Hannah Arendt’s Draft of History

The edited typescript of “Eichmann in Jerusalem” reveals New Yorker editor William Shawn’s meticulous work

On April 15, 1962, Hannah Arendt sent a brief personal note to William Shawn, the editor of The New Yorker, thanking him for some flowers he had sent. It had been a rough winter for the political philosopher: Her husband, Heinrich Blücher, was suffering from a brain aneurysm, and Arendt had developed a severe allergic reaction to antibiotics she was given to treat a cold. Then, in March, a truck had plowed into a taxi she was taking through Central Park, resulting in a concussion, hemorrhages in both eyes, broken teeth, and fractured ribs. Nevertheless, in her note three weeks later to Shawn—who had assigned her to cover the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem a year before, and was still awaiting her copy—Arendt sounded almost chirpy. “I am much better,” she wrote, in her blue-ballpoint cursive, spidery and cramped on cream-colored stationery, “and on the point of going back to work.”

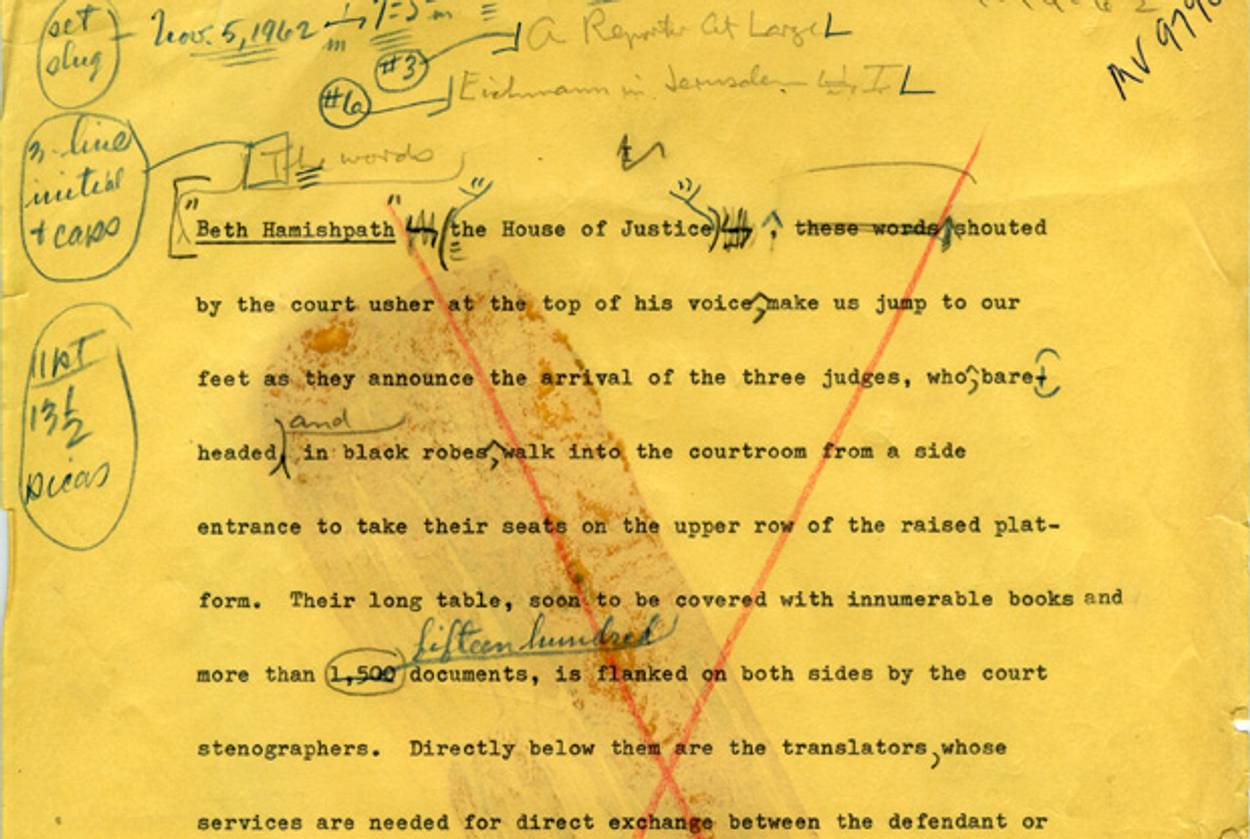

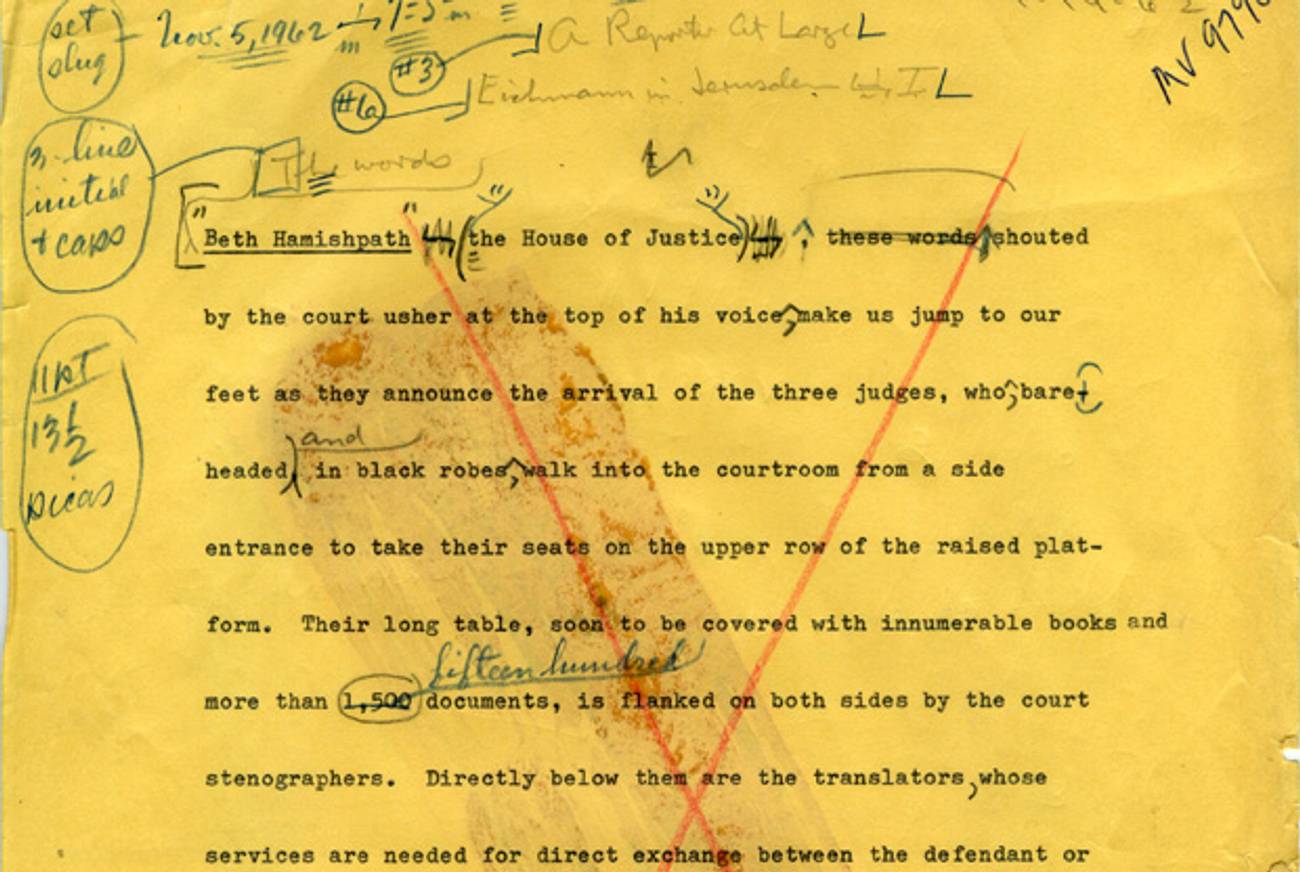

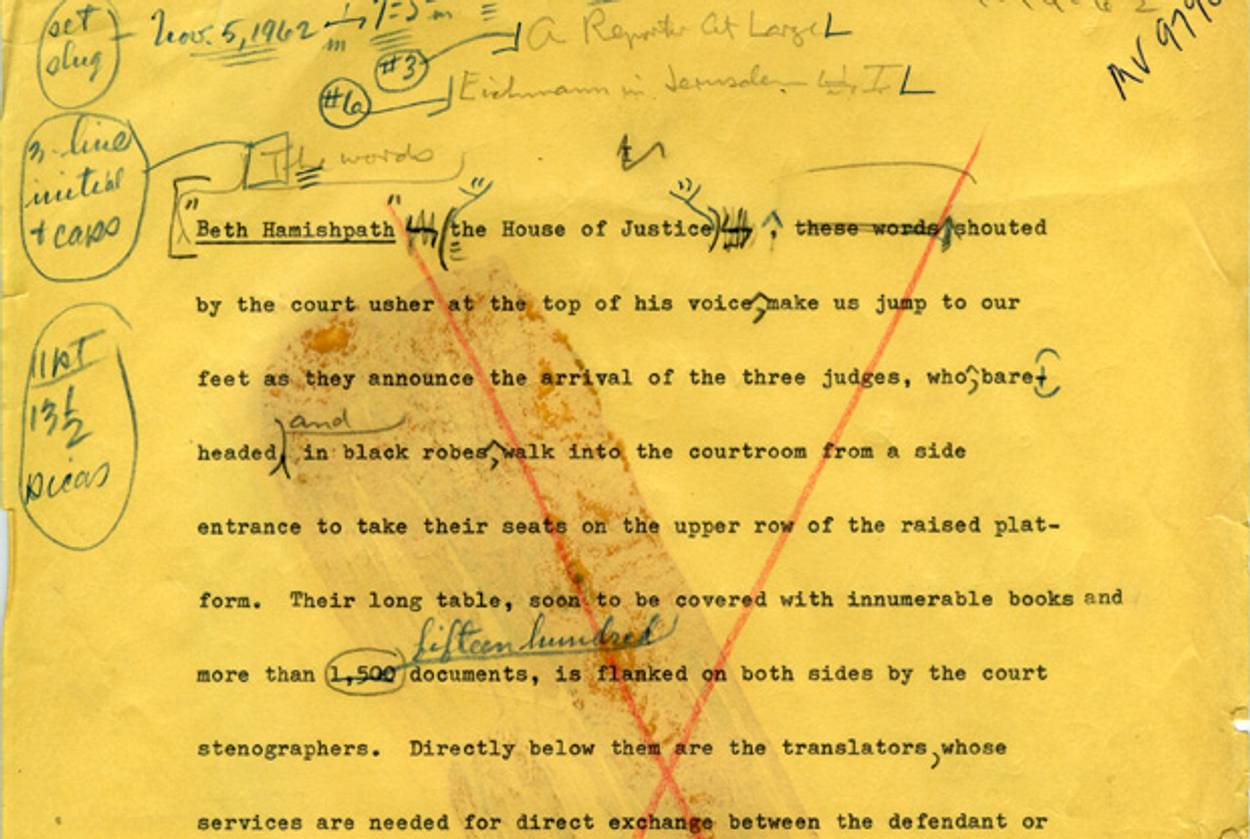

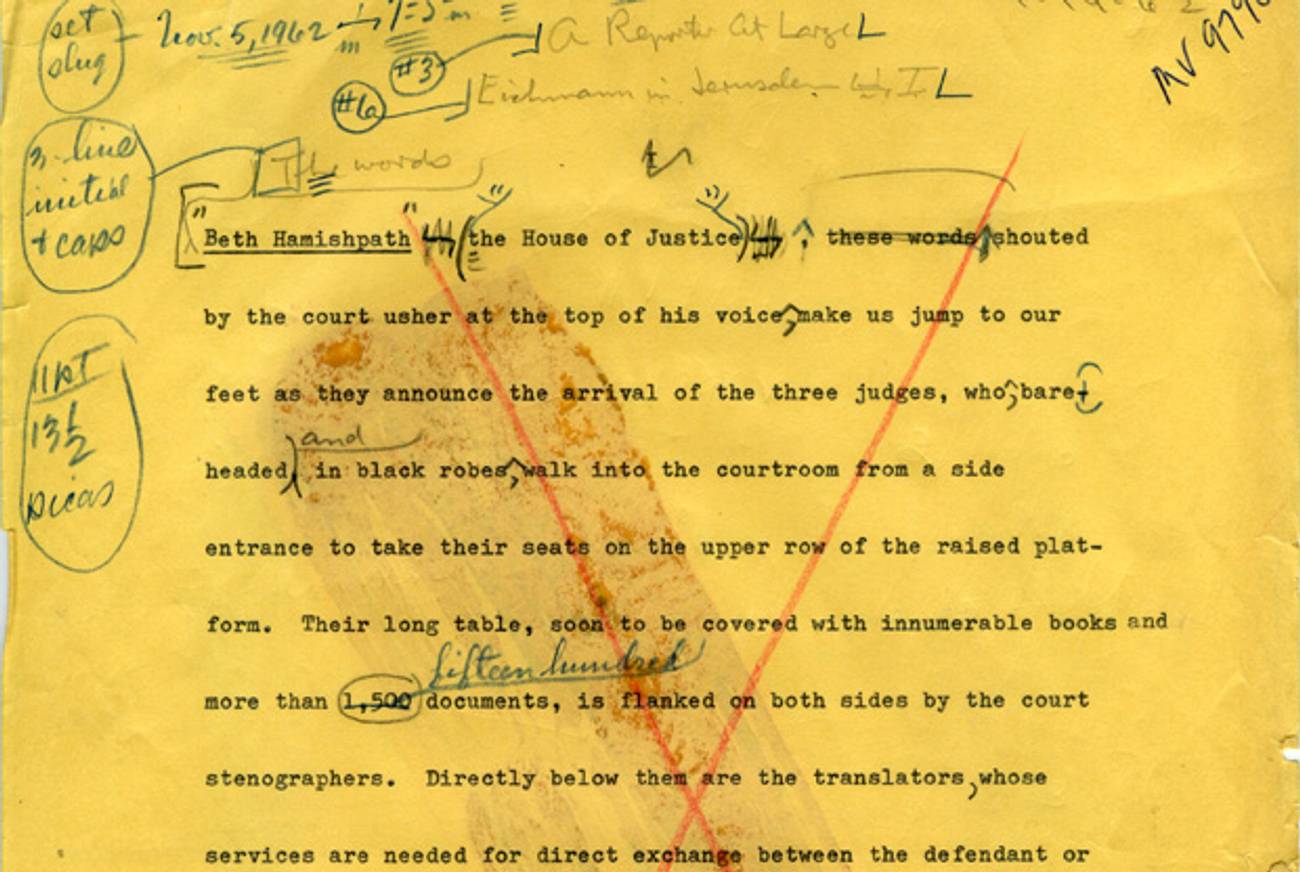

Five months later, she was done. On Sept. 19, a sheaf of onion-skin pages arrived at The New Yorker’s office at 25 West 43rd Street, with the title, “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report.” The manuscript was sent over to the typing pool, where it was copied onto heavy yellow bond, double-spaced, and then returned to Shawn for editing.

Meanwhile, a carbon copy was delivered to Arendt’s publisher, Viking Press. A lightly edited version of her manuscript was published as a book in May 1963 under the same title she’d picked for the New Yorker articles that were published in February and March but with the dramatically enhanced subtitle “A Report on the Banality of Evil.” The book, with revisions, has remained in print since. But it never reflected Shawn’s changes to Arendt’s draft, which was serialized in five issues of the magazine. So while The New Yorker remains almost reflexively associated with “Eichmann in Jerusalem,” the text that most people have in mind when they talk about Arendt’s report is not, in fact, the one that appeared in the magazine.

The Shawn typescript, cluttered with pencil marks, is now held with the rest of The New Yorker archive at the Manuscripts and Archives Division of the New York Public Library. His major cuts and alterations to Arendt’s original are striking in their consistency: Almost all of them involve Arendt’s asides about the contemporary Jewish community and its handling of the trial. Many of the most controversial passages made it into the magazine intact, including her assertion that “if the Jewish people had really been unorganized and leaderless, there would have been chaos and plenty of misery but the total number of victims would hardly have been between five and six million people.” But the final magazine text is in some ways less provocative, more streamlined, and—unsurprisingly, given the precision of The New Yorker’s legendary copy editor Eleanor Gould—more polished than what’s in the book.

In one sense, Shawn was simply exercising his preference for straightforward structure and well-modulated language: The sections cut from the magazine, especially near the beginning, are generally asides that distract the reader from the central focus of the Eichmann narrative. In some places, he reined Arendt in, softening her claim that Hitler was, in 1935, “admired everywhere as a great national statesman” with a judiciously placed “almost” before “everywhere.” But the cuts also reflect Shawn’s aversion to what Irving Howe, in his criticism of Arendt in Commentary, self-deprecatingly described as the “grubby” polemic of the little intellectual journals. (Ben Yagoda, in his New Yorker chronicle, About Town, noted that Arendt went to Shawn for the assignment on the advice of her friend Mary McCarthy only after Norman Podhoretz told her Commentary couldn’t afford to send her to Jerusalem; given that Podhoretz responded to Arendt’s finished piece with a scathing review subtitled “A Study in the Perversity of Brilliance,” one can only imagine that the final product would have been quite different had Arendt been writing for him.)

Arendt doesn’t appear to have fussed over the cuts. “She did not like to look at things, or go back to things,” explained Jerome Kohn, Arendt’s former research assistant and now her literary executor. “What she gave to Shawn she left in his hands, and what she sent to the publisher, she left in theirs.” She did, however, send in corrections, and requested multiple sets of galleys during editing. “It would make things easier for me,” she wrote to Shawn on Sept. 30, 1962. After the first installment of the series was published, the following February, she wrote to chastise Shawn for an error she had found in the text concerning the date of Yad Vashem’s establishment. “This is an error,” Arendt wrote, noting she had spoken to the fact-checker, William Honan, who went on to be a culture editor at the New York Times. “This is not very important but it confirms my conviction that no dates or facts provided by your checking department should be inserted unless they are checked and approved by me.”

The date of Yad Vashem’s founding turned out to be the least of it, of course. According to Arendt’s biographer Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, Shawn cabled Arendt on March 8 to advise her of the response to her piece: “People in town seem to be discussing little else.” A few days later, on March 13, she replied that she had begun receiving angry letters. “Now the Jews know that enemy No. 1 is not ‘the German’ and the Germans agree that enemy No. 1 is not ‘the Jew,’ it is me,” Arendt wrote, in a letter held at the Library of Congress. “This, to be sure, is an exaggeration and your checking department would not let me get away with it.”

Allison Hoffman is a senior editor at Tablet Magazine. Her Twitter feed is @allisont_dc.