Lost in Translation

A Ramallah man struggles to find a reading public for Maimonides

When Mohammad Husein studied at Hebrew College in Boston, he was delighted to put to use his years learning Hebrew in Ramallah. As a Master’s student (class of 2007), he often went to Saturday morning services and helped his neighbors find their way in Hebrew prayer books. But once he returned to the West Bank, Husein, 54, found far less use for his professional interest in Judaism. A year after translating into Arabic an abridged version of the code of Jewish law known as the Mishneh Torah, written by the medieval philosopher Moses Maimonides, Husein said he can only find work as a truck driver. His story reflects the difficult position of Arab Muslim scholars who wish to learn about Jews.

Born in Jerusalem to Palestinian refugee parents from Abu Shusha (today’s Kibbutz Gezer, not far from the city of Ramla in central Israel), Husein remembers throwing stones at the Jews who passed through a gate in the barbed wire that split East Jerusalem, where he grew up, from the rest of the city. The wire came down when Israel conquered East Jerusalem in 1967, and Husein met his first Jewish friends. A decade later, he studied psychology and sociology at Bethlehem University. As Husein read Marx, Trotsky, and Rosa Luxemburg, he realized the writers were all Jews. He resolved to learn Hebrew to better understand the Jewish people. By day, he chatted with his Israeli coworkers in a cement factory. At night he read the Bible, first in Arabic—“We were fortunate the Christian Arabs translated it to Arabic,” he said—and then in Hebrew.

Husein sidelined his hobby to raise three children, Khalil, Dalila, and Majd. But about 15 years ago he remembered the Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides, about whom he had heard a few sentences in high school in Ramallah.

“Maimonides wrote his books in Hebrew letters but in Arabic words,” said Husein. “I discovered I could read Maimonides in his original language. How many Jews can do that?”

Husein, a non-practicing Muslim, said he studied the Jewish people to promote peace and explore his own history.

“The people of Palestine did not all come from Arabia,” he said. “There were people before them, Jews and Christians. Some left, the majority stayed. I don’t consider myself a Jew or Hebrew or Israelite. I’m Arab. But all those people before and after Islam, I consider my ancestors.”

The Rambam, as Maimonides is known, provided an inspiring example of living in multiple worlds. He was born in Córdoba, Spain, in 1135 at a time when Jewish poets modeled their work on Arabic verse. A decade later, Maimonides and his family fled Córdoba to escape death or conversion forced by the invading Islamic Almohades army. Rather than running to Western Europe, Maimonides moved to Morocco and then Egypt. In Fustat, near Cairo, Maimonides was court physician to Sultan Saladdin. As a philosopher, Maimonides worked with his Muslim contemporary Averroes on advancing the writings of Aristotle. But he was also the spiritual leader of Fustat’s Jewish community, and he penned the authoritative codification of the oral tradition, the 14-volume Mishneh Torah. Maimonides died in Egypt in 1204 and was buried in Tiberias, Israel.

“During the very critical period of history—the Crusades—it was a Jew who treated Saladdin himself,” Husein said. “It means the Muslims trusted the Jews a lot.”

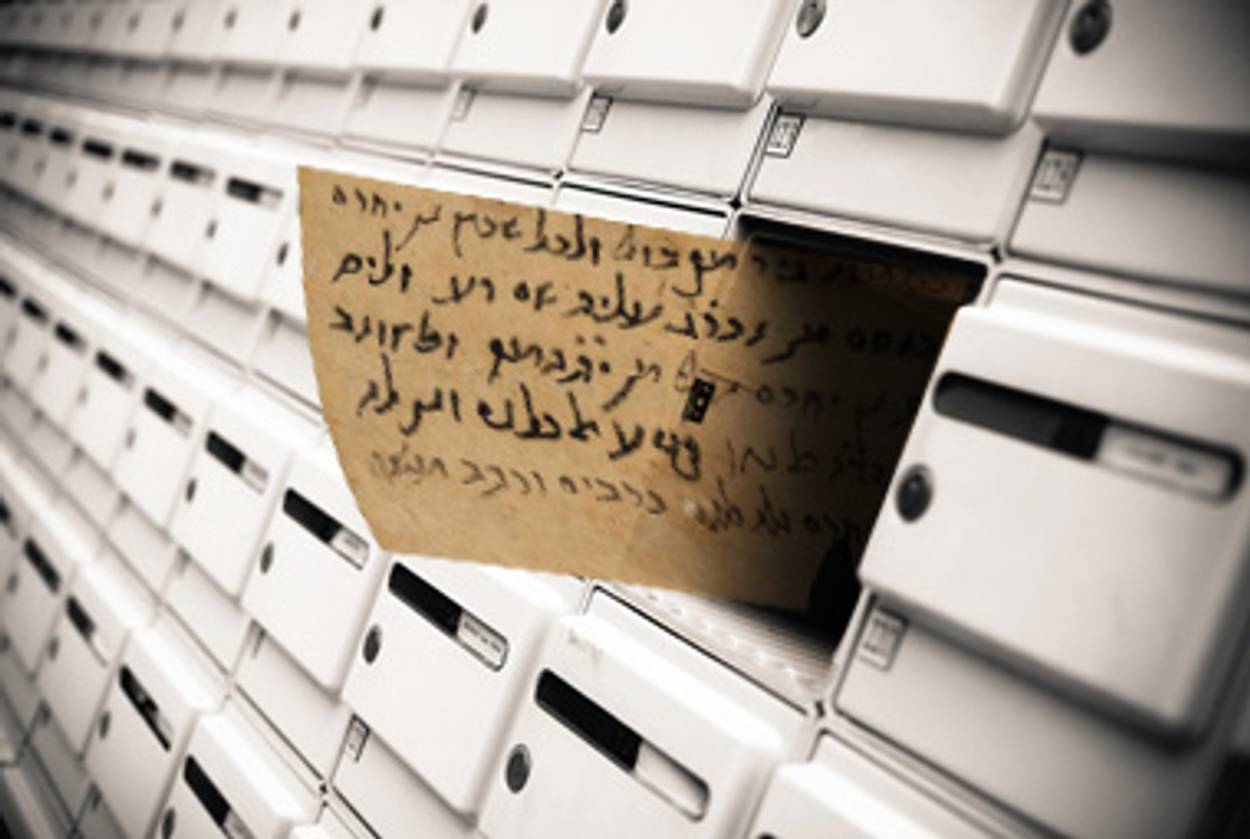

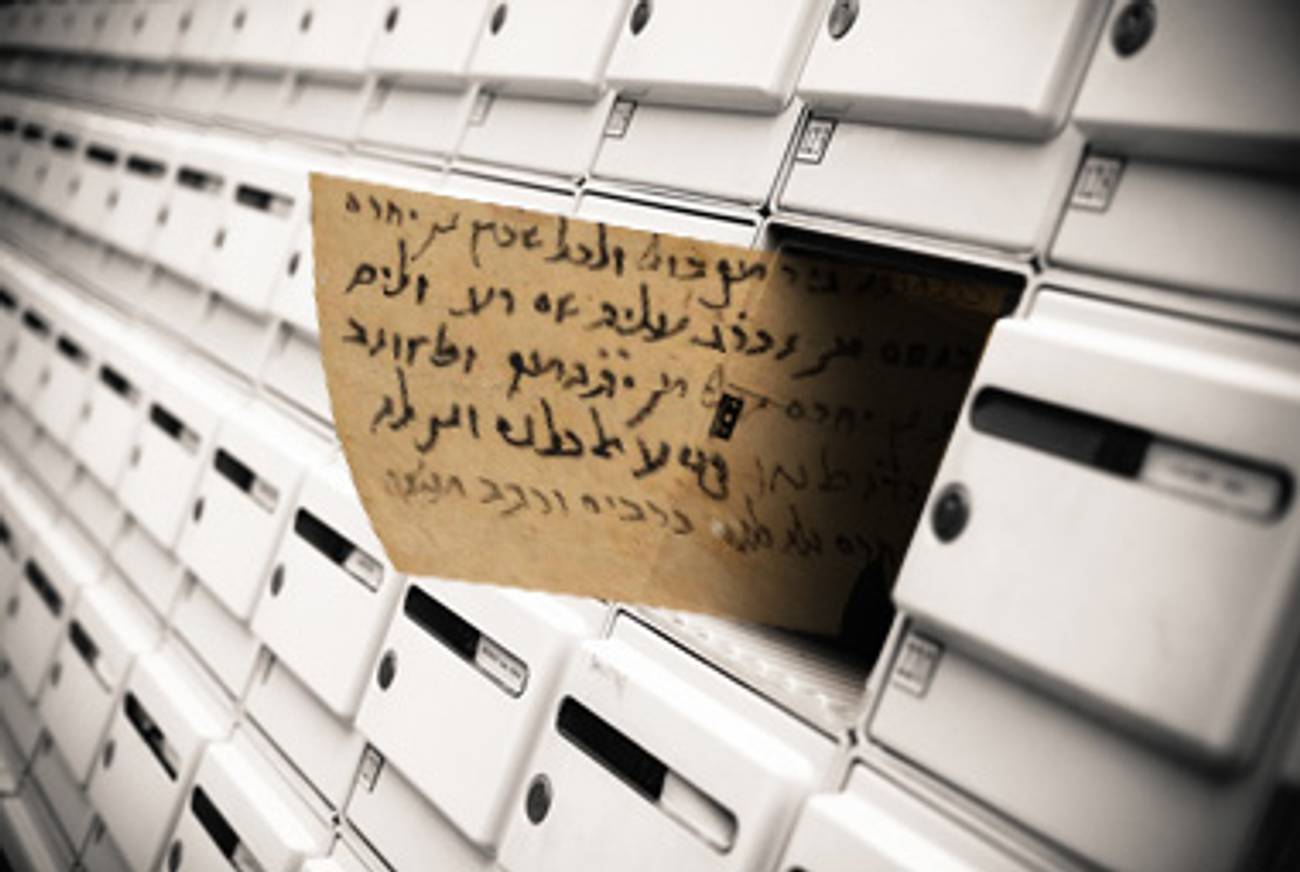

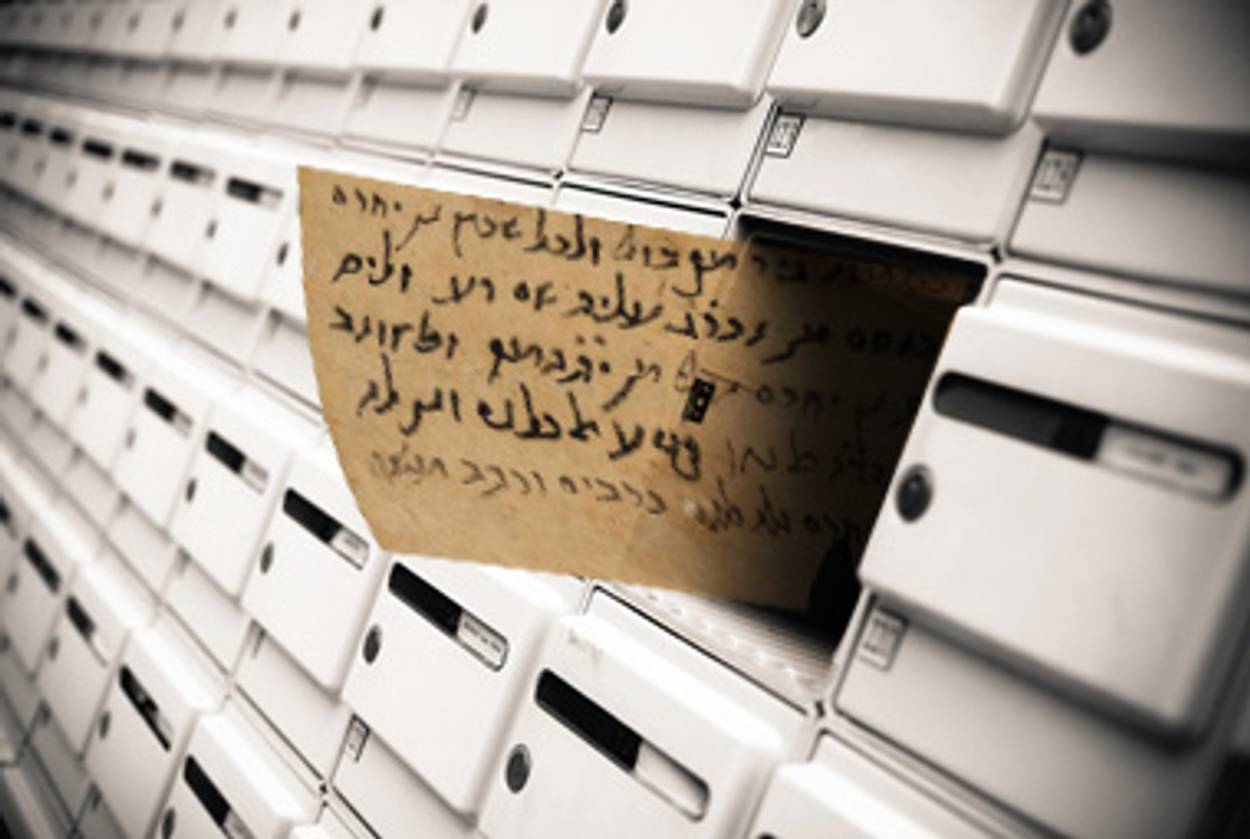

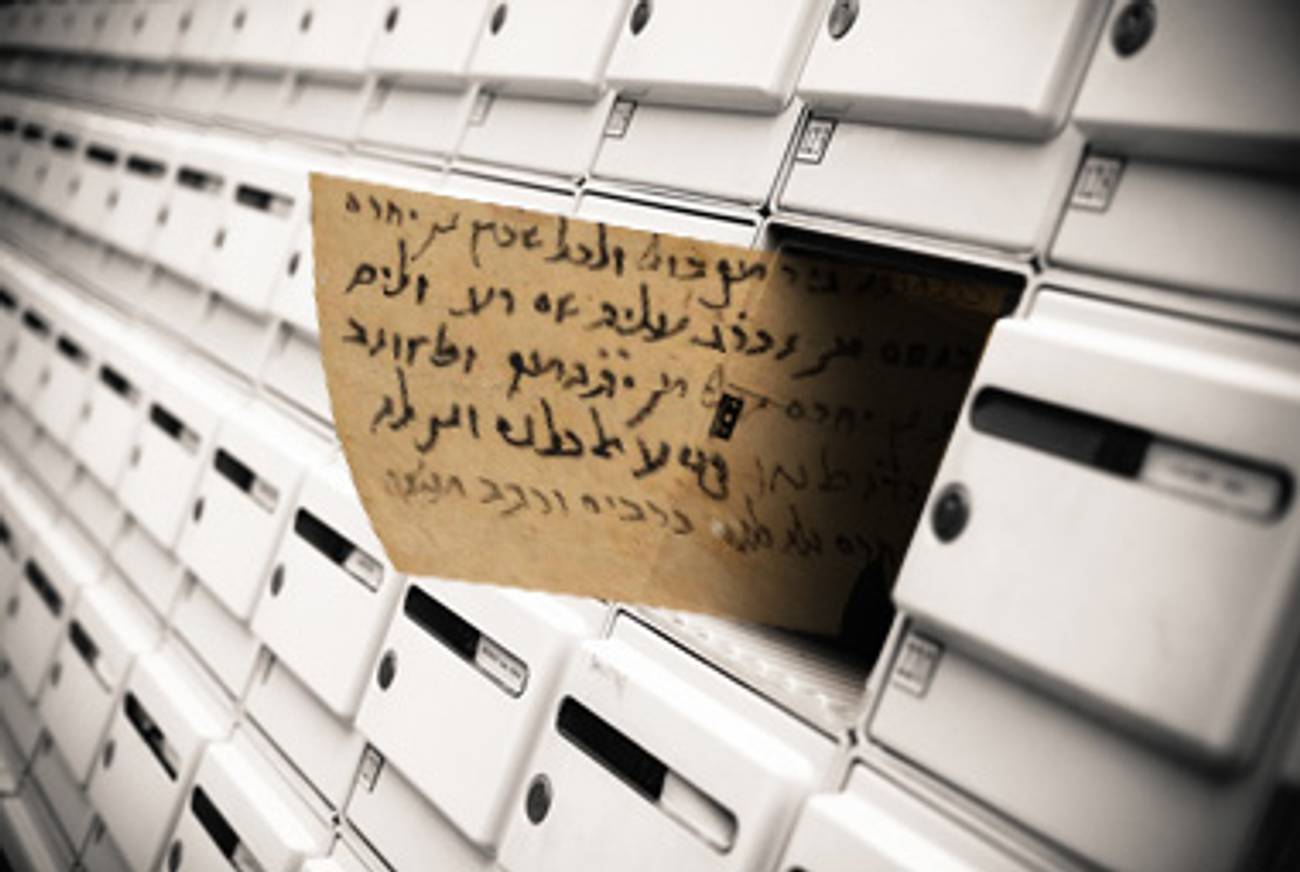

In 2002, Husein contacted Nathan Ehrlich, then dean of online studies at Hebrew College in Boston. In a meeting at Jerusalem’s King David Hotel, the two realized they were both born in the capital on the same date in 1954. Husein studied by correspondence for two semesters and then got a scholarship to study on campus for his second year. Before he left Boston, Husein bought the abridged Hebrew Mishneh Torah in a discount bin. Unlike Maimonides’ other works, which were written in Judeo-Arabic, the Mishneh Torah was composed in Hebrew.

“I read some pages and said this must be translated because Arabs know nothing about it,” he said. “They know nothing about Jewish thought. We are fortunate to have a book like this that summarizes 14 books.”

Husein translated the book into Arabic on the white plastic table on his balcony, just steps from the official residence of Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas. To support himself, Husein taught Hebrew part-time at the Ramallah YMCA, and his wife worked in the library of the nearby town of El-Bireh.

The work done, in 2009 Husein called publishers in Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, and Jordan. He sent query letters to Palestinian universities and Israeli research institutes. No one was interested. He chalked it up to the content. Arab readers, he said, are hungry for military tales, the biography of Israeli nuclear whistle-blower Mordechai Vanunu, or the life stories of Zionist leaders like Theodor Herzl, Menachem Begin, and Golda Meir. Hebrew literature has also found Arab readers; this year, a translation of Amos Oz’s memoir A Tale of Love and Darkness was published in Lebanon.

Publishing Maimonides in Arabic would break that mold by bringing the spiritual foundations of Judaism to an Arab audience, but his book was nearly a thousand years old. Husein said he also translated Martin Buber’s 1956 Hasidism and Modern Man, to offer a more modern work, but no one has bitten on that one either.

In the West Bank, Birzeit University’s philosophy and cultural studies department teaches survey courses on European civilization and thought, but it gives short shrift to Semitic philosophy of any kind. “We have two Islamic philosophy professors here, and they don’t give courses themselves,” said Nadim Mseis, a lecturer in the department.

In the East Jerusalem village of Abu Dis, Al-Quds University has run an Israel Studies program for a decade, where Palestinian students learn the roots of modern Zionism. But the department has little use for a Jewish theological tract. Uri Davis, born in Kfar Shmaryahu in Mandatory Palestine in 1943, is the only Jewish member of Fatah’s Revolutionary Council.

“In the shadow of 60 years of occupation, it is rather complicated to establish Jewish studies,” Davis said in a Ramallah meeting. “It’s not a question of lack of interest. You have to defeat apartheid in Israel and remove the occupation before you can even begin to negotiate that kind of study.”

Rachella Mizrachi, of Tel Aviv, lectures at Al-Quds in Arabic about what she terms the “experience of Jews from the Islamic world in Occupied Palestine.” While she mentions the Rambam, Mizrachi said, she focuses on the devastation of those Jewish communities of the Islamic world in the 1950s.

“The destruction of the Arab Jewish communities is another result of the Zionist project,” she said. Asked how her students react, she said, “They understand that the same man who destroyed our culture is the same ethnic group that is destroying their culture.”

Husein’s difficulty doesn’t surprise Mohamed Hawary, a professor of Jewish thought and comparative religions in Cairo’s Ain Shams University. Hawary wrote in an e-mail that an Arabic translation of the six books of the Mishnah were published between 2006 and 2009 but that no one has tackled Maimonides yet.

“Here in Egypt, all of us scholars dealing with Hebrew and Jewish studies are suffering when we want to publish a book,” he wrote. “I think that Mr. Husein can find a Jewish publisher or Jewish center or institution in Israel who believes how it is important to spread Jewish culture.”

Yet Israel has proven to be equally unfertile ground. The Institute for the Translation of Hebrew Literature, based in the Tel Aviv suburb of Bnei Brak, only deals in modern fiction. Tel Aviv’s Moshe Dayan Center for Arab-Jewish Studies focuses on history and politics. At the Jerusalem Minerva Institute, which teaches Arabic to Israelis, director Assaf Golani suggested he could publish the translation, provided Husein does not expect to get paid. At press time he was still examining a sample of Husein’s work.

One option may lie with Intellectual Encounters, a virtual academic community of scholars who study the medieval world of Islam. On the steering committee are Hebrew University rector Sarah Stroumsa, Yale Islamic studies professor Frank Griffel, and Sari Nusseibeh, who is president of Al-Quds University but working on this project privately as an Islamic philosophy scholar. Funding is from the Rothschild Family’s Yad Hanadiv Foundation in Jerusalem.

Academic director Raquel Ukeles said the program will include a course on medieval Islam to be taught at Yale, Al-Quds, Bar Ilan University in Israel, and Tübingen University in Germany. Further, the program’s website will publish translations of important works, and scholars who speak Hebrew and Arabic would be useful. Ukeles, who has traveled to Egypt, Morocco, and Qatar, said, “Everywhere I go people ask me, ‘Can you recommend books about Jewish philosophy?’ ”

“Now that I know about Husein, and if he’s doing good work, I think I can work with him to raise money,” she said.

In 2007, Husein told Hebrew College Today that he wanted to work in Ramallah as a professor or for an organization that advanced the cause of peace. But three years later, the Mishneh Torah has turned into an albatross that has even strained his marriage, he said. He dreams of earning a doctorate in Holocaust or Jewish Studies but has not applied for a Fulbright scholarship that could cover the costs. He needs a job but can’t find one. For now, he has Hebrew teaching gigs from time to time and passes his days reading about the Holocaust on his balcony.

“I am working without any purpose,” he said. “A man lifting stones from place to place.”

Daniella Cheslow is a Jerusalem-based journalist.

Daniella Cheslow is an American journalist covering the Middle East.

Daniella Cheslow is an American journalist covering the Middle East.