Why Bernie Sanders Will Win Texas

A dispatch from Austin, Texas, ahead of the Super Tuesday presidential primary

Bernie Sanders, a Jewish socialist, stands a very good chance of winning Texas on Super Tuesday. As in the rest of the country, the Vermont senator’s success is proof that the center no longer holds, not in politics nor in life more generally. Theres no better place to sample the incoherence of the present social mix than in Austin, the state capital, a wealthy creative center built on liberal exploitation of Texas’ lack of an income tax and allergy to government involvement in much of anything.

On a Tuesday morning, out of the window of a Japanese coffee shop in an office complex in an old warehouse in east Austin, you can see a weedy meadow, rusty fences, and then a peloton of a dozen lycra’d-out cyclists speeding by low-slung houses built of time-beaten clapboard. This area east of I-35 was where redlining and a century of racist urban policy had shunted the city’s African Americans and Latinos, a policy that depressed real estate values and created the conditions for hipsters and yuppies and techies to swoop in decades later—many of them coming from high-tax, bureaucratized coastal hellscapes like San Francisco, bringing their decidedly un-Texan politics along with them. Some 1,000 newcomers are said to arrive in the state every day.

Austin’s built environment exhibits an underlying schizophrenia. Condos face scrapyards across a new light-rail line that almost no one rides; massive slope-roofed houses try to mimic—although it’s more accurate to say they mock—the architecture of the modest older houses around them. The interior of the Broken Spoke, the famous south Austin honkytonk, has barely changed since Tex Ritter played there in the 1960s; walk into the parking lot and you are suddenly in Bethesda or Metro Park.

At the Austin Democratic Socialists of America debate watch party on Tuesday night, held at a bar tucked at the end of a small bank of shops on the north end of town, I spoke to a Latino man in his mid-30s who wore a jacket from a municipal employees union and an Abolish ICE pin. Sanders holds wide support among young Latinos, the state’s rising political force. The man, who declined to give his name, lived in a historically black and Hispanic east Austin neighborhood; as an active union organizer he had been planning on voting for Sanders even if the Vermont senator hadn’t been the only candidate whose canvassers had bothered to visit his part of town.

“I get offers to buy my house every day,” the man noted. “Every day! Yesterday I got two postcards: Let me buy your house.” This was no promise of a coming windfall. For the assembled socialists, such hounding was an indecent assault on the social fabric, an illustration of the core problems that drove Austinians to Sanders or to the DSA. Everything is for sale; developers are alleged not to care about the consequences of their investments or about anything but themselves.

“The gentrification’s gross here,” agreed a nearby comrade, who looked like he was 25 at most.

***

Austin is a place with no real native industries—no oil or livestock or big railroad junctions, unlike other less hip and more expensive Texas metropols. It has become the 11th-most populous city in the entire country, largely on the strength of its coolness, its affordability, and its Texan freedom from government.

Sanders’ success in Texas comes from a disgust at the cascade of incentives and conditions that resulted in this success story. If Bernie wins Texas, or even comes close, it will help surface one of the major subtexts of American politics in recent years, which is the scorn that the makers of a given place’s prosperity now often harbor toward the very thing they’re helping to build. Austin has freshly opened Google, Apple, and Oracle campuses, along with a polarizing homelessness problem, rising costs of living, housing shortages, a frisson of social dislocation and creeping homogeneity—the same package of benefits and diseases that 21st-century urban prosperity visits upon Brooklyn and Portland and numerous points in between.

“The problems in Texas are largely driven by growth, the infusion of capital in ways that create concerns among people left behind,” said Daron Shaw, the Frank C. Erwin Jr. chair of state politics at the University of Texas. He is not convinced that Texan Sanders supporters are enthusiasts for socialism necessarily, or care how unworkable many of their candidate’s programs are in practice. Instead, they sense that something is wrong, something that only the Vermont senator seems to talk about or understand. ”He wants to turn this election into a referendum on the corruptibility of the system, and I wonder how much it matters that his solutions are radical and costly. I wonder if instead what matters is that he’s so committed to battling this problem.”

Like Donald Trump in 2016, Sanders appears to diagnose a crisis that his followers across the country sense at bone level but neither the popular culture nor mainstream politicians feel comfortable mirroring back. As Madeline Detelich, a graduate student at UT and a DSA activist put it: “It feels increasingly like we live in a city with a lot of rich people where everything is fine for them.” Ashkan Jahangiri, a 2017 UT graduate and public special educator who is a member of the Austin DSA’s leadership committee, summarized the core Sanders grievance with remarkable bluntness over the course of a short, exuberant speech during a commercial break at the debate watch party: “We don’t have the life our society’s abundance should be able to give us today.”

The debate watch drew about 40-odd people whose average age looked to be in the high 20s. The Knomad had a patio dotted with tasteful succulents; pizzas of high quality emerged from a discretely hidden kitchen. This was the kind of place where you didn’t have to put a coaster over your drink when you left for a cigarette—no staffer was going to clear it away; there’s no feeling of being hustled toward spending more money. The Knomad also has a cigarette machine selling $9 packs of both blue and yellow American Spirits, yet another sign of the place’s essential decency.

“Engage full rat mode!” one comrade bellowed when Pete Buttigieg, condemned to permanent rodent-dom by America’s internet socialists, asked the audience to imagine the horrors of a Trump versus Bernie race. Everyone chatted through a Warren-Bloomberg fistfight, then fell to a dead hush when the Vermont senator began talking about health-care costs. I am obligated to mention that the words “The Ruling Class Can Kiss My Ass” appeared next to a glowering Kinky Friedman on one attendee’s T-shirt.

Somewhere in the midst of all this, Amy Klobuchar talked about a Vanderbilt University study that had named her the most effective Democratic senator according to 15 different metrics, while Sanders and Warren had ranked in the bottom half. It struck me how irrelevant such a factoid was to everyone gathered at the Knomad. Klobuchar was talking rationalist politics against a force that was somehow supra-political—larger than a senator or even the Senate itself; certainly larger than the contrivance of a circuslike televised debate. “Bernie doesn’t talk about the left and the right as though one of them is totally other from us,” said debate watch attendee Heidi Sloane, founder of a farming program at a community for the chronically homeless and a DSA-endorsed Democratic congressional primary contender. “He talks about the top and the bottom, in a way where he thinks anybody should have a decent life. It doesn’t feel radical. It feels actually quite sensible. It shows how radical corporate greed and corporate power have set things up to be.”

***

The Texas primary is likely to see the same stark age divisions apparent in most other states. Like everywhere else, a 78-year-old is the candidate of the young. As Tara Pohlmeyer of Progress Texas explained, polling conducted by the organization showed that Sanders had plurality support among Texans under 45, leading Warren 40% to 20%. (Texans from 45 to 65 appear sharply divided, while those 65 and over tend to back Biden.) “Younger Texans are responding to his vision … the ways things are going don’t work for people who make under a certain amount of money, or who are under a certain age,” Pohlmeyer explained. At the same time, “younger Latino voters are building their political power, and voting maybe for the first time.” If the polls hold, most of those voters are going to support Sanders.

A solid majority of students in University of Texas professor Sean Theriault’s 150-odd class covering congressional procedure seemed to back Sanders. The few men and women I quickly canvassed all mentioned the candidate’s “integrity” and “authenticity,” along with the weight of health-care and college costs. These are the same kinds of explanations young people might give for a Sanders vote nearly anywhere else in the country—none had much to do with Texas specifically.

This sense of all politics becoming oddly delocalized extended to the municipal debates in Austin, which are jarringly Brooklyn or San Francisco-like. The faultlines are over land use, affordability, and especially growing homeless encampments, which the Austin City Council effectively decriminalized in much of the city in June. Like a notorious 2016 referendum that more or less banned Lyft and Uber, which the state government later overturned, the measure was evidence of Austin’s high threshold for progressive policy experimentation. Like the state and the country in general, the Texas capital is moving in two directions simultaneously, thriving while schisming, pulled between growing frustrations and the seeming impossibility of resolving core causes of discontent.

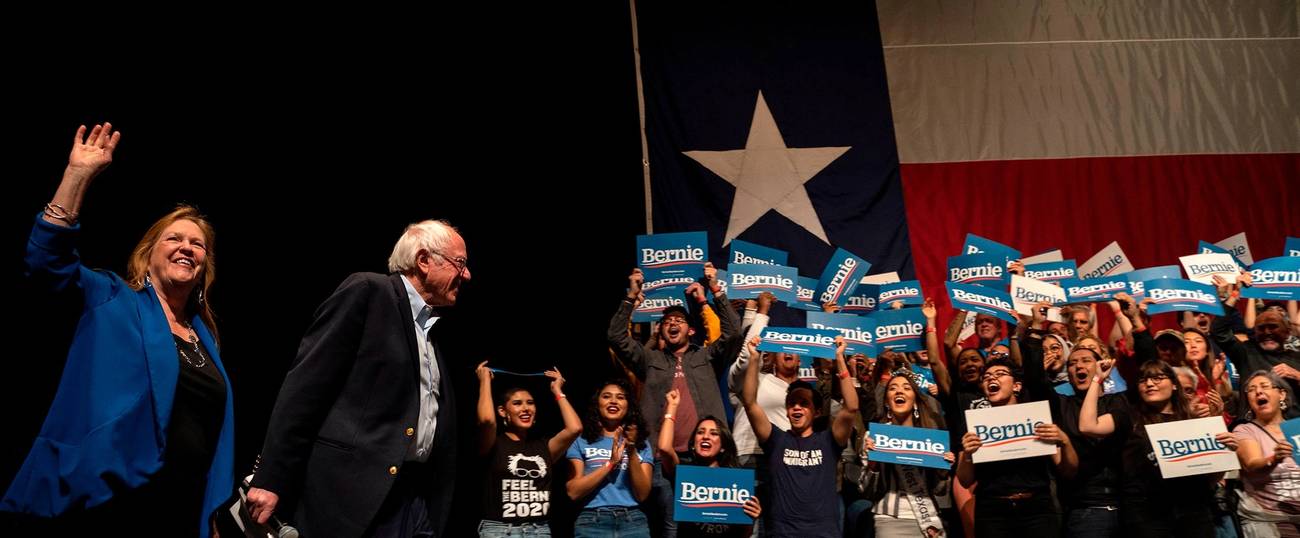

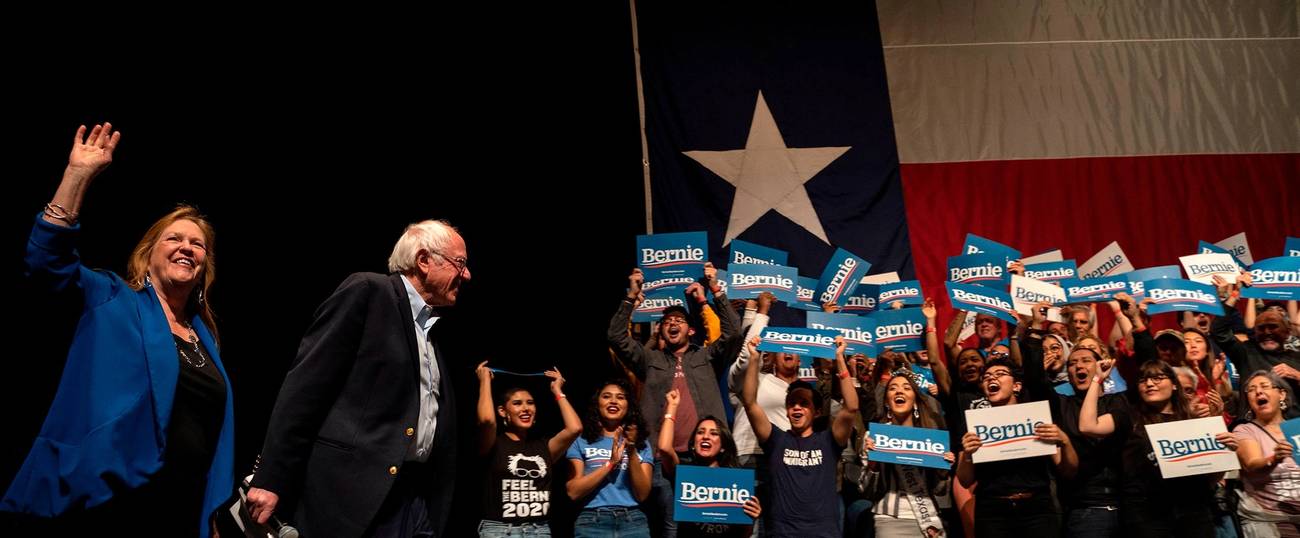

Little surprise, then, that Sanders drew 13,000 people to Auditorium Shores a few days before I arrived in town, a place practically in the shadow of the rainbow G crowning the cobalt Google high-rise on the opposite riverbank. Sanders was unambiguous proof that at least one person in power actually cared about the hopes and problems of the people in the crowd.

When the debate ended at Knomad, a small group toward the front of the bar began a round of “Solidarity Forever.” A dozen others joined, singing from memory even during the verses. The DSA’ers were pounding tables by the third verse, screaming at the words, “they have taken millions,” and “the ashes of the old.” Half the bar shouted the final chorus; the other half fell silent. “We’re gonna win!” someone exclaimed.

***

Read more of Tablet’s coverage of the 2020 presidential campaign here.

Armin Rosen is a staff writer for Tablet Magazine.