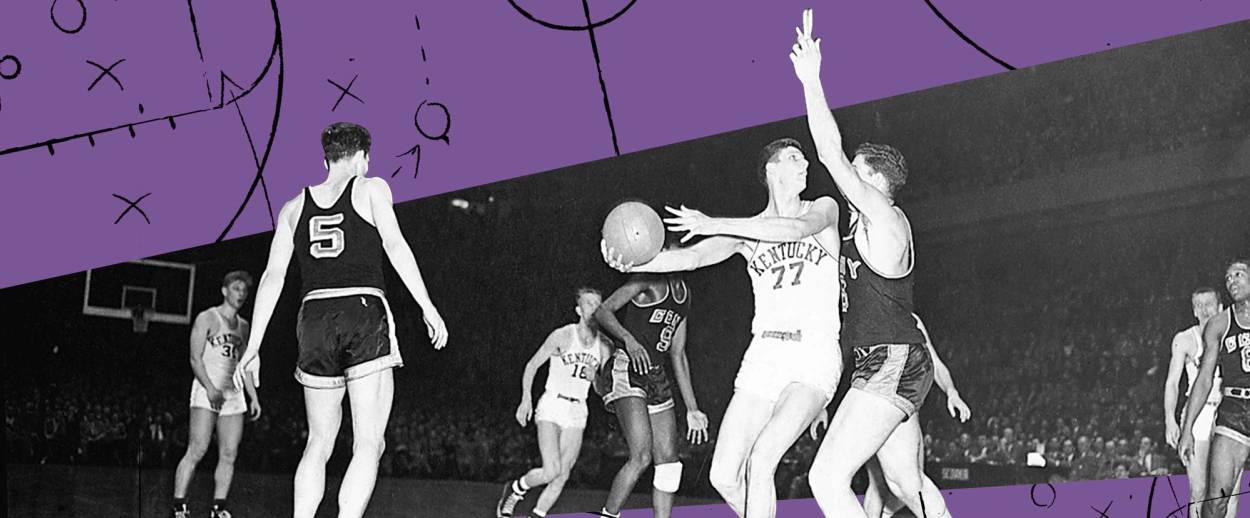

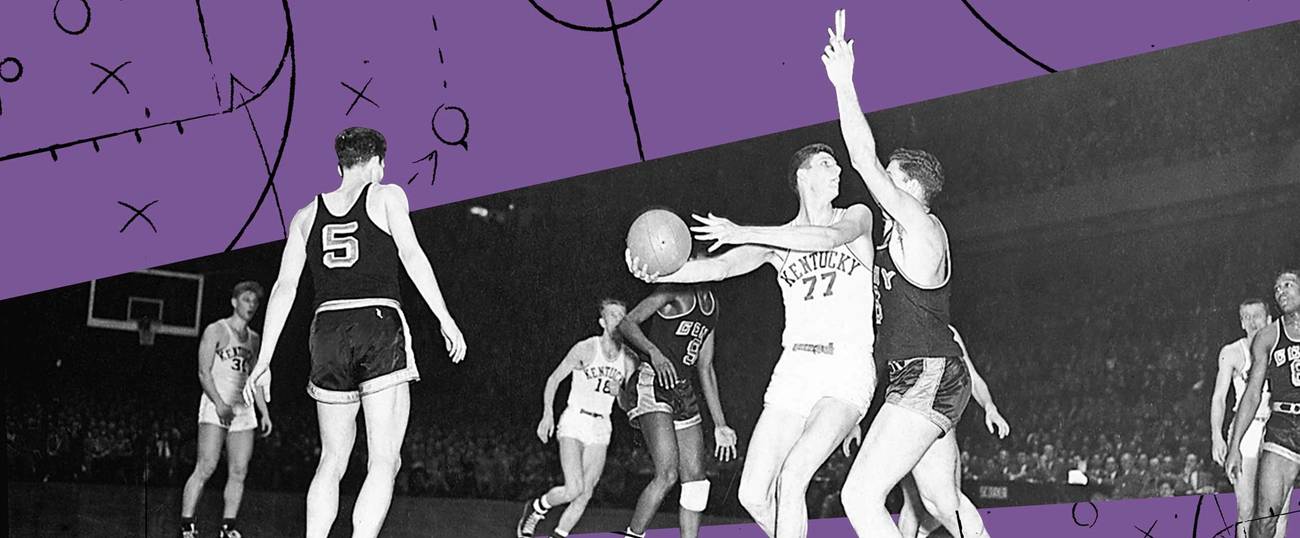

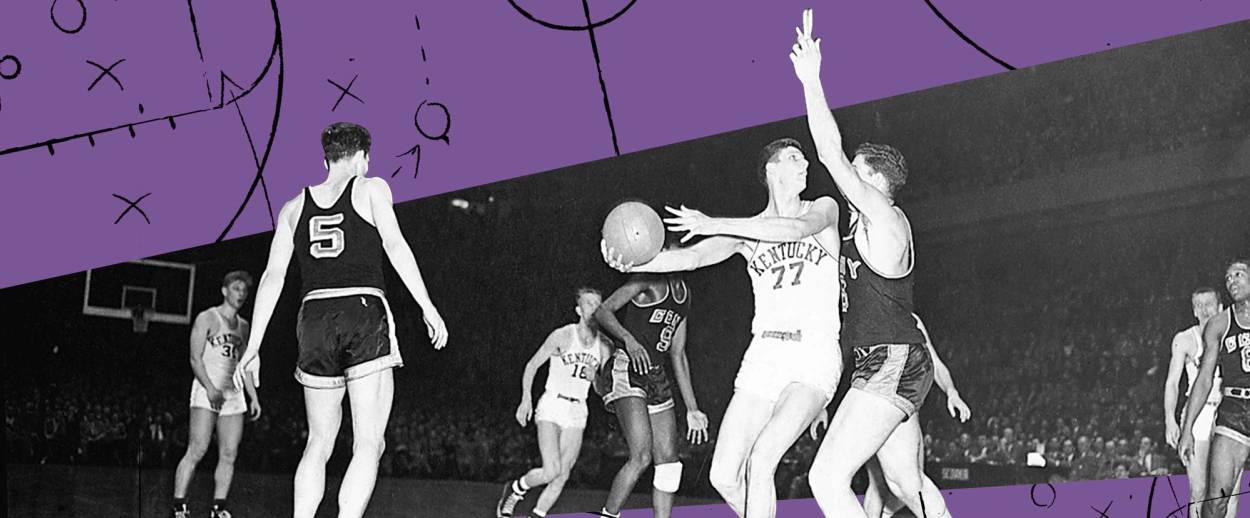

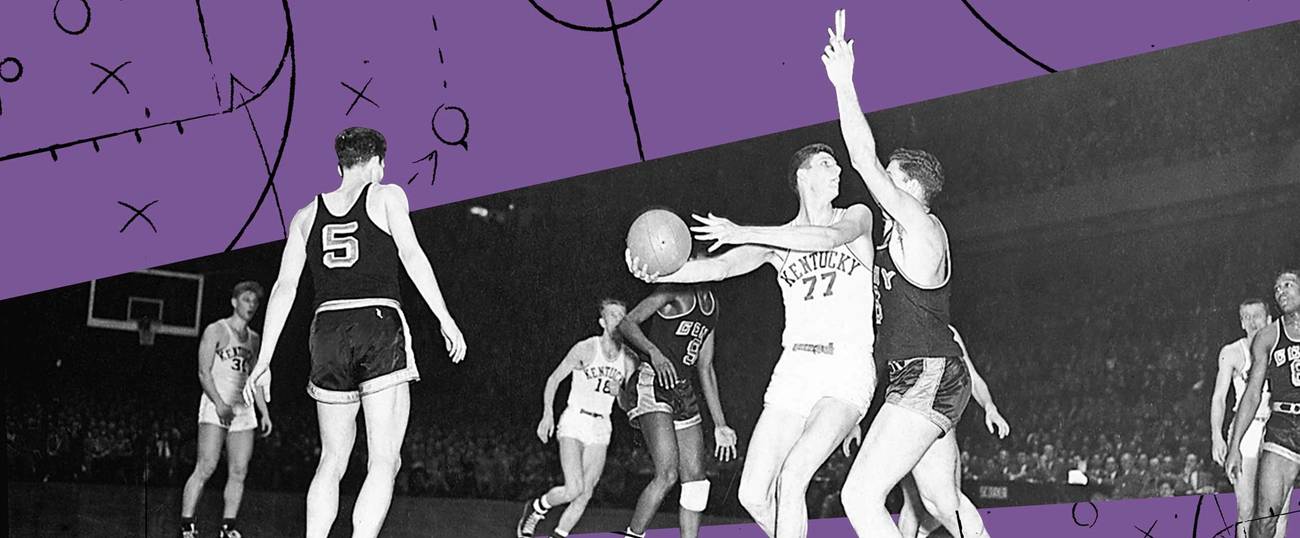

City College Routs Kentucky at the Garden in March Madness

Seventy years ago this weekend, an all-black-and-Jewish college basketball team crushed a racist opponent, on the way to a championship season for the ages

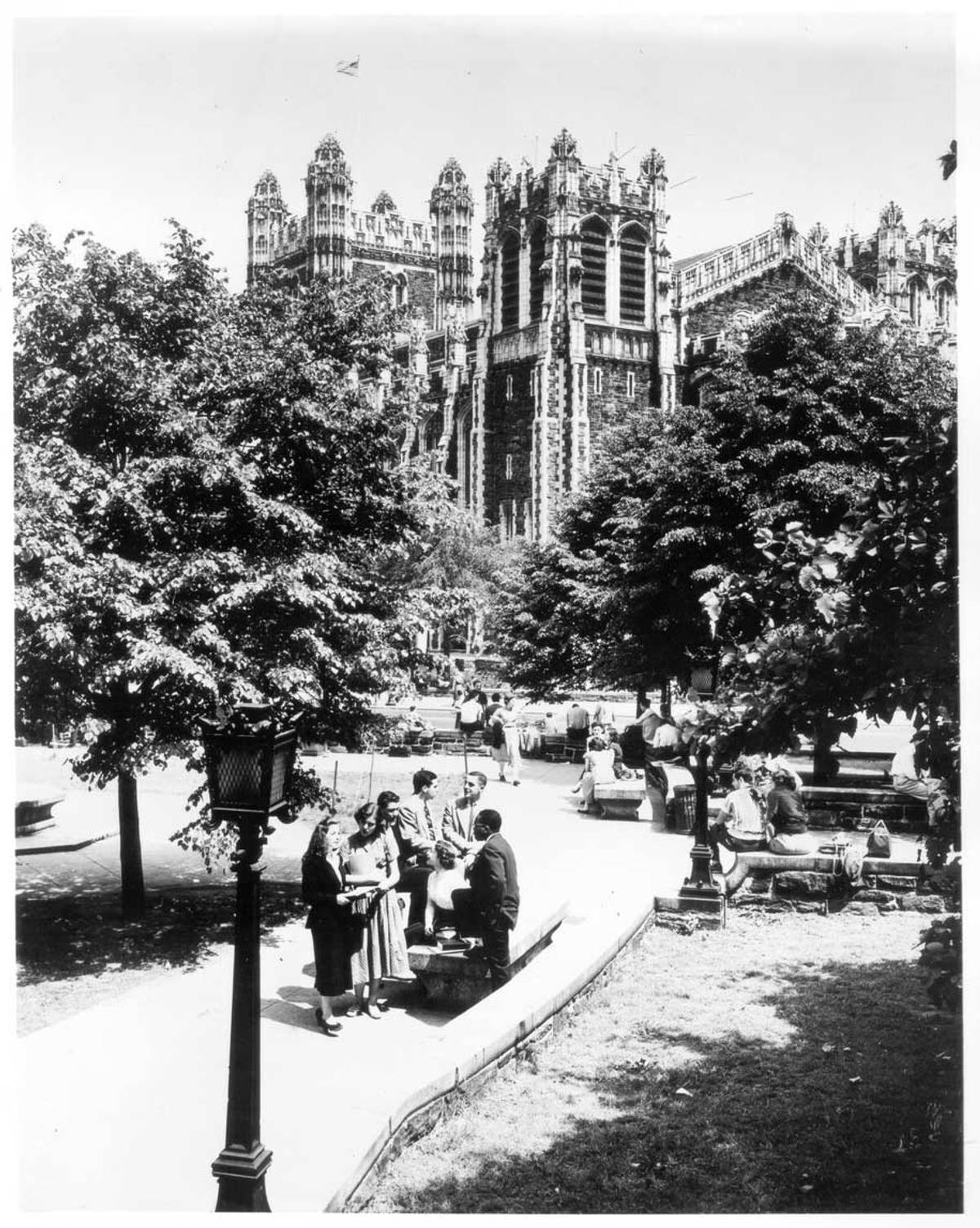

Exactly 70 years ago this month, the City College of New York stunned the world of college basketball by becoming the first—and still the only—team ever to win both the NIT and the NCAA tournaments in the same year. The 1949-50 Beavers were an extraordinary team, though, in more ways than one. They played not for a powerhouse state school but for a merit-based, tuition-free college known far more for intellectual achievement, and political engagement, than for athletic prowess. And only two years after Jackie Robinson integrated major league baseball, at a time when the newly formed NBA included not a single black player, every one of the 15 players on the City College team was either black or Jewish.

In conducting interviews for a book about that double-championship team, I found again and again that the tournament game the players and their fans remembered most vividly was not, as might be expected, one of the two title matchups. Rather, it was the NIT quarterfinal, played on March 14, 1950, against the University of Kentucky—a game that, for many of them, transcended basketball, in which the opponent seemed to be not just the elite team of the Old South, but the idea of segregation itself.

At the time, the Kentucky Wildcats were to college basketball what the New York Yankees were to major league baseball: the glamour team, the perennial favorite to win a championship. Over the previous six seasons Kentucky had won six straight Southeastern Conference titles, two NCAA championships, and an NIT championship. The 1948 Kentucky starting five had been selected for the U.S. Olympic team, which earned the basketball gold medal; after graduation an NBA franchise had been created expressly for them, the Indianapolis Olympians.

For much of the country, though, the Kentucky team was doubly iconic—both for its excellence on the basketball court and as a symbol of racial segregation. The team played for a college that among its 9,779 undergraduates had not a single black student; the graduate school had recently desegregated, but only under court order (in a case brought by a young NAACP attorney named Thurgood Marshall) and after enormous resistance: That summer the campus had been the site of seven cross-burnings.

The basketball team, of course, was segregated as well. Head coach Adolph Rupp had not permitted the Wildcats to take the floor against any team with black players until after World War II, when the integration of several top-flight Northern teams meant that maintaining the policy would effectively bar Kentucky from participation in postseason tournaments. This was only on the road, however; by 1950 no black player had yet appeared on Kentucky’s home court. Nor had Rupp himself been especially secretive about his racial views. Once, for instance, he was chatting with some New York sportswriters when the talk turned to the recent emergence of black players in the college game. “The Lord never meant for a white boy to play with a colored boy,” Rupp theologized, “else he wouldn’t have painted them different colors.”

More than 18,000 fans were in Madison Square Garden that March night, every seat taken and fans standing several deep along the rail at the top level. Shortly after 9 o’clock the teams ran onto the court and took their positions around the center-court circle; the City College players, two of them Jewish and three of them black, extended their hands to their Kentucky counterparts. The pregame handshake was a standard ritual, a simple gesture of sportsmanship, but this time three of the Wildcats turned away.

It was as though a lightning bolt, brief and unexpected and frightening, had pierced the arena, bringing a burst of intense illumination but leaving a foul smell in its wake. All through Madison Square Garden fans turned to one another for confirmation, not quite believing what they had seen. It was one thing to maintain an all-white team (indeed, several of New York’s top basketball programs, like NYU and St. John’s, had yet to integrate), but to refuse to shake hands with a black opponent seemed an affront, a kind of racial slur thrown before them, in their own house. Inside the Garden something changed in that moment. The atmosphere suddenly seemed to crackle with excitement and anger: The adjective used by everyone who was there that night, player and fan alike, was “electric.”

From almost the opening tip City College set a blistering pace. With each rebound the Beavers sped off down the court, the basketball ricocheting up and back and from side to side, from the rebounder who whipped a pass ahead to one of the wing men, who in turn sent the ball back to the other flank or flipped it over a shoulder to a trailer coming up the center. In the face of the relentless City College attack the Kentucky team looked slow, confused, overmatched. The Beavers scored 13 of the first 14 points; by the time a Wildcat sank the first Kentucky basket, nearly five minutes had elapsed.

That night City College forward Ed Warner seemed to be playing a different game from everyone else. At 6-foot-3 he was not especially tall, but he was strong, and his moves—honed in endless pickup games on the Colonel Young playground in Harlem—were quick and precise. At times he seemed to be moving in several directions at once, as though his hands and hips and head were operating independently; then he would abruptly dart left or right for a hook shot or slide toward the hoop for a layup. Sometimes, standing underneath the basket, he simply tossed the ball over his head, like a bride with a bouquet, banking it delicately into the net.

As the minutes passed the Beavers continued to build their lead. From the CCNY sections of the upper balcony came cries of “Charge!” and invocations of the unique City cheer, the “Allagaroo.” (“Allagaroo garoo gara!”) Near the end of the half someone was heard to call, “Pour it on, City!” and soon thousands of others had taken up the cry, “Pour it on, City! Pour it on, City!” while others chanted in counterpoint, “More, more, more! More, more, more!” while stamping their feet in rhythm, the floor vibrating so intensely that some of the fans began to worry that the balcony was going to collapse.

In the second half City College slowed the game down, and little by little Kentucky narrowed the margin. To the relief of the crowd the Beavers began attacking the basket once more, unleashing a stunning offensive display: In a span of two and a half minutes, City reeled off 16 consecutive points and the lead was never again threatened.

Ed Warner was not known for his outside shooting but this was a night when, it seemed, everything he tossed up found the basket, culminating in a miraculous 40-foot set shot just before head coach Nat Holman removed him with two minutes remaining. Warner had scored 26 points, and as he trotted off the court the crowd cheered and called his name over and over, even as play resumed; after the game Holman would call the ovation “the greatest ever given to a City player.” In the closing minutes someone in the City College section had the idea to launch into a rendition of “My Old Kentucky Home” as a kind of farewell to the visiting Wildcats, and he stood and began singing, “Oh the sun shines bright on my old Kentucky home,” and by the time he came to the chorus much of the upper balcony had joined in.

When the final buzzer sounded, the players on the City College bench stormed onto the court as though they had won the tournament; they hugged and clapped one another on the back as the fans stood and roared in astonishment and euphoria.

The final score was City College 89, Kentucky 50. It was the most lopsided defeat in Adolph Rupp’s career at the University of Kentucky.

The game had been the greatest sports triumph in the history of City College, but for those in attendance it could not help but seem even more significant—one student who was there told me that it felt “like something of a revolution.” Almost from its inception the mission of City College had been to welcome the poor, talented young people of New York, children of pushcart peddlers and garment workers and washerwomen, and help them to move from the margins into the mainstream of American society. This victory seemed of a piece with that: an assertion by Jews and African Americans, historical outsiders, of their right to inclusion, and in its way, a blow struck against the narrow-mindedness and bigotry that, for many of New York’s basketball fans, had come to be personified by Kentucky head coach Adolph Rupp.

The Beavers would go on to win two more games in the NIT tournament, defeating the top-ranked Braves of Bradley University on March 18 to win the championship. Ten days later, CCNY again defeated Bradley to take the NCAA title, and with it the so-called Grand Slam.

The elation of the double championship, though, would be tragically short-lived: The following year the team’s top seven players were arrested and confessed to taking money from gamblers to shave points in several regular-season games. The players were thrown out of school and banned for life from the NBA; Ed Warner, one of the few African American players caught up in the scandal, was sent to prison.

The players who were involved lived for years in the shadow of that scandal. For them and their teammates, however, and for so many of their fans, scandal could not erase, nor time dim, the memory of their achievements on the court, in particular that astonishing game when the team seemed to embody most perfectly the city’s own brightest hopes for itself. The night after the Kentucky game, Nat Holman celebrated the victory by taking his players to see South Pacific on Broadway. Just before the house lights dimmed, the public address announcer came on the speakers to introduce the team, and the audience stood and gave them an uproarious ovation. “At that moment,” one of the players recalled decades later, “it seemed like we all could have run for president.”

***

Adapted from The City Game: Triumph, Scandal, and a Legendary Basketball Team, by Matthew Goodman. Copyright © 2019 by Matthew Goodman. Published by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Matthew Goodman is the author of four books, most recently,The City Game: Triumph, Scandal, and a Legendary Basketball Team.