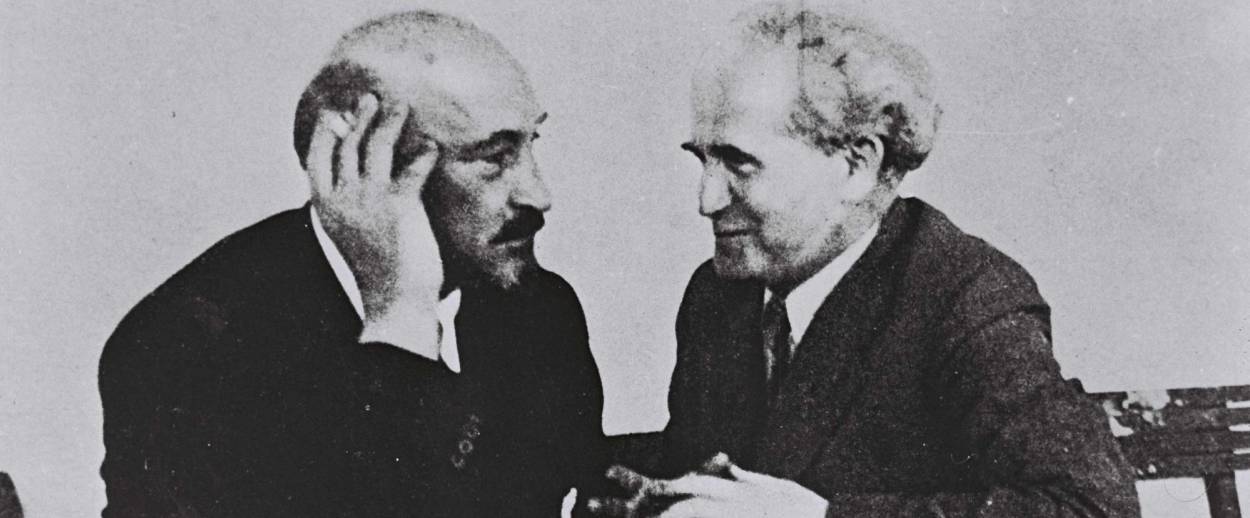

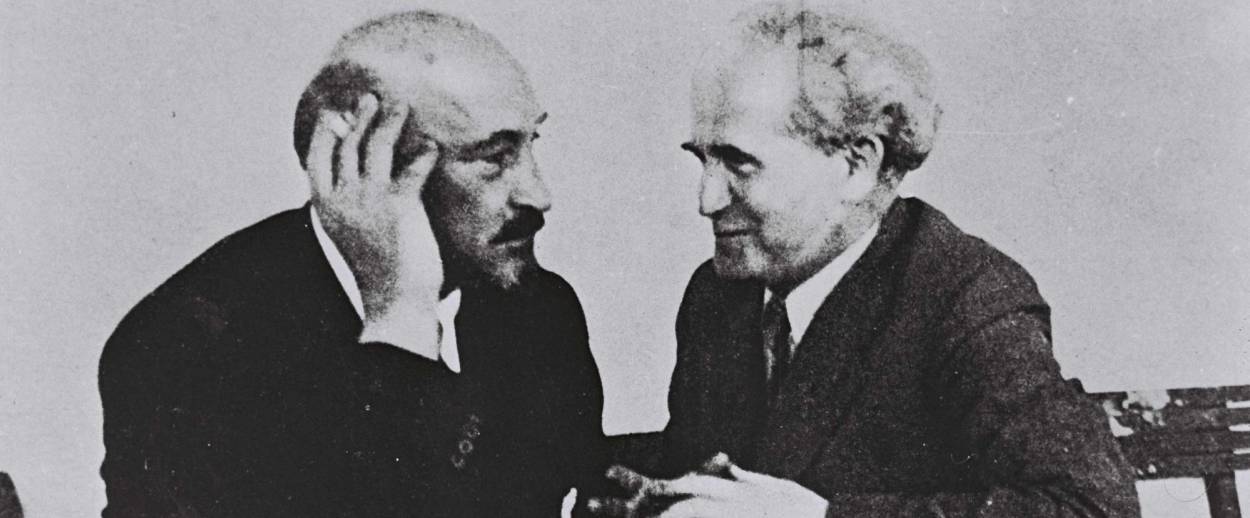

Rivalries defined Zionist politics even before the state came into existence. David Ben-Gurion, who would become Israel’s first prime minister, was a sharp-elbowed and particularly effective infighter. As Amos Oz, Israel’s best-known novelist, quipped about Ben-Gurion: “Verbal battle, not dialogue, was his habitual mode of communication.” Ben-Gurion emerged as the leader of the Zionist labor coalition because of his successful efforts against Zionism’s previous dominant force, Chaim Weizmann. Weizmann and Ben-Gurion had been rivals since the 1920s, and Ben-Gurion recognized that his path to the top necessitated the defeat of Weizmann. Ben-Gurion was not shy about his feelings toward the older man, referring to him at times as “loathsome carrion” and “a trampled corpse.” In 1936, Ben-Gurion told Moshe Sharett that “Chaim has already failed us here; he is certainly not capable of future leadership. I see not only the disaster that awaits us now because of this man—the cause of all our political failure in previous years has become clear as well.”

Unsurprisingly, Weizmann did not think much of Ben-Gurion, either. In 1940, when the two men were on a visit to the United States, Weizmann went to a White House meeting without inviting Ben-Gurion, or even letting him know about the meeting. Ben-Gurion found out about it afterwards, leaving him none too pleased. In 1942, in a direct exchange between the two men, Ben-Gurion told Weizmann, “If we had a state, we would have to shoot you. You’re a traitor.” Weizmann’s response: “And if we had a police force in the state, we would have to send you to a madhouse.” Weizmann also nicknamed Ben-Gurion “Brutus,” after Caesar’s assassin.

At the 1946 Zionist Congress, Ben-Gurion finally got his way, after insisting that “I will not serve on the Executive so long as Weizmann serves as or will serve as president.” This declaration led to Weizmann being deposed from his leadership post. While Weizmann would serve as Israel’s first president, it was a symbolic post, and Prime Minister Ben-Gurion made sure that the position had no actual power. The long and ugly fight between the two men only underscored the way in which Israeli politics were steeped in internecine warfare. As the historian and Ben-Gurion biographer Tom Segev observed, Ben-Gurion only did to Weizmann what Weizmann had done to his older rival, Zionism’s forefather Theodor Herzl. It should be noted that Ben-Gurion was also quite harsh on his rivals in opposing movements as well: He hated Betar founder Ze’ev Jabotinsky so much that he would not even let Jabotinsky’s corpse enter Israel. Jabotinsky was only buried in Israel in 1964, after Ben-Gurion was no longer prime minister. And he may have hated conservative opposition leader Menachem Begin even more. For years, he would not even mention Begin’s name, famously referring to him in Knesset debates as “the gentleman sitting to the right of Mr. [Yohanan] Bader.”

For the state’s first 29 years, Israeli politics were dominated by Mapai (later the Labor Party), which endured as a hotbed of internal rivalries. At the heart of many of these rivalries, with enormous implications for Israeli politics, was Golda Meir. American Jews tend to see Meir as a Jewish grandmother type, notable as one of the first female heads of a Western democracy. But the only way that Meir attained her groundbreaking position as prime minister was by being a very savvy and occasionally ruthless infighter.

Golda learned her craft by attending countless hours of meetings of pre-state labor and Zionist organizations. At these meetings, she watched Ben-Gurion—a master infighter—in action. At the 1946 Zionist Congress, Golda had to intervene to prevent a fistfight between Ben-Gurion and Weizmann ally Eliezer Kaplan. Ben-Gurion admired her toughness, and later called her “the only man in my cabinet.” Meir first became foreign minister in 1956, after Ben-Gurion maneuvered incumbent Moshe Sharett out of office. (He had also replaced Sharett as prime minister, so this was the second time he was displaced by Ben-Gurion.) Sharett was not only angry at Ben-Gurion for pushing him out, but also resented Golda, with whom he had been close, for taking his job. Sharett took his removal hard, writing in his diary after his ouster, “I am sad, sad, sad.”

As foreign minister, Golda had a running rivalry with her colleague Abba Eban. South African-born and Cambridge-educated, Eban was seen—and certainly saw himself—as more cultivated and refined than the Ukrainian-born Meir, who attended the Milwaukee State Normal School teacher’s college. Eban thought that he should be the face Israel presented to the world, and he let people know it. Meir, in contrast, had more of a “common man” approach, and poked holes at Eban’s pretensions. When told that Eban speaks five languages, she retorted, “so does the waiter at the King David Hotel.” When told that Eban wanted to be prime minister, she asked acidly, “of which country?” Eban got in his shots as well, mocking Golda’s mediocre Hebrew by asking, “She has a vocabulary of 500 words, why doesn’t she use them?” Meir gave as good as she got in response, though: “With such a limited vocabulary, why would I waste precious words on you?” Unlike Eban, she did eventually become prime minister, but even here, rivalries would play a role. She got the top job in large part because two other contenders, Yigal Allon and Moshe Dayan, were always fighting with one another, making Meir more of a consensus choice.

***

Meir’s replacement as prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, was involved in an even more legendary rivalry than the Meir-Eban one. Rabin and his nemesis Shimon Peres feuded for decades before Rabin’s tragic assassination in 1995. The two men had known each other since the 1940s, but their enmity reached a boiling point in 1974, when they both vied to replace Meir as Labor leader and prime minister. Rabin won—with Meir’s behind-the-scenes help—but it was close, and their contest would have consequences. Peres demonstrated enough support to compel Rabin to appoint him defense minister, and the hardball tactics employed in the race deepened their mutual hatred. Rabin, in particular, was angry and blamed Peres for the (not inaccurate) report that Rabin had suffered a breakdown while serving as IDF chief of staff in the run-up to the Six-Day War in 1967.

While serving in government together, the two men had some significant disagreements. One was over the development of the first settlements on land Israel had won during the 1967 war. Another was over the risky but ultimately successful hostage rescue operation of a hijacked Air France plane in Entebbe, Uganda, in 1976. In both cases, Peres was for, and Rabin against, and they fought it out via their allies in the press. The Entebbe struggle was particularly bitter, as both tried to take credit—and deny glory to the other—after the raid succeeded. Peres befriended the family of Yoni Netanyahu, the leader and martyr of the raid, and used his closeness to the family to signal that he had championed the operation. Rabin, for his part, used his position to try and keep Peres’ name out of official accounts of the raid. When Israeli movie producer Menahem Golan began work on a film about the raid, each of them petitioned him for more screen time for their character than for the other’s.

Rabin maintained his feud with Peres after losing the premiership in 1977. He wrote a 1979 memoir, Service Notebook, which was highly critical of Peres as a disloyal leaker, and he continued to criticize his actions as Labor Party leader. In 1990, Rabin dismissed Peres’ failed maneuver to oust Likud Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir as “HaTargil HaMasriaḥ”—the Dirty Trick or the Stinking Maneuver (translations differ)—and the name stuck.

Two years later, Rabin challenged Peres in an open primary for the Labor Party leadership, and won. Once again, Peres joined the cabinet under his rival, as foreign minister. This time, it was Peres who was the more dovish one, pushing surreptitious peace talks with the Palestinians that ultimately became the 1993 Oslo Accords. Three days before the signing of the accords, Peres could not stand the notion that Rabin was getting the credit, griping, “That man ruined my life. I’ve been working for him for over 16 years, and he doesn’t say ‘thank you’ to me. He’s crazy, and now he wants to hijack my ceremony. What has he done on this matter? Nothing. In that case, I’m not going to Washington. I prefer to resign my position as foreign minister. I’ll leave him the stage, that’ll please him.” Peres did not resign, but he did think about challenging Rabin, prompting Rabin to grumble, “Shimon will haunt me to the last day!” a few days before his assassination.

The bitter Rabin-Peres rivalry fascinated Israelis, and led to all kinds of armchair psychologizing. Israeli journalist Matti Golan described it as “much more than a political issue—it’s psychological and very complicated.” Columnist Yoel Marcus observed that “it is not an ideological dispute that separates the two men, but a deep personal grudge.” Amos Oz compared the old sparring partners to two bickering old women who needed to hold hands to cross a busy street.

The rivalry would have political repercussions beyond Rabin’s death. Benjamin Netanyahu, the brother of Yoni, whose family Peres befriended in order to tweak Rabin over his Entebbe hesitation in 1976, was elevated by Peres’ friendship and would later defeat Peres, who stepped in following Rabin’s death, in the 1996 election. This dueling spirit appears to have influenced Netanyahu as well, as we see from the way he has acted to squelch potential internal rivals from emerging inside Likud.

Even so, Netanyahu certainly encountered some bitter internal enemies on his rise, including fellow Likudnik Ariel Sharon. In 1996, Netanyahu unsuccessfully tried to keep Sharon out of his cabinet. Sharon did not forget. As prime minister, Sharon mocked Netanyahu mercilessly for his flip-flopping over the Israeli withdrawal from Gaza, saying in 2004: “After supporting disengagement four times, Bibi ran away.” Ehud Olmert, another Likudnik who would serve as prime minister, also hated Bibi and undercut him in his 1999 race for reelection.

As prime minister over much of the last decade, Netanyahu has been careful to prevent any Likud ministers from becoming too powerful. This effort to hold back budding talents has had political repercussions, with ambitious ex-Likudniks Avigdor Lieberman and Naftali Bennett deducing that Bibi was unlikely to cultivate potential replacements and thus going their separate ways.

Keeping Likud members from getting too powerful has certain advantages. It protects Netanyahu from backbiting within the party and also lets his supporters make the case that there are no realistic alternatives to his leadership. On the other hand, Lieberman’s refusal to bring his Yisrael Beiteinu party into a coalition with Likud, which appears to stem from the personal animus between the two men, is a crucial factor that may help determine the outcome of this next election. If this upcoming third election ends with someone other than Netanyahu as prime minister, historians may label the dénouement of this period of upheaval as “Lieberman’s revenge.” But if Netanyahu stays on top, his ability to manage internal rivalries that have upended predecessors will be a key element of his continuing success.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Tevi Troy is a Senior Fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Institute. He is a former White House aide and the author of four books on the presidency, including, most recently, Fight House: Rivalries in the White House from Truman to Trump.