A Teacher’s Perspective on the Chicago Strike

What the legacy of the Chicago strike should be

As a New York City public school teacher, I viewed last week’s Chicago teachers strike–which ended last night–not as an argument with a clear “right” or “wrong,” so much as an indicator of the overall brokenness of the American education system. Teachers struck because they face woefully inadequate working conditions, including over-sized class rosters, non-functioning heating and air-conditioning systems, limited or non-existent support from parents and administrators, and low pay. But perhaps the biggest point of contention: the threat of professional evaluations being tethered to students’ scores on standardized tests whose results, many feel, penalize those who teach students with the highest needs.

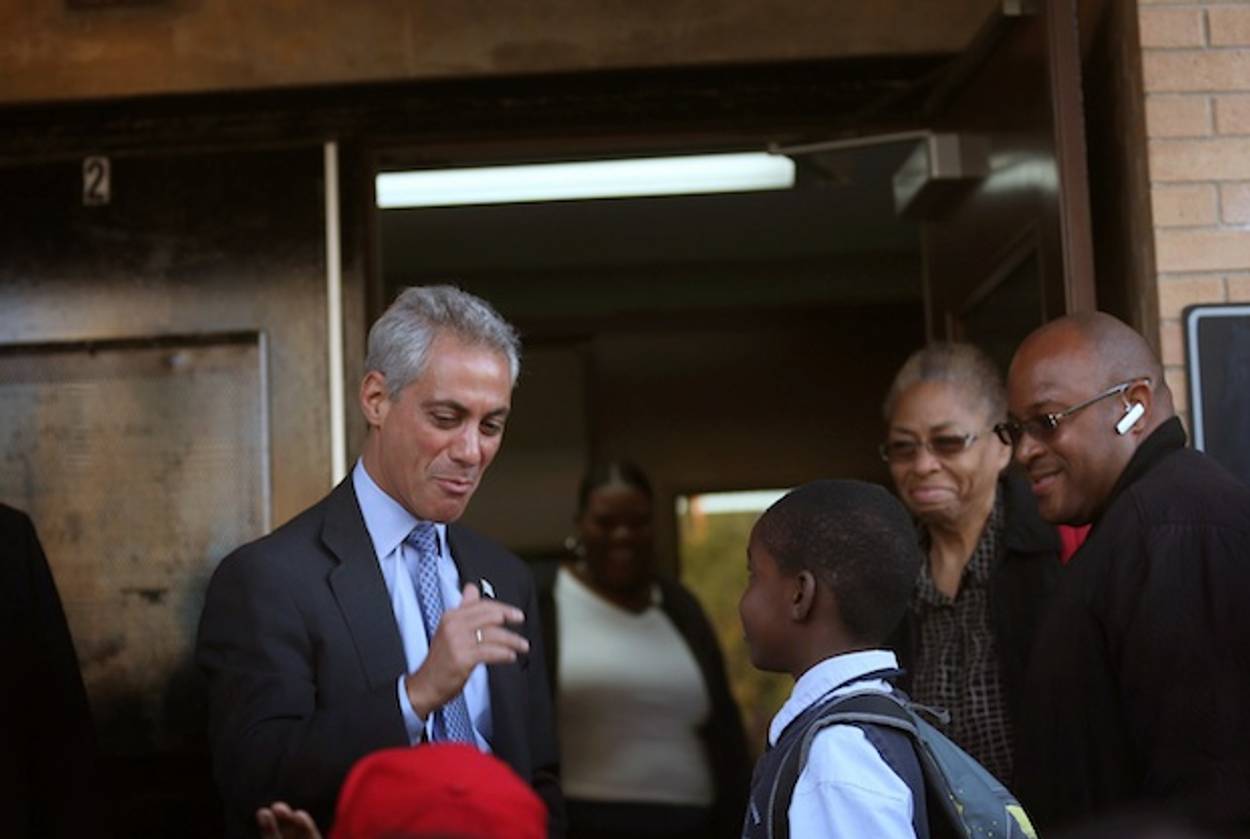

The Chicago Public School board and Mayor Rahm Emanuel, for their part, want meaningful ways to assess teacher performance, which include standardized tests, and the ability to more easily dismiss underperforming teachers who, it is commonly felt, are rendered untouchable due to teachers union protection. They also seek to make their funding model (including everything from day-to-day operating costs to teacher pension plans) sustainable and provide more instructional time over the course of the year.

None of these concerns is invalid; however, harping on any one at the exclusion of the others is misguided. Too often in the education debate, we see a reductive approach: as though, say, agreeing to use standardized tests as a component of teacher evaluations, or conversely, doing away with them entirely, would suddenly solve everything. It’s not all about tests, teacher quality, funding, or any one thing alone.

It’s tempting for me, as a Bronx teacher, to offer my own work day as a sort of object lesson in institutional failure: In one of my classes, I have 47 students on the roster. Though I’m assured everything will be equalized such that none of my five classes has more than 33 students, I am anxious about finding enough time to connect with 165 10th graders of widely varying abilities, comment in a detailed way on all their writing, follow up with each of them to see that they comprehend the reading, and give assignments that aren’t “busywork.” The type of instruction most of these students need is intensive, and I’m spread thin. Every year I have to scramble to find, borrow, or steal enough books so that each student can do the assigned reading. To top it off, the Xerox machine is perpetually broken, so copies are rationed–and sometimes you need to give 165 kids a poem, a quiz, or a graphic organizer.

And yet, though these conditions exist in far too many urban classrooms, my daily experiences don’t represent the sum total of what’s wrong with education. Nor are the solutions I’d advocate for, such as more and better materials and increased funding at the state level in order hire more teachers and relieve the bloating of class sizes–enough that, were they implemented, everything would be “fixed.” Every aspect of the conflict, from funding issues, to teacher evaluations, to teacher training and retention, to the culture of diminishing respect for education, needs its own set of solutions, even its own government task force, perhaps.

“We could not solve all the problems…it was time to end the strike,” union leader Karen Lewis said last evening, shortly after the vote to end the strike. And truly, the outcome of the strike could never have been to solve all the problems. Rather, its legacy should be a nationwide wake-up call to look closely at this broken system as well as realizing that a holistic approach may not be realistic and to begin the laborious process of fixing its manifold, interconnected parts.

Ilana Garon is a writer and teacher in New York City. Her work appears regularly in Dissent Magazine, Education Week, and Huffington Post.

Ilana Garon is a writer and teacher in New York City. Her work appears regularly in Dissent Magazine, Education Week, and Huffington Post.